10The Last Stand Of The Pharaoh

Around 3,600 years ago, a pharaoh handled his horse skillfully as he led his soldiers on an expedition far from home. He had spent most of his life on horseback, permanently altering the muscles of his femur and pelvis. This was a break with tradition—horses had only recently been introduced to Egypt and were still uncommon in warfare along the Nile. But Pharaoh Senebkay needed every advantage he could get. The mighty empire of Ancient Egypt had broken apart as the invading Hyksos took over the northern part of the country, leaving Senebkay, the self-declared ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt, confined to a rump state around Abydos. Threatened by the Hyksos, Egyptian rivals in Thebes, and at least one major Nubian invasion, the pharaoh had spent most of his life at war. Watch this video on YouTube Around 1600 BC, Senebkay was riding out against his enemies when he found himself under attack. He must have fought back. Tissue recovered from a related mummy revealed a muscular man who built strength by performing repetitive arm motions, probably in the form of combat drills, demonstrating that the Abydos pharaohs were trained to be warriors. The position of Senebkay’s wounds indicate that he fought on horseback, giving him a substantial advantage as he slashed down at his enemies. However, he was surrounded by multiple assailants who stabbed him repeatedly in the knees, hands, and lower back. A powerful cut almost severed his foot entirely. Then he was pulled down. An enemy soldier stepped forward, hefting one of the curved battle-axes common in Egypt at the time. He delivered three massive blows to the pharaoh’s head. Senebkay’s body wasn’t mummified for several weeks, indicating that he died a long way from Abydos. His people may also have had trouble recovering his body. He was laid to rest in a painfully modest tomb, revealing the poverty of his dynasty. Even his sarcophagus had to be stolen from the tomb of an earlier ruler. In fact, Senebkay’s dynasty was so obscure that historians only learned of its existence in 2014, when his tomb was unearthed. The University of Pennsylvania’s Josef Wegner led the study of the pharaoh’s skeleton, revealing the dramatic details of his death.

9A Druid’s Deadly Game

In 1984, a worker cutting peat near Manchester Airport tried to pick up a lump of soil and realized he was holding a human foot. He had discovered Lindow Man, one of the most perfectly preserved “bog bodies” in British history. Thanks to extensive study, we now know a great deal about Lindow Man, including the dramatic details of his last day. Lindow Man died around 2,000 years ago, deep in Celtic Britain. He was young (30 or younger) and handsome. His hands were perfectly manicured, and he was well-nourished, suggesting that he was a man of wealth or power. He had no old scars or injuries, so he probably wasn’t a fighter. Unlike Celtic warriors, who sported only mustaches, Lindow Man had a full beard of red hair. Historians think he was a druid, a priest of the ancient Celts. On the day he died, Lindow Man and his fellow druids played a game. A thin, flat barley cake was cooked over a griddle, with one end allowed to burn until it was black. The druids then broke the cake into pieces and hid them inside a leather bag. They passed the bag around, each taking a piece and eating it. Lindow Man drew the burned one. It was still in his stomach 30 minutes later, when they sacrificed him. The use of a “burned bannock” to choose a sacrificial victim is referenced in Celtic lore, but Lindow Man’s stomach contents were the first solid evidence for its historical use. Was Lindow Man dismayed when he drew the burned piece? If so, he didn’t show it. Analysis of his facial muscles indicate that he went to his death with an expression of calm serenity, outwardly willing to die for the gods. He was naked except for a strip of fox fur around his left arm. To propitiate three gods at once, his fellow druids subjected him to the so-called “Triple Sacrifice.” For Tarainis, they smashed his skull in. For Esus, they strangled him with a cord and cut open his windpipe. And for Teuttates, they drowned him in the bog, where his body would be preserved for the next two millennia.

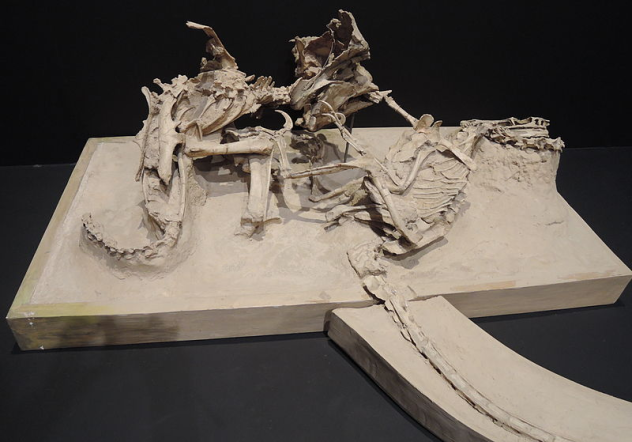

8A Dinosaur Death Match

As it darted across the sand dunes, the velociraptor was hungry. The deserts of Mongolia were a harsh environment during the Upper (Late) Cretaceous, with small herds of dinosaurs eking out an existence around gradually evaporating ponds refreshed by seasonal flooding. Seasonal clouds still hung in the air as the velociraptor navigated the now treacherously sodden landscape. It was small and birdlike, not much bigger than a turkey, with a vicious, curved claw on the second toe of each foot. Its feathers moved in the breeze. The velociraptor was heading into the territory of a protoceratops, a medium-sized herbivore with a ridged head, like a small triceratops without the horns. From other fossils, we know that protoceratops was a good source of food for Mongolian velociraptors. The small carnivores stole eggs, scavenged protoceratops corpses, and probably hunted them as well. Perhaps our velociraptor attacked the protoceratops, or perhaps the territorial protoceratops charged the raptor as it scavenged for eggs. Either way, they fought. It was a brutal battle. The protoceratops threw the raptor to the ground and caught the predator’s right arm in its jaws, biting down hard enough to break it. Shrieking in pain, the raptor desperately seized the herbivore’s head with its left arm. Bringing up its deadly toe-claw, it slashed into the protoceratops’s neck, probably severing an important blood vessel. There are competing theories as to what happened next. Most likely, a nearby sand dune, soaked through by the torrential rain, collapsed and buried the combatants as they struggled together. Such dune collapses were common after rains in the area, helping to make Mongolia one of the richest sites for fossil-hunting. Another theory suggests that the raptor was unable to free itself from beneath the dead protoceratops and starved to death, with the pair being covered by a later dune collapse or sandstorm. Either way, the fossils of the two ancient enemies were uncovered in 1971, frozen in combat for 80 million years.

7The Earliest Known Viking Raid

In June 793, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that “the ravages of heathen men miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne.” The Vikings had arrived in written history. With almost no written sources about the region, the history of Scandinavia before the Lindisfarne raid remains shrouded in mystery. A possible breakthrough came in 2008, when two Scandinavian ships were found at Salme, on the Estonian island of Osel, each filled with dead bodies. Archaeologists believe that the ships belonged to a group of “proto-Vikings,” buried in Estonia after a fierce fight at some point between AD 700 and 750. Thanks to years of careful analysis, we can now go some way toward reconstructing their doomed voyage. The group buried at Salme were warriors, large for their time and bearing the scars of past battles. They were led by a small group of nobles bearing beautiful, decorated swords. The most elaborate sword was found next to a skeleton with an ivory game piece in its mouth. Perhaps the piece was a king. Perhaps the skeleton was, too. They brought at least two Scandinavian ships, probably from an area in modern Sweden. One was old, built some time before 700, and heavily patched. It lacked sails but could be rowed between islands. The seven bodies in the ship had few goods or decorations buried with them, suggesting a lower class. The second ship was newer and more technologically advanced, large enough to hold 33 bodies. It probably had sails. Similar ships would later allow the Vikings to spread terror across Europe. It’s likely that the Salme group came to Estonia on a raid or to collect tribute, but things didn’t go according to plan. Perhaps they were ambushed by rival Vikings; perhaps the Estonians fought back. There was a terrible slaughter. One man had his arm cut in half as he tried to ward off a massive blow. Another warrior had the top of his head chopped off. Arrowheads were inside the skeletons and even where the wood of the ships had rotted away, suggesting that the boats themselves had been attacked. Despite the ferocity of the assault, it’s likely that members of the Scandanavian group survived. The boat burials were done quickly, probably in just a few hours, but the bodies were treated with great care. The warrior who lost an arm even had his severed limb placed next to him. The priceless swords were ceremonially bent, and valuable grave goods were left in the ships. So who exactly were the Salme bodies? We don’t know, although later Norse sagas claim that the legendary king Ingvar was overwhelmed by a powerful force of Estonians while raiding there. However, Salme wasn’t a heavily settled area at the time, leading archaeologists to question why anyone would bother raiding it. It has even been suggested that the raiding party might have encountered a rival group at sea, leading to a fierce ship-to-ship battle. Perhaps the raiders slipped away from their enemy and briefly landed on Osel’s isolated shore to bury their fallen comrades.

6The Bronze Warrior’s Last Fight

In 1989, a 4,000-year-old skeleton was unearthed near the village of Racton in Sussex. Swinging into action, British archaeologists promptly left it in storage for 23 years. Then, a chance comment led to an examination by Bronze Age metalwork expert Stuart Needham, who realized that the corpse had been buried with perhaps the oldest bronze object ever found in Britain—a magnificent dagger. With research funding secured, we now know a great deal more about the dagger and the dramatic death of its owner. “Racton Man,” as he was soon dubbed, was around 1.8 meters (6 ft) tall, making him a giant for his time. He also lived a long life for the period, reaching the ripe old age of 45. He was clearly a fighter (he had an old sword injury to one shoulder) and must have been a powerful figure to own a beautiful weapon like the dagger. A significant improvement over the copper weapons common in Britain at the time, it was sharpened to a deadly edge and would have gleamed in the sunlight when new. Interestingly, analysis of Racton Man’s teeth indicate that he wasn’t raised near Racton but probably came from further west, toward the West Country or even Ireland. But he seems to have been buried with respect and care, suggesting that he wasn’t a raider or a stranger to the area. We know so little about Bronze Age Britain that it’s impossible to say why Racton Man might have traveled from his home or what adventures he might have had along the way. Certainly, his age was beginning to catch up with him. His bones show signs of spinal degeneration and arthritis, and he seems to have had a chronic back problem. Perhaps his age betrayed the old fighter when faced with a younger opponent. In any case, Racton Man seems to have died in combat. There are clear signs of a brutal cut to his upper right arm, probably sustained when he raised his hand to try to deflect a blade. This wound shows no signs of healing, indicating that it happened immediately before his death. The same blow might have severed an artery in his armpit, although it’s hard to be sure from the surviving remains. He was buried shortly afterward, holding his precious dagger clasped in front of his face.

5The Cowboy Wash Massacre

In the 1150s, a small community of 65–120 people lived in a scattered settlement around Cowboy Wash, near the Ute Mountain in what is now Colorado. The settlement was only about 15–20 years old, and the style of pottery found there suggests that the inhabitants were immigrants from the Chuska Mountains. Since the settlement’s pit houses were all built at roughly the same time, the Chuskans probably arrived as a group, perhaps seeking relief from drought and crop failure in their homeland. Less than a generation later, something terrible happened at Cowboy Wash. Archaeologists excavating the site found bones everywhere, all bearing the marks of cutting tools and careful butchering. Many bones had been broken at the ends, as if to get at the marrow. Others had been carefully broken into pieces small enough to fit into cooking pots. Discoloration suggests that they were stewed. Other bones bore scorch marks consistent with body parts being roasted. Cracks and scorch marks on two skulls suggest that they were cooked on hot coals and then cracked open to get at the brains. Fossilized human feces found nearby tested positive for myoglobin, indicating cannibalism. Tests also detected an acidic protein found only in human brains. They did not detect any plant matter. A cooking vessel found at the site also tested positive for myoglobin. Human blood was detected on stone cutting tools left in the houses. Since the deaths coincided with one of the most devastating droughts in the history of the Southwestern US, it was initially speculated that hunger had driven the Canyon Wash people to eat the dead. But hunger-induced cannibalism doesn’t fit with the terrifying intensity of the Cowboy Wash cannibalism. All of the bodies were apparently cooked and eaten in only a day or two, requiring the hearths to be cleared of ash several times. The eaters of the dead even crudely expanded one hearth so that more meat could be packed in. The skulls were mutilated far more than would be required for consumption. Was the settlement attacked by unknown raiders? Valuables were left lying around, suggesting that profit couldn’t have been the motive. The settlement was abandoned immediately after the murders, suggesting that the Cowboy Wash people either all died or felt unable to retrieve their belongings before fleeing. Archaeologist Brian Billman, who excavated the site, has observed that the Cowboy Wash tragedy wasn’t an isolated incident. Instead, it was part of a wave of “terroristic violence” that swept across the region between 1150 and 1175. The attacks wiped out entire settlements, leaving only mutilated remains. Yet before 1150, the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest lived a remarkably peaceful existence, with violence almost unknown. There are a number of theories to explain the attacks, including an unsubstantiated suggestion that a group of Toltec cultists had brought their violent religion north from Mesoamerica. For his part, Billman notes that tree cores show that the great drought of the 1100s was beyond anything the Pueblo people had experienced. Life in the region had always been hard, but the many Pueblo groups had survived thanks to a strong tradition of generosity, which encouraged communities to help each other out. But as the great drought wore on and on, prompting waves of migration like the one that brought the Chuska to Cowboy Wash, these bonds were stretched to the breaking point. As Billman put it: “What happened when things fell apart?”

4The Dark Side Of The Sun God

Dubbed “the first individual in human history,” Akhenaton is well-known as the pharaoh who briefly abandoned Egypt’s traditional polytheism, elevating the Sun god Aten above all other gods and making him the focus of all state religion. Together with his powerful wife, Nefertiti, Akhenaton oversaw sweeping changes in Egyptian art and architecture, climaxing in the building of a new capital at Amarna, dedicated to the worship of Aten. To make sure it would be free of the old gods, Akhenaton ordered it built in the middle of the desert. But enough about the pharaoh; what about the ordinary people who actually built Amarna? If you believe Akhenaton’s propaganda, their lives must have been great. The tombs of Amarna are covered with carvings of abundant food offerings to Aten. However, studies of human remains by archaeologist Gretchen Dabbs tell a different story. The ordinary people of Amarna were noticeably malnourished and had a high mortality rate for the time. Scurvy was shockingly common. A third of adults had spinal trauma (most commonly compression fractures), and almost half had degenerative joint disease, indicating the brutal toll of building a desert city from scratch in a short period. Protesting the conditions probably wasn’t a great idea, given the brutal punishments that the government liked to dole out. At least five skeletons in Amarna’s cemetery for commoners exhibit multiple stab wounds to their shoulder blades. This gels with a wall inscription announcing a punishment of “100 lashes and five wounds” for stealing hides. A stab to the shoulder blades would be extremely painful but not debilitating, allowing punished workers to get back to their jobs in no time. Such was the unspoken reality of Akhenaton’s new religion.

3Burying A Shaman

In the 1960s, Soviet archaeologists were excavating a Siberian burial site known as Ekven on the edge of the Arctic Circle when they uncovered a magnificent wooden mask, complete with staring eyes carved from bone. Recognizing the face from their own mythology, the local Yupik working on the dig almost refused to go on, believing it would bring terrible misfortune to disturb the grave of a shaman. Lead archaeologist D.A. Sergeev declared that he would take on the consequences himself and pressed on, excavating one of the most remarkable graves of the Old Bering culture, which thrived in the area some 2,000 years ago. The shaman died during the summer, when the Arctic permafrost had somewhat thawed. She was old (around 40–50 years) and probably passed away from natural causes. Her people hacked a deep grave into the soil, lining the floor with planks. The shaman was placed in the center with her ceremonial mask at her knees and surrounded by curved whale bones planted upright in the ground. The whale bones were also used to support a roof, which was lowered into place and then carefully covered with dirt. Boasting the power to communicate with the spirit world, the shaman must have been a particularly powerful woman, since the grave was packed full of objects precious to the Old Bering people. Many were tools typically used by men, and the sheer number suggests that the shaman couldn’t have owned them all in her lifetime. Instead, people probably came to offer their valuables for burial with the holy woman. Despite its remote location, Ekven was likely the center of a thriving trade in iron objects, so precious to the Bering people that the shaman was buried with walrus ivory carved into the shape of an iron chain. At some point, water seeped into her grave and then froze, helping to preserve the shaman and her priceless mask for the next two millennia.

2The True Story Of The Iceman’s Death

Otzi the Iceman is perhaps the most famous prehistoric body ever found. Perfectly preserved in an Alpine glacier, the Iceman has provided us with an incredible glimpse into life in the region 5,300 years ago. We even know his health problems—Lyme disease, tooth decay, gallstones, and arsenic poisoning from working with copper. As it turned out, Otzi didn’t have to worry about any of those, since he died in a violent confrontation involving an arrow to the shoulder and a blow to the head. Until recently, archaeologists suspected that his death had followed a daring chase through the mountains, with Otzi killing two of his pursuers before being hunted down, exhausted and starving, and brutally murdered. As it turns out, things didn’t go down quite like that. A breakthrough came when scientists realized that what they thought was Otzi’s empty stomach was actually part of his colon. His real stomach had been pushed upward under his ribs while he was in the ice. It was packed full of ibex meat, indicating that Otzi had eaten a large meal not more than an hour before his death. Clearly, the Iceman wasn’t in the middle of a dramatic chase if he decided to sit down and stuff himself full of venison. Further evidence came in 2015, when scientists used nanotechnology to detect a blood-clotting protein called fibrin on Otzi’s arrow wound. Since fibrin vanishes quickly in a working body, its presence proves that Otzi died very quickly after being shot, contrary to earlier theories that he survived the arrow wound for days. With the new evidence, we can now safely discard the chase theory of the Iceman’s death. Instead, it seems that Otzi felt safe in the mountains and sat down for a leisurely meal. However, shortly afterward, he was ambushed and shot. He also suffered a head injury, possibly because he fell after being shot. It’s not quite as dramatic as a deadly race against unknown pursuers, but at least we can now be reasonably sure of how the Iceman died.

1A Family Takes A Walk

Roughly 850,000 years ago, a small group of early humans walked along the mud flats beside an ancient river in what is now Norfolk, England. They were probably a family group, consisting of one or two adult men, two or three adult women or teenagers, and at least three young children. They were in no rush, meandering about as they collected shellfish, crabs, and seaweed from the riverbank. Watch this video on YouTube The group lived in a period where ice age conditions had temporarily abated, and the river valley was lush with greenery. Mammoths and early rhinoceroses grazed nearby, and the group must have been careful to steer clear of the hippos basking in the shallows. There were also hyenas, lions, and great saber-toothed cats lurking around, but the group didn’t appear to have felt particularly threatened near the river. For safety, they probably made their home on one of the islands in the estuary, wading ashore at low tide. They didn’t know how to make fire but had primitive flint knives and scrapers. Since winters could get cold, they might have worn clothes, and the scrapers suggest that they had at least some ability to work hides. The group’s walk beside the river was discovered in 2013, when coastal erosion revealed their footprints near the modern village of Happisburgh. Sadly, they were destroyed by the tides in only a few weeks, but archaeologists, working at breakneck speed, were able to collect casts and 3-D images before that happened. Analysis revealed that the footprints were the oldest found outside Africa. Since the two older African finds are far less extensive, the Happisburgh footprints might be the best insight into the daily lives of our most ancient ancestors.