World War II was one of the most death-filled chapters of our history, with at least 60 million people dying as a result. Some of those people left behind final written words. For some, this was an accident and their last words were just another letter for them. Still others were staring death in the face and knew there were things that they couldn’t leave unsaid. The letters below offer glimpses into the writers’ minds, their characters, and their priorities during the most difficult period in human history and their own lives.

10 Thoughts Before A Kamikaze Attack

On May 11, 1945, Ryoji Uehara, 22, was killed in action as a member of the Army Special Attack Unit (commonly known as kamikaze pilots) during the Battle of Okinawa, the bloodiest battle of the Pacific theater. The night before his suicide mission, he wrote a letter containing his thoughts about the war and his role in it. He begins the letter by acknowledging, “I am keenly aware of the tremendous personal honor involved in my having been chosen to be a member of the Army Special Attack Corps, which is considered to be the most elite attack force in the service of our glorious fatherland.” But Uehara was more than a willing soldier. He was not blind to what led his country to the situation it was in. Though he was still willing to fulfill his mission, his thoughts lingered on an ideology that was contrary to his country’s at the time. He wrote: It is equally inevitable that an authoritarian and totalitarian nation, however much it may flourish temporarily, will eventually be defeated. In the present war, we can see how this latter truth is borne out in the Axis Powers themselves. What more needs to be said about Fascist Italy? Nazi Germany, too, has already been defeated, and we see that all the authoritarian nations are now falling down one by one, exactly like buildings with faulty foundations. All these developments only serve to reveal all over again the universality of the truth that history has so often proven in the past: Men’s great love of liberty will live on into the future and into eternity itself. On the kamikaze pilot’s role, he said: In a real sense, it is certainly true that a pilot in our special aerial attack force is, as a friend of mine has said, nothing more than a piece of the machine. He is nothing more than that part of the machine which holds the plane’s controls—endowed with no personal qualities, no emotions, certainly with no rationality—simply just an iron filament tucked inside a magnet, itself designed to be sucked into an enemy aircraft carrier. The whole business would, within any context of rational behavior, appear to be unthinkable and would seem to have no appeal whatsoever except to someone with a suicidal disposition. I suppose this entire range of phenomena is best seen as something peculiar to Japan, a nation of spirituality. So then we who are nothing more than pieces of machinery may have no right to say anything, but we only wish, ask, and hope for one thing: that all the Japanese people might combine to make our beloved country the greatest nation possible. Uehara ended his letter, “I have said everything I wanted to say in the way I wanted to say it. Please accept my apologies for any breach of etiquette. Well, then.”

9 Toshihiro Oura’s Last Diary Entries

During World War II, Probational Officer Toshihiro Oura was stationed on the southwest tip of New Georgia. In June 1943, US forces began a campaign to capture the island. A major goal was to seize the airfield at Toshihiro Oura’s position. Oura maintained a diary throughout that time. Although his ultimate fate remains a mystery, it’s unlikely that he survived. His last entries tell the tale of a man defeated but determined to keep some measure of hope. In his second-to-last entry on July 22, he wrote in part: Just think: I haven’t washed my body or my face nor have I brushed my teeth for a month already. One of my upper front teeth has been broken off. My body smells like that of a wild dog. Only by staying in the dugout can I say that I’m still alive. The drum in front of the dugout is full of holes. A piece of shrapnel hit my back, and I thought I was finished. Mysteriously, there were no deaths. We had to do away with a standing guard. We’re just leaving everything open to the enemy. Oh, friendly forces! Please come to our aid! Show them the might of the Japanese army. His last entry on July 23 revealed his bitterness over the war’s outcome and his thoughts on his own death: Battle Situation: Nothing aside from annihilation. No cooperation from the navy. If I were to compare the complete cooperation of the enemy, it would be like the war of a child with an adult. Our mountain artillery positions were knocked to pieces by enemy tanks. We are encircled, so they say, and about to be overrun. Consequently, all we can do is to guard our present positions. What in the world could our forces at Rabaul or the staff of Imperial headquarters be doing? Where have our air forces and battleships gone? Are we to lose? Why don’t they start operations? We are positively fighting to win, but we have no weapons. We stand with rifles and bayonets to meet the enemy’s aircraft, battleships, and medium artillery. To be told we must win is absolutely beyond reason. If we, as well as the enemy, were to fight to the end with all available weapons, then I would be willing to give up, whether we win, lose, be injured, or be killed. But in a war like this, where we are like a baby’s neck in the hands of an adult, even if I die, it will be a hateful death. How regretful! My most regretful thought is my grudge toward the forces in the rear and my increasing hatred toward the Operational Staff. In the rear, they think that it is all for the benefit of our country. In short, as present conditions are, it is a defeat. However, a Japanese officer will always believe, until the very last, that there will be movements of our air and naval forces. He ends his last entry with the unceremonious words, “There are signs that I am contracting malaria again.” Few Japanese soldiers escaped or were taken prisoner, so it is unlikely that Oura survived the battle. Four days after his last entry, the remaining Japanese forces withdrew from the area. On August 5, the airfield was captured by US forces.

8 Private Harry Schiraldi’s Last Words Home

Harry Schiraldi served as a medic in the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division during the Normandy landings. He sent this letter to his mother before the battle, detailing some of his everyday activities and reassuring his mother that he didn’t neglect his faith or his love for her: Dear Ma, Just a few lines tonight to let you know that I’m fine and hope everybody at home is in the best of health. I just finished playing baseball and took a nice shower and now I feel very nice. Hope everything is going alright at home, and don’t forget, if you ever need money, you could cash my war bonds anything [sic] you want to. This afternoon, I went to church and I received Holy Communion again today. Getting holy, ain’t I? Well, Ma, that’s all I got to say tonight, so I’ll close with my love to all and hope to hear from you very soon. Take care of yourself. One of your loving sons, Harry Schiraldi was killed by enemy gunfire the morning of the Normandy landings. He is buried now in the Calvary Cemetery in New York.

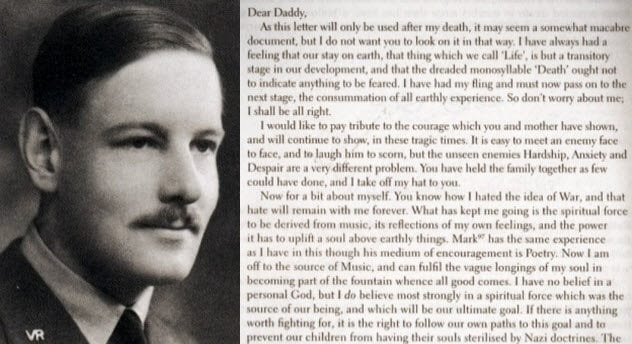

7 Michael Andrew Scott’s Letter To His Father

Michael Andrew Scott was one of eight children. When the war began, he was employed as a teacher. But he enlisted and eventually served with the Bomber Command’s 110 squadron. Scott kept a diary where he discussed the futility of the war, his sense of duty, and his love of music. He also wrote a letter to his father for delivery in the event of his death. Dear Daddy, As this letter will only be used after my death, it may seem a somewhat macabre document, but I do not want you to look on it in that way. I have always had a feeling that our stay on Earth, that thing which we call “Life,” is but a transitory stage in our development and that the dreaded monosyllable “Death” ought not to indicate anything to be feared. I have had my fling and must now pass on to the next stage, the consummation of all earthly experience. So don’t worry about me; I shall be all right. I would like to pay tribute to the courage which you and mother have shown, and will continue to show, in these tragic times. It is easy to meet an enemy face to face and to laugh him to scorn, but the unseen enemies Hardship, Anxiety, and Despair are a very different problem. You have held the family together as few could have done, and I take off my hat to you. He ended with, “All I can do now is to voice my faith that this war will end in victory and that you will have many years before you in which to resume normal civil life. Good luck to you! Mick.” Scott was killed over the English Channel while flying formation with a fighter escort. His last diary entry was on May 18, 1940. His diary was returned to his family, and the final entry in his diary was added by Flora, his sister. It read: “Missing. Believed Killed. No further news of Mick was ever heard.”

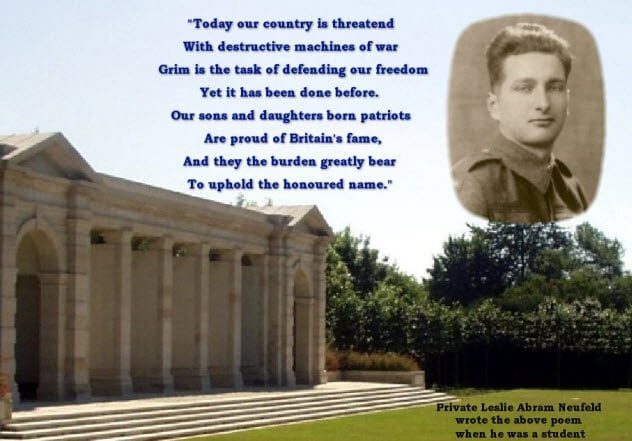

6 Canadian Paratrooper’s Letter Before D-Day

Private Leslie Abram Neufeld was a 21-year-old who had grown up with his eight siblings on a farm in Saskatchewan. He and two of his brothers enlisted in 1942. Leslie served in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corp with his brother Leonard. When the army asked for volunteers to join the 1st Parachute Battalion, Leslie volunteered willingly and entered into an intense training regimen. He and his battalion were scheduled to drop during Operation Overlord, known more commonly as D-Day. During the anxious wait before the attack, he wrote his family goodbye, just in case. Dear parents, brothers, and sisters, My time for writing is very limited. However, I must write a few words just to let you know how things are going. First of all, thanks a million for the cigs and parcels and letters. Received your letter, Dad, just a day ago. By mistake, I received Len’s cigs, too. Sorry, Mum, that I don’t have time to answer all your questions now. Dad, the time has come for that long-awaited day, the invasion of France. Yes, I am in it. I’ll be in the first 100 Canadians to land by parachute. We know our job well. We have been trained for all conditions and circumstances. We have a fair chance. I am not certain, but I expect Len will be coming in a few days later. To go in as a paratrooper was entirely my choice. I am in no way connected to any medical work. This job is dangerous, very dangerous. If anything should happen to me, do not feel sad or burdened by it, but take the attitude of “He served his country to his utmost.” With that spirit, I am going into battle. And let it be known that the Town of Nipawin did its share to win the war. I have full expectations of returning, and with God’s strength and guidance, I’m sure He will see me thro’ all peril. My trust is in God. Your loving son, Leslie Leslie’s company parachuted into Varaville. Their goal was to destroy a bridge over the River Dives and prevent German troops from crossing the river from the east. He and a Corporal Oikle arrived at Chateau Varaville and fired on the enemy. Their attack fell short, and the Germans retaliated with a high-explosive shrapnel shell. Leslie was killed instantly and buried beneath debris. His letter was delivered after his family was notified of his death. His brother Edward said it was “the only time I ever saw my father cry.”

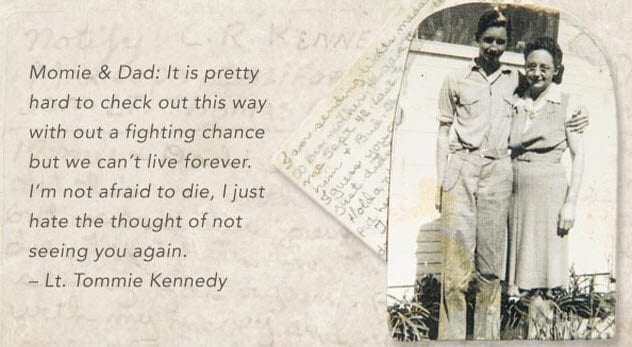

5 POW’s Letter

During the war, Lieutenant Tommie Kennedy, 21, was captured by the Japanese. He spent nearly three years as a prisoner of war and was fatally malnourished. His only means to write a letter home was to scribble the words on the back of two family photos he had managed to keep. Momie & Dad: It is pretty hard to check out this way without a fighting chance, but we can’t live forever. I’m not afraid to die, I just hate the thought of not seeing you again. Buy Turkey Ranch with my money, and just think of me often while you’re there. Make liberal donations to both sisters. See that Gary has a new car his first year in high school. I am sending Walt’s medals to his mother. He gave them to me Sept. ’42 last time I saw him & Bud. They went to Japan. I guess you can tell Patty that fate just didn’t want us to be together. Hold a nice service for me in Bksfield & put headstone in new cemetery. Take care of my nieces & nephews. Don’t let them ever want anything as I want even warmth or water now. Loving & waiting for you in the world beyond. Your son, Lt. Tommie Kennedy His letter survived him and was passed from one POW to another until it was able to be mailed. His parents received his goodbye some four years after he had originally been deployed to the Pacific.

4 An Unknown Holocaust Victim’s Letters

These letters were found in the city of Tarnopol, which was home to 18,000 Jews before the war. Only 150 survived. Who this woman was or how she eventually met her end is unknown. All that remains are these two letters. Tarnopol 7 April 1943. Before I leave this world, I want to leave behind a few lines to you, my loved ones. When this letter reaches you one day, I myself will no longer be there nor will any of us. Our end is drawing near. One feels it, one knows it. Just like the innocent, defenseless Jews already executed, we are all condemned to death. In the very near future, it will be our turn, as the small remainder left over from the mass murders. There is no way for us to escape this horrible, ghastly death. At the very beginning (in June 1941), some 5,000 men were killed, among them my husband. After six weeks, following a five-day search between the corpses, I found his body. Since that day, life has ceased for me. Not even in my girlish dreams could I once have wished for a better and more faithful companion. I was only granted two years and two months of happiness. And now? Tired from so much searching among the bodies, one was “glad” to have found his as well; are there words in which to express these torments? Tarnopol 26 April 1943. I am still alive, and I want to describe to you what happened from the 7th to this day. Now then, it is told that everyone’s turn comes up next. Galicia should be totally rid of Jews. After all, the ghetto is to be liquidated by the 1st of May. During the last days, thousands have been shot. Meeting point was in our camp. Here the human victims are selected. In Petrikow, it looks like this: Before the grave, one is stripped naked, then forced to kneel down and wait for the shot. The victims stand in line and await their turn. Moreover, they have to sort the first, the executed, in their graves so that the space is used well and order prevails. The entire procedure does not take long. In half an hour, the clothes of the executed return to the camp. After the actions, the Jewish council received a bill for 30,000 zloty to pay for used bullets. Why can we not cry, why can we not defend ourselves? How can one see so much innocent blood flow and say nothing, do nothing, and await the same death oneself? We are compelled to go under so miserably, so pitilessly. Do you think we want to end this way, die this way? No! No! Despite all these experiences. The urge for self-preservation has now often become greater, the will to live stronger, the closer death is. It is beyond comprehension.

3 Letter From Jehovah’s Witness Before The Guillotine

Gerhard Steinacher became one of Jehovah’s Witnesses when he was only 17. He was arrested on September 15, 1939, for his conscientious objection to military service and for his refusal to swear an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler. Steinacher was imprisoned in Vienna for six weeks. Then he was transferred to Berlin, charged with subverting the war effort, and sentenced to death by the Reich Military Court. Hours before his execution, Steinacher was allowed to write a letter to his family, though three lines were censored by his Nazi captors. Dear Mother and Father, Well, there is no point in saying much. I was informed two hours ago, at 7:00 PM, that I’m to be executed tomorrow at 5:50 AM. The moment has arrived, Lord give me strength, yes, the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak. I am sitting here in a cell, it’s about 1:00 AM, two other men are in here with me, time is rushing by, I am writing this letter in stages as things come to mind. It’s cold outside, snowing again. May the Lord give you strength. I want to work, and I’ve promised both orally and in writing that I will work ambitiously and be completely content. However, I just can’t shoot and everything revolves around this one point. Now, let the Lord’s will take place; what is to happen cannot be stopped. Be strong, do not let this weaken you, but let it bring you closer together, do not give up. I am still a child, and I can only stand if the Lord grants me the strength, and I ask him to. I received your last letter marked March 25. The 25th, the last greetings from you. Now it’s around 3:30 AM. I never thought this would all happen so fast. [Three lines were censored here by the Nazis.] . . . surprise and so you never know what will happen from one minute to the next. You will get my belongings. Pens, papers and letters, money and clothing, key, and some other things. Please give my warmest greetings to my grandparents, Resi, Uncle, Aunt, Grandma and Grandpa, Mr. and Mrs. Hock. To all my workmates, everyone who knows me and all my relatives. Father, be strong, do not give up, do not fall apart, but be strong in your faith as in everything else. And you, Mother, be strong and firm and support one another. Beg the Lord that He protects you, gives you power and hope and directs everything so that you stay on the right path and that nothing happens to you. I will also ask Him on your behalf. As the hour draws closer, I really realize how weak we are. Up to this point, I have always had the chance to change my mind. I want to work, but I just can’t shoot. So now I will finish. I greet and kiss you, dear Father and Mother, I will always be your Gerhard, 100,000 times over, who longed to be with you. Until we see each other again in the Kingdom, where all four of us will be together again. Be of good cheer. A million kisses. Gerhard was beheaded on March 30, 1940, for his refusal to kill another human being. He was only 19 years old.

2 Another Witness Refuses To Kill

Wolfgang Kusserow and his entire family were under close watch from the Nazi secret police because of their religious activities. As one of Jehovah’s Witnesses, he believed that God—and not Hitler—was deserving of his loyalty. Even after his father and mother were arrested for this, Kusserow continued to hold illegal Bible study meetings in his home. Like Gerhard Steinacher, Kusserow refused to join the German military effort and was arrested in December 1941. He, too, was tried and sentenced to death. Kusserow wrote to his family on the night before his execution was carried out. My dear parents and my dear brothers and sisters! One more time, I am given the opportunity to write you. Well, now I, your third son and brother, shall leave you tomorrow early in the morning. Be not sad, the time will come when we shall all be together again. Those who will sow with tears will reap with joy. “Those sowing seed with tears will reap even with a joyful cry.” How great the joy will be when we see all of us again, although it is not easy now to overcome all this, but through belief and hope in the King and His Kingdom, we conquer the worst. “For I am convinced that neither death nor life nor angels nor governments nor things now here nor things to come nor powers nor height nor depth nor any other creation will be able to separate us from God’s love that is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38–39). So we confidently look forward to the future. After addressing each member of his family individually, Kusserow ends his letter, “A last greeting from this old world in the hope of seeing you again soon in a new world. Your son and brother, Wolfgang.” Wolfgang was killed on March 28, 1942. He was 20 years old. All told, about 10,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses were sentenced throughout the Nazi period for refusing to give the Nazi salute, join political party organizations, enroll their children in Hitler’s Youth, participate in so-called elections, or decorate their homes with Nazi flags. As many as 3,300 were sent to concentration camps. Of those, 1,400 died and 250 others were executed.

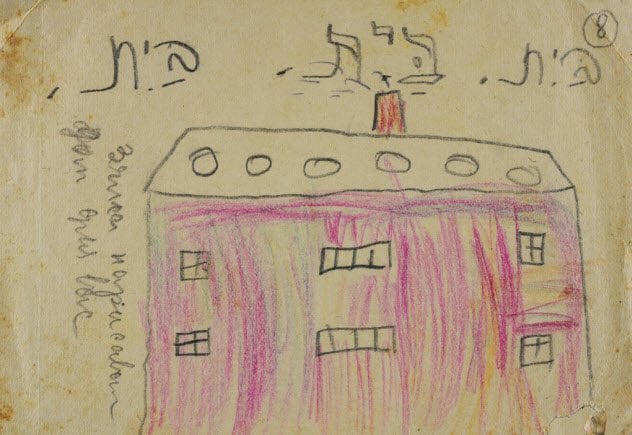

1 A Nine-Year-Old’s Thank You

Zalman Levinson was a nine-year-old boy who lived with his mother, Frieda, and his father, Zelik, in Riga, Latvia. They stayed in regular communication with Frieda’s sister, Agnes, in Israel, who would send gifts to Zalman. Frieda sent Agnes a postcard from Riga in April 1941. After that, the letters suddenly stopped. We know now that the family’s names were included on a list of inmates at the Riga ghetto, where about 30,000 Jews were held captive. In late 1941, Germans declared that they would be moving the ghetto’s inhabitants and settling them “further east.” Between November 30 and December 9, at least 26,000 of these Jews were killed southeast of Riga along the Riga-Dvinsk railway. It is likely that this is where the Levinsons, including Zalman, were killed. The last letter that Frieda received from her nephew was a colorful drawing of his house and a brief letter he had written himself. The letter to his aunt was signed with his name and a brief, “Thank you for the present.”