See Also: Top 10 Bizarre Aspects of Catholicism

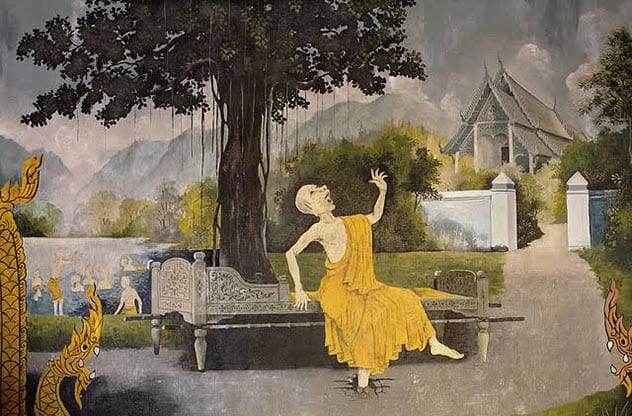

10Devadatta’s Schism

The shortest lasting schism on this list, as most of them exist in some way up to the present day, Devadatta’s schism was an event which occurred in the early days of Buddhism. A cousin of the Buddha, he sought to impose stricter laws on his fellow monks, insisting they be increasingly ascetic in their lifestyle. (One of the harshest measures was that he believed they should not live in buildings, instead dwelling in the forest for all their lives.) He then sought to take over the leadership role, but the Buddha rebuffed his advances, even going so far as issue a formal act of proclamation against Devadatta, who grew increasingly angry at the Buddha. His wrath manifested itself in the form of three separate assassination attempts: (1) hired assassins who, instead of killing the Buddha, were converted, (2) attempting to roll a boulder off the side of a mountain, and (3) letting an elephant loose while the Buddha was collecting alms. All were unsuccessful. Though he initially managed to convince 500 Buddhists to join him, Devadatta and his schism eventually faded into obscurity. (There were stories of some adherents as late as the 7th century.) Some Buddhist legends have him spending eons in Naraka, a sort of Buddhist hell.[1]

9The Radical Reformation (Anabaptism)

A split from Protestantism, though some debate that point, Anabaptism was formed in the early 1600s, along with a handful of other new sects. Their major concern, and biggest split with “traditional” Christianity, was that they believed in adult baptism, a belief that baptism was only valid if the person understood what they were doing and in what they believed. They were also rabid pacifists and refused to swear oaths, acts which greatly increased their persecution. The most widely known story involving Anabaptists is the Münster Rebellion. Radicalized Anabaptists, led by a triumvirate of Bernhard Rothmann, Jan Matthys and Jan van Leiden, sought to create a communal paradise in the German city of Münster. Eventually, the situation deteriorated into a siege, with Matthys dying in a vain attempt to become a second Gideon. Van Leiden then became leader and polygamy soon followed. Eventually, the besiegers took the city, executing a number of prominent Anabaptists. The iron baskets in which their bodies were displayed still hang from the steeple of St. Lambert’s Church, with the corpses themselves removed about fifty years later.[2]

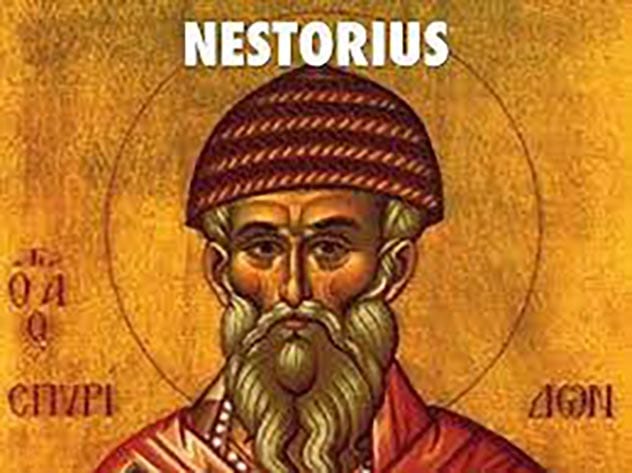

8 The Nestorian Schism

Nestorius was the Patriarch of Constantinople, widely seen as the spiritual leader of Eastern Orthodoxy, in the 5th century and the controversy in which he soon found himself embroiled centered around that Jesus Christ was not both fully divine and fully human; rather, he was two separate people in the same body, one fully divine and one fully human. He quickly found a formidable enemy in Cyril, the Patriarch of Alexandria. He also wanted to change the Virgin Mary’s long-used title from Theotokos (“Bringer forth of God”) to Christotokos (“Bringer forth of Christ”). He was eventually condemned during the Council of Ephesus in 431 and subsequently exiled by Emperor Theodosius II. (His condemnation was later upheld at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.) Perhaps the most interesting note of Nestorianism is that a number of Mongol leaders were adherents of the religion, none more so prominent than the great Mongol queen Sorqoqtani.[3]

7 The Khawarij Schism

The second real schism which Islam faced, the Khawarij formed a sect as a result of the outcome of the Battle of Siffin, the last fight in the First Fitna (Muslim civil war). When Ali ibn Abi Talib, the reigning Caliph and a cousin of the prophet Muhammad, was forced to resign, turning over the Caliphate to the rebellious Muawiyah I, the Khawarij proclaimed their anger, claiming the negotiations which were taking place were against God and they refused to recognize either claimant. In fact, their beliefs eventually led them to protest any governmental rule, citing Quran 6:57 and saying “No command but God’s”. This overriding belief, as well as internal strife, eventually led to the slow decline and eventual dissolution of their sect. However, before their sect was completely gone, they managed to assassinate Ali, by striking him with a poison-coated sword. (They also failed in an attempt on Muawiyah I’s life.)[4]

6 The Gnosticism Schism

Derived from the Greek word gn?sis, which means knowledge, Gnosticism is often seen as an offshoot of early Christianity, though there are some that believe it actually originated within Judaism. Either way, the overriding belief which united Gnostics was that the physical world was a trap, one which inhibited the accumulation of knowledge, which lay in the spiritual world. They also separated from Judaism and Christianity on the subject of creation; for Gnostics, there is an overriding all-powerful God and one of his emanations, a figure known as the demiurge, created the physical universe. Since God is completely spiritual, their prevailing goal in life is to get as close to the spiritual world as possible because humans are “sparks” of God, trapped in physical bodies. Gnosticism itself underwent a number of schisms and, while most of them disappeared into the fog of the past, some groups, especially Mandaeism, have survived to this day.[5]

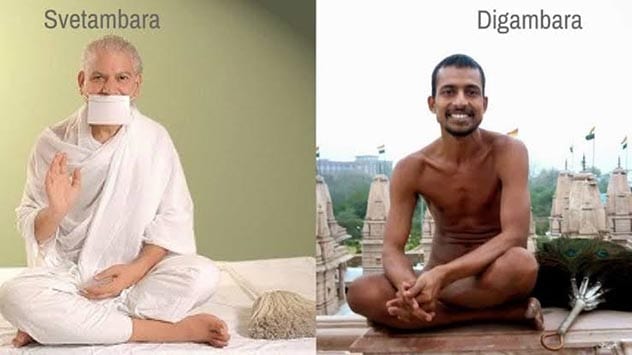

5 Digambara vs. Shvetambara

One of the oldest religions, with some scholars putting their origins in the 6th century B.C., Jainism is a peaceful, ascetic religion, one whose overriding motto is Parasparopagraho Jivanam, which loosely translates as “All life is bound together by mutual support”. Shortly after its establishment, Jainism split into two schools of thought, both of which remain the dominant beliefs within the religion. The first is Digambara, Sanskrit for “Sky-clad”, a sect in which the ascetic life is taken to such an extreme that the male adherents don’t even wear clothes. (The female adherents wear unstitched saris.) What else separates them from their fellow Jains is the beliefs that perfect saints need no food, that their last savior/spiritual leader Mahavira never married, and that women can’t reach moksha (“spiritual release”) without first becoming a man. Their counterparts are the Shvetambara, Sanskrit for “White-robed”, a sect in which the believers wear simple white clothing, as they don’t believe ascetics have to remain nude. Other than the above differences, the two sects share the same doctrine, more or less.[6]

4The Protestant Reformation

Most famously expressed, and started, by Martin Luther publishing his “Ninety-Five Theses” in 1517, the Protestant Reformation sought to purify the Catholic Church of ills which its adherents felt were leading true Christians astray. Chief among them was the practice of indulgences, wherein sinners could have their time in Purgatory lessened through the performance of good works or, to Protestant’s horror, paying the Church. None of this was novel, however, as reformers had attempted numerous times in the past to convince the Church to give up the practice of indulgences. What set Luther apart was the printing press and he put it to incredible use, reaching many more people than any of his predecessors. (His translation of the Bible from Latin to German was also of immense help.) Initially hoping to stay within Catholicism, he was excommunicated in 1521. When all was said and done, Protestantism became the third largest denomination in Christianity, just behind Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[7]

3The Arianism Schism

Arius was a Christian theologian in Alexandria during the 3rd and 4th century A.D.; his place in history is a result of his religious disputes with Athanasius, another Christian theologian in Alexandria. The main tenet of Arianism was that Jesus Christ was created by God, which meant he wasn’t a part of the Trinity. Though he never gave a specific date for Christ’s creation, Arius nevertheless held that God was alone at some point, whereupon he created his son. Athanasius, along with a few other critics, maintained this turned Christianity into a polytheistic religion and completely destroyed the Christian idea of salvation. For decades, Arianism was a popular alternative to “mainstream” Christianity and the debate was eventually settled at the First Council of Nicea in 325, where the sect’s teachings were officially deemed to be false. However, subsequent Roman emperors were more open to Arianism and it began to flourish again. By the end of the 5th century, Arianism had faded to near-extinction, with only a few adherents, especially the Germanic tribes.[8]

2 Sunni-Shia Split

Shortly after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632, a problem arose in the recently formed religion of Islam: who would be his successor as spiritual leader? This ended up being the problem which split the Muslim world in twain. Adherents of the Sunni sect felt the Muslim community was right in electing Muhammad’s father-in-law Abu Bakr to become the first caliph, whereas the Shia felt Muhammad had actually intended for his son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib to take on the role. In the end, the Sunnis seemingly won out, as they represent as much as 90% of the total worldwide Muslim population. Interestingly enough, this Ali is the same as the one mentioned in the Khawarij Schism above. (Yes, he was both Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law.) Even though he was elected to be the fourth caliph, that wasn’t enough to bring the two sects together and they’ve drifted apart ever since. (Ali’s son, Hussein, was later massacred by the new Sunni caliph, whom he refused to recognize.)[9]

1 The Great Schism

Otherwise known as the East-West Schism, the Great Schism was one of the most momentous occasions in Christianity’s history and what resulted was the creation of Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. In 1054, the differences between the western and eastern churches had reached a boiling point; eastern leaders were upset at the west’s strict doctrine of clerical celibacy and the western leaders were upset at the east’s desire to use leavened bread in the Eucharist (Holy Communion) and their rejection of Christ as a source of the Holy Spirit. Finally, there was the practical issue of whether or not the pope had authority over the patriarchs, or vice versa. This culminated in the dual excommunications of Pope Leo IX and Michael Cerularius, the Patriarch of Constantinople. (Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras eventually revoked those decrees in 1965.) Though reconciliation seemed possible at the time, with a number of different attempts made in the following centuries, eventually the two Churches grew into distinct entities.[10]