The fashion for hiring “male midwives,” also known as accoucheurs, to attend middle and upper class ladies in labor often proved deadly, as did the new “lying-in” hospitals. Because doctors went to their patients with their sleeves clotted with another patient’s blood, their hands unwashed, and a placenta or two in their coat pockets, women frequently succumbed to childbed or puerperal fever, an infection of the uterus causing a drawn out, agonizing death. Up to nine women in a hundred were infected, as many as three of them dying from septicemia. While some physicians noted the connection between simple hand washing and reduced rates of puerperal fever, many others rejected the theory.

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, a husband, father, or other male authority figure could—and did—have a woman declared insane as easily as getting two doctors to sign the certificate, and they didn’t even have to see the patient. A man’s testimony was enough to get a female relative locked up in secret indefinitely. Some women suffered from “puerperal insanity,” or post partem depression and other mental illnesses, but others were imprisoned in an asylum for no greater cause than disagreement with established norms (such as declaring women should get the vote), a medical condition like epilepsy, the ever popular hysteria, or infidelity. Treatments were crude at best, cruel at worst. Doctors considered female patients in danger of developing “erotomania” or hypersexuality, and took steps accordingly.

Married women prior to 1870 had no control over their own property, wages, money, inheritance, etc. Even a valuable gift became her husband’s property, and she had no legal recourse if he abused “their” assets. Women couldn’t buy or sell any property or business of any kind in their own name. From a legal standpoint, a woman owned nothing, not even the clothes on her back. Any dowries paid to the husband by his bride’s relatives could be specified for her own use by a prenuptial contract if the fiancé agreed. Until the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act in 1870 and 1884 in Britain established a wife’s rights in law, the only way to avoid being impoverished by an errant or corrupt spouse was to remain single. It would take until 1900 before all U.S. states passed similar laws.

Until 1925 in Britain, in the case of someone dying intestate (without a will), a female heir could not inherit any “real” property, like valuable land, as long as there was a male heir. Instead, the law limited such women to personal property like jewelry, furniture or clothing. If the property was entailed—that is, legally bound in a specific way—then only a male heir could inherit, even if that heir was a very distant relative of the deceased. Often, if a woman was lucky enough to inherit something very valuable like an estate or investments, the inheritance was controlled by a (male) trustee, who decided how/when the female beneficiary received any benefits. Unless, of course, she was married. See #8.

Early in the nineteenth century, divorce in England could be obtained only by an Act of Parliament. Later, a man could divorce his wife on the grounds of infidelity. But what about a wife if her husband proved vicious, abusive, and violent? In 1853, the British government passed a law setting up legal limits to the amount of force a man could use against his wife (not banning the abuse, mind you, just outlining boundaries for abusers). Even if a woman managed to obtain a divorce (though for her, only on the grounds of cruelty, incest, abandonment, or bigamy in addition to infidelity), she was left destitute. Worse, courts preferred to award custody of children to the husband until around 1878.

Well into the twentieth century, women were disregarded to the extent that legally speaking, they were non-persons. A woman couldn’t a open bank account in her own name, purchase any form of birth control, vote, sue someone in court, sign contracts, or make her own medical decisions. She wasn’t supposed to have sexual contact with a man other than her husband (rape was seen as the woman’s fault). Educational opportunities were minimal, even for the upper class. Women were supposed to take care of the household, bear children, obey social restrictions, and do very little else. Physical activity was frowned upon. For example, some physicians publicly spoke out against the dangers of the pernicious bicycle, which they feared might cause women to become “oversexed” because they straddled the saddle.

By the 1860s, the British government had suddenly realized that many of their soldiers and sailors suffered from venereal diseases like syphilis. In response, in 1864, the first attempt at regulating prostitution was passed as the Contagious Diseases Prevention Act. The law was directed solely at women. In a nutshell, any woman suspected of being a prostitute was required to submit to a physical examination. No warrant was required. Any woman in public, be she twelve years old or eighty, whom police thought might be selling sexual favors, whether they had evidence or not (for instance, just on the dodgy testimony of a jealous boyfriend), could be seized, taken to a police station, and forced to endure what amounted to painful sexual assault while a male policeman “examined’ her private parts! It’s worth noting that it was working class and poor women who generally suffered under these unfair laws.

The Victorian era offered few employment opportunities for women. For upper and middle class ladies, going to work wasn’t even a consideration. Lower class women who had to support themselves and/or children and other family members were limited mostly to factories or sweatshops, domestic service, home industries like shirt sewing or paper flower making that paid a starvation wage – or prostitution. At one point, prostitution was so rife that in London alone, it was estimated as many as one in nine women sold herself to earn a living. Legitimate employment in a factory wasn’t that much better. Workers endured long hours, dangerous conditions, few health or safety protections under the law, and unfair wages.

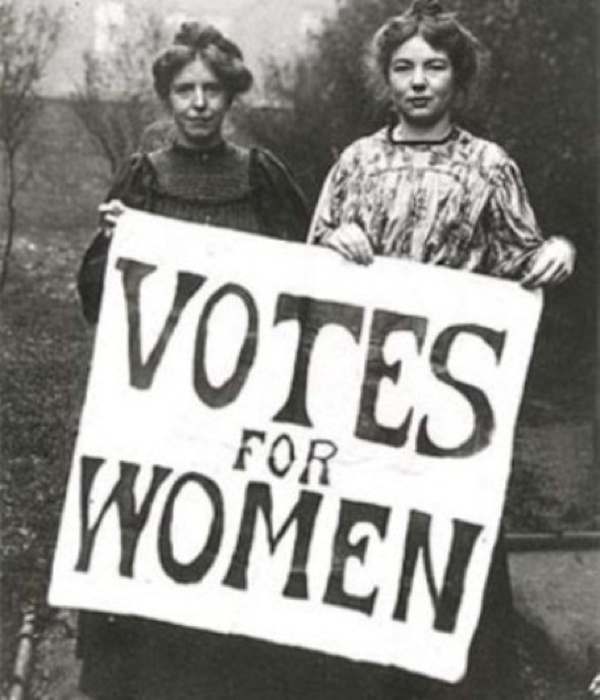

Unsurprisingly, nineteenth century men used a variety of rationales to deny women the vote. Anti-suffragette propaganda was denigrating, to say the least. Among the arguments used were that women weren’t interested in politics, men were mentally better suited to understanding the complexities of political issues, women were emotionally unstable, a woman’s place was in the home, participation in public activities like voting went against feminine modesty, etc. When suffragettes went on hunger strikes after being arrested, they were strapped down and force fed on the order of the authorities. This may sound like a simple medical procedure, but it was a horrific violation and a nightmarish experience.

In the latter party of the nineteenth century, a series of articles in a British newspaper shocked Victorian society to the core. An investigative journalist discovered how easy and cheap it was to buy a female child for sexual purposes—₤5 was the going rate. It seemed wealthy male purchasers delighted in deflowering young virgins and would pay for the privilege. Brothel keepers in major cities bought adolescent girls as young as twelve or thirteen years old from impoverished families and put them to work, which usually began a life of sexual degradation and slavery. Corrupt police and clergymen looked the other way until W. T. Stead broke the story, calling it the Maiden Tribute of a Modern Babylon. As you see, ladies put up with a lot in the nineteenth century. Women have gained some ground in first world countries since then – gained some rights – but somehow, full equality remains elusive in the 21st century. Read More: Facebook