10 Pig Basket Massacre

After the Japanese occupied the Dutch East Indies, a group of about 200 British servicemen found themselves stuck in Java during the invasion. They took to the hills to fight as a guerrilla resistance force, but they were captured and tortured by the Kempeitai. According to over 60 eyewitnesses testifying at the Hague following the war, these men were then forced into 1-meter-long (3 ft) bamboo cages meant to transport pigs. They were then transported via trucks and open rail cars to the coast, in temperatures reaching 38 degrees Celsius (100 °F). The prisoners, already suffering from severe dehydration, were then placed on waiting boats, which sailed off the coast of Surabaya, whereupon the cages were thrown into the ocean. The prisoners were drowned or eaten alive by sharks. One Dutch witness, only 11 years old at the time, described the incident to a magazine: One day around noon, the hottest time of the day, a convoy of about four or five Army trucks passed the street where we were playing, loaded with so-called “pig baskets,” which were normally used to stack pigs during transport to the slaughterhouse or the market. Indonesia being a Moslem country, pigs were only for European and Chinese customers in the market. Moslems (Javanese) were not allowed to eat them and considered pigs (same as dogs) as “dirty animals” from which contact should be avoided. In other words: any connection with pigs and dogs was shameful. To our astonishment the pig baskets were crammed with Australian soldiers, some of them still wearing parts of their uniform, a few even their special hat. They were tied in pairs, two to each other, facing each other, and stacked, like pigs, in the baskets, lying down. Some were in a terrible state, crying for water, I saw one of the Japanese guards opening his fly and urinate on them. I remember being terrified and I can never forget this picture in my mind. Later my father told me the trucks were driven through the town as a show to the Indonesians for utter humiliation of the white race, finally being dumped into the harbour to drown. Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura, commander in chief of the Japanese forces in Java, was acquitted on war crimes charges by a Netherlands court due to lack of evidence but was later charged by an Australian military court and sentenced to 10 years in prison, which he served from 1946–54 in Sugamo, Japan.

9 Operation Sook Ching

After the Japanese captured Singapore, they renamed the city Syonan (“Light of the South”) and set the clocks to Tokyo time. They then initiated a program to clear the city of Chinese whom they considered dangerous or undesirable. Every Chinese male between the ages of 15 and 50 was ordered to report to registration points throughout the island for screening, where they would be closely questioned to determine their loyalties and political inclinations. Those who passed the tests were stamped on their face, arms, or clothing with the word “examined.” Those who failed the tests—communists, nationalists, secret society members, English speakers, civil servants, teachers, veterans, and criminals—were taken to holding areas. For many, simply having a decorative tattoo was enough to be branded as a member of an anti-Japanese secret society. For two weeks after the screening, those marked as undesirable were taken to be executed at plantations or coastal areas like Changi beach, Ponggol foreshore, and Tanah Merah Besar beach, where the bodies would be washed out to sea. Methods of execution varied according to the whims of four section commanders. Some were marched into the sea and then machine-gunned, while others were tied together before being shot, bayoneted, or decapitated. At later war crimes trials, the Japanese claimed that there were around 5,000 victims, while local estimates range from 20,000 to 50,000. Following the massacre, the Kempeitai maintained a rule of terror and torture, including a form of punishment in which a victim was forced to ingest water by fire hose and then kicked in the stomach. One administrator, Shinozaki Mamoru, was so horrified by the torture that he issued thousands of “good citizen” and safe passage passes, which were usually intended only for those collaborating with the Japanese. He issued almost 30,000 of them, saving many Chinese lives, much to the fury of the Kempeitai. He is remembered today as “Singapore’s Schindler.”

8 Sandakan Death Marches

The occupation of Borneo gave the Japanese access to valuable offshore oil fields, which they decided to protect by military airfield at the port of Sandakan with slave labor provided by prisoners of war. About 1,500 POWs, mostly Australians captured in the fall of Singapore, were sent to Sandakan, where they endured horrible conditions and meager rations of minimal vegetables and some dirty rice. They were later joined by British POWs in early 1943. The POWs were forced to labor on an airstrip while suffering from starvation, tropical ulcers, and malnutrition. Some early escapes led to a crackdown at the camp. POWs were beaten or imprisoned in open-air cages in the Sun for crimes such as collecting coconuts or failing to bow deeply enough to a passing camp guard. Those who were suspected of operating or building a radio or smuggling medicine into the camp were tortured by the Kempeitai, who burned their flesh with cigarette lighters or drove metal tacks into their nails. One victim would later describe the Kempeitai methods: The interviewer produced a small piece of wood like a meat skewer, pushed that into my left ear, and tapped it in with a small hammer. I think I fainted some time after it went through the drum. I remember the last excruciating sort of pain, and I must have gone out for some time because I was revived with a bucket of water. Eventually it healed but of course I couldn’t hear with it. I have never been able to hear since. In spite of the crackdown, one Australian soldier, Captain L.C. Matthews, was able to organize an underground intelligence ring, smuggle medical supplies, food, and money to prisoners, and maintain radio contact with the Allies. He refused to reveal the names of those who helped him, despite being arrested and tortured. He was executed by the Kempeitai in 1944. In January 1945, the Allies bombed the Sandakan air base, and the Japanese decided to withdraw inland to Ranau. Three death marches occurred between January and May. The first wave consisted of those considered most fit, who were loaded down with Japanese equipment and ammunition and forced to march through the tropical jungle for nine days, with only four days’ rations of rice, dried fish, and salt. Those who collapsed or faltered were shot or beaten to death by the Japanese, and when the survivors arrived, they were forced to build a camp. Those left behind at Sandakan suffered malnutrition and abuse and were eventually marched south in two further waves, with those unable to move left to die as the camp was torched in the Japanese withdrawal. Only six Australians survived the death marches.

7 Kikosaku

During their occupation of the Dutch East Indies, the Japanese had considerable difficulty controlling the Eurasian population, individuals of mixed Dutch and Indonesian blood who were often in positions of influence and disinclined to support the Japanese version of Pan-Asianism. They responded with severe repression and execution, which they referred to as kikosaku. The word kikosaku was a neologism which combined a derivative of the word kosen, a Buddhist reference to the land of the dead called “yellow spring,” and the word saku, meaning “engineering” or “maneuvering.” It has been translated into English as “Operation Hades” or “hellcraft.” In practice, it referred to executions without trial or extrajudicial punishments that caused death. The Japanese believed that the mixed-blood Indonesians, whom they referred to with the derogatory term kontetsu, had loyalty to the Netherlands. They suspected them of espionage and sabotage. They also shared the Dutch colonialists’ fears of communist or Islamic insurgency. They came to believe that following judicial procedure in investigating cases dealing with the disloyal was inefficient and impeded the administration. Instituting the policy of kikosaku allowed the Kempeitai to imprison people indefinitely without formal charge or subject those under suspicion to summary execution. Kikosaku was used when the Kempeitai believed only the most extreme of interrogation methods would lead to a confession, even if death was a result. A former member of the Kempeitai would later tell the New York Times: “Even crying babies would shut up at the mention of the Kempeitai. Everybody was afraid of us. The word was that prisoners would enter by the front gate but leave by the back gate, as corpses.”

6 Jesselton Revolt

The city now known as Kota Kinabalu was founded as Jesselton in 1899 by the British North Borneo Company and served as a way station and source of rubber until it was captured by the Japanese in January 1942 and renamed Api. On October 9, 1943, an uprising of ethnic Chinese and native Suluks assaulted the Japanese Military Administration, attacking Japanese offices, police stations, military hotels, warehouses, and the main wharf. Despite being armed with only a few hunting rifles, spears, and long parang knives, the rebels were able to kill 60–90 Japanese and Taiwanese occupying the city and surrounding towns before retreating into the hills. Two army companies and the Kempeitai were sent to initiate vicious reprisals, which were aimed not just at the rebels, but also the population at large. Hundreds of ethnic Chinese were executed simply for being suspected of aiding or supporting the rebels. They also targeted the Suluk natives on the offshore islands of Sulug, Udar, Dinawan, Mantanani, and Mengalum. The entire male population of the island of Dinawan was annihilated, while the women and children were forcibly moved elsewhere. Similar massacres took place on Suluk and Udar. While the Japanese estimated that only 500 died, others gave a number closer to 3,000, and the treatment of the Suluks in particular has been described by some as genocidal.

5 Double Tenth Incident

In October 1943, a group of Anglo-Australian commandos called Special Z infiltrated Singapore harbor using an old fishing boat and folding canoes. They placed limpet mines that sank or disabled seven Japanese vessels, including an oil tanker. They slipped out without being seen, so the Japanese became convinced that the attack had been orchestrated by British guerrillas out of Malaya, acting on information passed to them by civilians and inmates of the Changi prison. On October 10, the Kempeitai raided the prison, conducted a day-long search for evidence, and arrested suspects. Further inspections saw 57 of the internees arrested for involvement with the harbor sabotage, including an Anglican bishop and a former British colonial secretary and information officer. They would spend the next five months crammed together in cells that were always brightly lit without bedding or room to lie down, as well as being subjected to starvation and brutal interrogation. One suspect was executed for supposed connection to the sabotage, while 15 others ultimately died due to Kempeitai torture. During the 1946 trial of those involved in what became known as the Double Tenth incident, British prosecutor Lieutenant Colonel Colin Sleeman described the Japanese mentality of the time: It is with no little diffidence and misgiving that I approach my description of the facts and events in this case. To give an accurate description of the misdeeds of these men, it would be necessary for me to describe actions which plum the very depths of human depravity and degradation. The keynote of the whole of this case can be epitomized by two words—unspeakable horror. Horror stark and naked permeates every corner and angle of this case from beginning to end, devoid of relief or palliation. I have searched, I have searched diligently amongst a vast mass of evidence to discover some redeeming feature, some mitigating factor in the conduct of these men which would elevate the story from the level of pure horror and bestiality and ennoble it, at least upon the plane of tragedy. I confess I have failed.

4 Bridge House

The Kempeitai had kept a presence in Shanghai since the Imperial Japanese Army occupied the city in 1937, and the secret police were headquartered in a building known as Bridge House. Shanghai’s foreign presence and intellectual culture saw the rise of resistance publications against the Japanese. The Kempeitai and the collaborationist Reformed Government used a paramilitary organization made up of Chinese criminals called the Huangdao hui (Yellow Way Organization) to commit murders and terrorist actions against anti-Japanese elements in foreign settlements. In one notable incident, Cai Diaotu, editor of an anti-Japanese tabloid, was beheaded, and his head was strung up from a lamppost in front of the French Concession with a placard reading, “Look! Look! The result of anti-Japanese elements.” After Japan’s entry into World War II, the Kempeitai were turned loose against Shanghai’s foreign population, who were arrested on charges of anti-Japanese activity or espionage and transported to Bridge House, where they were imprisoned in steel cages and subjected to beatings and torture. Conditions were awful: “Rats and disease-infested lice were everywhere, and no-one was allowed to bathe or shower, so diseases from dysentery to typhus and leprosy ran rampant.” The Kempeitai reserved particular attention for British or American journalists who had reported on Japanese atrocities in China. John B. Powell, the editor of the China Weekly Review, was a typical case of the treatment meted out to prisoners: “When the questioning began, they had to remove all their clothing and kneel before their captors. When their answers failed to satisfy their interrogators, the victims were beaten on the back and legs with four-foot bamboo sticks until blood flowed.” Powell was repatriated but died following the amputation of a gangrenous leg, and many other reporters were permanently injured or driven insane by the treatment. In 1942, a number of Allied civilians who were tortured at Bridge House were released as part of a repatriation deal brokered through the Swiss embassy. The journey was made deliberately unpleasant by the Japanese. The internees were placed belowdecks in overcrowded, sweltering conditions as the ship picked up more internees from Yokohama and Hong Kong and then made its slow and grueling journey to the neutral Portuguese port of Lourenco Marques in Mozambique.

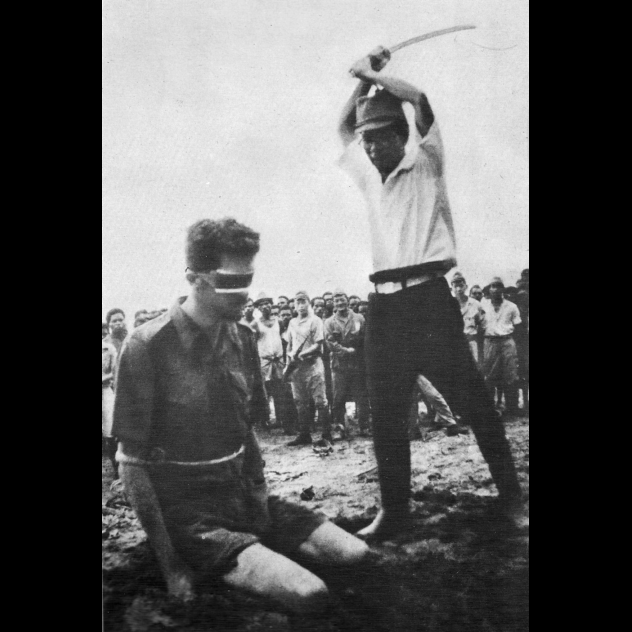

3 Occupation Of Guam

Along with the Alaskan islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians (whose population was evacuated before invasion), Guam was the only populated territory of the United States occupied by the Japanese during World War II. Seized in 1941, the island was renamed Omiya Jime (Great Shrine Island), while the capital Agana was renamed Akashi (Red City). The island was initially under the supervision of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Keibitai. The Japanese used vicious methods to try to remove all American influences and force the native Chamorro people to adhere to Japanese social mores and customs, in the hope of making them into pliant citizens of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Kempeitai took control of the island in 1944, as the war was turning against the Japanese and the American war machine was barreling across the Pacific Ocean. Forced labor for Chamorro men, which had been in place since 1943, was expanded to include women, children, and elders. The Kempeitai were convinced that the pro-American Chamorros were engaging in espionage and sabotage and cracked down harshly on the population. Civilians were raped, shot, or beheaded by the military police as discipline broke down. One man, Jose Lizama Charfauros, bumped into a Japanese patrol while foraging for food and was forced to kneel down before being chopped in the neck with a sword. He was found by friends days later; maggots had entered his wounds and kept him alive by clearing out infection. He survived the war with a massive scar on his neck.

2 Comfort Women

The issue of “comfort women,” who were forced into prostituted slavery by the Japanese military during World War II, is still a cause for political tension and historical revisionism in East Asia, and it has a long history. Officially, the Kempeitai were placed in charge of organized prostitution from 1904 onward. Initially, brothels were subcontracted with the military police, who were placed in a supervisory role based on the possibility that some of the prostitutes could be spies fishing for military secrets from talkative or careless clients. In 1932, the Kempeitai took complete control of organized prostitution for the military, building military brothels with barracks or tents used to house women who were forced into service. They were imprisoned behind barbed wire and guarded by Japanese or Korean yakuza. Railway cars were also used as mobile brothels. Girls as young as 13 years old were forced into prostitution, with prices varying depending on ethnic origin and whether the clients were commissioned officers, noncommissioned officers, or privates. Japanese women fetched the highest fees, followed by Koreans, Okinawans, Chinese, and Southeast Asians. Caucasian women were also forced into service during the war. It is believed that up to 200,000 women were forced to sexually service up to 3.5 million Japanese soldiers. The women were kept in appalling conditions and received little to no money, despite being promised 800 yen a month for their “service.” There are still many questions about Japan’s use of comfort women, as there was a great degree of secrecy, as well as destruction of evidence. In 1945, the British Royal Marines captured Kempeitai documents in Taiwan that detailed how the prisoners were to be dealt with in the case of an emergency: Whether they are destroyed individually or in groups, or however it is done, with mass bombing, poisonous smoke, drowning, decapitation, or what . . . it is the aim not to allow the escape of a single one, to annihilate them all and not to leave any traces.

1 Epidemic Prevention Department

While it is widely known that the Japanese engaged in human experimentation through Unit 731, the scale of the program is often not entirely appreciated, and the existence of 17 other related facilities throughout Asia is usually unknown. The Kempeitai was placed in charge of the Unit 173 facility in the Manchurian city of Pingfan. Eight villages were razed to allow the construction of the facilities, which included living quarters and facilities for thousands of researchers and medics, as well as Kempeitai barracks, a prison camp, underground labs and bunkers, and a large crematorium to dispose of bodies. The Orwellian expression used to describe the body in charge of facilities and others was “Epidemic Prevention Department.” Shiro Ishii was the man in charge, and he introduced his staff to the center by saying, “A doctor’s God-given mission is to block and treat disease, but the work on which we are now to embark is the complete opposite of those principles.” Prisoners who were sent to the Pingfan facility were usually those who had been earmarked as “incorrigible,” “die-hard anti-Japanese,” or “of no value or use.” The majority were Chinese, but there were also Koreans, White Russians, and later Allied POWs from the United States, the UK, and Australia. The Japanese staff referred to the prisoners as murata (“logs”) and referred to the Pingfan facilities as a lumber mill. These facilities used live human subjects to test the effects of biological and chemical weapons, as well as exposure to diseases like bubonic plague, cholera, anthrax, tuberculosis, and typhoid. Live vivisections without anesthetic were also common. One researcher new to the facilities described the process used on a 30-year-old Chinese male: The fellow knew that it was over for him, and so he didn’t struggle when they led him into the room and tied him down. But when I picked up the scalpel, that’s when he began screaming. I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then he finally stopped. This was all in a day’s work for the surgeons, but it really left an impression on me because it was my first time. Other facilities supervised by the Kempeitai and the Kwantung Army were present in other parts of China and the rest of Asia. Unit 100 in Changchun developed vaccines for Japanese livestock and biological weapons to decimate Chinese and Soviet livestock, while Unit 8604 in Guangzhou bred rats designed to carry bubonic plague. Other facilities to research malaria and plague were established in Singapore and Thailand, though many records were destroyed before they could be captured by the Allies. David Tormsen can be contacted at [email protected].