Beginning its adult life as the capital for the Eastern part of the Roman Empire, the city of Constantinople—later Byzantium, and Istanbul today—became the center of an extremely vibrant society that preserved Greek and Roman traditions while much of Western Europe slipped into the Dark Ages. The Byzantine Empire protected Western Europe’s legacy until barbarism waned, when finally the preserved Greek and Roman masterworks opened the eyes of Europeans and stoked the fires of the Renaissance. Many historians have agreed that without Byzantium to protect it, Europe would have been overrun by the tide of Islamic invaders. The purpose of this list is for the readers to take an accurate historical journey—based on real facts—very much worth taking.

The origins of Byzantium are clouded by mystery, but for our list we will follow the generally accepted version. Around 660 B.C., a Greek citizen, Byzas, from the town of Megara near Athens, consulted the oracle of Apollo at Delphi. Byzas requested advice on where he should found a new colony, since the mainland of Greece was becoming overpopulated. The oracle simply whispered, “opposite the blind.” Byzas didn’t understand the message, but he sailed northeast across the Aegean Sea. When he came to the Bosphorus Strait, he realized what the oracle must have meant. Seeing the Greek city of Chalcedon, he thought that its founders must have been blind, because they had not seen the obviously superior site just half a mile away on the other side of the strait. So he founded his settlement on the better site, and called it Byzantium after himself.

Byzantium had an excellent harbor and many good fishing spots in its vicinity. It occupied a strategic position between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, and therefore soon became a leading port and trade center, linking the continents of Europe and Asia. Occupation, destruction and regeneration became the rule for the city. In 590 B.C., Byzantium was destroyed by the Persians. It was later rebuilt by the Spartans, and then fought over by Athens and Sparta until 336 B.C. From 336 to 323 B.C., it was under the control of the famous Greek general, Alexander the Great. After the death of Alexander, Byzantium finally regained its independence. In the following years, right before the city became the capital of one of the greatest empires ever, it was attacked by various invaders such as the Scythians, the Celts, and of course the Romans.

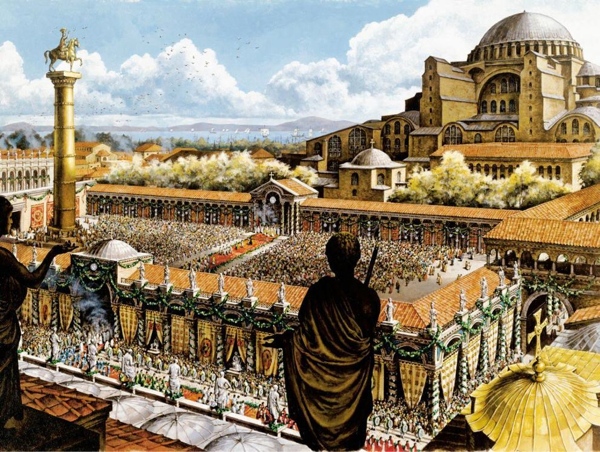

In A.D. 324 the Emperor of the West, Constantine I, defeated the Emperors of the East, Maxentius and Licinius, in the civil wars of the Tetrarchy. Constantine became the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire—though the complete conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity was not accomplished during his lifetime. There’s no doubt that during the rule of Constantine, Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire—but it’s very possible that Constantine’s biggest regret was that he was never able to achieve a unified Christian Church. The construction of the city of Constantinople, however, was one of his absolute triumphs. While other Ancient Greek and Roman emperors built many fine cities during their reign, Constantinople exceeded them all in size and magnificence. It soon became the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and thus marked the dawn of a new era.

Most historians today have trouble deciding exactly which event or date signifies the fall of the Roman Empire. One of the most common conclusions is that when the Empire was split in two, it would never be able to reach its former glory again. There’s even more debate on the religions of the age, which were probably the decisive factor separating the Byzantine Empire from the spirit of Classical Rome. Theodosius I was the last emperor to rule over the whole Roman Empire. He was also the one who split it right down the middle, giving Rome (West) to his son Honorius and Constantinople (East) to his other son Arcadius. The more classical, Western part of the Roman Empire weakened significantly when the land was divided, while the Greek-influenced Eastern half continued to develop the oriental aspects of its culture. The Roman Empire, as the world had known it, no longer existed.

One of the most widely known contributions of Justinian I was the reform of the laws of the Byzantine Empire, known as “The Justinian Code.” Under his rule the Byzantine Empire flourished and prospered in many ways. Justinian gained power and fame for his buildings and architecture. One of his most famous buildings was the Hagia Sophia, which was completed in A.D. 538. It became the center of the Greek Orthodox Church for a number of centuries. This massive cathedral still stands today in Istanbul, and remains one of the largest and most impressive churches in the world. Justinian also encouraged music, arts, and drama. As a masterful builder himself, Justinian commissioned new roads, bridges, aqueducts, baths, and a variety of other public works. Justinian is considered a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church nowadays, even though a good amount of Orthodox Christians don’t agree with his sanctification.

Most historians agree that after the accession to the Byzantine throne of Heraclius in 610 A.D., the Byzantine Empire became essentially Greek in both culture and spirit. Heraclius made Greek the official language of the Empire, and it had already become the most widely spoken language of the Byzantine population. The Byzantine Empire, having had its origins in the Eastern Roman Empire, now evolved into something new—something different from its predecessor. By 650 A.D., only a very few lingering Roman elements remained alongside the pervasive Greek influence. According to various historical sources, a large majority of the Byzantine population from 650 A.D. onwards was of Greek cultural background. Additionally, the Byzantine army fought in a style which was much closer to that of the Ancient Athenians and Spartans than that of the Roman Legions.

The Byzantine Navy was the first to employ a terrifying liquid in naval battles. The liquid was pumped onto enemy ships and troops through large siphons mounted on the Byzantine ships’ prows. It would ignite upon contact with seawater, and could only be extinguished with great difficulty. The ingredients of “Greek fire” were closely guarded, but historians think it was a mixture of naphtha, pitch, sulfur, lithium, potassium, metallic sodium, calcium phosphide and a petroleum base. Other nations eventually came up with similar version of the stuff, but the fact that it was dangerous for their own troops, too, made it go out of military fashion by the mid-to-late fifteenth century.

When we hear the term “Greco-Roman,” we automatically think of culture, architecture, philosophy, the Olympic sport of wrestling—but not of Byzantine cuisine. To learn about Byzantine cuisine properly, we need to go back to its roots. It involved a mix of Greek practices and Roman traditions. Byzantine culinary tastes focused on the regions where Hellenism flourished: cheese, figs, eggs, olive oil, walnuts, almonds, apples, and pears, were all staples of the Byzantine diet, indigenous to the lands of the empire and appreciated by aristocracy and common people alike. The Byzantines also loved honey, and often used it in cooking as a sweetener, since sugar was not available. Bread was an essential staple of the Byzantine table, and a guarantee of stability for the government in Constantinople. And it was a massive enterprise—the bakeries of Constantinople regularly producing over 80,000 loafs per day. The Byzantines could count on a steady diet of bread, cheese, meat, and fish, much of it cured and preserved in salt and olive oil. But just like in modern Greece, this diet was supplemented with vegetables that were produced in small gardens. Despite the limited information we have today, our knowledge of Byzantine cuisine is like the restoration of a damaged mosaic; even though a lot of the pieces are still missing, the picture still has a beautiful quality to it . Today, the aromas and ingredients of Greek and other Mediterranean food gives us a little taste of what Byzantine food must have been like.

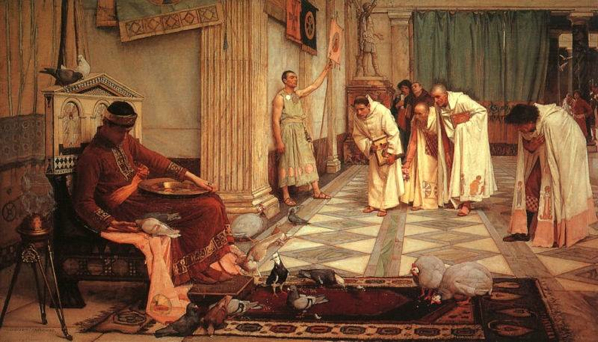

The Byzantine Empire was mainly comprised of an array of small towns and seaports connected by a developed infrastructure. Production was very high, and there was a notable growth in land ownership. The Byzantines followed a Christian lifestyle which revolved around the home, where women dedicated themselves to the upbringing of their children. There were also various public places where men sought relaxation in their leisure hours. From A.D. 500 to A.D. 1200, Byzantium was the wealthiest nation in Europe and western Asia. Its standard of living was unrivaled by other nations in Europe, and it led much of the world in art, science, trade, and architecture. We could even say that the “Byzantine Dream” existed long before the American one.

Most historians of Byzantium agree that the Empire’s greatest and most lasting legacy was the birth of Greek Orthodox Christianity. Eastern Orthodoxy arose as a distinct branch of Christianity after the “Great Schism” of the eleventh century between Eastern and Western Christendom. The separation was not sudden. For centuries, there had been significant religious, cultural, and political differences between the Eastern and Western churches. Many historians assure us today that religion was the main reason why Roman culture lost all its influence on the Byzantine Empire. There were major theological differences between Roman Catholics and Greek Orthodox Christians, on topics such as the use of images, the nature of the Holy Spirit, and the role (and identity) of the Pope. Culturally, the Greek East has always tended to be more philosophical, abstract, and mystical in its thinking, whereas the Latin West tended towards a more pragmatic and legal-minded approach. All these factors finally came to a head in 1054 A.D., when Pope Leo IX excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople, who was the leader of the Greek Orthodox Church. In response, the Patriarch condemned the —and nearly one thousand years later, this division in the Christian church has still not been healed. Theodoros II is a budding author and a law graduate. He loves History, Sci-Fi culture, European politics, and exploring the worlds of hidden knowledge. His ideal trip in an ideal world would be to the lost city of Atlantis. Read More: Yahoo Answers Flickr