But you didn’t load this page for a highlight reel of this era. We’re here to clear up some misconceptions that a cursory education about the period may have produced. In the process, we may bring Napoleon Bonaparte down a peg in several ways. It’s an effort which is long overdue.

10 Napoleon Was The Best French General Of The Era

Even among nations that felt the wrath of Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies and despite the fact that he died a prisoner in exile on a small island in the southern Atlantic Ocean, his enduring legacy is as one of history’s greatest commanders. It allowed for his imprisonment and death years later to have an aura of tragedy even though wars for his glory left roughly one million French soldiers dead. The best French general of the era was almost without question Louis-Nicholas Davout, the youngest field marshal in Napoleon’s army (a year younger than Napoleon himself). He was instrumental in saving the day for Napoleon Bonaparte at the 1805 Battle of Austerlitz by moving his two divisions 120 kilometers (75 mi) in two days and holding strong against overwhelming numbers while Napoleon attacked the enemy center. Davout prevented defeat at the 1807 Battle of Eylau and also won the day by attacking the Austrian flank at Wagram in 1809. He organized the army that Napoleon would use to invade Russia in 1812. When things turned against the French, Davout commanded the rear guard defense and allowed Napoleon to escape.[1] Napoleon’s loss at Waterloo was in no small part attributed to the fact that Bonaparte, ever a glory hog, didn’t bring Davout and his forces with him. But when commanding independently, Davout’s record was even better: He never lost a battle. This was most impressive at the Battle of Auerstadt, where he was outnumbered more than two to one, longer odds than Napoleon ever faced. Still, Davout won the day. But Davout was no saint. In 1814, his army was trapped at Hamburg and sieged through the winter. With no alternative but surrender as supplies dwindled, Davout evicted tens of thousands of desperate civilians from the city. At best, it was a ruthless action. But Davout never demonstrated much love for anything but France itself.

9 The French Army Was The Best It Has Ever Been

The reputation acquired by the French military in World War II and their unwillingness to take part in the 2003 invasion of Iraq left many people thinking that the time under Napoleon Bonaparte was France’s last hurrah. The troops must have been the most capable to win battles all the way from Barcelona to deep in Russia. They could move at great speeds and stood their ground against long odds. But training among the French infantry could be extremely lax. It would get so bad that it could become lethal. The Time-Life book The Enterprise of War cites Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, Marshal of France, estimating that roughly 25 percent of the casualties among the French infantry were poorly trained soldiers shooting each other. Even Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe series never would have portrayed them as so inept. It was also a time of particularly disgraceful conduct during the frequent periods that French armies spent in enemy territory. To free Napoleon’s army from the burden of supply wagons, French troops were instructed to “live off the land.” In practice, this meant that the army would pillage and rape almost as a matter of policy in a manner that could make Vikings look timid.[2] Not that Bonaparte would likely have minded as it was recorded that he raped his Polish mistress the first time he had sex with her. Incidentally, Davout was noted as an exception to the plunder rule, and his corps enforced the death penalty for pillaging. Davout himself didn’t see any profit from plunder, which no doubt helped alienate him from his peers like a clean cop in a dirty department.

8 Napoleon Started Off Effectively Unbeatable

According to the narrative that’s generally pushed, Napoleon could outwit his divided and conquered enemies without exception early in his career. Toward the end, he started to get overconfident, he lost the youthful energy that had him mailing hundreds or thousands of letters a day, and his enemies learned his strategies through trial and error. After all, his most famous losses (the Russian invasion and Waterloo) were within the last quarter of his career. Considering that he said of his career, “I have fought 60 battles and I have learned nothing,” he obviously thought of himself as a perennial wunderkind. Yet Europe and Asia didn’t need to wait for the duke of Wellington or Russian guile to see Napoleon get outfought. Few amateur historians have heard of Joseph Alvinczy. But on November 11 and 12, 1796, he became the first general to defeat Napoleon. This is especially impressive considering that Alvinczy started the Battle of Caldiero at a significant numerical disadvantage. While Bonaparte’s army would recover from that and ultimately win the war, the same could not be said when Napoleon was defeated at the Siege of Acre in 1799, which ended his Egyptian campaign in disaster. Just a year later at the decisive Battle of Marengo during a war with Austria, Napoleon Bonaparte’s initial battle plan ended in defeat and he planned to retreat. It wasn’t until he received encouragement and advice from General Louis Desaix on how to turn the enemy’s flank (“This battle is lost, but there is time to win another one,” said Desaix shortly before being killed in action during the same battle) that Napoleon turned the tide in his favor.[3] Let this further serve to illustrate how exceptional Field Marshal Davout’s career was.

7 The Louisiana Purchase

This 1803 transaction doubled the size of the United States at a seemingly low cost ($15 million). So it’s often portrayed as Napoleon Bonaparte shortsightedly selling off vast amounts of valuable territory because he couldn’t see how much it would soon be worth. This is reinforced when you learn that the American government was ready to spend up to $10 million on New Orleans and West Florida alone.[4] However, at the time, it made sense for France to do this for other reasons. For one thing, France had just lost control of Haiti to a slave revolt and yellow fever, which made supplying their North American forces all the more difficult. For another, France had demanded the payment be entirely in gold and paid up-front, filling France’s coffers at the perfect time for an upcoming war with Britain (and eventually, an alliance of Austria, Russia, and Prussia). It was also a huge cost for America that required them to go deeply into debt (to, of all countries, Great Britain).

6 French Wore Blue, British Wore Red

People from the US are used to portrayals of the armies in these respective colors. We imagine the British in red coats because it supposedly made them easy targets for the colonial soldiers and because American uniforms provided by the French during the Revolutionary War were blue. However, there was quite a rainbow of colors for uniforms on both sides.[5] On the French side, many Dutch Grenadiers wore white uniforms and dragoon cavalry (essentially infantry who rode to battle but then dismounted to fight) wore green uniforms. Napoleon’s armies even had Mamluk cavalry from the Middle East who wore turbans and favored red vests. After Napoleon defeated Prussia and granted Poland independence, La Grande Armee also had Polish troops with uniforms that were largely purple. In contrast, the British units included rifle regiments that dressed in seemingly sensible green uniforms or hussar cavalry that wore blue. Frankly, sticking with red and blue uniforms seems like it would have greatly simplified things.

5 It Was A Highlight For France As A Nation

Historians and students with a taste for wartime history will consider the times when a nation is defeating its neighbors as among the best. Whatever the ethics, at least it will provide wealth and land for the citizens of that nation through plunder. And to his credit, Bonaparte undertook some humanitarian programs both between his campaigns and at the height of them. Surely, he deserves credit for freeing Jews from ghetto communities. The ugly truth at the time? Throughout Napoleon’s reign, poverty was rife. His 1806 decree for an embargo on British imports, which was called the Continental System, caused obvious harm to France and its allies. Even an egomaniac like Napoleon could see it. So, in 1810, he began writing concessions into it. Napoleon also stained France’s legacy in 1802 when he reinstituted slavery (after it had been banned in 1794).[6] The loss of Haiti in 1803 as a result was not a coincidence. Aware of the lack of good he did for the common people, Napoleon said, “I found them—and I left them—poor.”

4 Russians Deliberately Defeated Napoleon By Retreating Until Winter

To put the Russian strategy for the 1812 invasion of Russia in a positive light, the notion was put forward that the Russian military had hit upon a plan of falling back when Napoleon invaded with 600,000 soldiers. The Russians knew that even a huge army would stretch itself thin by occupying such a vast country. Then, when Napoleon took the capital, the Russians burned it down and forced him to retreat through winter, devastating what had been the largest army in European history through sheer guile. According to a historical review by Vincent J. Esposito and John R. Elting for A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, the communications among the high command of the Russian military didn’t show so much as “a trace of a plan” to wear La Grande Armee down through planned retreats.[7] This is further borne out by prolonged resistance at cities such as Smolensk (at a cost of more than 12,000 casualties), which is not the sort of action performed by an army that is engaging in a delay strategy.

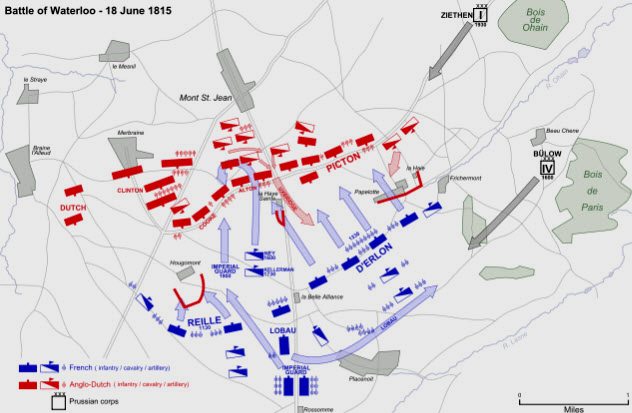

3 Waterloo Mattered

It’s by far the single most famous battle of the Napoleonic Wars, if only because its name became a slang term for the defeat of a person with hubris. The Battle of Waterloo was a confrontation between the emperor and the duke of Wellington, the hero of the Peninsular War and one of the most successful generals in British history (even though he hated war). Waterloo even had a level of drama surrounding it for being “the nearest-run thing you ever saw” as the duke put it. Yet Napoleon wouldn’t have been in a tenable position if he had won. As mentioned before, Napoleon’s wars had already severely strained France’s economy, so his nation was in no mood to commit to a prolonged war. Even as he seemed to have victory within his grasp on June 18, 1815, overwhelming numbers of Austrian, Russian, and Prussian troops were gathering against him. Sheer superior numbers had already defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 and in the 1814 campaign that had ousted him. As Owen Connelly had made clear in his book Blundering to Glory, Waterloo was full of sound and fury but it signified nothing.[8]

2 The Invasion Of Russia Was Napoleon’s Downfall

To portray the defeat of Napoleon’s empire as the result of hubris instead of an inevitability under the circumstances, his 1812 invasion of Russia is often pinpointed as the decision that ruined him. Makes sense because it cost the French alliance hundreds of thousands of soldiers and showed just how defeatable their armies really were. Later, on Saint Helena, even Napoleon claimed that he would have become master of Russia shortly after the return of good weather if Moscow hadn’t burned. But this is inaccurate for an array of reasons. First, despite Napoleon’s famous affinity for gunpowder, France’s ports were blockaded as soon as the country committed to war with Britain. This had the dire effect of leaving Napoleon’s empire short on the saltpeter needed to make gunpowder. No wonder the French soldiers were such bad shots. There wasn’t enough powder for them to train properly. Every power that has dominated the European continent but could not properly challenge Britain on the high seas has lost—hence the Allies winning both World War I and World War II. In addition, Napoleon’s Continental System, his only available means of combating this, was unenforceable. Even if there hadn’t been such open hostility to the French, a lot of bribery and smuggling kept British merchants afloat just so Prussia, Russia, and others could keep their economies going. Even as it was, Austria’s armies (without support from Prussia or Russia) defeated Napoleon at Aspern-Essling in 1809.[9] So, it was merely a matter of the allied rivals adapting to Napoleon’s tactics. This would defeat him on the battlefield and eventually drive him from power.

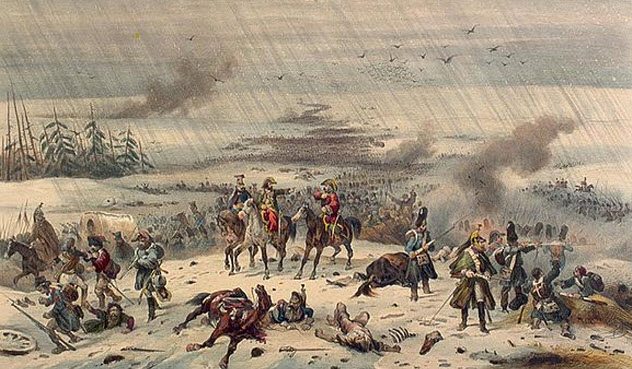

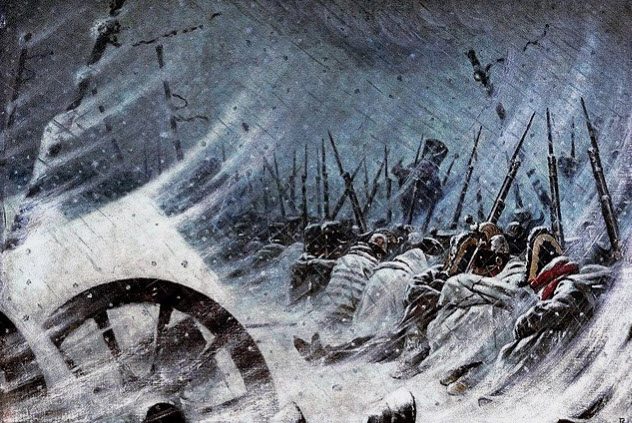

1 Russian Winter Defeated Napoleon

As we said earlier, history remembers the Russian winter as the thing that broke the back of Napoleon’s 600,000-strong army. Another theory emerged that the frigid winter caused the tin buttons on the uniforms of many French soldiers to crumble. With their uniforms unbuttoned, many soldiers would have died in those harsh weather conditions. However, the worst damage had already been inflicted on the invasion force before autumn, long before the winter winds began to blow. In June 1812, Napoleon’s vast army was moving through Poland, which had been devastated by the Russian army shortly before the French arrived. Soon, tens of thousands of horses were dying from lack of proper feed. Then typhus struck the French army. By the end of July, it had sickened or outright killed 80,000 soldiers, more than the army would lose after its retreat from Moscow.[10] Under such conditions, desertions were understandably widespread, particularly among the units that were only fighting because their king was allied with their hated conqueror. By this time, Napoleon’s army had lost about half its strength. Disease and desertion continued to weaken the army throughout late summer. When Napoleon went into Moscow, he only had about 90,000 to 100,000 men left. (Although sources differ on the actual number of soldiers, they agree that his army was decimated.) His forces had lost about 80 percent of their original strength. It must be said that the epidemic was a particularly strong case of karma in a sense. La Grande Armee’s habit of living off plundered peasants had severely exposed the soldiers to typhus from Polish peasants in devastated communities. Even though Napoleon was beloved in Poland for providing the nation with its independence, his tactics there did at least as much to bring him down as his hubris did. Dustin and Adam Koski wrote the dark fantasy book Not Meant to Know.