But we could have done just fine without some of these relics. These rediscovered supposed treasures are so worthless that they collectively lowered humanity’s cultural credentials.

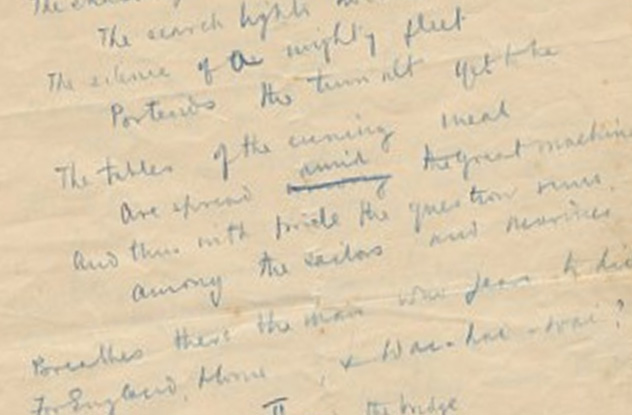

10Churchill’s Last Poem

In 2013, retired manuscript dealer Roy Davids seemingly made the find of a lifetime. Hidden among some useless papers was a 40-line work by Winston Churchill called “Our Modern Watchwords.” It had never before been published and represented the only known poem the Nobel Prize–winning author wrote as an adult. Unfortunately, it just wasn’t very good. The UK’s poet laureate Andrew Motion dismissed it as “heavy footed,” while the New Yorker’s poetry editor criticized it for using too many words. But the most damning indictment came when the poem was put up for auction. Despite Churchill memorabilia being so sought-after that his half-smoked cigars can fetch £4,500 ($7,100), the poem completely failed to sell. Instead, it was returned to Davis. It was the only auction item connected with Churchill that no one thought worth buying.

9Alfred Hitchcock’s Earliest Film

Our ancestors had quite a knack for losing important old films. Alfred Hitchcock’s first foray into feature-length cinema (as writer, editor, and assistant director), The White Shadow, vanished many decades ago. Thankfully for posterity, it was later recovered from a projectionist’s private collection in 2011 and restored. Unfortunately for posterity, we only found half of it. A five-reeler ghost story set in 1920s Paris, The White Shadow sets up an unbearably tense confrontation between a woman and her dead sister. By all accounts, it’s atmospheric, gripping, and superbly exciting . . . until the film cuts to black in the middle of an important scene. Somehow, over the decades, the final two reels had been lost. We’ll now never get to see how The White Shadow ended. It’s the worst of both worlds. We have the early parts, so we can see how brilliant it is, but we have none of the ending to give us closure.

8Doctor Who’s Missing Episodes

Like many old British series, Doctor Who has holes in its back catalog. Thanks to a BBC policy of wiping old tapes, the Doctor is now missing some 90-odd adventures from the ’60s. So valuable are these lost episodes that we get global news stories when any turn up, even if the episodes in question are unimaginably bad. In 2011, the BBC announced that they’d recovered part two of 1967 Patrick Troughton story “The Underwater Menace.” Almost immediately, Doctor Who fans worldwide went nuts. Then they actually saw the episode. Featuring a mad scientist who wants to turn people into dancing fish creatures, it’s since become famous as one of the worst episodes in the show’s 50-year history. The BBC’s own Doctor Who website quotes reviews that call it “tedious and cliched” and “The Doctor Who equivalent of Plan 9 from Outer Space.” Even worse for fans was knowing that it had been originally broadcast right after a highly sought story (“The Highlanders”), which many had been desperate to see returned. In the years since, the BBC has managed to recover nine more episodes from this period, all of which have been reviewed favorably. Yet “Underwater Menace 2” remains one episode that even the most hardcore Who fans would rather see returned to oblivion.

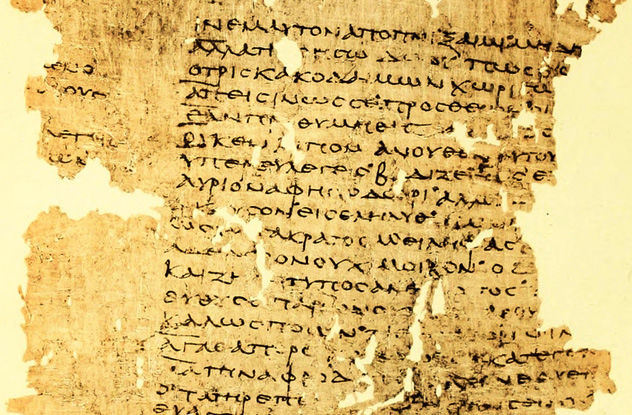

7The Library At Vesuvius

When Mount Vesuvius detonated in a cloud of boiling ash, it accidentally created one of the best-preserved historic sites on Earth. So immediate was the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum that everything in the two towns was buried in lava before it could disintegrate, including the library of statesman Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus. When the library was rediscovered in the 18th century, archaeologists found that its papyrus scrolls had carbonized. They were even readable, provided you could unwind them without destroying the contents, but this was near-impossible with contemporary technology. The find was still immensely exciting. As a politician at the height of Rome’s glory, Piso might have had works by Archimedes, Sappho, or Aristotle. The blackened scrolls were preserved for future generations to decipher. Then, in the late 20th century, we finally began uncovering their contents. Rather than unknown treasures of ancient literature, the scrolls contained nothing more than the dull treatises of a Greek philosopher hardly anyone had heard of. To make matters worse, the philosopher was a follower of Epicurus—a highly important ancient thinker with plenty of missing works that could have been preserved instead. Happily, however, the story doesn’t end there. The partially excavated library might contain other scrolls of significantly more importance. New techniques have already uncovered a section of a lost work by Epicurus, with possibly more to come.

6Michael Powell’s Missing Movie

Michael Powell is one of those directors other directors go nuts over. Martin Scorsese credits Powell with inspiring him to go into movies. Others have called his collaborations with Emeric Pressburger “uniquely brilliant.” So when the British Film Institute (BFI) recovered one of his lost early films in the late ’90s, people’s expectations were naturally high. The recovered film, His Lordship, got a withering review from London’s Time Out magazine, while the UK’s TV Guide laid into it with a level of venom bordering on the vindictive. Even the BFI itself admitted that it was flawed, although they also claimed it showed the scale of a young Powell’s ambitions. While there’s no doubting the film’s historic significance, it’s unlikely to ever become a classic in anyone’s book.

5Al Capone’s Secret Vault

In the late 1920s, Al Capone moved into the fifth floor of Chicago’s Lexington Hotel. At the time, Capone was the crime lord of the city, controlling the booze trade and nearly every other illegal venture. After his fall and demise, tales of his life in the Lexington became legendary. It was said that the building was stuffed full of money, guns, and even corpses. Capone’s associates had boasted they could empty the entire hotel in 15 minutes without ever setting foot in the street. It was even rumored that a secret vault, filled with treasures, was hidden under the old hotel. Then, in the mid-1980s, evidence of the secret vault began to emerge. Hidden stairways and tunnels were discovered in the empty Lexington. The whole of Chicago went into rumor overdrive. What if the vault was real? What impossible treasures might it hold? The answer: none whatsoever. When the vault was finally opened on live TV in 1986, a breathless nation got a big fat view of nothing. The vault turned out to simply be a concrete slab containing some Prohibition-era bottles and a whole lot of dirt. The TV special that broadcast the unveiling, The Mystery of Al Capone’s Vaults hosted by Geraldo Rivera, went down in history as one of the biggest washouts ever transmitted.

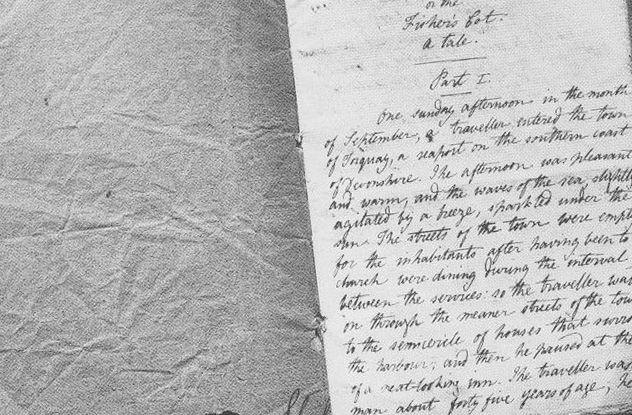

4Mary Shelley’s Children’s Story

Although most of us know her only for Frankenstein, Mary Shelley was incredibly prolific. In her lifetime, she published five novels, a travel journal, innumerable short stories, and a children’s book, Maurice, or the Fisher’s Cot. If you were unaware of that last one, don’t be ashamed: The story was considered lost for nearly two centuries. Then, in the 1990s, biographer Claire Tomalin rediscovered the manuscript in a tiny village in Italy. For the literary world, it was like getting hit by a lightning bolt. What impossible poetic treasures could be hiding in a new book by the author of Frankenstein? Although Maurice was far from being a total stinker, it was regarded at best as “slight” and at worst as both boring and flawed. Instead of repeating the moral complexities and gothic insights of Frankenstein, it offered up a dull slice of simplistic melodrama. It wasn’t even the sort of book that any child would willingly read, so it had value only to a handful of Shelley scholars.

3Phillip Larkin’s Lesbian Novels

Despite being the hermit librarian of a dull town in Britain, Phillip Larkin still managed to become one of the biggest poets of his generation. Mixing dour English cynicism with a good dollop of wit, the handful of works published in his lifetime were close to perfect. So when scholars discovered two previously lost novels in the Hull library years after Larkin’s death, people naturally paid attention. If Larkin could produce such breathtaking classics in only two pages, what could he do with 600? The answer: write a painfully embarrassing schoolgirl fantasy. Set entirely in a girl’s boarding school, Trouble at Willow Gables and Michaelmas Term at St Bride’s were dull school stories sprinkled with details of lesbian love affairs and occasional scenes of flagellation. Passages were devoted to the seduction of 14-year-olds, jammed in between a smattering of non-erotic sections best described as “purple.” The novels were so bad that they wound up detracting from Larkin’s phenomenal reputation.

2Van Gogh’s Lost Landscape

Unlike many of the items on our list, Sunset at Montmajour by Vincent Van Gogh was only ever lost in the sense that no one knew who had painted it. In the early 20th century, an art expert branded it a fake, and it spent the next 100 years derided as a poor imitation. Then, in 2013, the Van Gogh Museum—which had rejected the painting twice already—decided that it was the real deal. Sunset at Montmajour was unveiled at a lavish public ceremony. The only problem was it simply wasn’t very good. A banal-looking landscape, Sunset was perhaps one of the most disappointing rediscoveries in decades. The Guardian’s art critic called it an “uncharacteristic daub,” claiming that “if it vanished again tomorrow the world would not be much poorer.” The Los Angeles Times declared it “blandly pretty.” Even Van Gogh himself, in a letter sent to a friend in 1888, claimed the painting was “well below what [he’d] wished to do.” Although the painting has since been valued at over $40 million, the price tag has more to do with the name attached than with any artistic genius.

1The Plays Of Menander

For centuries, Menander was considered the greatest playwright who had ever lived. An Athenian dramatist who worked in the fourth century B.C., he was the Shakespeare of his time, a writer who could capture the drama of real life with uncanny skill. Critics called him the “supreme poet.” St. Paul quoted him in the Bible. When his last known manuscript vanished in the 16th century, it was considered a gigantic blow to mankind. Goethe publicly lamented his lost genius. People compared him to Moliere and Cervantes. Then we got him back. In 1905, a bundle of Menander’s plays were discovered in Cairo. Nearly 50 years later, they were finally deciphered and broadcast by the BBC. They were awful. His supposed real-life plots tended to involve sentimental orphans discovering that their foster parents were secretly their real parents and living happily ever after. The comic plays usually involved someone raping a stranger or committing incest. At best, critics called the plays “remarkably unambitious.” At worst, they were hack work of the highest order. As writer and critic Stuart Kelly noted, “Lost, Menander was a genius; found, he was an embarrassment.”