10 North Pole 6 Sighting

In the 1950s, the Soviet Union pushed into the Arctic region, supposedly deploying a number of drift stations for scientific research when they were actually used for intelligence and strategic advantage. For Canada, there was also the threat that the US would press into the Arctic for military reasons and question Canada’s sovereignty over the ice shelf. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) had been photomapping the North since at least the 1930s, but these “ice reconnaissance” flights increased dramatically after 1945. Canadian weather and signal intelligence stations were also set up in the far north to watch for Russian incursions and to keep the Americans from getting a foot in the door out of “national security” concerns. Between 1953 and 1962, this became particularly important when the Soviet Union performed over 50 atmospheric tests in the Arctic, with fallout often reaching Canadian territory. US intelligence became increasingly dependent on RCAF-provided information for analysis. One of the most dramatic ice reconnaissance flights occurred in May 1958 when an RCAF Lancaster plane flew over a Soviet ice station called “North Pole 6” and discovered a Tupolev Tu-16 Badger nuclear bomber sitting on an ice runway. This was a major coup because no Western country had ever seen or photographed one of these Soviet bombers. The data from the Lancaster allowed Western analysts to make extrapolations about the capabilities of the Soviet bomber. It also revealed that the USSR was thinking of using Arctic way stations to allow bombers to refuel and thereby successfully reach North American targets in a nuclear war.

9 RK-60

In the mid-1950s, the Finnish military was reviewing designs for a new service rifle and considered the AK-47 and M1943 cartridge as the most interesting foreign designs. Their experience fighting in thickly wooded areas at close range meant that they had no bias against lighter-powered automatic rifles. Due to the political situation, however, there was little chance of a direct sale from the Soviets, and no defectors had brought this weapon across the border yet. But the gun was being introduced to Poland, so the Finnish defense forces found a businessman with connections there who was able to arrange the sale of a prototype. Erkki Maristo of the Finnish military’s ordnance department sailed to Poland as a private citizen and purchased a prototype for an undisclosed sum. It was disassembled, and the parts were placed on a commercial vessel sailing from Gdansk to Kotka in Finland. After testing proved acceptable for Finnish needs, the military used a front company called “Ankertex OY” to obtain 100 more of the rifles. They were reverse engineered and became the RK-60, a reliable copy of the Kalashnikov that became the standard Finnish rifle.

8 Karl-Paul Gebauer

The East Germans had a number of spies stealing secrets from the West German military and industry, and one of the most significant was Karl-Paul Gebauer. An employee of IBM Special Systems, he offered his services to the East Germans while employed at the West German navy’s Research and Testing Facility No. 71 near Kiel. He had been cleared by counterintelligence despite a criminal history that included a prison term linked to the death of an American GI shortly after the end of World War II. Gebauer was a security representative handling classified material, which he gave to the East Germans. He provided key intelligence on Projekt Tenne, an IBM communications command system for NATO. In wartime, the information would have allowed the communists to jam the NATO communications system, preventing the transmission of orders from commanders and forcing individual captains to make their own decisions. Gebauer also furnished information about a coding device called “Ecrovax,” classified as “crypto top secret.” In 1976, he delivered six rolls of film containing 13,000 secret documents to the East Germans. Before 1980, when IBM Special Systems shut down, he also handed the East Germans 40 secret files that he was supposed to have destroyed. Gebauer was deactivated in 1986 and paid 70,000 deutsche mark (US$43,700) for his services. But he was eventually fingered by a defector and thrown into prison in Berlin in 1990.

7 The Petrov Affair

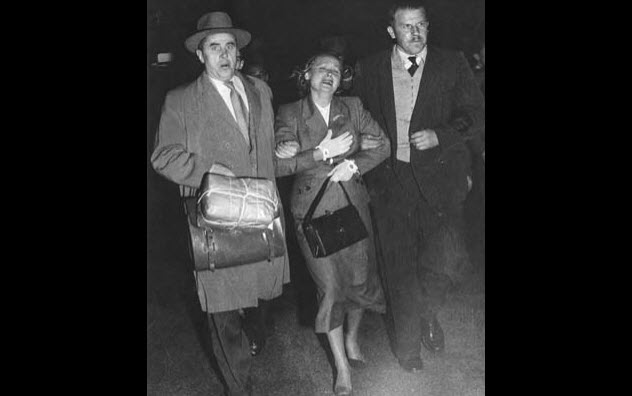

Soviet spy Vladimir Petrov arrived in Australia in 1951 with a mission to establish an Australian spy network, perform surveillance on Soviet citizens, and undermine anti-Soviet movements. He made little progress and was harshly criticized by the Kremlin. Petrov confided his woes to Polish emigre Michael Bialoguski, who worked for the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO) and told Australian intelligence that Petrov was a potential defector. Petrov was given the code name “Cabin Candidate.” In April 1954, after six weeks of negotiations with ASIO, Petrov secured Soviet documents on Soviet intelligence activities in Australia and promptly defected, with ASIO placing him in a safe house in northern Sydney. Soviet authorities initially accused Australia of kidnapping Petrov before they realized the truth. His wife Evdokia was placed under house arrest by the Soviet embassy, and two couriers arrived to take her back to the Soviet Union for trial. At the airport, an angry crowd gathered to prevent her from being put on the plane, but she was pulled aboard with the help of the flight crew. ASIO decided to intervene, and when the plane landed for refueling in Darwin, Evdokia was separated from the couriers and asked if she wanted to stay in Australia. Despite fears for her family in Moscow, she reluctantly agreed. The Petrov documents contained key information about the groups and media outlets that the Soviets had hoped to infiltrate and co-opt. The documents also implicated some staff members of H.V. Evatt, Leader of the Opposition, who accused the Australian government of purchasing forgeries. The Royal Commission ruled that the documents were genuine. Evatt caused hilarity in Parliament when he revealed that he had written a letter to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov asking if the documents were genuine and that Molotov had replied, “No.” With Evatt’s reputation ruined, the Labor Party was thrown into disarray.

6 Radioactive Hair Samples

India’s main foreign intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), was formed after severe intelligence failures in the 1960s during wars with the Pakistanis and the Chinese. Indira Gandhi had pushed for the country to develop an intelligence agency along the lines of the American CIA and had placed it into the capable hands of spymaster Rameshwar Nath Kao. In 1977, RAW received troubling indications that Pakistan was embarking on a nuclear program, but they needed to find out for sure. An agent was dispatched to Kahuta, where it was believed the Pakistani nuclear program was based. He cleverly sent a contact to a hair salon located near the facility. The contact collected hair samples from Kahuta scientists, which were sent to India for analysis. The hair contained high levels of radiation and weapons-grade uranium. Next, the agent found a mole within the facility who was willing to sell a blueprint of the Pakistani nuclear project for cash. However, the newly elected Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai, who supposedly hated RAW, inadvertently turned RAW’s intelligence coup into a win for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). RAW needed the prime minister’s permission to pay the mole with a foreign currency, but Desai refused. Worse yet, in a telephone conversation with Pakistan’s military leader Zia-ul-Haq, Desai said that he knew about the Pakistani nuclear facility at Kahuta. The ISI forcefully went after RAW’s intelligence assets in Pakistan, wiping out their networks and leaving India in the dark about future nuclear developments.

5 Farewell

French intelligence operations are not well-known in the English-speaking world. In 1981, a French businessman delivered a message from “a Soviet friend” to the counterintelligence agency Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST). The friend turned out to be Vladimir I. Vetrov, a senior KGB officer in the First Chief Directorate’s Directorate T, responsible for scientific and technical espionage. Vetrov wanted to switch teams. The DST accepted his offer and gave him the code name “Farewell.” Farewell gave the DST over 4,000 KGB documents on Soviet scientific and technical espionage as well as information on the goals, achievements, and objectives of their program. This information was compiled into the “Farewell Dossier” and sent to the CIA, where the intelligence community was shocked by how many technical samples the KGB had stolen from the West for use by Soviet military and civilian industries. The documents identified 250 KGB “Line X operatives” stationed at Soviet embassies to steal scientific and technical secrets from the West. There was also information on agents who had been recruited by Line X in the US, West Germany, and France. The information helped to decimate the KGB’s network of technology thieves in the West, but Farewell was not long for this world. Vetrov was in a car in a Moscow park with his mistress when a man knocked on the window. Thinking his cover was blown, Vetrov stabbed the man to death, tried to kill his mistress, and fled. When he returned an hour later to get his car, he found the police waiting. Eventually, he was sentenced to 12 years behind bars for murder. As the investigation continued, the KGB noticed strange references to an abandoned “big project” in Vetrov’s mail. Vetrov was interrogated, quickly confessed to the espionage, and was executed in 1983.

4 Operation Meghdoot

High in the Himalayas, the Siachen Glacier has long been a disputed area of sovereignty between India and Pakistan. In 1974, Pakistan began to allow civilian mountaineers from Austria, Japan, the US, and elsewhere to stage expeditions through Pakistan’s Gilgit region, often with members of the Pakistani military tagging along. After the Indian military conducted a fact-finding mission, they began to smell a rat. India believed that Siachen was on their side of the Line of Control in Kashmir and that Pakistan was planning to engage in “mountain poaching.” In August 1983, India’s northern command received two protest notes from Pakistan asking India to cease sending military assets to the Siachen Glacier. Pakistan also appeared to be unilaterally extending the Line of Control. This could have been written off as posturing if RAW hadn’t soon realized that Pakistan was buying Arctic weather gear and equipment in bulk from European sources. In an interview with NDTV, Vikram Sood, RAW chief at that time, explained: “We knew Pakistanis were sending more and more civilian expeditions into Siachen, but its importance was not so apparent until we put two and two together and realized Pakistan was up to something far more serious than just sending mountaineering expeditions into the area. When we got reports of the large-scale snow clothing and high-altitude equipment purchase by Pakistan, there was enough urgency for me to go and share it with [the military]. The Pakistanis were not buying all that for a picnic.” Thanks to RAW, the Indian military launched a quick response with “Operation Meghdoot.” In April 1984, Indian helicopters dropped their troops on Soltoro Range in the Siachen Glacier region before Islamabad could make a move. Pakistani troops tried to dislodge them but were unprepared and unsuccessful. This became known as the “war on the roof of the world” because most of the fighting occurred at elevations above 4,500 meters (15,000 ft).

3 Cracking The Geheimschreiber

In the 1930s, the German company Siemens developed a mechanical teleprinter cipher machine called the “Geheimschreiber.” It combined a form of encryption called “overlaying” with a permutation of the pulse order, making messages harder to decrypt for anyone who didn’t know what permutations were used. This type of encryption would later be used in the famous Enigma code machine. For the Geheimschreiber, there were eight basic patterns with over two billion variations and up to 800 quadrillion settings, making it an exceptionally secure cipher. After the fall of Denmark and Norway in April 1940, the Germans demanded the use of Swedish telephone cables running from Scandinavia to Germany. Soon, the Swedish were intercepting encrypted German messages. The Nazis became overconfident that their cipher could not be cracked, occasionally sending variants of the same message without changing the code. This weakness would soon be exploited by the mathematical genius Arne Beurling. As head of the team tasked with cracking the Geheimschreiber’s code, Beurling was given a wealth of data, including messages sent with the same code. Two weeks later, he had cracked it without previous teleprinter experience or access to a German machine. Through his achievement, Swedish intelligence was suddenly privy to German strategic war plans at the highest security levels, including plans for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II. No one knows how Beurling accomplished this feat, and he refused to say. When pressed to explain himself during a 1976 interview, he testily responded, “A magician does not reveal his secrets.”

2 Peenemunde

Located on Usedom Island in the Baltic Sea, Peenemunde was a center of munitions manufacturing and secret rocket research designed to produce “wonder weapons” for the Nazis, including the V-1 and V-2 rockets that Hitler intended to use to bomb the British and win the war. In August 1943, 586 British bombers dropped over 2,000 tons of explosives on the Nazi facilities, delaying research into the V-2 rockets by up to two months (although testing continued elsewhere). This bombing would not have been possible without information received from the intelligence wing of the Polish Home Army. The first indications of strange Nazi research came from a Polish agent, probably working at the Czech steelworks plant in Witowice. It appeared that the Nazis were doing top secret work on an advanced shell made of hollowed steel ingots. Later, “Source Z,” a Polish agent working at Peenemunde, furnished the Allies with detailed descriptions of the rockets being tested, the slave labor used to produce components, and the precise geographical details of the facilities on Usedom Island. In December 1943, Polish intelligence informed the Allies that new underground research facilities and factories had been built in the Brunn, Wischau, and Olmutz regions in Bavaria. Then in early 1944, a V-2 crashed in the River Bug near a testing ground at Sarnacki and was quickly found by the Polish underground, who camouflaged it with foliage to avoid detection by the Nazis. After the Germans gave up looking, Polish scientists disassembled the rocket. The parts were placed in barrels and stored in a barn in the town of Holowczyce. This allowed the Allies to pull off Operation Most III and take the rocket parts back to Britain.

1 Room 14

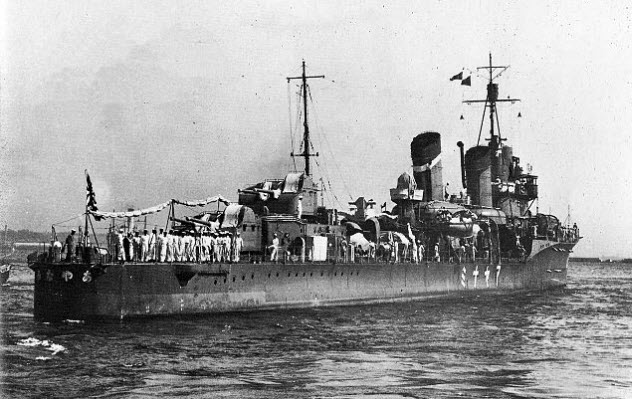

When Japanese politicians began to speak about territorial expansion as a solution to the country’s economic problems, the Dutch became increasingly concerned about the potential threat to the oil-rich Dutch East Indies. The Service of East-Asian Affairs realized that their knowledge of Japanese intentions and capabilities was too limited and they needed better intelligence on the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) shipbuilding, tactical doctrines, and training regimens. A radio monitor station was set up in Batavia to listen to naval communications of the UK, US, France, and Japan, although Japan was the focus of their attention. Netherlands Navy officers began studying both the Japanese language and the art of cryptography. In 1934, Lieutenant-Commander J.F.W. Nuboer became head of a new intelligence section of the Royal Netherlands Navy in Batavia. He was able to use “one-human-brain-processors” to crack Japanese naval codes and produce an accurate naval order of battle for the IJN as well as track individual ship movements by intercepting weather reports indicating the vessels’ names and positions. Much of the work was performed at the cryptographic center in Bandoeng in “Room 14.” It was here that Nuboer and his team cracked ‘.’ (their name for the Japanese code because that was the symbol at the end of each encoded row in a message). ‘.’ was the basic encryption for the IJN, later known by the Americans as the “Blue Code.” But the Dutch cracked it first after intercepting an encrypted telegram from a Japanese training squadron leaving Singapore in 1935. The Dutch were also able to determine that ship codes were ordered by their date of commission and that the list of the geographical names was ordered by comparing their actual locations to Tokyo. A further breakthrough was made when a ship near Formosa sent out two nearly identical encrypted messages. The work helped the Dutch accurately predict Japanese intentions and movements until Nuboer was replaced by another officer and the Japanese shifted to wartime codes that were more secure. After 1937, most intelligence on Japanese naval movements came from submarine or aerial observation.