But, as the axiom goes, “truth is stranger than fiction.” Throughout history, real-life detectives have performed amazing feats of sleuthing that rival any fictional exploits. These 10 gumshoes dazzled the general public with their abilities and larger-than-life personalities, and they were also involved in some of the most historically important cases of their respective eras.

10 Izzy Einstein And Moe Smith

Isidor “Izzy” Einstein and Moe Smith were two middle-aged men from New York’s Lower East Side who managed to arrest 4,932 offenders, haul in roughly five million bottles of illegal liquor, and sport a conviction rate of 95 percent from 1920–25. Before becoming the premier booze detectives of their day, the Austrian immigrant Einstein had been a street peddler and a postal clerk, while Smith had owned a cigar store. When the duo first applied to work for the Prohibition Bureau for $40 a week, the G-men in charge weren’t overly impressed. Somehow, Einstein and Smith managed to convince their superiors by selling them on the idea that hoodlums would never suspect two portly, regular-looking guys of being undercover agents. Einstein and Smith, like Sherlock Holmes before them, gained a reputation for being excellent at concocting disguises that actually worked. Sometimes, the pair got away with hiding in plain sight, even though most speakeasies had their pictures hanging on the wall. Ultimately, it wasn’t the criminals who sank the careers of Izzy and Moe, but their own fellow agents, who grew increasingly jealous of the pair’s success. Unlike fictional detectives, Einstein and Smith weren’t neurotic geniuses who relied on their vast wealth of knowledge. For the most part, the pair became successful detectives because of their willingness to work long hours and their native knowledge of New York City life. Einstein was also gifted with languages—when need be, he could converse with suspects and witnesses in Yiddish, German, Polish, Hungarian, and even Chinese.

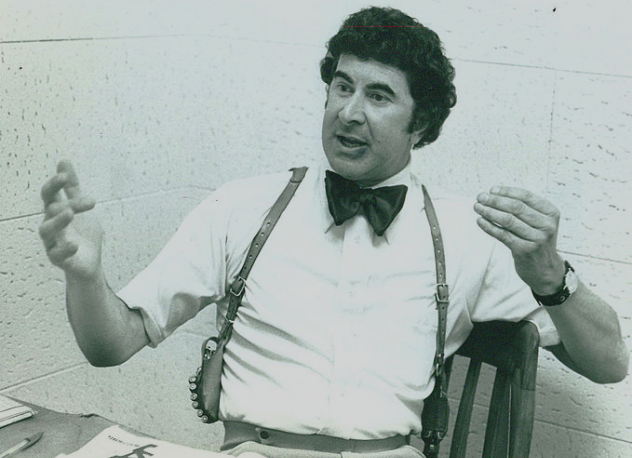

9 Dave Toschi

When your name gets mentioned as the possible inspiration behind both Inspector Harry Callahan of Dirty Harry fame and Steve McQueen’s turn as Lieutenant Frank Bullitt in 1968’s Bullitt, you know you’re cool. The man who can make that claim is Dave Toschi, who served as an inspector in the San Francisco Police Department from 1952–83. During Toschi’s time in San Francisco, he was known for dressing well, being meticulous, wearing his gun in a trademark quick-draw holster, and constantly munching on animal crackers. He was also known as one of the primary detectives involved in the still-unsolved Zodiac case. From December 1968 until October 1969, the Zodiac Killer terrorized San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area with a string of grisly murders. Worse still, the killer taunted and tormented the police and public alike with bizarre letters or ciphers and several threats concerning acts of terrorism that would target schoolchildren. For his part, Toschi, along with other members of the San Francisco PD, relentlessly hunted the killer for years, although their efforts were never rewarded with a conviction. The closest Toschi came to catching Zodiac was the investigation of Arthur Leigh Allen, whom Toschi has called “the best suspect” in the entire case. While Toschi is mostly famous for his role in the Zodiac case , he was also involved in investigating the Zebra murders, a series of racially motivated murders and attacks committed by a black nationalist gang against random whites during the mid-1970s.

8 Johnny Broderick

Often called the “Broadway Cop,” Johnny Broderick patrolled New York’s theater district as a member of the New York Police Department from 1923–47. In his time, Broderick was known throughout the city as a cop not to be messed with. His reputation was mostly built around his willingness to beat up gangsters and suspects alike, and many stories about “Broadway Johnny” portray him as a larger-than-life tough guy who could easily lick the hard-boiled detectives created by writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Born into an Irish-American family in Manhattan’s Gashouse District, Broderick came home after serving in the Navy during World War I and became a “labor slugger.” He also served as the bodyguard for Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor. Then, after a brief turn as a firefighter, Broderick became a patrolman in 1923. During his time on the force, Broderick beat up the legendary New York gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond and dumped him into a garbage can, and he also performed bodyguard work for the heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey. Besides his beating of “Legs” Diamond, Broderick was also famous for squaring off against armed prisoners in New York’s infamous Manhattan Detention Complex, better known as The Tombs. When the prisoners barricaded themselves behind a coal pile in a last-ditch effort to fend off a police counterattack, Broderick rushed them and began firing at the would-be escapees. Broderick’s brazen attack may have been the thing that finally drove the criminals to commit suicide. Although loved by a large portion of the New York public for his willingness to tackle crime head-on, Broderick was loathed by many politicians and was the frequent target of civil cases that accused him of misconduct and police brutality.

7 William J. Burns

Called “America’s Sherlock Holmes” by no less of an authority than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself, William J. Burns managed to go from being the son of an Irish immigrant in Columbus, Ohio, to the one-time director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI). Burns mostly made a name for himself as a private detective, however, and while running the William J. Burns International Detective Agency, he took the lead in investigating some of the most widely covered crimes of the early 20th century. In 1910, Burns was hired as one of the lead investigators in charge of solving the deadly bombing of the Los Angeles Times building. An early example of domestic terrorism, the bombing killed 20 people in the name of a workers’ revolution. A year later, Burns and his men arrested the dynamiters, John J. and James B. McNamara, after following a trail of dynamite from the Midwest to Los Angeles. Less than a decade later, Burns was again involved in another case of domestic terrorism. In 1920, a powerful bomb ripped through Wall Street, killing 38 and wounding around 400. Burns was soon on the scene and was an early supporter of the idea that the attack had been carried out by Communist sympathizers. The Wall Street Bombing case would prove to be a dead end though, and as of today it is still unsolved. Burns’s next move would prove even more disastrous, for not long after accepting the role of Director of the BOI, Burns became embroiled in numerous scandals, one of which saw Burns using his agents to discredit Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana. At the time, Wheeler was the head of the Senate committee looking into the Teapot Dome Scandal, which involved members of the Harding Administration leasing oil-rich government land to private companies. It’s likely that Burns was told to gather dirt on Wheeler by members of President Harding’s inner circle. After Burns’s role in the whole affair came to light, he was forced to resign from the BOI. He spent the rest of his life writing detective stories in Florida, while he watched as his replacement, J. Edgar Hoover, thoroughly modernized the BOI into the new FBI.

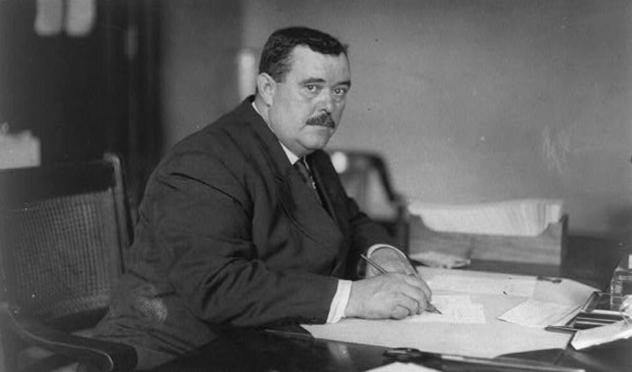

6 William J. Flynn

William J. Flynn and William J. Burns were contemporaries who not only shared the same first name and middle initial, but also the same look. Both men were powerfully built, with large stomachs and well-trimmed mustaches that made them both resemble President Theodore Roosevelt. In another twist of fate, both men began their law enforcement careers in the United States Secret Service under President Roosevelt, worked as private investigators, and headed the Bureau of Investigation, with Flynn serving from 1919–21 and Burns serving from 1921–24. Where the two diverge, however, is significant. Unlike Burns, Flynn spent some years as a professional lawman working for New York City. While working as a deputy commissioner for the NYPD, Flynn helped to reorganize the Detective Bureau along the lines of Scotland Yard and the Secret Service. Flynn also battled the first incarnations of the American Mafia , which at that time was ruled by the fearsome Giuseppe Morello. In 1910, Flynn and other members of the Secret Service office in New York were responsible for putting together the case that led to Morello being convicted of counterfeiting. Later, during World War I, Flynn worked as the chief of the United States Railroad Secret Service, a job which put him in direct contact with would-be saboteurs. Flynn would face some of these saboteurs again in 1919, when, as a noted expert on anarchists, he was called in by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer in order to execute the so-called “Palmer Raids,” which helped to touch off the First Red Scare.

5 Ellis Parker

Like William J. Burns, Ellis Parker was also known as “America’s Sherlock Holmes.” But, unlike both Burns and Holmes, Parker did not serve in order to protect a nation or a major city. For 44 years, Parker was the Chief of Detectives of Burlington County, New Jersey, a mostly rural county in the Delaware Valley. One would think that life as a small-town detective would be far from exciting, but during his career, Parker investigated some 300 crimes, many of which were characterized in the local press as almost unsolvable mysteries. Initially a national celebrity, Parker became a reviled figure during the Lindbergh kidnapping case for kidnapping and torturing an innocent suspect, a crime that caused him to spend several years in a federal penitentiary. Worse still, the man Parker suspected of actually committing the heinous kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son was his own partner, Trenton attorney Paul Wendel. The fact that the execution of Bruno Hauptmann, the man convicted of the murder of Charles Lindbergh Jr., was put on hold for 48 hours because of Parker’s accusations against Wendel is proof enough of his widespread respect as an investigator. Before being disgraced in 1936, Parker was known throughout the United States as a brilliant, yet homespun, detective who often received letters asking for advice from other professional lawmen. One case in particular, the so-called “Case of the Pickled Corpse,” is still held up today as a masterstroke of deduction, early forensics, and meticulous detective work. The case began on October 5, 1920, when William (some sources say David) Paul, a bank messenger for the Broadway Trust Bank in Camden, New Jersey, left for the Girard National Bank in Philadelphia with $42,000 in checks and $40,000 in cash and never returned. Eleven days later, Paul’s corpse was found in a shallow grave in Burlington County by duck hunters. The body still had $42,000 in checks, but all of the cash had been stolen. As it turned out, Paul had been killed by two men, Frank James and Ray Shuck, who had been Paul’s friends and fellow partiers at the Lollipop Inn, a bungalow owned by James. After murdering Paul in order to rob him, the pair then tossed his body into a stream in a remote area. Parker, who found a pair of eyeglasses belonging to James at the crime scene, also noted that Paul’s body had been found downstream from a tanning factory, which meant that Paul’s body had been submerged in water that contained a high amount of tannic acid, a strong preservative, for days. Hence, Paul’s corpse had been “pickled.” When Parker presented this evidence to James, the latter broke down and confessed.

4 Marcel Guillaume

It’s not certain, but many believe that Georges Simenon based his prolific Inspector Jules Maigret on the French detective Marcel Guillaume. Originally born in the French provinces, Guillaume moved to Paris and was urged to become a police officer by his father-in-law, who was a policeman himself. For decades, Guillaume honed his skills and became known for being an able and patient investigator who knew the streets of Paris better than almost anyone. One of Guillaume’s most famous cases came in 1933, when Violette Noziere, an 18-year-old from a middle-class family, poisoned her parents with drinks laced with an excessive amount of barbiturates. The father died, but the mother managed to survive. Violette’s next moves only confirmed her guilt, as she first went on a shopping spree with money stolen from her parents and then tried to leave the country. Before long, Violette offered a full confession, which turned an ordinary murder case into a sensation. According to Violette’s initial confession (she would go on to make many more), she had committed the murder in order to gain revenge after years of being raped by her father. Guillaume’s role in the Noziere case began immediately after the body of Jean-Baptiste Noziere was found. While searching the crime scene with other detectives, Guillaume learned that Violette had been forging notes under the name of Dr. Deron. In the notes, Violette, who was herself being treated for anemia, recommended that her parents begin taking unspecified powders for their health. Of course, Violette jumped at the opportunity to play nurse for her parents, and the murder plan was put into action. During the trial, it was conclusively proven that Violette had poisoned her parents and left them to die in order to establish an alibi. Violette’s promiscuousness, which Guillaume helped to establish, and her accusations against her father made her reviled among a large segment of the French press, while some, like the Surrealists, actually viewed her crime as an expression of both art and resistance against what they saw as repressive French society. Before and after the Noziere investigation, Guillaume worked on some of the most high-profile cases in French history. He was involved in investigating the crimes of serial killer Henri Landru, as well as the financial manipulations of Alexandre Stavisky. The Stavisky Affair in particular pitted Guillaume and his men against the powerful movers and shakers in French politics during the interwar years.

3 Ignatius Pollaky

Commonly known as “Paddington Pollaky,” Ignatius Pollaky was a Hungarian immigrant who became one of Victorian England’s first and most popular private detectives. In 1881, Pollaky was preserved for posterity when his name was used in a song for the Gilbert and Sullivan play Patience. Prior to becoming a piece of theater history, Pollaky had operated a “private inquiry office” (a precursor to today’s private detective agency) and was known for hobnobbing with the likes of the novelist Charles Dickens and Jack Whicher, a famous detective in his own right. Pollaky developed a reputation as a dazzling investigator during the 1860s–70s. He was frequently consulted by Scotland Yard whenever a case involved criminals from the Continent. Pollaky’s ability to speak six languages, along with his deep interest in the inner workings of the criminal mind, made him a formidable detective. Pollaky was also an enigmatic personality, and at the height of his celebrity in the 1880s, he retired from detective work. Of all the cases that Pollaky ever investigated, the most famous was the 1860 Road House murder, which is the focal point of Kate Summerscale’s celebrated book, The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher. Although Summerscale’s book predominately focuses on Inspector Jack Whicher, the appendix does note that Pollaky was present during at least one official examination. Furthermore, it was noted at the time that Pollaky stayed at an inn in the area during the investigation, and he would frequently be on-hand at the Kent house in order to take notes. Who knows? Maybe Pollaky was the first to see that the four-year-old Francis “Saville” Kent had been murdered by someone from within the family.

2 William E. Fairbairn

Between the World Wars, Shanghai, China, was one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Divided into sections that separated the native Chinese from Europeans, Shanghai was home to a robust smuggling trade and several red-light districts that not only sold women, but also drugs and guns. Enter William E. Fairbairn. Originally born in England, Fairbairn immigrated to Shanghai after serving in the British Royal Marines. Not long after setting foot on Chinese soil, Fairbairn enlisted with the Shanghai Municipal Police. Fairbairn quickly learned that walking a beat in Shanghai as a patrolman or plainclothes detective was akin to serving in a war zone, and by his own account, he was involved in some 600 combat situations with Shanghainese criminals. In order to combat this lawlessness, Fairbairn, as the head of the SMP from 1927–40, organized one of the world’s first SWAT teams and also developed Defendu, a close-quarters combat fighting system that taught officers how to block and parry knife thrusts and other potentially deadly attacks. During World War II, Fairbairn was recruited by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service and soon began training British commandos in the ways of Defendu. Also, Fairbairn, along with Eric Sykes, developed the Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife (pictured above), a dagger that was quickly adopted by British commandos and members of the American OSS for use in World War II. Besides sporting the awesome nickname of “Dangerous Dan,” Fairbairn has also been mentioned as a possible inspiration for the character of Q in Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels.

1 Raymond C. Schindler

Raymond C. Schindler’s early life was neither thrilling nor indicative of his later life as a famous detective. Born in the tiny northern New York town of Mexico, Schindler would go on to attend high school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, before becoming an insurance agent, a typewriter salesman, and a gold miner in California. After answering an advertisement looking for college graduates interested in doing historical research, Schindler found himself, at age 25, working alongside the San Francisco Police Department as they pursued a graft case involving high-ranking politicians. While in San Francisco, Schindler met a Secret Service agent named William J. Burns and became the older detective’s protege. By the 1910s, Schindler was the head of the New York–based Schindler National Detective Agency (also known as the Schindler Bureau of Investigation) and was well-known across the country as a brilliant private investigator. Much of Schindler’s success was based on his use of the latest technologies at the time, one of which included the dictograph. For a while, Schindler had exclusive rights to the dictograph, a type of recording device that he used in multiple cases. Not long after his death in 1959, Schindler’s name was already synonymous with greatness in the field of detection. There was one case that Schindler could not solve, however. In 1943, Sir Harry Oakes, a wealthy introvert from Maine who had made his money in Canada as a gold prospector and mine operator, was murdered. Oakes’s body was found beaten to death in his Bahamian mansion. The culprits had tried to burn Oakes’s body but only managed to scorch it. Oakes’s mansion, too, was saved from an all-consuming fire. Amazingly, despite the involvement of the local CID and the Duke of Windsor (who was then the governor of the Bahamas), Oakes’s murder remains unsolved. At the time, Schindler was hired to investigate the case for $300 per day plus expenses, but even with such a generous salary, Schindler failed to wrap up this wartime mystery. Schindler’s inability to solve Sir Harry Oakes’s murder did not diminish his reputation, and in 1952, the Goodyear Playhouse produced the television movie Raymond Schindler, Case One, which starred a young Rod Steiger. Benjamin Welton is a freelance journalist based in New England. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, VICE, Crime Magazine, and others. He currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogspot.com. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet