We know that knights had a coat of arms which they wore on the battlefield to distinguish themselves when they were covered head to foot in armor. But for most of us, our understanding stops there. For instance, most of us don’t know how a father and son from the same family would be distinguished from each other in battle. Or, say, a noble from his bastard son. But heraldry has existed for hundreds of years. Over time, especially as rank and family became important, it developed into more of a science with rules for both the creation and alteration of arms. Here, we’ve brought together 10 little-known facts about heraldry.

10 The Birth Of Heraldry

For something that came to be such a defining feature of the medieval noble identity, the past of heraldry is surprisingly shrouded in mystery. The knights on the Bayeux Tapestry have marks that look like heraldry, but the marks of individual knights change between scenes. It was a full century before knights started putting “charges” (images) on their shields that were associated with their families. The first English king to use heraldry was Richard the Lionheart, who bore a lion rampant (standing up) on his shield. However, he is also said to have taken the star and crescent as his personal symbol. This tells us that even then, by the end of the 1200s, people weren’t associating a single symbol with their family. The first case of inherited arms is that of Geoffrey Plantagenet and William Longespee. Henry I gave Geoffrey a blue shield decorated with golden lions when Henry knighted Geoffrey in 1127–28. When Geoffrey died, his heir, William Longespee (Longsword), must have taken the symbol as his own because he is depicted on his tomb bearing the same shield in 1226. So he inherited the symbol from his father.[1] Both these men were members of the royal family, and they all used lions in various combinations and styles as their personal symbols. The first use of the modern royal arms of England, the three lions passant (walking), was on Richard the Lionheart’s royal seal in 1198. They have featured in every royal seal since. Over time, the members of the royal family coalesced around the three lions, and they became the symbol of both their family and England.

9 The Roll Of Arms

As the idea of heraldry developed into something more concrete, the need to catalog and record coats of arms grew with it. A roll of arms was a manuscript that blazoned and emblazoned (described and illustrated) the arms of knights, and they became longer and more common as the Middle Ages progressed. The earliest English example known today is Glover’s Roll from the 1250s which features 55 coats of arms. The oldest French roll, The Bigot Roll, dates to 1254 and contains 300 arms.[2] By this time, heraldry was not only developed but fully entrenched in medieval Western Europe. The art of recording it spread rapidly. By 1285 in England, three manuscripts (The Heralds’ Roll, St. George’s Roll, and Charles’s Roll) together recorded over 1,500 coats of arms. While rolls of arms have been kept by the College of Arms in England since the late 1200s, the vast majority of them were produced locally by commissioned scribes or to record participants in tournaments or battles. Nearly every one of these arms follows the rules of heraldic design, particularly the rule of tinctures.

8 The Rule Of Tinctures

In medieval times, the primary purpose of heraldry was to allow people to be easily identified on the battlefield. To ensure heraldry remained clear and easy to see even at a distance, arms were required to follow the rule of tinctures, an archaic word for colors. The primary heraldic tinctures are: red (gules), blue (azure), green (vert), black (sable), purple (purpure), gold (or), and silver (argent). Gold and silver—which are drawn as yellow and white—are known as the “metals,” and the others are known as the “colors.” According to the rule of tinctures, a metal cannot be placed on a metal and a color cannot be placed on a color. For example, a coat of arms couldn’t be a blue lion on a black background or a yellow lion on a white background. The rule of tinctures was observed more strictly in some countries—and by some heralds—than others, and it was considered fine for a metal or color to overlap with another only partly. In fact, the arms of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights of medieval times, comes close to breaking the rule by placing a red lion on a yellow-and-green background.[3]

7 Degradation Of Arms

There are many myths about the ways that coats of arms could be marked as those of traitors, including the use of different colors (usually dark red or orange) or by putting certain marks on them. But these are almost certainly fabrications. The first accounts appear in the 1500s when heraldry was on the decline, and there isn’t a single contemporary example of these being used. However, arms could be disgraced by abatement, the act of displaying them upside down. The town of Castello Rodrigo in Portugal is the only known case of a coat of arms displaying an abatement. The town’s arms show the coat of arms of Portugal reversed. The town refused to open the gates to one of the Portuguese contestants for the throne during the civil war of 1383–85. After the war, they were granted the abated coat of arms as a punishment for their disloyalty. Abatement was most often used on the individual. For example, when Hugh Despenser the Younger was executed for treason in the 1300s, he was made to wear a tabard with his coat of arms turned upside down on the way to his hanging. This became common practice in medieval England.[4]

6 Lozenges For Women

The heraldic tradition is still quite conservative today. Some heraldic traditions continue the practice of single women from noble families bearing their family’s arms on a diamond or “lozenge” shape instead of a shield because the shield was a martial, male image in the eyes of some. While many heraldic traditions have dropped this practice today, the British royal family continues it. When Kate Middleton was issued her personal coat of arms shortly before her marriage to Prince William, it was granted as an elaborate lozenge shape. Other female members of the royal family, like Princess Anne, still display their arms on a lozenge.[5]

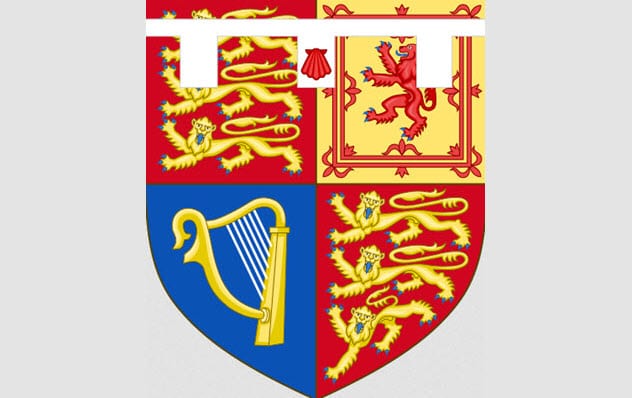

5 Marriage And Impalement

In British heraldry, when a man and woman who both have arms are married, their arms are “impaled” together on the woman’s coat. She can then display her arms on a shield. Impalement is the act of putting both coats of arms on the same symbol. Usually, they are placed side by side, with the man’s arms on the left side of the shield and the woman’s on the right. After Meghan Markle was married, for example, her coat of arms became impaled with Prince Harry’s. However, if the woman is an heiress, her coat of arms is shown on a small shield (called an escutcheon of pretence) in the center of her husband’s arms.[6] In most other heraldic traditions, the arms of a married man and woman are presented side by side, often with the corners of each shield tilted to touch the other. Any charges on the shields (monsters or animals) are turned to face each other.

4 Cadency Marks

The medieval battlefield could be a chaotic and confusing place—even more so if there were several members of the same noble family involved. In these situations or when several members of the same family attended a tournament, it became necessary to distinguish between different members of a family by slightly altering their coats of arms. Traditionally, this was done by adding a “label,” a small band with rectangles hanging from it, to a person’s arms. These marks were known as cadency marks, or difference marks. The British royal family has used the same system of cadency marks for centuries. Only the monarch can display the true arms. The heir apparent displays the arms with a plain white label over them, while successive heirs display a white label with small charges on them with more charges for heirs lower down the succession line. However, the actual charge displayed isn’t fixed. For example, Harry and William have red scallops as their charges on their cadency marks. This symbol is taken from the arms of the house of Spencer, to which their mother belonged.[7]

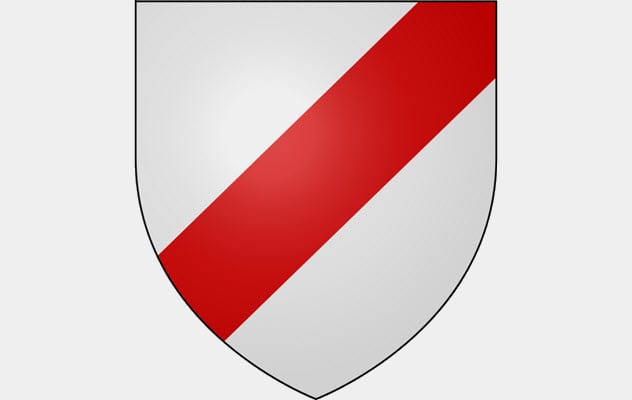

3 Illegitimacy Marks

What about bastard children who were ineligible to succeed the head of a family? They were still the children of a noble family, so they still had the right to bear their arms. But they were not considered eligible heirs to the inheritance, so they had to use different marks than the normal heirs.[8] By far, the most common symbol used to mark a bastard heir was the use of the bend sinister, or a strip that runs diagonally across the shield from the top right to the bottom left. It is important to note that these marks were not considered marks of shame or punishment, just ways of identifying different members of a family both on and off the field of battle. Bastards were also entitled to their own personal coats of arms instead, as long as they were sufficiently different from and couldn’t be mistaken for their family’s arms. Many bastards happily took up this opportunity.

2 Disputing Coats Of Arms

Considering the age and nature of heraldry, it’s no surprise that there is a method for disputing ownership of arms. It’s been frequently used for as many years, though the last case in the modern age was in the 1950s. If two or more people or organizations dispute the ownership of arms, they can fight the case in the High Court of Chivalry, which will determine who has the securest right to the arms by assessing each side’s evidence. (They usually rule in defense of the party with the oldest claim).[9] The High Court of Chivalry has existed since the 1300s. But it is rarely used in recent times, having only one permanent judge—the Duke of Norfolk. The Court has only had to sit once in the last 200 years, in the 1950s, and then had to judge whether it still existed or not before the trial began. But if you live in England and discover that you are the rightful holder of a coat of arms, there is an official body to which to take your claim!

1 Corporate Coats Of Arms

Arms are not exclusively available to families. They are freely available to groups and organizations, too, and have been for centuries. Many of the more prestigious guilds in medieval times were granted coats of arms. A lot of companies today also have them, though they choose not to show them. For example, Tesco in the UK has a coat of arms but rarely, if ever, displays it. In contrast, the Hudson’s Bay Company is much more open to displaying its arms.[10] On the website of the College of Arms, they say that an organization can commission an official coat of arms for around £16,000 on average, though they are occasionally given for free to organizations for charity work or other socially beneficial activities. Incidentally, an individual can apply for a coat of arms, too, for the price of £6,400 (if they determine you have accomplished enough to be worthy of one, of course).