As the number of legendary locales grew over the centuries, so did the number of explorers bent on finding them. Many were tantalized by visions of gold, jewels, and various treasures, while others wanted to cement their names in the pantheon of history. Some sought powers beyond human comprehension or a pathway to a paradise that seemed all too good to be true. And yet others simply had an insatiable curiosity for solving a mystery that had vexed their contemporaries. While all of these things proved to be strong motivators for some, they also proved to be deadly. While many real people have sought out these whimsical worlds, more than a few have lost their lives, either directly or indirectly, as a result.

10 Diego De Ordaz

Diego de Ordaz was a Spanish explorer and soldier born around 1480. He participated in Hernan Cortes’s conquest of the Mexican mainland and was recognized for his contributions to several critical military incursions, including a victory over the Aztecs at the Battle of Centla in 1519. He became especially well-known for his toughness and ascended through the ranks after becoming the first European, along with two compadres, to scale the 5,426-meter (17,802 ft) Popocatepetl (the second highest volcano in Mexico). Emperor Charles V granted Ordaz permission to use a coat of arms emblazoned with the volcano in 1525, during which time he returned to the Americas and eventually became governor of Paria in the eastern region of Venezuela. In the late 1520s, explorers commissioned by the German Welser banking family began embarking on expeditions into Venezuela’s interior in search of a mysterious city laden with gold. (The city would later be dubbed El Dorado by the Spanish.) Hearing of this, Ordaz got permission to begin his own exploration of the monstrous Orinoco River in 1531 in hopes of finding the land of riches. He managed to travel beyond the mouth of the Meta River but unfortunately was forced to turn back after the rapids at Atures proved too much to overcome. On his return home in 1532, he came into conflict with the governor of Trinidad, was imprisoned, and died shortly after, possibly due to poisoning.[2]

9 Philipp Von Hutten

Philipp von Hutten, born in 1505, was a German adventurer and significant figure during the mid-16th century colonization of the Americas. From 1528 to 1546, Charles V granted the Welsers concession of the Venezuela province, which the Germans called Klein-Venedig. As chatter of El Dorado[3] hit a fever pitch in the 1530s, von Hutten joined with a troop of more than 600 explorers under the command of Georg von Speyer to find the hidden treasure somewhere deep in the jungle. Their long, arduous journeys between 1535 and 1538 eventually led them to the headwaters of the Japura River close to the equator, but they found no treasure. Von Speyer died in 1540, and von Hutten was subsequently promoted to captain-general of Venezuela. He continued his search in August 1541, departing from the city of Coro and crossing the Rio Bermejo with a small band of horsemen. He soon encountered a large contingent of Omagua natives, engaged in battle with them, and was seriously wounded. He and the few who survived, including banking family magnate Bartholomeus VI. Welser, weak from hunger, sickness and war wounds, returned to Coro, only to be captured and beheaded by Spanish conquistador Juan de Carvajal, leading to the eventual withdrawal of the Welsers’ colonial rights.

8 Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English writer, poet, soldier, and explorer, not to mention perhaps one of history’s most famous treasure hunters. He was born to a Protestant family in 1552 in England, began his voyages to the New World in 1578, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1585. By 1594, word had reached him of an elusive “City of Gold” somewhere in South America. In 1595, he set off with collaborator Antonio de Berrio in search of the equally mythical Lake Parime in the highlands of Guiana, the alleged location of El Dorado during this time (which Raleigh believed was actually a city called Manoa). He came up empty. In March 1603, Queen Elizabeth died, and by July, Raleigh was arrested for conspiring against her successor, James I. He spent the next 13 years imprisoned in the Tower of London but was released in 1616 and allowed to return to Guiana for a second attempt at finding Manoa, this time bringing along his son, Walt, and longtime friend Lawrence Keymis. However, early on in the journey, Keymis ordered his men to attack a Spanish outpost in defiance of Raleigh’s orders, resulting in Walt’s death and causing a distraught Raleigh to head back to England. The Spanish ambassador demanded Raleigh be executed for violating their countries’ peace treaty, and as a result, a fed-up King James finally obliged in October 1618.[4]

7 Juan Ponce De Leon

Juan Ponce de Leon was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who has long been associated with his quest for the legendary Fountain of Youth. Born in 1474, he first came to the Americas at the age of 19 on Christopher Columbus’s second expedition. He was a quick study in military and political matters, becoming a top regional official by his late twenties, when he quashed a tribal rebellion on Hispaniola. He was given authorization to explore the nearby island of Puerto Rico in 1508 and was subsequently named its first governor. In 1513, he set out for further exploration, reaching the coast of Florida. Rumor has it that the mysterious life-giving fountain, which Europeans had been whispering about long before Ponce de Leon, served as the impetus for his trip. However, most historians note that such an account wasn’t given until after his death in 1521—the first occurring in Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes’s Historia general y natural de las Indias in 1535, which claimed he was seeking a cure to his sexual impotence through the mystical “waters of Bimini.”[5] Author Arne Molander posits he may have been seeking the Bahamian love vine—brewed as an aphrodisiac—for both personal and commercial purposes but misinterpreted the natives’ use of vid (“vine”) for vida (“life”). On his final trip to Florida in 1521, Ponce de Leon and his followers were attacked by Calusa warriors, and he was killed when a poison-tipped arrow struck his thigh.

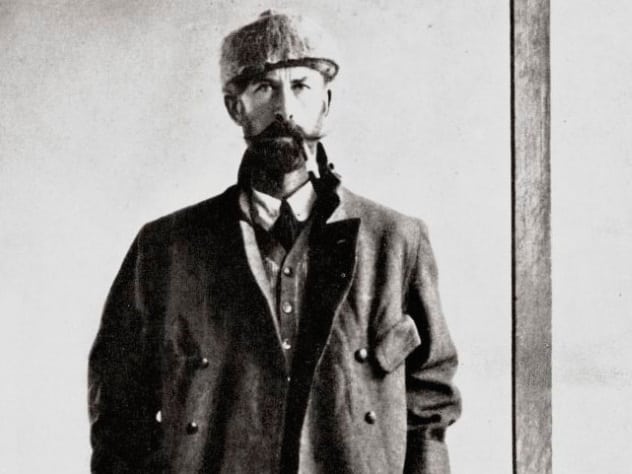

6 Percy Fawcett

Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett was a British surveyor, archaeologist, geographer and cartographer who has served as the inspiration for many of Hollywood’s most famous adventurers, including Indiana Jones. He joined the Royal Geographical Society in 1901 to study the craft of mapmaking and was later employed by the British Secret Service in North Africa. His first expedition to South America in 1906 was to map a jungle at the border of Bolivia and Brazil for the RGS, with six more expeditions to follow between then and 1924.[6] By 1914, Fawcett had begun to formulate ideas, based on his research, about a legendary lost city he named “Z.” In 1925, he led a three-man team that included his son Jack and Jack’s longtime friend Raleigh Rimell into the uncharted Mato Grasso jungle region of Brazil to find the Lost City of Z. Unfortunately, the trio mysteriously disappeared and were never seen again. Even more eerily, about 100 people have died or vanished looking for them in the following decades. It’s been speculated that Fawcett’s city was inspired by the legends of Kuhikugu, a widespread archaeological site discovered in the early 21st century that spanned 19,900 square kilometers (7,700 mi2) and once had over 50,000 inhabitants.

5 Francisco Vazquez de Coronado

Born in 1510, Francisco Vazquez de Coronado was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who became governor of New Galicia, a Spanish province in Northwestern Mexico, by the time he was in his late twenties. It was during this time that he started hearing tales about the “Seven Golden Cities of Cibola,” which were supposedly situated to the north along the Pacific Ocean and had streets paved with gold. In 1540, he organized an extremely costly expedition, composed of hundreds of Spaniards and indigenous peoples, through much of North America’s uncharted terrain. It would be split into both land and sea units.[7] Between 1540 and 1542, Coronado trekked from Mexico up through modern-day Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Kansas. In June 1540, he came across what he thought was the first city of Cibola. However, it turned out to be a remote Zuni pueblo town called Hawikuh, whose population resisted Coronado’s attempt to subdue them. He continued on through the spring of 1541, finding only outlying indigenous villages rather than cities of gold. When he returned to Mexico, he was smeared with charges of incompetence and was forced into bankruptcy. He finally died in 1554 of an infectious disease, scarred and broken from his ill-conceived quest. However, despite all this, Coronado and his men are credited with being the first Europeans to discover both the Grand Canyon and the mouth of the Colorado River.

4 Admiral Richard E. Byrd

United States naval officer Richard E. Byrd Byrd was a world-class explorer and aviation pioneer who led expeditions across the Atlantic Ocean, Arctic Ocean, and Antarctic Plateau. He served during World War I, training as a pilot in 1917 before being promoted to lieutenant a year later. During this time, he developed a real passion for flying and is credited with several techniques that changed the course of aerial navigation. In 1926, he was the first to fly over the North Pole and returned home a hero, where he was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Calvin Coolidge and promoted to the rank of commander. Later, Byrd would go on to lead three expeditions to the South Pole—in 1928, 1934 and 1939—demonstrating an uncanny fascination with the ends of the Earth.[8] In the 1960s, Dr. Raymond Bernard wrote a bizarre book called The Hollow Earth that claimed the poles actually served as entrances to a subterranean realm filled with undiscovered continents and inhabitants. He buttressed this claim with facts about how the poles get warmer than areas up to 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) away and how tropical birds fly north in the wintertime. Moreover, he and his fellow theosophists say that Byrd searched for and perhaps found the entrance to Hollow Earth but died shortly after from congestive heart failure induced by cold temperatures. While most historians have chalked this up to conspiracy gobbledygook, the book’s longevity shows that some may believe in Byrd’s ulterior motives.

3 The Naxi People

The Naxi (also known as Nakhi or Nashi) are an ethnic group living in the Himalayan foothills of China’s Yunnan province. Looming over the province is the 5,596-meter (18,360 ft) Yulong Snow Mountain (or Jade Dragon Snow Mountain), whose massif forms much of the larger Yulong Mountains to the north. A cable car takes tourists 4,506 meters (14,784 ft) above sea level, where they’re treated to an expansive view of the surrounding terrain. Somewhere in the nooks and crannies of this rippling landscape is alleged to be hidden the secret paradise of Shangri-La, first described in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton. However, ancient Buddhist scriptures have long mentioned similar hidden lands, such as the seven secret cities known as the Nghe-Beyul Khembalung. Not surprisingly, the Naxi have their own traditional lure about how to find Shangri-La. According to legend, young couples who commit suicide by jumping from Yulong Snow Mountain will enter Shangri-La and receive eternal happiness.[9] And apparently, many over the decades have met their fate trying. News reports as recent as 2015 have people riding the cable car up the mountain only to jump to their deaths.

2 Robert Restall

Robert Restall was an excavator lured to Nova Scotia’s enigmatic Oak Island in 1959 after hearing about a legendary pirate’s treasure buried there. Other stories claimed that the island held Marie Antoinette’s jewels, original Shakespearean manuscripts, and rare religious artifacts. These items were allegedly placed in a series of booby-trapped tunnels that were built over sinkholes and were meant to flood if tampered with. Two men from earlier excavations had already died searching for the legendary tunnels; one was severely burned when a water pump boiler machine exploded, and the other fell to his death when a rope slipped off a pulley. Undeterred by the portentous past events, Restall signed a contract with the property owner to excavate and arrived shortly after with his partner Karle Graeser, his teenage son, and his team. On August 17, 1965, he was working to seal a storm drain when a faulty engine on a piece of equipment began filling the shaft with poisonous hydrogen sulfide fumes, knocking him out. Robert’s son tried to save him but lost consciousness as well. Graeser and two other workers went down to rescue them, but only one of the workers came out alive. Restall, his son, his partner, and the other worker all died.[10] Local legend has it that seven people must die before the Oak Island treasure will be revealed. Restall and his team made six. No one else has died there since.

1 Adolph Ruth

Adolph Ruth was an East Coast veterinarian with the US Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Animal Husbandry and an amateur explorer who was obsessed with locating the storied Lost Dutchman Mine, holding 19th-century prospector Jacob Waltz’s hidden riches. Through his son, Edwin, Ruth had gotten hold of some maps that seemed to indicate the location of the mine was in the Borrego Desert area of San Diego County. In 1914, father and son headed out to California looking for the loot but came up empty-handed. They returned five years later but found only tragedy as Ruth fell from a steep ravine, fracturing his thighbone, which resulted in a permanent limp.[11] However, an 1895 San Francisco Chronicle article titled “One of Arizona’s Lost El Dorados” and the lucky discovery of an unnoticed map led Ruth in a new direction: the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, just east of Phoenix. He set off alone in 1931 with the new map but subsequently vanished without a trace. The following winter, his body was found with two bullet holes to the skull, and local authorities speculated that he was murdered for the map, which was not on him. Ruth may be the most famous man to die looking for the Lost Dutchman Mine, but some sources say more than 500 explorers have joined his fate, including, most recently, Denver treasure hunter Jesse Capen, who disappeared in Tonto National Forest in 2009, only to have his remains found three years later at the bottom of a chasm. Mark Heidelberger has been writing for over 22 years and has had more than 1,200 articles published online since 2009. He has written for a variety of well-known publications, including USA Today, AZ Central, LA Examiner, Houston Chronicle‘s Chron.com, Hotels.com, Trails, Leaf Group, Bolde Media, and Aliyah Media. He previously studied creative writing at both UC Santa Barbara and UCLA.