10 Filippo Lippi And Lucrezia Buti

There’s not too much about the life of Filippo Lippi that isn’t filled with the details of a modern-day reality show star. Considering that he was first forced into the restrictive life of a monk, we may at least sort of understand why he was so rebellious. Born around 1406 and orphaned as a child, he and his brother were given to the care of a Carmelite monastery. Raised in the monastic environment, he took his vows in 1421. His education is thought to have included painting, which he showed a natural talent for. By the 1450s, he was a well-known artist throughout Florence and fell into favor with the Medici family. Tasked with painting an altarpiece in a convent just outside Florence, Lippi not only met and became absolutely infatuated with a novice nun named Lucrezia Buti, but he convinced her to join him in the more secular world. They quickly moved in together and ultimately had two children. The nuns that had been tasked with keeping an eye on her were disgraced, and according to the story, her father never smiled again. As if the idea of a monk running off with a nun wasn’t lurid enough, Lippi continued painting—and he used his nun wife as the model for the Virgin Mary in at least one of his works. What we know about Lippi suggests that the trouble didn’t stop when he fell in love. There are records in Florence of summons issued when it was discovered that Lippi wasn’t just living with Buti, but that the household also included six other women in addition to her. He was also hounded by more secular complaints, with patrons claiming that he never finished commissioned works. At one point, even the powerful Medici family was forced to arrest him and confine him to their palace to force him to finish what they’d paid him for. Claims that he wasn’t paying employees piled up (he was at the head of two major art studios), and before he was given a papal leave from his monastic vows (ultimately marrying Buti), he was put on the rack and tortured.

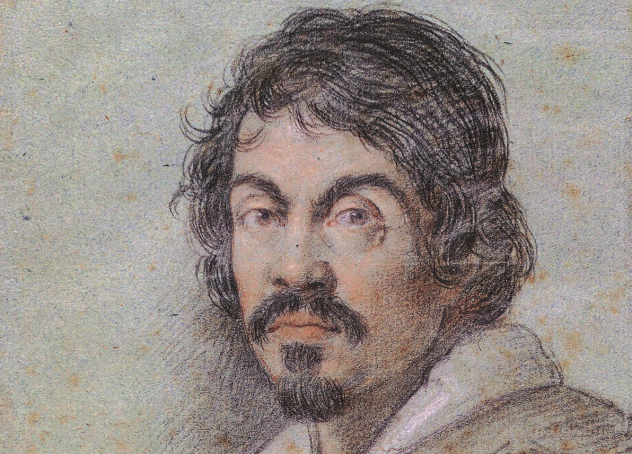

9 Caravaggio And The Knights Of Malta

Caravaggio may have murdered a man in Rome, but that was just the start of his problems. After Caravaggio fled Rome, he ultimately ended up on the island of Malta. Just what happened between the already well-known, troublemaking artist and the Knights of Malta is still up for debate, with most of it pieced together from fragments of sometimes cryptic documents. It’s generally thought there was some kind of family connection between Caravaggio and the knights for them to accept him in their company, although the order had given sanctuary to artists on the run from certain circumstances before. Only a few months after Caravaggio arrived on Malta in 1607, the head of the order wrote the Pope to secure a pardon for him, stating that he was a pretty decent guy, except for that one murder, and they really wanted him to be a member of the order, if only the Pope could get rid of that unfortunate cloud of persecution that was following him. A papal waiver was issued, and Caravaggio was inducted into the order. His acceptance was fairly short-lived. It wasn’t long before he was jailed over what was called an “inopportune quarrel” with one of the other knights, which resulted in the man’s house being broken into and a subsequent stabbing. Caravaggio was imprisoned but, somehow, managed to escape both the prison and the island. Expelled from the Order, most specifically for leaving the island without permission, Caravaggio started wandering and died about two years later. His death has long been the stuff of mystery. It has been suggested that it was far from a natural death; it was an assassination that was ordered by the Vatican and carried out by the Knights of Malta whom he had so offended. In 2010, remains discovered in Tuscany and confirmed (with a likelihood of 85 percent) to be the bones of Caravaggio suggest that it was prolonged exposure to lead paints (along with infected wounds that he’d sustained in a later attack that left him disfigured) that ultimately led to the early death of the artist.

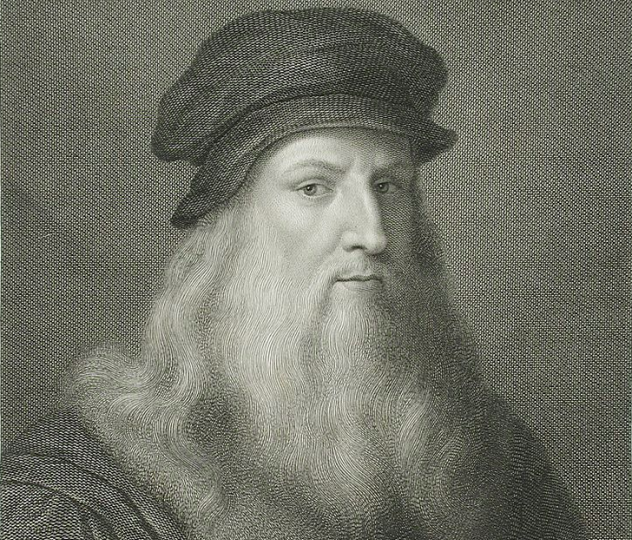

8 Leonardo Da Vinci And Jacopo Saltarelli

Being gay in 15th-century Italy was a bad, bad thing, and it wasn’t helped any by the release of Dante’s Inferno and Sandro Botticelli’s illustrations of the torments that waited for the homosexual sinners in the seventh circle of Hell. It was such a big deal that in 1432, Florence established a special organization that would patrol the streets at night, looking for gay activities and arresting the participants. They were called the Officers of the Night and Preservers of Morality in the Monasteries, and they took their job seriously. Officially, an arrest could lead to being burned at the stake, but a fine or shackling in the stocks was more common. Leonardo da Vinci was arrested in 1476, after his name showed up on a piece of paper that had been left—anonymously—in one of the city’s ominously named “holes of truth,” meant for leaving tips that would lead authorities to any wrongdoers. Da Vinci, along with three others, was accused of having had sexual relations with a 17-year-old named Jacopo Saltarelli. Charges were filed against all four of the accused, but nothing ever came of it, and the charges were ultimately dropped. There was no supporting evidence, although the whole incident kicked off a scandal that has followed da Vinci ever since. Historians throughout the centuries have found sometimes bizarre evidence indicating that his perpetual bachelor state meant that he was gay. One such piece of evidence is the idea that he left a lot of his works unfinished. Clearly, that’s the sign of a gay man.

7 Andrea Del Sarto And The Mistress Madonna

When Andrea del Sarto unveiled his Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist, it was to rather shocked whispers and the spread of hushed rumors. Those rumors suggested that the model for one of the holiest of all women was none other than del Sarto’s mistress, Lucrezia del Fede. Del Fede wasn’t just his mistress, she was a horrible, horrible person. She was characterized pretty clearly by Giorgio Vasari, the era’s most prolific biographer of the great Renaissance artists. According to him, she was low-born, which was, in itself, not a bad thing, but she was also haughty, arrogant, vain, and absolutely nothing less than a bully. She visited del Sarto’s apprentices with nothing but grief, and the friends that he had once been close to no longer wanted to have anything to do with him. There was also the questionable time frame of their relationship. Del Fede was still married when she began seeing the painter, but her husband quite conveniently died from some sudden, unidentified illness, freeing her to marry del Sarto. At the time, he was so famous that he had been given some of the highest titles awarded to artists, and he was even summoned to France by Francis I. In other words, he was quite a catch and quite a step up from the hatmaker to whom she had been married. The stories about just what kind of person she was are seemingly endless. Del Sarto’s work for the king of France was cut short when he returned to Florence and to her, taking with him the money that the king had entrusted to him to buy more pieces of art. It’s been suggested that he returned to Italy only at her bidding, when she convinced him to buy them a house and never return to France. She ultimately outlived him by about 40 years, and it’s also thought that she couldn’t truly be bothered to care for him and abandoned him when he was dying. How many of the accusations were true and how many were based in her consistently poor treatment of her husband’s apprentices—and of the biographer Vasari—is uncertain. The story was the inspiration behind Robert Browning’s poem “Andrea del Sarto,” where Browning attempts to create a love-is-blind sort of scenario for the two.

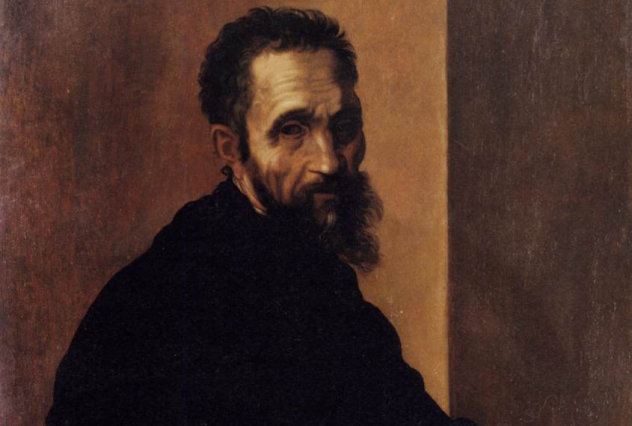

6 Michelangelo’s Cupid

Near the end of the 15th century, Michelangelo decided to leave Florence for Rome to see where his career would take him. According to the story written by Michelangelo’s friend, Ascanio Condivi, his first trip to Rome was guided by a minor member of the Medici family, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco. After seeing a marble statue of Cupid that the young Michelangelo had done, he suggested that with a little aging, it was good enough to pass for an ancient antique, which it did. The statue was ultimately sold to a Cardinal Raffaele, and, finding out that it wasn’t an antique after all, he sent someone to track down the artist and invite him back to Rome. Fortunately, it wasn’t an ominous as it sounds, because Michelangelo went and found that his skills were suddenly in demand in Rome. His introduction to Roman society was based on not only his talents, but his ability to create something that would pass for one of the great works of ancient Greece. Not long after he arrived there, the statue was on sale again, and again, it was being advertised as an antique. Somewhat ironically, the controversy over whether or not it was an antique allowed the interested Duchess of Mantua to offer a much lower price for the statue and to buy it at that low price. According to Thierry Lenain, art historian from the Institut Francais in London, Michelangelo also wasn’t above forging other things—like paintings. And he did it, the historian says, so he could keep the originals. The view of the time was that he wasn’t necessarily doing it for the art’s sake but was doing it for the originals. Whether or not that’s true, it certainly hasn’t stopped the claims. One of the most recent works claimed to be a Michelangelo forgery is the statue of Laocoon, originally discovered in 1506, when Michelangelo was working on the Pope’s tomb. In spite of being most commonly attributed to three classical Greek sculptors, that hasn’t stopped rumors from circulating that it was actually Michelangelo’s work (although it’s doubtful).

5 Aleco Dossena

Having done most of his work in the 1920s, Dossena isn’t technically a Renaissance artist, but the idea that technicalities never stopped him is why we’re mentioning him. Those who watched him sculpt, working with marble as though it was second nature, have said that he was most certainly the reincarnation of a Renaissance artist. Others thought so, too. According to the most prolific story, Dossena was in Rome during World War I. It was there that he met a rather shady dealer named Fasoli. Dossena had already honed his talents in spite of being kicked out of school. He had been carrying a terracotta bas-relief of the Madonna and Child, which he was looking to sell to make some extra cash for Christmas. Fasoli was thrilled to find out that Dossena wasn’t the thief they originally thought, but he was a forger with incredible talent. Beginning in 1918, Fasoli set Dossena up in a shop and had him cranking out Renaissance replicas. With the backing of a blossoming black market, it’s estimated that the fakes sold for around $2 million over the next decade. His works ended up in private collections, as well as museums like the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and even the Metropolitan Museum of Art, all sold as originals. Many fooled some of the field’s top experts. And Dossena did it all from photographs and from live models, creating a weird sort of combination artwork. In some cases, it was said that comparing a work from Dossena with the original was like two masters having captured the same subject at slightly different times. In interviews, he stated that he had never intended to create fakes; all his works were original, and originally his, created from his observations and done in the style of antiques. The whole thing came to a crashing halt after 10 years of sales. Fasoli, in desperate need of cash to pay the funeral expenses for his mistress, refused to pay Dossena. Dossena then hired a lawyer, saying that it was only then that he realized the scale of what had been going on. Court cases dragged out, museums realized what they really had, and the prices that his work fetched fell through the floor. He died in 1937, unrepentant and not at all modest.

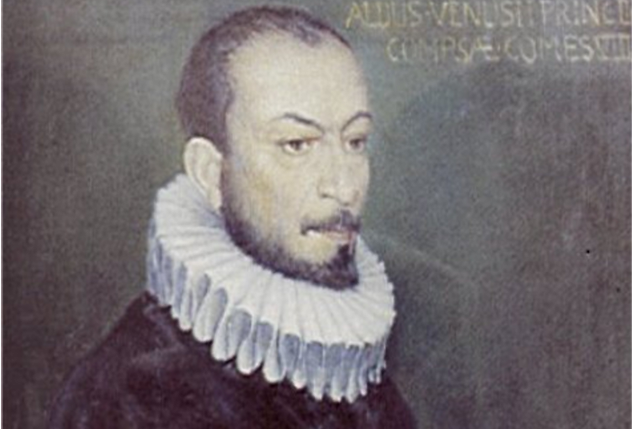

4 Carlo Gesualdo

Don Carlo Gesualdo, composer and the Prince of Venosa, murdered his wife and her lover on October 16, 1590. The details are understandably gruesome, and the fallout was downright bizarre. First cousins, they married when he was 20 and she was 24. This was her third marriage; her other two husbands had already died “in excess of connubial bliss.” So, needless to say, perhaps the idea that Gesualdo found her cheating on him wasn’t entirely surprising. That it was the Duke of Andria—and that he was wearing one of her silk nightgowns at the time—is a little more surprising. The damage that was done by the livid prince is something between history and myth. According to the official crime scene reports, the Duke had been shot at least once, and both had been stabbed many, many times. And there was no doubt as to who had done it, either. According to eyewitness testimonies, Gesualdo stormed into the apartment, shouting, “Kill that scoundrel, along with this harlot!” A bit later, he walked back out, covered in blood. After thinking a moment, he expressed his doubt that they were really, truly dead and went back into his apartments to do some more damage. The murders weren’t just horrific; they launched a whole series of rather bizarre rumors. According to the stories that started circulating through Naples, the composer did everything from dumping the bodies outside and leaving them to rot, to mutilating them further, to letting an insane monk have his way with his wife’s body, to killing a child he suspected to be the product of their affair. Whatever he really did to them, he would never be charged with any crime. He was a prince, after all, and at the time, they were above the law. His music would be hailed as some of the most inventive, groundbreaking music written throughout the entire Renaissance. At the same time he’s long been painted as a sort of real-life Dracula.

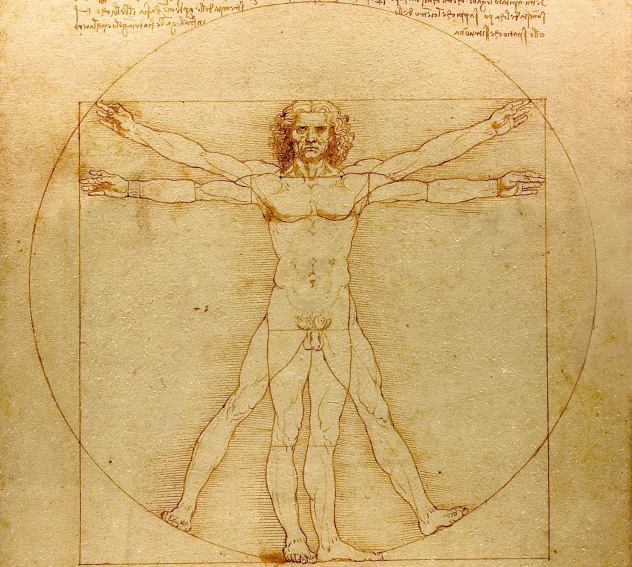

3 Leonardo Da Vinci, Giacomo Andrea, And The Vitruvian Man

By now, the sketch of the Vitruvian Man is so commonplace that when we see it, we tend not to even look twice at it. It’s a man inside both a circle and a square, and our reaction to it today doesn’t really do it justice. The idea that man would fit inside both shapes is one that goes back to antiquity, and it has more meaning than simply being a neat geometric trick. It was thought that the circle was our representation of the divine, while the square was our symbol for the secular. The idea that they could both be combined with man in the center was to combine the heavenly and the earthly and to be able to show that man had been made in the image of both. It was an idea set forth first by the writer Vitruvius, hence the figure’s name. Da Vinci is the one that’s credited with being the first to illustrate the ancient idea in a way that’s anatomically correct. While there’s no doubt that he did have unprecedented knowledge of human anatomy, we now think that he didn’t so much come up with the idea on his own but swiped it from one of his contemporaries. Making man fit inside both shapes was, for a long time, a lot more complicated than we think of today. The original writings that specified what the image would look like also had a set of guidelines. For example, the man’s navel should be at the center of the image. People had tried and failed to produce the image as it was described, until da Vinci made the geometric shapes off-center. It wasn’t his idea, though. Renaissance researcher Claudio Sgarbi has recently uncovered an earlier drawing by an architect named Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara that provides the answer to the pictographic riddle. Giacomo Andrea’s version of the drawing is full of corrections, as if he were messing about with the idea before hitting on the right answer. He and da Vinci knew each other, and we even know that they had dinner together around the time da Vinci drew his version. We only have hints about who Giacomo Andrea really was, and he seems to be quite literally revolutionary. At the time, the French were occupying Milan. Da Vinci was on friendly terms with them, but Giacomo Andrea was, apparently, something of a guerrilla fighter against the occupiers. He was eventually arrested, hanged, quartered, and wiped from the history books.

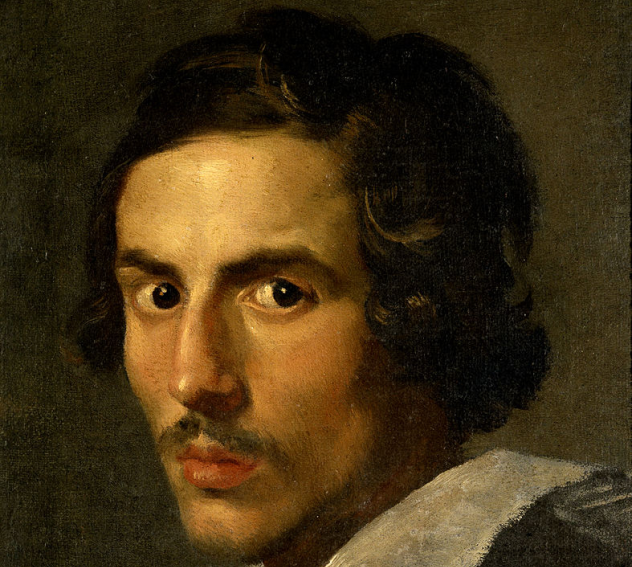

2 Bernini, His Brother, And Their Lover

Gianlorenzo Bernini was the lynchpin between the Renaissance and the Baroque, taking all the elegance of the Renaissance greats and adding more movement and passion. First appearing in front of Pope Paul V when he was only eight years old, he made such an impression on the man that he was instantly installed in Rome with a mentor and teacher. Bernini’s place of honor among artists meant that he was ultimately able to get away with some pretty heinous things. By the time he was 40, he was well-established with his own commissions from the Pope (now Urban VIII), his own studio, and his own set of assistants. One of those assistants was Matteo Bonarelli, who had a wife, Costanza. Costanza was the subject of a portrait bust that’s very clearly done by a man obsessed with her, which gives away quite a bit about their relationship. Bernini took her as his mistress, but if there’s one thing we know about people who cheat, it’s that they’ll likely do it again. It wasn’t long before Bernini found out that she had another lover—his own brother, Luigi. A confrontation left Luigi with a few broken ribs, which wasn’t bad, considering that Bernini was making every effort to kill him with an iron bar. Luigi fled to the safety of a church, and while Bernini kept after him, he ordered one of his servants to go and find Costanza. The man found her—and sliced up her face with a razor. The Pope intervened. Luigi was banished, and the servant was arrested, tried, and sent to jail. Costanza was also arrested, charged with adultery, found guilty, and imprisoned. Bernini, on the other hand, was awarded a new wife, said to be one of the most beautiful women in Rome, who would ultimately give him 11 children.

1 Raphael, The Baker’s Daughter, And Death By Sex

First called a master when he was only 15 years old, there’s no denying that Raffaello di Giovanni Santi packed a lot of living into only a few decades. Dying on his 37th birthday from a cause that’s alternately considered either a fever or what biographer Vasari called “amatory excess,” he’s another Renaissance painter who has led historians on a wild chase through secrets left in his paintings and some scattered records in order to piece together what really might have happened to him. Margherita Luti, also known as La Fornarina, is the lover that’s usually associated with the artist’s early death. It’s rumored that he was so in love with her that he was unable to complete commissions until she was moved nearer to him. According to a cryptic discovery made while cleaning one of Raphael’s portraits of her, it’s thought that he might have been in a bit of a quandary. In 1520, Raphael painted a semi-nude portrait of her, which already seemed to firmly establish their relationship. In the portrait, she has a ribbon tied around her arm, signed with his name. When the portrait was cleaned, though, it was found that she was also wearing a ring—a rather expensive-looking, square-cut ruby that would have been well above what a baker’s daughter or a courtesan would normally be seen wearing. At some point, the ring had been painted over, detected only 500 years after it was quite deliberately hidden. Now, it’s thought that the two were actually engaged, but the problem is that Raphael was also engaged to someone else. He reportedly kept putting off his official wedding to a woman named Maria Bibbiena, who just happened to be the niece of a cardinal—and Raphael’s patron. There are few things that might have ruined him quite like ditching a woman of such standing as Maria for someone like La Fornarina, but the presence of a ring on her finger in the portrait suggests that it might have been what he was considering doing, if he hadn’t done it already. He’d also already made some long-term plans for her, bequeathing enough to her in his will that she was quite comfortable after his unexpected and untimely death. Read More: Twitter