10 Jawbone Jewelry

Wearing a late family member’s bones and calling it bling will lose anybody serious social points. Around 1,300 years ago, however, the opposite may have been the case. In Mexico, families occupied a residential site in the Oaxaca Valley called Dainzu-Macuilxochitl for nearly four centuries. They were the Zapotecs, and they still exist in the region. A ceremonial quarter was found in 2015 and contained human jawbones as well as ceramic figurines and whistles. The entire clay collection had been purposely smashed, but the skeletal remains were lovingly carved and painted. Even though some of the figurines depict the god Xipe Totec, a deity linked with human sacrifice, archaeologists believe that the jawbones weren’t from sacrificial victims. Instead, to solidify their right to be a part of the community, descendants showed their connection to earlier generations by digging them up and picking a piece to wear. Xipe Totec is sometimes shown with necklaces made of human bones, making it likely that the Zapotecs also wore their ancestors’ remains like neck jewelry.

9 Oldest Dentures

Italian archaeologists tend to hang around the San Francesco convent in Lucca. Over 200 ancient skeletons already held their interest, but in 2016, one family tomb delivered the oldest dentures ever discovered. Consisting of five incisors and canines, the real human teeth likely originated from the mouths of different people. The somewhat gross device wasn’t an uncommon one for the Romans. Both the Romans and Etruscans created false pearly whites from the teeth of animals and humans as far back as 7 BC. There are texts from the 14th to 17th centuries that describe dentures, but the San Francesco artifact is the first to surface from that era, making it the historical star of dentistry. The snappers were held together by a band of gold that also fit them to the lower gums of the user. Tests showed that the coating on the teeth contained gold, silver, and other metals. Tartar buildup proved that the device was used for a long time.

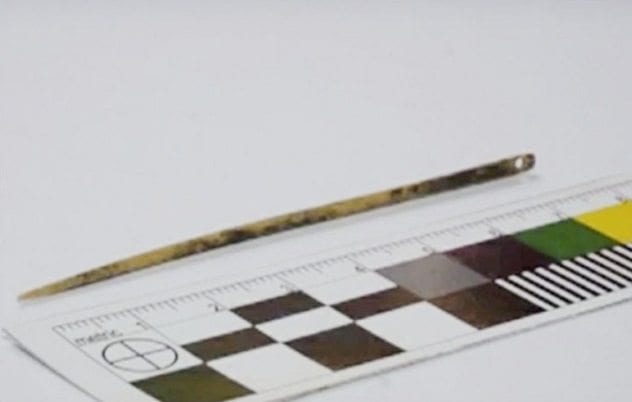

8 The Denisova Needle

A 50,000-year-old needle stunned scientists during an annual dig at Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. The site is already famous for “X woman,” who only left behind a finger bone but alerted researchers to the existence of a new hominid species in 2008. Long extinct, they were called Denisovans, after the cave. Found in 2016, the 7-cetimeter (2.8 in) needle is the longest to come from the site and the oldest in the world. A Denisovan hand-crafted the tool from an unidentified bird’s bone and even shaped it with an opening for thread. The needle supports previous finds suggesting that the Denisovans were technologically superior to Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Found in the cave the same year as “X woman” was chlorite bracelet. Shaped and polished some 10,000 years after the needle, it’s remarkably modern, but what dropped jaws was a hole in the jewelry piece. Scientists determined that it was drilled with a precision tool, much like the high-rotation drills of today.

7 Disposable Cups

Throwaway ceramics were the vogue trend of 15th-century German elites. When archaeologists dug in the courtyard of Germany’s Schloss Wittenberg, they didn’t find the shards of a few cups; they found thousands of broken drinking vessels. The porcelain cups were richly decorated with stamps and mask-like images. To throw one of these over your shoulder after guzzling the contents was seen as a sign of affluence enjoyed only by the nobility. Together with the disposable mugs, a lot of wild animal bones were found. Clearly, the feasts held in the courtyard included a lot of drinking and gorging on large quantities of venison. Sweeping up the next morning didn’t appear to be a priority, as layers of smashed porcelain and bones were found. Held in the summer, the courtyard parties continued for many years, the cups featuring as an exclusive item created especially for the event.

6 Bear Cub Rattle

One particular baby was much-loved during Bronze Age Siberia. He or she received a clay rattle shaped to resemble a young bear’s head. The cute cub still rattles, and future X-rays will determine what exactly causes the sound. Experts are guessing that the maker added small stones before sealing the beautiful toy. It was found in 2016, inside one of the homes at an archaeological complex where an ancient community once lived in the Novosibirsk region. The 4,000-year-old rattle was created by hardening clay with fire and attaching a handle big enough for a child to grasp. The artisan also added a squiggle to the clay while the object was still drying, which archaeologists suspect could have served as some sort of personal signature. What’s being called the “find of the year” by Novosibirsk experts is also one of the world’s oldest playthings.

5 Disaster Eggs

One of Turkey’s ancient cities, Sardis was gripped by an earthquake in AD 17. The damage took decades to rebuild, and until now, there has been no indication of how it affected the citizens on a personal level. In 2013, an excavation at a reconstructed building revealed how the locals might have coped. Beneath the floor were two boxes, each containing identical items: tiny bronze tools, a coin, and an eggshell. The people of Sardis lived during a time when eggs could both protect and curse a person. The coins date to AD 54–68, some time after the disaster, and one bears the image of a lion, which may represent the mountain and storm goddess Cybele. As the deity of these elements, she’d be the perfect protector from future earthquakes. What makes this discovery so heartfelt is that it appears to have been an individual’s way of dealing with uncertainty. The ritual was likely an attempt to protect the new building and its occupants from curses and natural disasters.

4 Ancient Cream

Two millennia ago, a Roman man or woman closed their cream pot, and it remained unopened until 2003. The pot was unearthed at Tabard Square, a temple complex in London dating back to around AD 50. The round artifact, 6 centimeters (2.4 in) in diameter, was remarkable for its quality and waterproof lid. The pot was made almost entirely of tin, a precious metal during Roman times, indicating that it belonged to someone in the uppermost crust of Roman society. The pot was already unique for being a sealed container, and when archaeologists pried off the top, it became even more so. Inside was a white ointment smelling of sulfur. Usually, only the containers of ancient cosmetics survive, not their contents. In this case, the paste inside was pristine. The pot had one final surprise. When researchers looked under the lid, they found the owner’s fingerprints in the cream. Further testing will determine the nature of the paste.

3 Down The Drain

Researchers have found a unique way to study the Romans: plumbing their bath drains. What sounds like a mucky job has retrieved long-lost details about what visitors did while relaxing at these social centers. Findings ranged from the expected to the highly surprising. Bath ruins from five European countries were examined, all from the first to fourth centuries AD. What the Romans did while sitting in the water varied incredibly. Apart from things associated with bathing (perfume and oil vials, tweezers), a scalpel and teeth indicated medical procedures, and dice and coins betrayed some gambling. Oodles of jewelry showed that Romans took off their clothes but not their valuables. Aquatic meals led to lost pieces of cups and bowls down the drains. The plungers brought up mussels, shellfish, poppy seeds, venison, goat meat, pork, mutton, beef, and fowl. Unexpectedly, needles and partial spindles popped up. Not really a water sport, needlework most likely happened in the non-bathing areas. How those items ended up in the gutter is not clear.

2 Pocket Sundial

Pompeii’s neighbor, Herculaneum, also perished when Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD 79. In the 1760s, workers clearing volcanic debris from the Villa dei Papiri pulled an odd metal object from the ruins. It was identified as a pocket sundial and earned the moniker “pork clock” because it was shaped like a hanging ham. Recently, a plastic replica was made using a 3-D printer. As it turns out, the humorous timepiece required a skilled hand to use. Dangling from a string, it was difficult to read because of a tendency to move in the wind. Once researchers learned to wield it properly, they could read the hour. This included keeping the Sun on the left, moving the dial’s shadow to the correct month (represented by vertical lines), and counting horizontal stripes from the top to where the shadow starts. The quirky design is perhaps explained by Epicurean philosophy texts discovered at the Villa. Epicureans practiced humor, and the pig was one of their symbols. Only 25 such sundials exist, and the Herculaneum clock might be among the oldest.

1 The Secret To Chariot Racing

In the British Museum sits a 2,000-year-old toy chariot. Once the pride of a Roman boy, it was fished out of the Tiber Rivier in the 1890s. A recent reassessment provided much-needed information regarding the Roman version of Formula One. No racing chariots survive, but thankfully, the toy was a working model created by a craftsman with in-depth knowledge of the actual vehicles. Remarkably, it exposed the secret of how the charioteers prevented crashing during track turns. The bronze miniature’s right wheel showed signs of having an iron tire. This made sense. Races were run counterclockwise on oval tracks. During a high-speed left turn, the right wheel faced enormous structural pressures. Made from wood and rawhide strips, failure would have been common for the wheels without the reinforcing strip of iron. It’s not certain if adding the iron was mandatory or a choice. However, it would have increased chances of winning by 80 percent, purely because it made the chariot more hardy. The competitors with only two wooden wheels would have thinned at every turn. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages