10 Ibis

Ibis was a popular humpback whale that would often visit the Maine and Cape Cod areas of North America in the late 1970s and 1980s. Humpback whales in the North Atlantic typically migrate between the Bahamas and anywhere from Newfoundland to Greenland or even as far as Norway. Scientists were able to identify Ibis by her individual flukes, which have markings that are equivalent to fingerprints in humans. Migratory routes are recorded by sightings of whales based on this principle. Ibis was a favorite of whale enthusiasts, and scientists had been tracking her since 1979. Then, in 1984, near-tragedy struck. In early October, Ibis was spotted entangled in a huge fishing net used to catch cod and haddock. For nearly two months, Ibis struggled with the fishing net, slowly losing strength. At one point, it was feared that she had drowned, since she seemed to be struggling to reach the surface of the ocean as time progressed. Finally, around Thanksgiving, Ibis was spotted with another humpback that appeared to be trying to assist her. Rescuers were finally able to get close to Ibis, tying floats to the tangled netting to keep her from diving so they could finally cut the netting off. The freeing of Ibis marked the first recorded rescue of a free-swimming whale, and the volunteer group that accomplished the feat would go on to become the Marine Animal Entanglement Response (MAER) team, which has since saved over 200 whales and other cetaceans in similar manners.

9 Delta And Dawn

On May 13, 2007, in the Sacramento River in California, a pair of humpback whales were sighted, appearing to be lost. (Dawn is pictured above.) The whales also had wounds that appeared to be from boat propellers. Spectators and volunteers followed the whales up and down the river, coaxing them back in the direction of the San Francisco Bay area. Rescue teams from the California Department of Fish & Game tried everything from whale songs to bagpipes to get the pair of whales to stop swimming upstream. The rescue became a national and worldwide effort, as well, when scientists treated the humpbacks’ wounds with antibiotics, which were donated by Pfizer & Bayer. The drugs were injected with a 0.6-meter-long (2 ft) syringe from New Zealand. An expert from the Hawaii Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary suggested using fire hoses to pressure the whales back downstream. After 18 days, with their skin conditions deteriorating because of prolonged exposure to fresh water, the pair finally reversed course. In an ironic twist, after so much publicity and media coverage, Delta and Dawn rudely disappeared from the San Francisco Bay into the Pacific Ocean on the foggy morning of May 29, 2007, without any confirmed sightings, “thank yous,” or “goodbyes.”

8 Migaloo

In 1991, a pure white humpback whale was spotted near the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, migrating from Antarctica to the coast of northern Australia. After almost 25 years, the white whale called Migaloo is one of Australia’s biggest whale-watching attractions. While there have been other confirmed white humpback sightings, what separates Migaloo from the others is that he is completely white. Other white whales have had black spots or other dark markings that offset their pale color, but Migloo has none of these patterns. Interestingly, scientists do not believe Migaloo to be an albino, since albinos in mammals and most other species have red eyes. Migaloo has the normal, brown eyes of the average humpback. It also seems that there might be another Migaloo roaming the coastal waters of Australia. A white, baby humpback was spotted near the Great Barrier Reef in 2011, although no one has been able to get Migloo to agree to a paternity test to determine if this white offspring is his.

7 Old Tom

According to Australian legend, a 10,000-year pact was made between killer whales and Aborigines called the Law of the Tongue. In what is today known as Twofold Bay on the coast of Eden, killer whales would herd whale pods to Aboriginal whalers. From 1840, European settlers took over, harpooning the whales and leaving the carcasses for the killer whales to eat the tongues, after which the killer whales would leave the remaining carcass for the whalers. Old Tom was the most famous of these killer whales. Old Tom and other orcas would notify whalers at a particular location near the mouth of the Kiah River, thrash their tales, breach, and otherwise make a lot of noise to notify whalers of nearby or approaching pods. Old Tom had a personality of his own, sometimes hanging on to dead carcasses with his pectoral fins to be pulled along by whalers. Sometimes, Old Tom would do the dragging. Unfortunately, as humans often do, in the early 1900s, whalers (presumably not the native whalers) became greedy and began breaking the Law of the Tongue, dragging dead whales away without allowing the orcas to take the tongues as payment. In one instance, Old Tom struggled with a whaler in a game of tug-of-war with a carcass, which Old Tom lost, losing some of his front teeth in the confrontation. This may have lead to Tom’s death, because later, he may not have been able to tear flesh from dead whale carcasses. When Old Tom was found floating in a local cove, he was measured at 7 meters (22 ft) long, a short length for a killer whale. Old Tom was estimated to be at least 70 years old, possibly 80–90 years, when he died.

6 Luna

Luna was a killer whale born to a group called the Southern Resident killer whale community, which lives along the Pacific Northwest of Canada and the United States. When Luna was born, he and his mother were isolated from their pod. This was an oddity, because killer whales are typically protective of mothers and newborn calves. Luna ended up separating from his mother and pod, one of only two documented incidents of an orca calf separating from its family unit and surviving at such a young age. It was speculated he might have been shunned by his mother and later by his pod, although no one knows why. Luna became something of a cautionary tale, similar to the standard rule in national parks that warn against feeding bears. He was popular with tourists, performing tricks, leaping in the air, and then getting close enough to boats for people to stroke his tongue. Unfortunately, Luna could never distinguish between tourist boats and other fishing or industrial vessels. The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans had planned to capture Luna and reintroduce him to his pod, but local native Canadians prevented this, believing Luna to be the spirit of a recently deceased tribal chief. This turned out to be worse for Luna; he finally got too close to the wrong boat and was killed by a propeller.

5 Springer

Springer is the other documented occurrence of an orca calf found isolated from its pod. In 2002, Springer was found off the coast of Vashon Island in Puget Sound. He was suffering from worms and a skin condition, and scientists believed that Springer’s mother might have died not long before she was found. Watch this video on YouTube Fortunately, this story has a much happier ending than Luna’s. After several months of observation, Springer was lifted by crane and delivered to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Manchester Research Station, where a medical team comprised of veterinarians and ocean animal experts spent a month nursing her back to health. Springer was then successfully reintroduced to her pod in July 2002. She was tentative at first, but after a few weeks, she was completely accepted by her pod. Scientists were able to determine her original family by distinctive skin patterns and vocal dialects of communication. Even more gratifying, 11 years later, Springer had mated and given birth to her own calf, making her return to the wild a complete success, proving that once in a while, we humans do get it right.

4 Sassafras The Deaf Dolphin

Sassafras was discovered along the Louisiana Coast in 2012, sunburned, in mere centimeters of muddy seawater. In nursing him back to health, it was discovered that in addition to being a small dolphin at 2 meters (6.5 ft), Sassafras was also deaf. It was speculated that his mother left him to fend for himself at the age of two and half, which is the typical weaning stage for most dolphins. Because of his impairment, Sassafras probably got lost immediately and could not fend for himself. Sassafras was one of almost 800 Gulf Coast mammals to be stranded along the coast beginning in 2010. He was originally intended to be rehabilitated and released back into the wild, until they learned about his lack of sonar. Sassafras was born around the same time as the BP oil spill in 2010, and specialists wondered if the spill played a role in making him deaf. Sassafras was eventually relocated to the Institute for Marine Mammal Studies in Mississippi, where his personality as a show-off became apparent. His story brought attention to the broader issue of mass dolphin die-offs in the Gulf of Mexico that began that same year. While most would like to point to the oil spill as the major contributor, there were other factors, including cold weather and larger-than-normal cold water runoff from melting snow. The oil spill was still a factor, though.

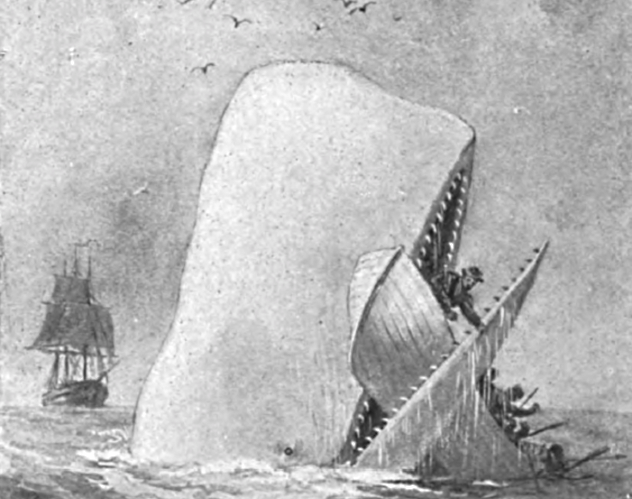

3 Mocha Dick

The average high-school or college English student has likely heard of the Herman Melville novel, Moby Dick. What those students probably don’t realize is that Melville was inspired by real events. In 1820, the whaling ship Essex, captained by George Pollard, was attacked and sunk by a gigantic sperm whale. The whale, which survivors claimed was around 26 meters (85 ft) in length, rammed the Essex twice, causing the crew of 20 to abandon ship in three lifeboats. Pollard wanted to head toward the closest land—the Marquesas or the Society Islands—but his crew convinced him to try for South America instead, since they had heard the islanders were cannibals. That turned out to be a cruelly ironic decision, since the starving crew soon turned to cannibalism themselves. They even shot Pollard’s cousin outright after drawing lots to see who would be eaten next. Ultimately, only eight members of the crew would survive. An even more direct inspiration was a white sperm whale known as Mocha Dick that became infamous for smashing whaling boats and killing sailors in the waters off Chile, sometimes in defense of dead or dying whales. The white whale was known for his cunning, once even seeming to play dead in order to lure boats close to him, before roaring to life and attacking. When one whaler swore to kill him, Mocha Dick smashed three of his boats and forced him to retreat. His rampage continued until he was finally killed in 1859, with 19 harpoons sticking out of him. By that point, Mocha Dick had killed at least 30 men over the course of 100 battles.

2 Pinky

Pinky, however, is not a member of any of these endangered species. Pinky is a saltwater bottlenose dolphin that was discovered in Lake Calcasieu, a saltwater lake estuary in Louisiana, in 2009. Because of genetic albinism, Pinky lacks pigment in his skin and eyes, making him appear pink. Other than spending a little more time underwater than most dolphins, Pinky’s rare condition does not seem to affect his quality of life. While not the first albino dolphin documented in the wild, what is peculiar is that two other known albino dolphins were spotted in and around the Gulf Coast. One was spotted in Little Lake, close to New Orleans, and the other was seen off the coast of Galveston, Texas, making one wonder, who is Pinky’s daddy (or mother)?

1 Mini-Moby

To the average beachgoer, there is no difference between a dolphin and a porpoise, other than the fact that one is easier to pronounce than the other. However, the average marine biologist knows that the porpoise has a short nose and spade-shaped teeth, in addition to being a bit thicker around the middle and not as long. Dolphins are bigger and known for having longer noses and cone-shaped teeth. Mini-Moby is a porpoise, one of only two known Pacific harbor porpoises that is completely white. As we’ve seen, a white whale, dolphin, or porpoise is not all that uncommon. What makes Mini-Moby interesting is his family history. Pacific harbor porpoises disappeared from the San Francisco Bay area for over 65 years. People who grew up near the Bay before the 1930s might have seen and heard the snorting noises of harbor porpoises playing and hunting. Then, in the early 1940s, the US Navy extended a steel net across the mouth of the San Francisco Bay to prevent Axis submarines from entering. Unfortunately, that also prevented the Pacific harbor porpoises from entering as well. When World War II ended, the steel net was removed, but the Bay had become so toxic with collected waste, and commercial fishing had done so much damage, that the porpoises did not return. But, years of conservation efforts have begun to pay off. In 2008, harbor porpoises were again seen in large numbers in the Bay area, and it has become (or perhaps returned to being) a natural breeding ground for these smaller, shorter cousins of the dolphin. Peter is an amateur writer, Internet investigator, and humorist by night who pretends to be a husband, father, and salesman during daylight hours.