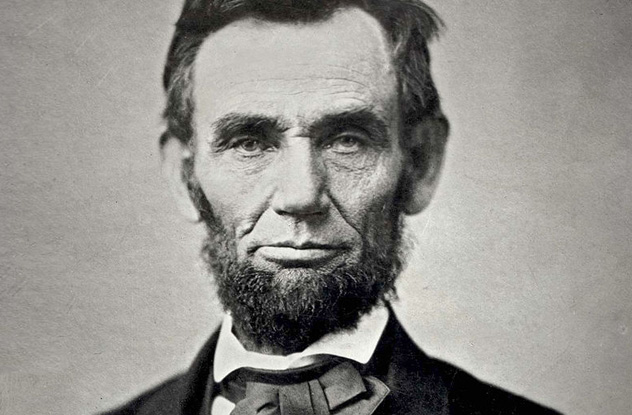

10Lincoln’s Last Breaths May Have Saved Others For Years To Come

Dr. Charles Leale, the doctor who initially treated Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre after he was shot, performed a then-unconventional treatment on the dying president: mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Although it was considered an acceptable treatment in some places in the 1700s, mouth-to-mouth was no longer in fashion in the 1800s. Doctors of the time believed it went against the will of God to bring someone back from the dead. Leale had already tried the typical method used at that time, raising and lowering the patient’s arms (the “Silvester maneuver“). When it didn’t work, he performed mouth-to-mouth. Although Leale didn’t mention it in his short report right after the assassination, he did recount what happened in “Lincoln’s Last Hours,” a more detailed report he read publicly in 1909. “I leaned forcibly forward directly over his body, thorax to thorax, face to face, and several times drew in a long breath, then forcibly expanded his lungs and improved respiration,” said Leale. Although he had saved the president from instant death, Leale knew that Lincoln’s wound was mortal. The president drew his final breath on April 15, 1865, at 7:22 AM. Some believe that Leale’s speech led to the adoption of this lifesaving technique by the medical establishment years later. The medical journal The Lancet was the first to endorse mouth-to-mouth a month after Leale spoke. Other favorable articles were published in the following decades until mouth-to-mouth was formally reestablished as an acceptable method of resuscitation in the late 1950s.

9The Woman’s Life Lincoln Changed On The Day He Died

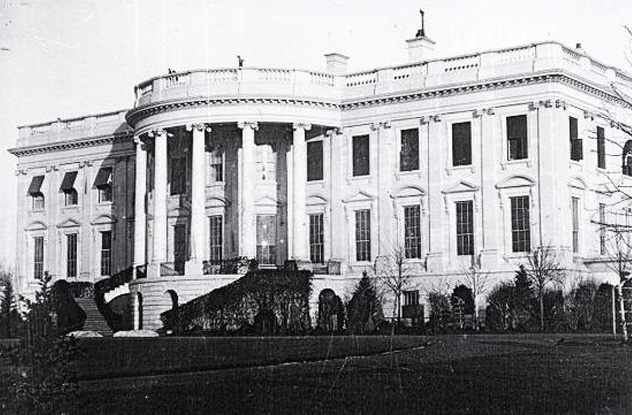

Nancy Bushrod, an emancipated slave, came to see Lincoln at the White House seven hours before he was assassinated. His guards were shooing her out when Lincoln overrode them and invited Ms. Bushrod into his office. She told the president that her husband was fighting in the Union Army, but for some unknown reason, she no longer received his soldier’s pay. She couldn’t find work, and her three young children were hungry. Lincoln said he would take care of it and asked her to return the following day. He also advised her to make sure she sent her children to school. She was astonished that he treated her so well. When she returned the following day, Lincoln had already been assassinated. But a police officer was so moved by her story that he got her a job at Ford’s Theatre, according to a 1930 Christian Herald article. Ms. Bushrod always remembered Lincoln’s advice to send her children to school. She saved every cent she could to make that happen. One grew up to become a minister, and another became a teacher.

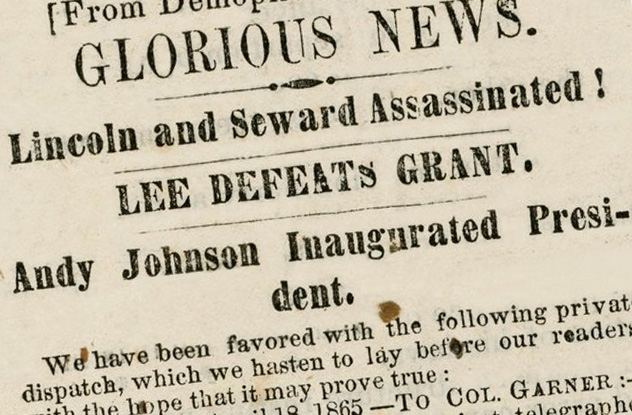

8The Newspapers’ Reaction To The Assassination

It took months for Lincoln to be universally revered in print. Initially, some Southern papers said he was struck down for what he had done in the Civil War and was now going to answer for it in eternity. Publicly, some anti-Lincoln men were openly joyful about his death. In some cases, they died for expressing such beliefs. Booth had written an April 14 letter about the assassination to the Washington newspaper National Intelligencer. He thought the letter would vindicate him for posterity when it was published. But the person Booth entrusted to deliver it never did so. Instead, that person burned the letter to avoid a charge of complicity in the assassination. Although that man, a fellow actor, claimed to remember all 11 paragraphs years later, we’ll never be sure what the letter said. However, Booth’s recovered diary does give us some idea of his delusions about his heinous act. After the assassination, when Booth saw newspapers describe him as a monster who had killed a beloved president, he recorded his thoughts in a pocket diary. “I am here in despair,” he wrote on April 21 or 22. “And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for, what made [William] Tell a hero. And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

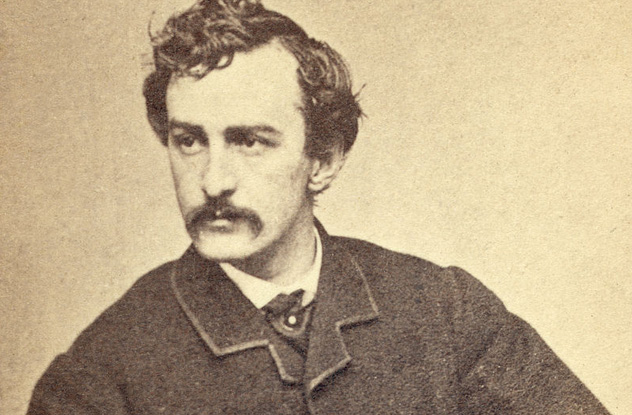

7The Lone Autopsy Photo Of John Wilkes Booth Is Missing

On April 26, 1865, Booth was shot in a barn in Virginia for assassinating Lincoln. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton tried to control the number of photographs taken of Booth after his death so that he wouldn’t become a martyr. The lone photo was taken on April 27, 1865, by Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan during Booth’s autopsy on the USS Montauk. But the picture was never seen again. This led to some interesting conspiracy theories that Booth was still alive. One theory claimed that a co-conspirator was shot instead and was misidentified because he had Booth’s personal papers on him. In 1877, a supposedly dying man revealed that he was Booth. He said that Vice President Andrew Johnson had arranged the assassination and later helped Booth escape. There is still the question of whether the photo will surface again someday. John Wardell, the government detective who delivered the picture to the War Department, claimed he gave the print and the glass plate (the negative) to Colonel L.C. Baker. “The War Department was very determined to make sure that Booth was not made a hero, and some rebel would give a good price for one of those pictures of the plate,” said Wardell, explaining why he thought the photo would never be found. Still, some modern historians believe it may be discovered someday, perhaps lying among the records of the National Archives War Department.

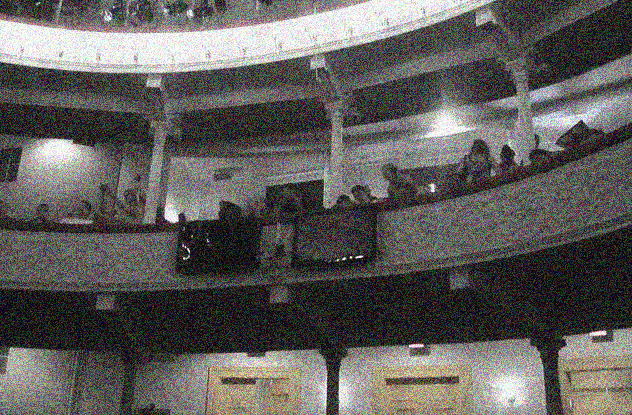

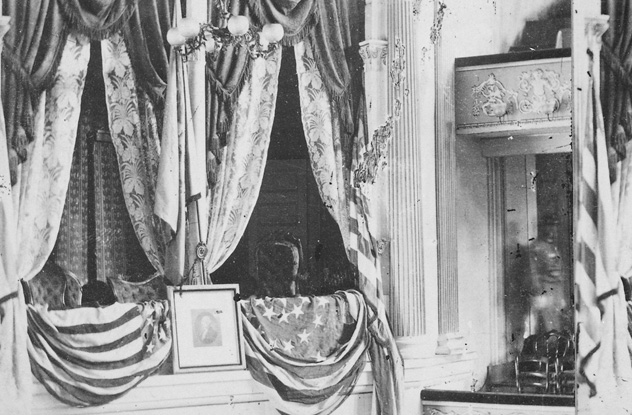

6Ford’s Theatre Was The Scene Of An Even Greater Loss Of Life

There was a lot of controversy when John Ford tried to reopen his theater a few months after Lincoln was assassinated there. After Ford received an anonymous threatening letter, the judge advocate dispatched soldiers to prevent the reopening so that the theater wouldn’t be burned down. Ford never did reopen the venue. Eventually, the government bought the property from Ford. After temporarily using it for the Army Medical Museum, the government converted the building into a War Department pension office in the 1880s. Controversy erupted again over the safety of the structure and the government’s alleged unwillingness to spend adequate money to repair the building. In 1893, Colonel Fred Ainsworth, the highly disliked pension bureau chief who had increased his employees’ workloads, installed an electric plant for the building to provide his employees with electric lights. As an area of the basement was excavated to prepare for the installation, some clerks spotted plaster falling from the ceiling above them. On June 9, 1893, upper floors in the building collapsed, killing over 20 government clerks and injuring 105 more. Emotions ran high as the survivors looked to assess blame. Although the coroner’s inquest found Ainsworth, the contractor, the mechanical engineer, and the building superintendent all guilty of criminal negligence, the finding carried no legal weight unless the district attorney pressed charges. In the end, no one was prosecuted. Each of the victims was financially compensated by the government, with an upper limit of $5,000 for each of those who died.

5Lincoln Once Watched Booth In A Play At Ford’s Theatre

Booth was a well-known, charismatic actor, similar to a Hollywood celebrity in today’s terms. “We think of killers as frustrated losers, loners,” said author Michael Kauffman, a Lincoln assassination scholar. “But Lincoln was shot by a man who was very prominent—a very successful and known man with amazing friends in high places.” Booth was also a ladies’ man before Lincoln died and was once known as “the handsomest man in America.” As Booth began to stalk Lincoln in preparation for the assassination, the actor wrote to John Ford to schedule his appearance in the play The Marble Heart. The production ran at Ford’s Theatre from November 2–15, 1863. Lincoln attended the play on November 9, just days before the Gettysburg Address, watching from the same box where he would be assassinated less than two years later. A big fan of John Booth, Lincoln loved the play and wanted to meet the actor. The president had a note delivered backstage inviting Booth to the White House. But the actor dodged the invitation. Fittingly, Booth starred as the villain of the play. In a public omen of the actor’s real-life murderous intent, Booth directed some of his villainous lines toward the president. “Twice, Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln’s face,” wrote Mary Clay, who accompanied the Lincolns that night. “When he came a third time, I was impressed by it, and said, ‘Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.’ ‘Well,’ [Lincoln] said, ‘he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?’ ”

4Lincoln’s Bodyguard Left His Post On The Night Of The Assassination

Officer John Parker, Lincoln’s bodyguard, was supposed to be at Ford’s Theatre guarding the president on the night of the assassination. But Parker left his post outside the president’s box, first to get a better seat from which to see the play and later to go drinking at the Star Saloon next to the theater. His behavior wasn’t unusual for him. Before his assignment to the president’s detail, Parker had an unreliable record of performing his duties as a police officer. It’s unknown if he ever went back to Ford’s Theatre that night. But in a surprising twist, Booth had also been drinking at the Star Saloon to embolden himself to carry out the murder. Some scholars believe Parker may not have stopped the assassination even if he had been there. Remember: This was an actor the president had always wanted to meet. If Booth had requested to see the president that night, he might have been permitted inside Lincoln’s box without concern for the president’s safety. However, William H. Crook, another presidential bodyguard, wasn’t so forgiving. He directly stated in his memoir that Lincoln would not have died if Parker had guarded Lincoln properly. Parker was never prosecuted on any charges, nor was he publicly vilified in the newspapers or the official report of Lincoln’s assassination. In another strange twist, Parker continued to be a bodyguard at the White House after the assassination, once even assigned to guard Mrs. Lincoln before she moved away. She felt the same as William Crook. “So you are on guard tonight,” Mrs. Lincoln yelled, “on guard in the White House after helping to murder the president.” Some historians believe that Mrs. Lincoln was related to Parker. Only a few weeks before her husband died, she wrote a letter to have Parker exempted from the draft. Three years after the assassination, Parker was finally fired for sleeping on the job.

3I’ve Got A Secret

President Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, so it seems impossible that you could watch any type of living history about it on television. They could barely take good black-and-white photographs in those days. And yet someone alive when Lincoln was president would end up on a television show decades later. Enter Samuel J. Seymour, stage left, on the 1950s TV game show I’ve Got a Secret. On the show, a panel of actors and TV personalities would try to determine a guest’s unusual secret by asking questions that could only be answered “yes” or “no.” If a panelist didn’t guess correctly in a certain amount of time, the next panelist would ask questions. The guest got a small amount of money for each panelist who was stumped. However, when 96-year-old Seymour visited on February 9, 1956, the panel figured out his secret quickly. The show gave him the full amount of money anyway. The poor guy had fallen down the steps at the hotel where he was staying while waiting to record his TV appearance. His health declined rapidly after the fall, possibly contributing to his death just a couple of months later. He did have an amazing secret, though. Seymour was the last surviving witness to the Lincoln assassination in Ford’s Theatre in 1865. He had been five years old at the time. Seymour had traveled with his father on a business trip to Washington, DC. While there, his godmother had taken them to see the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre with Lincoln in attendance. As they sat in the balcony across from the president’s box, Seymour’s godmother lifted him up to get a good look at the president, who was waving and smiling at the audience when he arrived. The boy remembered Lincoln as “[looking] stern because of his whiskers.” Seymour didn’t actually see the shooting. Instead, he heard the shot and someone screaming. Then he saw Lincoln slump in his chair and Booth jump onto the stage and hurt his leg. The five-year-old didn’t understand what was going on. In his innocence, he wanted to help Booth because he had fallen.

2The Doctor’s Notes Of Lincoln’s Last Hours

After Lincoln was shot, his personal physician, Dr. Robert King Stone, took over the case and relieved Dr. Leale of duty. The doctors agreed that Lincoln was going to die of his wounds. After the shooting, Lincoln had been carried, paralyzed and unconscious, to a boarding house across the street from Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln’s tall body was positioned diagonally on a small bed because he wouldn’t fit lengthwise. It was a bed where Booth had also slept in earlier days. Dr. Stone made rather detailed notes of Lincoln’s condition and his treatment during those final hours of the president’s life. The pages are stained with blood. According to the notes, Lincoln’s left eye was blackened by the head wound from the bullet. His right eye was dilated and unmoving. His breathing became labored, so Stone unsuccessfully tried to probe the wound for the bullet in Lincoln’s head. Modern doctors think that may have caused more intracranial pressure. Stone noted that Lincoln’s hair and scalp had not been burned by the bullet. The doctor also applied mustard poultices to Lincoln’s limbs and stomach. But of course, nothing prevented the president’s death.

1The Religious Controversy Over Lincoln’s Last Words

For a man who had mocked religion most of his life, Lincoln’s last words were reportedly of a Savior and taking a pilgrimage with Mary Todd Lincoln. Lincoln and his wife had experienced unremitting sadness for the three years since their son, Willie, had died of typhoid. On the carriage ride to the theater the night of Lincoln’s assassination, their moods were uncharacteristically light, and Lincoln was even flirting a bit with his wife. The lightness continued in the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre. As the play went on, Lincoln and his wife talked of plans for the future. “We will visit the Holy Land and see those places hallowed by the footsteps of the Savior,” Lincoln told his wife. “There is no place I so much desire to see as Jerusalem.” Supposedly, these were the last words he spoke before being shot. This conversation was believed to have been recounted by Mrs. Lincoln to Pastor Noyes W. Miner in 1882. He wrote them down in a manuscript, Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, which is stored at the Illinois State Historical Library. The highly regarded Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln also contains the account. Some Lincoln scholars believe this conversation has been confirmed. But the religious overtones have made teachers and other scholars reluctant to talk about it. And some flat out don’t believe it. On the other hand, Lincoln supported the Jews, which may have had something to do with his words about going to the Holy Land.