10 Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is the process of drawing political boundaries to game the political system by giving one party a numerical advantage over the other. When one party controls the state legislature, they can redraw political boundaries in order to maximize the number of congressional districts that they can win. This creates severely skewed and unfair results, as they can be designed in such a way as to produce districts that consistently vote for a single party, as constituents for the other party are divided between districts. This can allow a party to win more electoral seats in spite of having a numerical disadvantage in the population. Watch this video on YouTube Gerrymandering is a uniquely American practice that can be traced back to a failed attempt to defeat James Madison. It became a common practice as territories became states in the late 19th century. The name itself comes from Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, who signed a redistricting plan to benefit his own party; the result on a map resembled a salamander. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 allowed for “affirmative gerrymandering” to create districts dominated by non-white constituents in order to redress historical discrimination. In 1993, the US Supreme Court found race-based gerrymandering unconstitutional but continued to allow for gerrymandering based on partisan politics. Some argue that the US is the only major democratic power that allows politicians to have an active role in creating voting districts, and it contributes to the divisive nature of American politics. But, as both major parties benefit from gerrymandering, the political will to reform the system doesn’t exist. Both Barack Obama and Tom DeLay have benefited from gerrymandering in their political careers. In spite of a lot of pressure to reform the system to ensure fairer and more competitive elections, as it stands, the problem is set to continue.

9 First-Past-The-Post Problems

The United Kingdom and other parliamentary systems rely on the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, in which the candidate with the most votes in each constituency is elected, and all other votes are discarded. It is easy to understand and count votes, and voters are able to clearly express who they want to vote for, so in a two-party system, FPTP usually produces a clear majority. Watch this video on YouTube It starts to fall down in a multi-party system, however, producing election results that do not accurately reflect the votes of the people. Officials can be elected with a relatively small percentage of the vote, it encourages tactical voting where people vote against who they dislike rather than who they like, many votes are meaningless, and small parties with votes spread widely across the country are penalized and unable to secure representation. One of the largest problems with the system is it allows for “landslide victories,” such as those enjoyed by Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, both of whom were able to form governments in spite of only receiving 30–40 percent of the popular vote. Without FPTP, many historical British governments would have needed to form coalitions with other parties rather than enjoying single-party domination in spite of only minority support. The 2015 election in the UK most clearly showed the severe limitations of the system, as the Conservatives won a clear majority in Parliament with only a third of the overall votes. Neither Labour nor the Conservatives won over 50 percent in any part of the country, yet it seemed like those were the only two parties who could possibly win. The system obscures divisions of political opinion within constituencies and exacerbates inter-region rivalry. A referendum to reform FPTP into a system called the Alternative Vote, in which voters rank their choices in order of preference, was rejected in 2011, but many in the country continue to be dissatisfied with FPTP.

8 Defective Democracies

Over the last 25 years, it has seemed like there has been a successful wave of democratization around the world, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet Union and more recently with the Arab Spring. However, this process may have been overstated. Since 2005, the number of defective or authoritarian democratic regimes has risen, particularly in South America and Eurasia. It has been said that of the 120 attempts of democratization which have occurred since 1960, 50 percent have been reversed. Liberal theorists have long thought that expanding middle classes helps to maintain social, economic, and political reform and rein in tendencies toward elected authoritarianism. However, in many countries, the middle class has shown itself more likely to support military coups against overzealous populist leaders. Many people in young democracies may feel nostalgic for their authoritarian past or believe that strong leadership is more important than political freedom. The usual reasons given for the failure of democracy are poor economic performance, reaction against economic reform, and the fact that presidential democracies are more vulnerable to authoritarian leaders than parliamentary democracies. According to Nathan Converse and Ethan Kapstein, this is backward. Many failed democracies have had good economic indicators, economic reform tends to reinforce democracy, and authoritarian prime ministers can be just as bad as authoritarian presidents. They instead claim that the greater reasons that democracies fail are economic inequality, unrestrained executive branches, and inefficient institution building. The latter is a particular problem in ethnically divided nations, as “us vs. them” politics trumps participatory inclusiveness. Further, democracy is likely to fail if the government cannot provide adequate levels of public goods like education and health care. The consequence of all this is that if developed countries want democracy to prosper in developing countries, they need to support the development of stable political parties, education, and health care provision and support the local private sector. The international community has too often supported an authoritarian leader who provides stability at the expense of local democracy.

7 Nonvoters

Voter turnout has apparently been in decline since the mid-1980s, which raises questions of whether a politically motivated minority can legitimately be said to represent the interests of the overall population. Declines in voter turnout have been seen across most of the democratic world, with the exception of Central and Eastern Europe, which are enjoying their honeymoon phase since the fall of the Eastern Bloc. Some see it as a moral failing and a case of apathy, while others see as an act of disengagement from a political system where you are more likely to die in a car accident than cast a crucial vote for any political issue. Some have blamed an increasingly paranoid and parochial style of politics, more interested in demonizing the opposition than debating the issues. Late political scientist Murray Edelman gave a justification: “Indifference, which academic political science notices but treats as an obstacle to enlightenment or democracy, is, from another perspective, a refuge against the kind of engagement that would, if it could, keep everyone’s energies taken up with activism: election campaigns, lobbying, repressing some and liberating others, wars, and all other political activities that displace living, loving, and creative work.” According to Pew Research polls, most nonvoters in the 2014 election were younger (70 percent under the age of 50), more racially and ethnically diverse, and less affluent and educated with weak partisan ties. Similar results were recorded in 2010 and 2012. On the other hand, there were only modest differences between voters and nonvoters over the issues and opinions of the major parties. Some fear that ever-shrinking numbers of voters could represent a threat to democracy, as it undermines the legitimacy of the entire system while bolstering the power of the system that they complain about. Others argue that active political participation is more useful to a healthy democracy than merely dropping a slip into a ballot box once every few years.

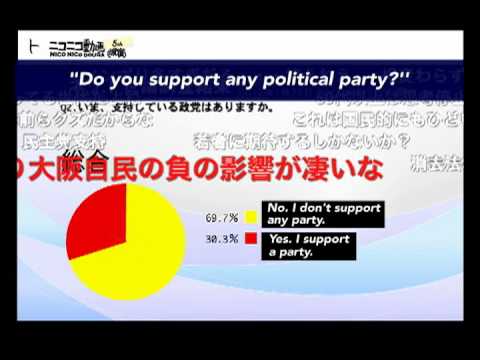

6 Japan’s Slightly Sham Democracy

Since 1955, Japan was ruled by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), a conservative party with center-right values. Some describe the Japanese democratic system as a “1.5 party” system designed to promote stability and long-term leadership rather than competition and plurality. In 1998, the Democratic Party of Japan was formed to push for Japan to become a truly two-party system, a task which they were believed to have succeeded at in 2009. But instability within the power and an inability to rein in the established bureaucracy stymied attempts at reform, and power shifted back to the LDP. Japanese democracy has long been a bit of a sham, but as long as things haven’t gone terribly wrong, most people have been content to let it be. As the society is economically strong and socially cohesive, the average person does not look to the government to do much and has very low expectations. When Shinzo Abe was reelected in 2014, it was in an election where only 52.66 percent of the population voted. In an Asahi Shimbun poll taken directly after the election, only 11 percent expressed satisfaction with Abe’s government. The problem was that 73 percent felt that the opposition parties offered them nothing to vote for. The problems may get worse if the political elites get their way. In 2012, the Liberal Democratic Party proposed revisions to the 1955 constitution, which makes sense considering that it was imposed by the US military. But many of their proposals seemed to go against the very spirit of modern democracy—rejection of the universality of human rights, “public order” elevated over individual rights, the elimination of free speech if it “damages the public order or public interest,” a shift in emphasis from individuals rights to citizen duties, hindering the freedom of the press, and giving greater power to the prime minister to amend and suspend the constitution.

5 The Chinese Challenge

The economic and political rise of Chinese power under the stewardship of the Chinese Communist Party represents a direct challenge to the existing pro-democratic world order by providing the example of a non-democratic country succeeding on the world stage. While the modern Chinese are not promoting a cohesive anti-democratic ideology like communism or fascism, they undermine the narrative of the inevitable onward march of liberal democracy. In a Journal of Democracy article, Andrew Nathan identifies six negative effects that China has on the global democratization project. China’s success encourages other authoritarian and illiberal regimes to believe that they can achieve modernization without democratization. They also spread authoritarian values as a side effect of their propaganda efforts to look good on the world stage. China spreads technologies and techniques of oppression to its authoritarian partners and seeks to undermine democracy in areas where it exerts influence, such as Macau, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Its support for authoritarian allies also extends to economic, military, and diplomatic support. Finally, China is using its clout to make international institutions like the United Nations more value-neutral in regards to regime types instead of being organs to further the spread of democracy. Many assume that China will become democratic as it becomes richer, given the many historical precedents. However, this is not assured. Unlike the Soviet Union, China has a smooth system of political transition which promotes stability and has been experiencing solid economic growth. The Chinese system features a political elite based on meritocracy, with internal but not external competition, and an informal relationship with the population. Their model may not be sustainable in the long run. But the danger for the time being is that it looks like it’s working. Economic and political problems in liberal democracies run the risk of standing in sharp contrast with a (seemingly) stable and successful anti-democratic regime in China, encouraging the stability of authoritarian regimes and the rise of illiberal politics in developed countries.

4 Europe’s Democracy Deficits

Euro-skeptics in the United Kingdom are quick to criticize a so-called “democracy deficit” in the European Union. The idea is that Brussels wants to push “federalism,” so member states lose the ability to make decisions for themselves, and power is held by an elite of continental technocrats. Some argue that this is a definitional problem, while in the UK, federalism suggests a European super-state. It was defined by Swiss political scientist Andreas Gross as “a process of balancing power in a differentiated political order which enables unity while guaranteeing diversity.” The debate between nationalists and federalists is very real, even if they may be talking past each other. The Greek crisis has illustrated the problems of combining a common currency market with nation-state autonomy on fiscal matters. In a truly federal Europe, there could be a common fiscal policy in place, and it would be easier for more economically developed regions help support less economically developed regions. There’s a reason that no one in the US is trying to kick out or extort money from economic underperformers like Mississippi, New Mexico, and Arkansas. According to US political scientist Dan Kelemen, there is a larger problem looming—the hollowing out of democracy within individual member states and the inability of the EU to do much about it. The most glaring recent example is in Hungary, where the government of Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party has been dismantling political checks and balances such as the independence of the judiciary, taking over the media, and allowing business to be taken over by Fidesz-friendly oligarchs. This is essentially a Putin-style, one-party state emerging in the middle of the European Union. The fundamental values of the European Union were set down in the Lisbon Treaty—respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, and the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of minorities. But the European Union was originally mainly concerned with business and building a common market, and there is little in the European political and legal system to deal with emerging illiberal rogue states. Article 7 does allow for a member state to be stripped of its voting rights if it violates Europe’s fundamental values. However, this can only be used if agreed upon by the European Commission, the European Parliament, and all member states. It is considered a nuclear option, as it is feared that it could destabilize the Union, and many member states fear that it could be used against them in the future.

3 The US Two-Party System

The United States considers itself to be the greatest democracy in the world, but some in multi-party democratic states scoff at the fact that US democracy is effectively limited to two choices. There were actually 52 alternative political parties running in the 2014 US elections, from more well-known examples like the Libertarian, Green, Constitution, and Reform Parties to more off-the-wall examples such as the Blue Enigma, Marijuana, NSA Did 911, and Sapient Parties. In spite of this range of options, it is only ever the Democrats or the Republicans that win elections. Americans have not had a third-party candidate win an election since Abraham Lincoln defeated the candidates for the Democrats and Whigs in 1860. Historically, third parties have largely served an upset role, drawing votes away from one candidate and allowing the other to win. The largest obstacle facing third parties is the single member district plurality (SMDP) system, a winner-takes-all system in which the person with the most votes in an electorate wins the seat. This practice extends to the presidential race as well, with each state awarding all its electoral votes to the candidate who achieves a plurality in the state (except Maine and Nebraska). In such a situation, even if a third party statistically has support in the low double-digits percentage across the country, they are not going to win representation anywhere. It’s better to simply join with one of the two main parties or withdraw. The system encourages the formation of broad-based parties able to win in the SMDP Electoral College. There are psychological barriers to voting for a third party, as most voters assume it’s a wasted vote, and indeed, third parties tend to be organized around a single individual and issue and are unlikely to gain widespread support from the electorate. There are also economic barriers, as campaign finance rules mean that third parties cannot get government funding unless they have won a certain percentage in an earlier election. Significant paperwork is required to register a third-party presidential candidate, and the media pays little attention to third-party candidates except as novelties. The result is that the self-proclaimed greatest democracy in the world still boils down to a choice between A and B.

2 India’s Corrupt Elections

India is considered the largest democracy in the world, but some in the country believe that it is not an entirely functional one. The country is still plagued by immense poverty, high rates of illiteracy, social and economic inequality, and an entrenched culture of political corruption. While more than four dozen political parties exist in India, only three are not under the complete control of a political family dynasty or a charismatic leader. Other than parties with extreme ideologies, most mainstream parties resemble each other in their behavior and policy platforms. According to M.R. Narayan Swamy, executive editor of the Indo-Asian News Service, “Ideology has been pushed to the periphery; personal ambition is the sole motivating factor for most party workers in most parties.” Corruption remains a major problem for all parties. In 2014, election officials seized 22.5 million liters (5.9 million gal) of illegal alcohol, $52 million in cash, and even 181,000 kilograms (400,000 lb) of marijuana and heroin, which were being used by political candidates to entice votes. At party rallies and meetings, party workers give gifts to prospective voters—laptops, booze, and cash. Things were so bad that the Election Commission was forced to set up 11,123 “Flying Squads” of police and magistrates to tail election candidates armed with video cameras to make sure they didn’t engage in any illegal campaigning. Still, the overall situation has improved since periods in the past, where political parties would hire thugs to take over polling stations. Now, they just pay TV stations and newspapers to give them only positive coverage. Dr. Michael Kugelman, Senior Program Associate for South and Southeast Asia AT Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, believes that India is indeed a working democracy, and corruption is a feature found in every democratic country. However, “India’s scandals seem to be so much bigger—involving more money and abuses of power—than seems the norm. Such corruption helps explain why politicians are so unpopular in India, and in the long term—if not addressed—this systemic corruption could imperil the social contract between people and state that is meant to embody democracy.”

1 Elite Theory

Theorists like Gaetano Mosca, Vilfredo Pareto, and Robert Michels purported the idea that aspiring to egalitarianism and democracy are essentially futile efforts. Mosca believed that a political elite making up a tiny minority would always be able to outmaneuver the mass of the population and seize control of power. Pareto argued that, while in a perfect world, the elites would be made up of the most deserving, in reality, the existing elites use force, persuasion, and inherited wealth to maintain their position. Michels argued that large organizations need leaders and experts to succeed efficiently, but power concentrates in their hands as they gain control of funds, information, power over promotions, and other aspects of organizational control. This mode of thought suggests that elite rule is perpetuated by a separate elite culture able to exert power over the disorganized masses. Power-elite theorist C. Wright Mills claimed that the governing elite of the United States was essentially composed of three groups—the highest political leaders like the president and his cabinet members and advisers, the major corporate owners and directors, and high-ranking military officers. The elite is not a closed group, nor does it have to rely on oppression or deception in order to maintain a grip on power. Instead, the elites rely on a similar overall worldview and ability to coordinate on basic issues. Members of the US elite believe in the free enterprise system based on profits and private property, unequal and concentrated wealth distribution, and the sanctity of the economic realm. The primary business of government is creating a favorable business climate, with social and environmental concerns as afterthoughts. Though they may squabble over details, members of the elite maintain this basic overall worldview based on their common culture: They attend the same universities, join the same clubs, and participate in the same social activities. This elite controls the basic choices and sets the political agenda. Professional politicians occupy a middle layer of power—colorful and bombastic but essentially squabbling over trifles and serving as a distraction. Below them is the public at large, who are either obsessed with the political circus and spend most of their time cheering on their chosen team or booing the opposition or who have largely lost interest in political participation. The direction of fundamental policy choices is out of the control of the people at large. Pluralist theorists argue that elite theory fails to take into account the rise of popular social movements and their effect on the political system, which has historically forced economic and social change in spite of the interests of the elite. Some say that a distorted view of elite theory has led to an unhealthy rise of conspiratorial thinking, where people blame world events on a shadowy international cabal of puppet masters like the Bilderberg Group. Vote for David Tormsen and win a free laptop. Email him at [email protected].