10Center For Strategic Counterterrorism Communications

A team of about 50 based within the State Department, the CSCC was formed in response to Al Hayat Media, the English language media outlet of ISIS. The “Cadillac of terrorist propaganda” produces a staggering amount of high-quality videos that neatly package their recruiting message, and before the CSCC formed in 2010, nobody was doing anything to refute that message. The team produces their own videos, tweets, blogs, and Facebook posts aimed at “blunting the recruitment pitches online” and causing potential terrorists to rethink their options. It has been difficult to tell just how effective the campaign has been. But since 2013, multiple Twitter accounts have popped up trying to counter the CSCC’s counter-message, which would indicate that they’re a big enough thorn in the side of terrorist recruiters to be deemed at least somewhat effective.

9Operation Earnest Voice

A far more complex social media manipulation effort under the control of the US Central Command (Centcom), the innocuously named Operation Earnest Voice began during the initial conflict with Al-Qaeda, using undercover operatives to blend into foreign social networks and spread pro-American messages. In 2011, a $2.76-million-dollar contract was awarded to a California company to help OEV greatly expand its campaigns. The company was tasked with creating “sock puppet” software, which enables a single user to control 10 fake social media accounts, appearing to be located all over the world. The users actively monitor online discussions and jump in to try to counter anti-American sentiment. While it was asserted that the software would not be used domestically as it would have been in violation of US law at the time, that is no longer the case (more on that later), and Centcom has not spoken publicly about it since.

8Project Pedro

Conceived and implemented during the Eisenhower administration, the offensively named Project Pedro was an effort to make sure that Mexico was on the right side of the Cold War, with polls showing close to three-quarters of Mexican citizens neutral on Communism. It was fairly simple: Mexican businessmen were paid to act as fronts for US-owned companies that produced newsreels, which were popular in Mexican theaters. These US-produced newsreels made it into almost 400 theaters and blended pro-US propaganda and advertising (for companies like Goodyear and Pepsi) with more traditional Mexican newsreel fare like reports on recent bullfighting and boxing matches. The project continued throughout the 1950s but was terminated in the early ’60s, as it was expensive, and its efficacy had proven impossible to determine.

7Shared Values Initiative

Shortly after 9/11, the US government was actively seeking ways to improve its image with Muslim communities overseas. As the meat of this effort, the Shared Values Initiative tried to do this in perhaps the most American way possible: with a glossy, expensive television advertising blitz showcasing happy, safe, and proud Muslim Americans extolling the virtues of their adopted country. The campaign severely misjudged its audience and was a catastrophe. Many leaders of targeted countries refused to cooperate, and even a senior member of the US Council on Foreign Relations called it “extremely poor . . . it was like this in the 1930s and the government was running commercials showing happy blacks in America.” The program was canceled in 2003, having spent only about half of its budget.

6ZunZuneo

ZunZuneo was the “Cuban Twitter,” a text message–based social network that gained 40,000 subscribers between 2010 and 2012. It was marketed to young Cubans and focused on such non-controversial topics as soccer and movies, and none of the network’s subscribers ever had any idea that it was designed, deployed, and operated by the US government. The company was set up through an elaborate network of front corporations and even had phony ad banners, making it look like a commercial enterprise. When enough subscribers had been gained and an opportune moment arose, the network would introduce political content to stir unrest, eventually being used to organize mobs and protests, triggering a “Cuban Spring” and perhaps even a revolution. Although the project has since come under scrutiny because of questions about its legality, it was discontinued for a mundane reason—the grant that provided its funding expired.

5The Border Patrol’s ‘Migra Corridos’

In another program aimed at the Mexican citizenry (albeit for a very different reason), the Homeland Security Agency enlisted the Border Patrol for help in disseminating propaganda of a very peculiar type. “Corridos,” folk ballads, have long been ingrained in Mexican culture, and the HSA produced an album of them, describing the hardships and horrors that await if one should attempt to immigrate to America illegally. The Border Patrol purchased airtime on both radio and television and released a CD entitled Migracorridos (“Migration Ballads,” roughly translated). The 2005 campaign fell under suspicion by the populace, many of whom thought their own government was responsible. The Border Patrol cited a decrease in migrant deaths (from 492 to 390) in the year after the CD’s release as proof of its success, though myriad other factors could explain this.

4America’s Army Game Series

As previously alluded to, the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act explicitly prohibited the use of propaganda by the United States domestically. This never prevented the government from finding loopholes, such as financing the Ad Council—creators of decades’ worth of ubiquitous PSAs, some with questionable content—or releasing extremely thinly disguised propaganda that acknowledges its source, such as the America’s Army video game series. First released in 2002, the online, free-to-play game is a first-person shooter built on Epic Games’ Unreal Engine, the single most popular first-person game engine of all time. It plays much like any first person shooter, except nobody dies (opposing players are “neutralized” and no blood is shown). In the first 10 years of its release, the Army spent over $30 million developing the series.

3Video News Releases

If you are ever watching a news broadcast that has an unclear or unfamiliar station affiliation, you may be watching what in the industry is called a VNR or Video News Release. These are segments that are sold in packages to television stations and affiliates and are made to look like actual news segments. Some are produced by ad agencies or public relations firms to subtly market products, and some are produced by government agencies to subtly influence opinion. Since a New York Times expose in 2005, the Federal Communications Commission has been investigating the practice. Press officers for several federal agencies have long maintained that the segments are neutral and factual, amounting to nothing more than “video press releases.” Questions about the lack of identification as government-produced media have been sidestepped by shifting blame to the station managers for failing to inform viewers as to what they are watching.

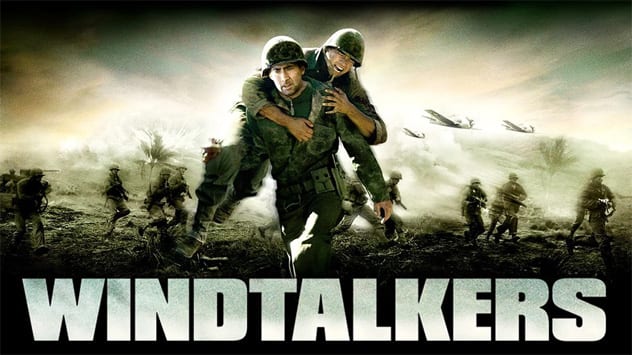

2The Entertainment Liaison Offices

Each branch of the US military has what is known as an Entertainment Liaison Office, tasked with coordinating with the producers of media to project the most favorable image possible of their branches. Obviously, several films are made about the military, and some senior officers review 30–50 feature scripts per year. This is not just for technical accuracy but to help preserve public image. For example, scenes featuring atrocities or questionable actions by US soldiers can be cut (as in the World War II–era period film Windtalkers), or a script’s entire tone can be altered to make the military appear sexy and cool (as in the 1986 film Top Gun). Military branches have also actively endeavored to get their veterans—especially ones with interesting stories—onto reality TV shows for as long as the genre has been popular, according to a 2015 Freedom of Information Act release from the Department of Defense.

1Pentagon Military Analyst Program

During times of military conflict, television news coverage heavily features military analysts—usually retired officers with years of experience—to make sense of the situation for the viewing audience. A 2008 New York Times piece exposed this practice as perhaps the most potentially harmful domestic propaganda campaign ever mounted. The Times uncovered a concerted effort by the Pentagon to get only certain men on the air, men with close business or political ties to over 150 military contractors, whom one may recognize as those least likely to have an impartial opinion on military activity. This was intended as a sort of “media Trojan horse” to shape the coverage of terrorism and military campaigns from the inside—and thus influence public opinion in favor of continued military activity, keeping the defense contracts rolling in. If all of this seems to be in direct violation of the aforementioned Smith-Mundt act prohibiting domestic propaganda, it very well may have been. But the point is probably moot. The 2013 version of the National Defense Authorization Act, which must be renewed yearly, contained an amendment that effectively repealed Smith-Bundt, making propaganda aimed at us, by our government, legal once more.

+ Further Reading

If you want to read more propaganda and you can’t be bothered to switch on CNN, here are some lists from the archives! 10 Shady Origins Of Consumerism In The US 10 Propaganda Campaigns That Backfired Spectacularly 10 Unusual Forms Of Propaganda Actually Used By Governments 10 Disturbing Examples Of Musical Propaganda