10Map-Making

Early map-making was far from an exact science. Some of the earliest maps we have provide an interesting look into just what we thought about unexplored lands. The earliest map we have of the entire continent of Africa was done by Sebastian Munster—a German scholar and Hebrew professor—around 1554. He got his information from interviewing German scholars and immigrants, collecting and compiling different maps they carried into one. Before dying of the Black Plague, he was one of the most influential mapmakers of the day, and what his map of Africa included gives us an interesting look into just what people told him the continent was like. In the middle of the continent—where we now know the Sahara Desert lies—is a massive forest. South of that, in the area of what’s now Nigeria, is a drawing of a cyclops, meant to represent the mythical Monoculi tribe. The sources of the Nile are lakes in the Mountains of the Moon. Nestled in the valley of the rivers is the kingdom of Prester John, a Christian missionary whose mythical, magical land was the driving force behind many expeditions into Africa. Just north of Prester John’s supposed kingdom is Meroe, which was said to be the final resting place of ancient Nubian kings. There are also a handful of islands around the continent, and some of the rivers are surprisingly accurate, even though they would disappear off subsequent maps only to be re-discovered in the early 19th century.

9Henry The Navigator

The man who was almost single-handedly responsible for opening up exploration into Africa, and who allowed Portugal to start staking their claims on this newly discovered continent, never actually set sail on an expedition in his life. Henry the Navigator was the son of King John I of Portugal and Phillippa of Lancaster; his first foray into Africa happened before he was 21, when he was sent to drive the Spanish out of the northern African city of Cetua. Seeing a massive opportunity for Portugal to expand its territory, he organized the first school for sailors; in 1416, adventurous souls from all over the country could go to the School of Sagres and learn the finer points of exploration from mathematicians, map-makers, and astronomers. Just as important as the expansion of Portuguese territory was Henry’s desire to find Prester John’s mythical kingdom, which had eluded explorers for centuries. He also had to overcome something very, very powerful—sailors’ superstitions about what would happen to them if they ventured into the waters of southern Africa. According to one such superstition, sailing past Cape Bojador (in the present-day territory of Western Sahara) would send them into waters infested with sea monsters, where their entire ship would be eaten—but only after their skin turned black. Once they realized their fears were pure superstition, explorers began bringing back a wealth of treasures from the new lands. Ostriches, ostrich eggs, gold, and sealskin were only some of the finds—in the decades following Portuguese construction of a fort at the Bay of Argium, they would begin exporting African slaves to Europe.

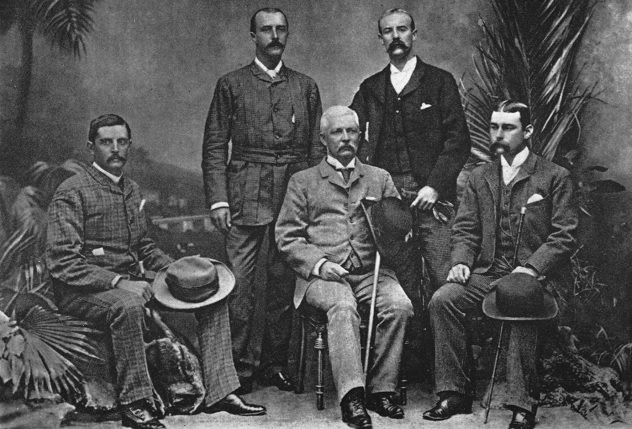

8Henry Stanley And Emin Pasha

Henry Stanley is perhaps best known for his expedition into Africa to find Dr. David Livingstone, but that’s not the only rescue mission he undertook. In December 1886, Stanley set off into Africa on what would be his last journey: an attempt to find and bring home a German zoologist named Eduard Schnitzer. Schnitzer had taken the name “Emin Pasha,” in an attempt to be better received by those he was living among. Pasha was cataloging a host of recently-discovered plant and animal lifeforms when fighting broke out in the Sudan. Pasha and his party retreated to Equatoria, at about the same time the Emin Pasha Relief Committee (pictured above) was formed. In addition to the goal of bringing Pasha home, Stanley was also under orders from the King of Belgium to open up some new trade routes in the area. The roundabout route the Committee ended up taking meant that by the time they finally found Pasha, many members of the expedition were dead. Those that did survive were worn, ill, and starving by the time they found Pasha who, in comparison, was well-dressed, clean, and—by some accounts—smoking a three-year-old cigar when they finally found him. He was in need of some support and supplies, but he had neither intent nor desire to leave the area. Arguments ensued, cementing a firm hatred between Stanley and Pasha. Stanley finally convinced Pasha to leave with the remains of the expedition, setting off on a grueling trip back through Africa. They finally met up with some German explorers, and made it back to the port town of Bagamoyo in 1889. During the party they threw to celebrate their return to civilization, Pasha fell off a balcony and fractured his skull. Stanley returned to Europe to commendations and congratulations, while Pasha slowly recovered from his unwanted rescue.

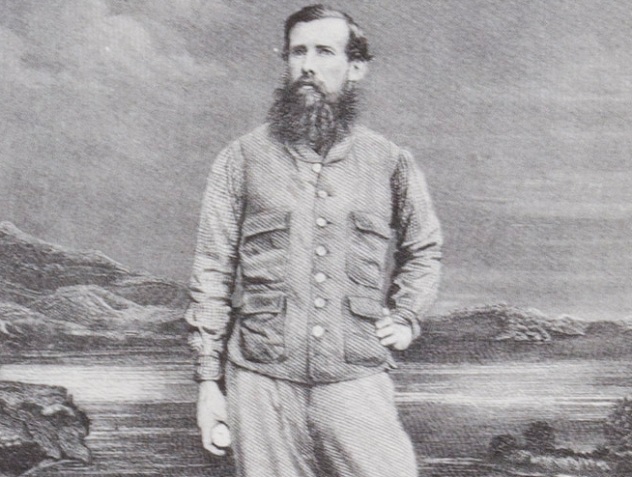

7 Paul du Chaillu And The Pygmies

Frenchman Paul du Chaillu was born in 1835. Raised on the west coast of Africa by his father, du Chaillu had the benefits of knowing many of the local languages, and he put his knowledge to good use. He is thought to be the first European to actually see a gorilla—until then, they had been regarded as mythical creatures. He was also the first to meet, interact with, and document the natives now known as Pygmies. Pygmies had existed in literature and letters for centuries but, like the gorilla, they were viewed as existing somewhere between the real world and the mythical one. Egyptian letters between traders dating back to 2276 B.C. call them the “dancing dwarf of the god from the land of spirits,” and they’re also featured in the Iliad, where they wage war on a flock of cranes. According to du Chaillu, his first impressions of Pygmies were of people who could move through the forest with incredible speed, grace, and silence. They amazed him with their perfect smallness, and he earned their trust through the presentation of food. His guides instructed him to always be kind to them, as they had always treated visitors with kindness and hospitality. Sadly, we did not hold onto that sentiment for long. By 1904, pygmies were being exhibited at fairs in St. Louis and the Bronx Zoo.

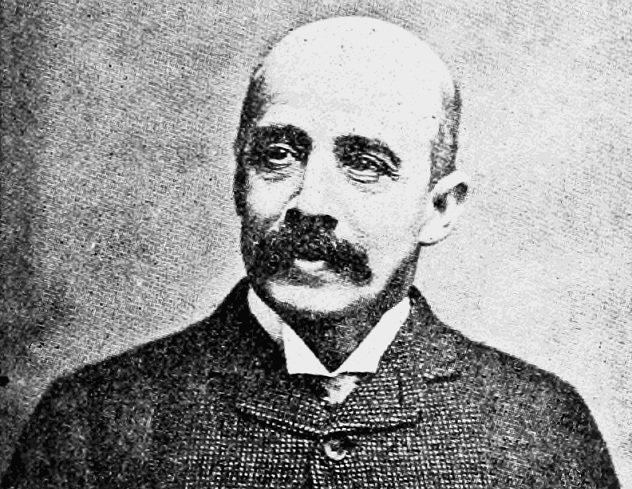

6The Hamitic Hypothesis

The exploration of Africa and slavery sadly go hand-in-hand, with the two impossible to separate. But there needed to be a justification for why enslaving the African people was perfectly acceptable. The Hamitic Hypothesis was just such an excuse. Even though the phrase “Hamitic Hypothesis” was only coined in 1959, the theory is often credited to John Hanning Speke (pictured), one of its most vocal supporters throughout the latter half of the 19th century. The theory said all things good and valuable in Africa had been brought there by the Hamites, or the descendants of Ham. According to Biblical tradition, Ham was cursed after he looked upon his naked father. The curse stated that he and his descendants would be the brothers of slaves—those descendants eventually made their way to Africa and became the lighter-skinned people of the northern continent. With them, it was thought, came education and civilization. They soon took up places of authority over the darker, lesser native people who were put on Earth to be slaves to the higher races. It was this tragically misguided hypothesis that, in large part, made it an acceptable thing to enslave African natives. Not only was it their lot in life, but any traces of civilization found there only existed thanks to the lighter-skinned people who migrated into the area.

5Robert Drury’s Mysterious Account Of Madagascar

Madagascar is one of the most exotic places on Earth, with natives and an ecosystem unlike anything found anywhere else. It’s mysterious even today, meaning it was downright scary in the early 1700s. Robert Drury’s tale of shipwreck, kidnap, bid for freedom, and return to Africa is a truly amazing one, and it didn’t end when he made his incredible escape from slavery and headed back to Europe. In 1729, Drury released a book, Madagascar: or Robert Drury’s Journal During 15 Years of Captivity on that Island, dramatically detailing the years he spent enslaved by the local people. If living through it wasn’t bad enough, no one believed it was real. It was released only a few years after Robinson Crusoe, which undoubtedly added a “you won’t fool us twice” factor to Drury’s tale. Drury died in 1735 (having spent his last years haunting coffee houses in London insisting to disbelievers that his tale was true), and it wasn’t until almost 275 years later that determined researchers discovered he had been telling the truth all along. British archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson decided to retrace the steps outlined in the book, to see if there was any truth to it. Pearson and his crew discovered the descriptions in the book were very, very accurate, from the locations of mountains and rivers to the towns Drury claimed to have lived in. There were also plenty of strangely specific details that only someone who lived there would know, like beekeeping techniques, ways of finding food, and cultural traditions (like feet-licking) that have since been phased out but have left their mark in the native lexicon. In addition, Pearson excavated villages and homes, examined tombs, and found that many of the native peoples still knew of ruined, extinct villages by the old names that Drury used. Ultimately, Pearson found the wreck of Drury’s ship, leaving only one major question unanswered. Critics had long argued that Drury—a largely uneducated sailor—couldn’t possibly have written the book himself, and wondered who the mystery author was. According to Pearson and other scholars, the likely author is the man responsible for most of the controversy in the first place: Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe.

4Mary Kingsley’s Study Of Witchcraft And Twin Killing

Mary Kingsley was born in 1862, into an English society that was very much about constricting women’s duties to nothing more than care of the household. At age 30, Kingsley lost both her parents to sudden illness. With nobody to care for, Kingsley decided she wanted to see the world she’d read so much about. So, she set off on a journey to West Africa. Her trip wasn’t just a sightseeing holiday, as she wanted to study the native people, their beliefs, and their religion—termed “fetish,” or “juju.” Amid her treks up and down mountains, through swamps, and down rivers, Kingsley recorded massive amounts of detail and data on the native people. While many of her observances sound savage and critical today, there’s one thing that stands out among the practices she was both amazed and horrified by: twin-killing. In some places, it was thought that a woman who gave birth to twins had been marked as having had intercourse with a demon or spirits, an offense that meant death for the mother and the babies. In other areas, twins were viewed as magical, and were to be kept alive and handled carefully. If one was to die, they would return for the souls of others. Kingsley bore witness to a horrific case of the former, where a slave-woman had given birth to twins and was quickly driven out of her village. The natives stuffed the poor children in a wooden chest and threw them to the mother. Unfortunately, one child died in the process, while the other made it out of town and to safety, thanks to a well-meaning missionary who took pity on the mother. When Kingsley returned to England to publish papers on those she had met and the things she had seen, she faced overwhelming resistance from polite society. Many places didn’t even allow her to speak in public, allowing her work to be presented only if it was read by a man. Eventually she returned to Africa, acting as a nurse during the Second Boer War. She died in 1900 from typhoid, but not before she brought a new level of enlightenment to European society.

3Diamonds, DeBeers, And A Secret Society

A single discovery by a 15-year-old South African boy playing with the rocks on his family farm in 1867 changed the face of his country forever. Erasmus Jacobs picked up a particularly shiny rock, and it caught the eye of a neighbor. That neighbor knew a traveling man who knew a little bit about everything, who took the rock to Hopetown. Someone there then passed it on to the Colonial Secretary, who sold it to the Governor of the Cape. It was the Eureka Diamond, a massive, yellowish diamond determined to be 21.19 carats. Enter Cecil Rhodes (pictured), both one of the most hated and most celebrated of all British statesmen. Rhodes (who would later found the Rhodes Scholarships), headed to South Africa and started buying diamond mines on the cheap, after the miners that had been working them thought their claims to the diamonds had run out. Rhodes then consolidated all the mines he owned—and those that he didn’t—into the Rhodes DeBeers Consolidated Mines. By the time he was done, he owned or controlled about 90 percent of the world’s diamond mines. He did this not just for personal wealth, but to help realize his dream of absolute British rule. Years before, he had written works outlining his goals of uniting the entire world under the eye of his Queen. While in South Africa, he took it upon himself to try and instigate rebellions that would lead to the installation of an English government. When he died, it took several wills to distribute his massive fortune. Many of his writings direct his fortune—amassed by kicking down the door of South Africa’s diamond mines—to be spent toward the development of a secret society. This society would be comprised of Britain’s richest and most powerful people, about whom he was often quoted as saying could do for England what Jesus did for the Catholics. Thus, his true intentions were made perfectly clear: He wanted his money to ultimately go toward advancing the British race, one he claimed was the greatest on Earth (the Americans and Germans could tag along, too.)

2Rene Caillie Enters Timbuktu

Timbuktu had long been surrounded by a certain mystique. Sitting on the edge of the Sahara Desert, this Muslim capital was long off-limits to non-Muslims. Because mankind hasn’t really changed that much over the centuries, that made it the place that Europeans absolutely wanted to see. Britain’s Gordon Laing was the first person to enter the city in 1826, but he was killed before he could make it far out again. After five weeks in the city, he was given permission to leave, but he was attacked, strangled, and decapitated on his way out (his personal servant lived to tell the story). Four years later, Rene Caillie, the son of a French baker, decided to give Timbuktu a go. He chose to do so without the typical retinue of soldiers, guards, and servants most explorers traveled with. Instead, he read and studied the Quran, learned Arabic, wore traditional dress, followed traditions and cultural norms, and went undercover as an Egyptian-born Arab. We can’t help but think that actually arriving in Timbuktu had to have been the biggest disappointment ever. Instead of an exotic city filled with strange people, beautiful animals, exotic spices, and archetypal walls made of solid gold, he encountered a small, muddy, desolate world. If he had made it there several centuries earlier, when the city was at its cultural peak, then his observations of the magical, mystical city might have been on par with his expectations (aside from the golden walls thing, obviously). Instead, he came away thinking everything there felt rather sad. He lived with a man named Sheikh Al Bekay while in the city, always keeping up his disguise even while being shown the house his predecessor lived in. His hosts were ultimately loath to let him leave the city, but eventually he did so, with more success than Laing. As disappointing a place as Timbuktu had been, making it back home still earned him the 10,000 francs promised by the French government to the first person to visit the city and make it back. Yet, Caillie still battled naysayers for the rest of his life, who argued that he never truly made it to the city. Perhaps they simply refused to believe that the beautiful golden city of legend was just a dreary place where people slept in doorways.

1Nathaniel Isaacs And The Wrongful Condemnation Of Shaka Zulu

Nathaniel Isaacs was born in Canterbury, England in 1808. By all accounts, he was destined for a life working in an office. He found the work stuffy and boring though, and ultimately ended up accepting a position on a ship called the Mary, captained by a man he’d made friends with. Upon finding out that another friend had journeyed into the uncharted territories of East Africa, they decided to go looking for him. The Mary was wrecked near Port Natal, and while she was salvageable, it would take three years to make her seaworthy again. During those three years, Isaacs and a handful of crew members made their way inland, where they were received by the Zulu warrior chief Shaka. The chief was not only friendly and welcoming to Isaacs and his companions, but after the Europeans joined with the Zulus during a raid and demonstrated the effectiveness of muskets, Shaka granted Isaacs a land claim. Later, Isaacs would publish his writings about his experiences and observances of the Zulu camps, in Travels and Adventures in Eastern Africa, published in 1836. For a long time, it was one of the most complete works written on Shaka and his successor, and it was considered one of the most authoritative sources on life in Eastern Africa. Only, it wasn’t all that true. Letters between Isaacs and one of his companions, Henry Francis Fynn (who was also writing a book about the Zulu), advised that embellishments be added in order to make their books more popular and sell more copies. While not all of the stories and legends of Shaka Zulu have been debunked, researchers from Rhodes University suggest that many of the bloodier stories about Shaka served another purpose: to popularize the idea that European settlers and explorers had the right to carve up the barbaric Africa into colonies. Stories were told of Shaka cutting apart pregnant women, murdering indiscriminately, and inventing new, brutal battle tactics. It’s since been shown that these “new” tactics were really hunting strategies that had been used for generations, and it’s unknown if Shaka ever had a formal army at all. Researchers know he was largely responsible for the Zulu rise to power in South Africa, but beyond that, Shaka Zulu is remaining stubbornly in the shadows of mystery.

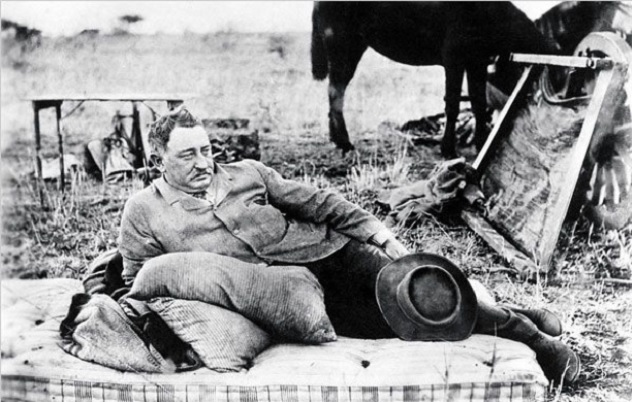

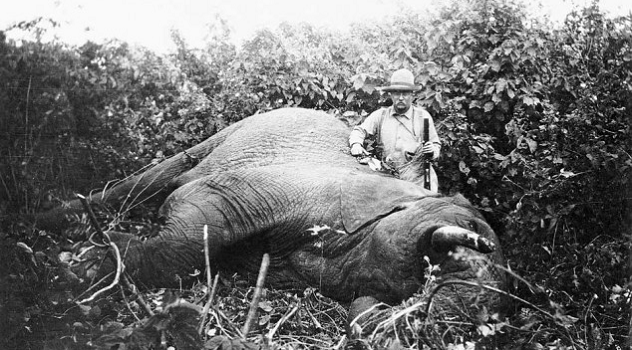

+Theodore Roosevelt And The Smithsonian’s African Expedition

Long after the Scramble for Africa, and even after our maps were pretty spot-on accurate, African expeditions didn’t stop. They simply turned into more scientific-minded endeavors, with goals of learning more about plant and animal life that previous explorers had skipped past in their attempts to get back home alive. In 1909, the Smithsonian Institution sponsored an expedition to collect both living and dead specimens for examination, cataloging, and inclusion in what’s now known as the National Museum of Natural History. Theodore Roosevelt—along with his son and a handful of representatives from the Smithsonian—left for Africa on March 23, 1909 to spearhead this project. Exploring the great unknown was a longtime passion of Roosevelt’s (plus, since he had recently stepped down from the United States presidency, he didn’t have much else to do), so he eagerly jumped on board. Roosevelt and company enjoyed a luxury earlier explorers could have only dreamed of: a railway journey into the heart of Africa. Once they assembled the various pieces of their force (which included 250 native-born porters and guides to help manage Roosevelt’s tent, bathtub, and library, along with several tons of salt for preserving whatever animals they found along the way), they embarked on a year-long tour of the continent. In the end, they had 23,151 specimens for the museum, including plants, insects, birds, and even live animals that were bound for the National Zoological Park. Even today, visitors to the National Museum can see the square-lipped rhinoceros that Roosevelt brought back. The American Museum of Natural History also has an exhibit that features Roosevelt’s kills—the elephants in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals. Interestingly, Roosevelt’s connection with the Smithsonian predates both his presidency and his explorations. While in his twenties, he donated his childhood collection of 250 mounted animals and birds that he had been collecting while traveling the world in his teens. Read More: Twitter