While green is its most common hue, jade can be any color. In 1863, scientists discovered that jade refers to two silicate metamorphic stones: nephrite, ideal for sculpting, and jadeite, which can be stronger than steel. The Maya and the Chinese prized jade over any other material—even gold.

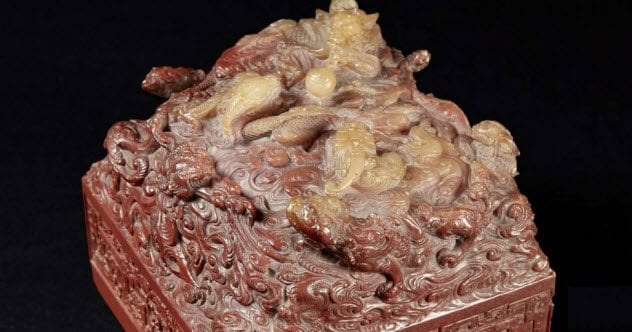

10 Record-Breaking Red Jade Imperial Seal

In December 2016, an 18th-century Chinese imperial seal sold at auction for 21 million euros. Dated from the Qianlong period between 1736 and 1795, this symbol of imperial authority is carved from red and beige nephrite. After a bidding war, an unnamed Chinese collector snatched it up. The seal sold for 20 times its estimated value, shattering the previous record of 12.4 million euros paid for a jade stamp in 2011. The seal once belonged to Emperor Qianlong. Pieces from the period are considered a high point of Chinese art. The jade, described as “almost blood red,” is extremely rare. Nine dragons on the stamp represent masculine energy and power. An inscription reads: “Treasure of the imperial brush of Qianlong.” Known as a talented poet and calligrapher, the emperor used the seal to sign his works. During his reign, the empire doubled in size and the population rose to 400 million.

9 Scottish Jade Axes

In 2016, the National Museum of Scotland opened an exhibit featuring ancient jade axes. Dated to 4000 BC, the blades were over 100 years old when they arrived in Scotland. Experts have traced their origin to the Italian Alps. The manufacturing centers were located near the high mountains, and the jade was sourced from an elevation over 1,980 meters (6,500 ft). Archaeologists have located one of these jade quarries in Monte Viso, Italy, which dates back to 5200 BC. Over 1,600 jade axeheads have been recovered across Europe. Their ritual and spiritual significance remains unknown. Neolithic inhabitants of Northern Italy viewed the Alps as the home of the gods. It is likely they believed that rocks quarried from these sacred sites had the power to heal and protect. The axes may have been designed for rituals or sacrifice. The color may have had special significance, as copies were often made using locally available green stones.

8 Jade Burial Suits

In 1968, archaeologists discovered jade burial suits in the tomb of Prince Liu Sheng and his bride, Princess Duo Wan. Each head-to-toe outfit is composed of over 2,000 pieces of jade. The prince’s suit was sewn with gold thread. The princess’ suit used silver. These suits were rumored to exist since the fourth century AD. However, none had been confirmed until the tomb was excavated. So far, only 15 have been discovered. Experts believe that a master jadesmith took a decade to produce one suit. In AD 223, Emperor Wen of Wei banned the production of jade suits. He feared that they were irresistible to looters. Ancient Chinese believed that jade had extraordinary powers to both prevent decay and protect against malignant spirits. The prince and princess may have attained their goal of immortality. Jade is porous and may still contain their genetic material, which seeped in over two millennia.

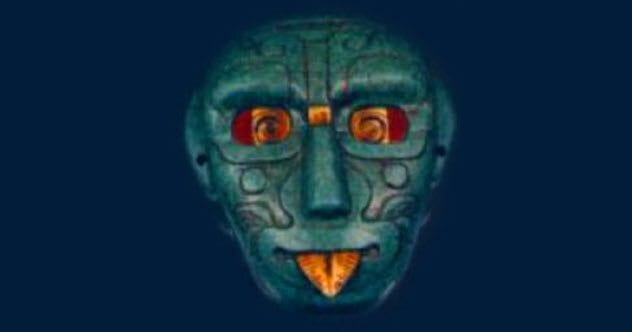

7 Mayan Shark-Toothed Sun God

In the jungles of northern Guatemala, archaeologists uncovered a mysterious jade mask at the Rio Azul Mayan site. The mask represents Kinich Ahau, the Sun god. He is depicted with one large shark tooth, which sheds light on Mayan spirituality, bogeymen, and hunting practice. Shark teeth are common finds at Mayan sites. They were used for everyday functions like weaponry, jewelry, and bloodletting tools. Coastal Maya were known to hunt sharks. They likely spread knowledge of the “sea monsters” and their teeth far inland. The tales were probably exaggerated as they were passed from trader to trader on their journeys from the coast. Like the Sun god’s mask, sharks in Mayan art are often portrayed with one large tooth. Archaeologists have uncovered Megalodon teeth at Mayan sites. It is possible that these remnants of gigantic prehistoric predators may have fueled the Mayan reverence for sharks.

6 Enigmatic Emirau Island Jade

Archaeologists discovered an enigmatic jade tool on Emirau Island off Papua New Guinea. Dated back 3,300 years, it was likely carved by the Lapita people. According to researchers, this ancient population spread from the western Pacific and are the ancestors of modern-day Polynesians. Jade tools are not uncommon in the region. However, this recent discovery is composed of a rare material, which archaeologists believe traveled with the Lapita from their homeland. The tool is jadeite, the hardest variety of jade. No examples of this tough rock have come from New Guinea. The only known contemporary sources, Japan and Korea, produce stone with a different composition. The closest chemical match came from jade in Baja California. Transoceanic travel is unlikely. An unpublished German manuscript from 1903 chronicling jade in Indonesia—less than 1,000 kilometers (600 mi) from the Emirau discovery—has led some to believe in an Indonesian origin. More tests are needed.

5 Jade Funeral Discs

Since 5000 BC, large jade discs have been placed on the bodies of deceased Chinese elites. Their function remains a mystery. Also known as bi discs, these nephrite carvings first appeared during the late Neolithic. The stones were frequently placed on the deceased’s chest or stomach. Many contain symbols related to the sky. Nearly all high-status tombs of the Hongshan culture (3800 BC to 2700 BC) and Liangzhu culture (3000 BC to 2000 BC) contain these discs. Given the lack of metal tools during the period, the stones were painstaking carved through brazing and polishing. The effort invested in their creation and their location in burials suggests deep spiritual significance. Some suggest that they are connected with specific gods. Others believe that they represent a wheel or the Sun, which symbolizes the cyclical nature of existence. The jade discs predate writing, and their function may never be completely understood.

4 Underwater Offering

In 2012, archaeologists recovered a mysterious jade object from Arroyo Pesquero in Mexico. Dated between 900 BC and 400 BC, the artifact may have been a sacrificial offering. It is carved from mottled brown and white jadeite, which is harder than steel. The 8.7-centimeter (3.4 in) by 2.5-centimeter (1 in) object was recovered 3 meters (10 ft) below the surface of a deep stream. The image is abstract, although most experts believe it is a corncob. The find dates back to the Olmec occupation of Veracruz. Their ancient city of La Venta, which housed up to 10,000 people and contained a 34-meter (112 ft) pyramid, was located a mere 16 kilometers (10 mi) from Arroyo Pesquero. Over the last 50 years, thousands of artifacts have been recovered from Arroyo Pesquero, leading experts to believe that it must have been a site for ritual offerings. The location is where freshwater and saltwater meet and likely had deep spiritual significance.

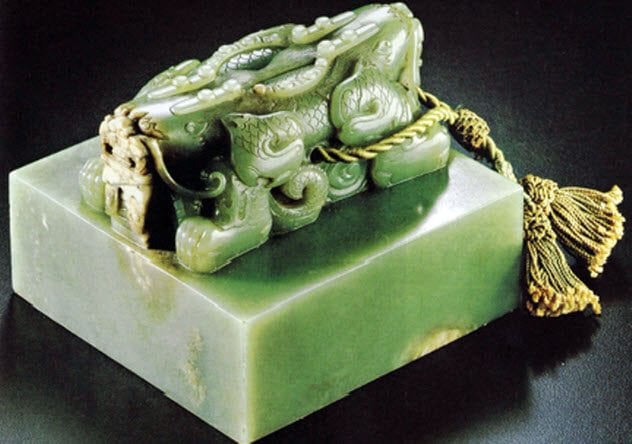

3 Heirloom Seal Of The Realm

The Heirloom Seal of the Realm is one of the most mysterious Chinese artifacts. According to legend, the jade was carved in 221 BC for Qin Shi Huang. In 221 BC, he united the six Warring States under the Qin dynasty. He ordered an imperial seal to be carved from the most fantastic piece of jade ever discovered. The seal passed from ruler to ruler as a symbol of imperial authority until it vanished around AD 900. The artifact was carved from the He Shi Bi jade, for which a man allegedly lost his legs. Some believe that it was actually stolen from the Zhao state. The seal was an embodiment of the mandate of Heaven, and possession was enough to consider a regime “historically legitimate.” Why the seal disappeared remains a mystery. Some theorize that later emperors were obsessed with hoarding seals to reduce the significance of the Heirloom Seal.

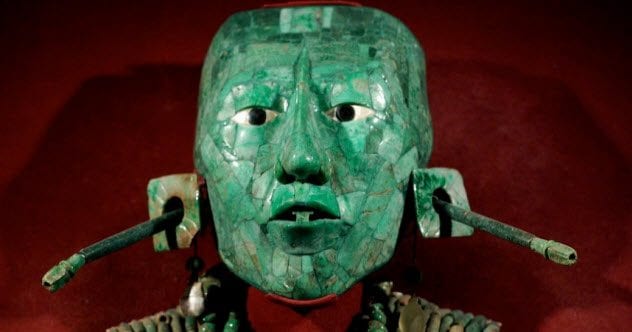

2 Lord Pakal’s Funeral Mask

In 1952, while excavating the funerary crypt of the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque, archaeologists unearthed the mosaic burial mask of Lord Pakal the Great. Dated to the Mayan Late Classic period around AD 683, the mask is composed of a mosaic of 300 tiles of jadeite, albite, kosmochlor, and veined quartz. The eyes are made of conch shell and obsidian. A wooden backing originally held the pieces together, and the mask was attached to the deceased king’s face with a layer of stucco. On Christmas Eve 1984, Pakal’s mask was stolen along with other treasures from Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Anthropologia. A pair of vet school dropouts conducted the heist by entering the museum via air ducts. In 1989, a drug trafficker turned stool pigeon and brought down the art thieves. They had tried to exchange the artifacts for cocaine. Pakal’s mask and the other artifacts were returned in good condition.

1 Liangzhu’s Mysterious Cong

The Neolithic Liangzhu culture contained master jade craftsmen who lived along the Yangtze River Delta in modern-day Zhejiang province. Over the years, 50 sites attributed to the Liangzhu have been excavated. Tombs of their elites invariably contain elegantly crafted cong. These are square tubes of jade containing a circular hole. There are single-section varieties and longer ones. Often, the square corners are covered with face-like designs, believed to be protective spirits. Speculation about the cong’s function can be traced to the Qing dynasty. Their ubiquity in elite burials offers tantalizing suggestions. They were likely symbols of power. Jade continued to be buried with the dead until well into the Han dynasty (206 BC to AD 220). Some suggest that the objects provided a road map for the dead on their journey into the next life. Others propose that there was a belief that jade may have prevented the decomposition of flesh. Abraham Rinquist is the executive director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.