10 Whirling Logs

Similar in design to the swastika, a symbol known as the “whirling log” has been used by Native Americans in the US Southwest for centuries, dating back to at least the time of the mysterious and ancient Anasazi. In Navajo myth, the symbol depicts the tale of the whirling log (or “Tsil-ol-ni”), in which an outcast faces troubling times as he travels down a river in a hollow log. At the end of his journey, he reaches a land of plenty and prosperity. In some cultures, the whirling log was believed to represent the four winds or the four directions. This symbol only appeared in religious ceremonies until 1896, when it emerged as a design for Navajo rugs and spoons. The symbol was adopted by nonnatives as a good luck symbol in the early 20th century, by a New Mexico coal mining company, and by the University of New Mexico, which published a yearbook called The Swastika. After World War II broke out, the Navajo, Apache, Tohono O’odham, and Hopi tribes resolved to abandon the use of the symbol on blankets, baskets, art objects, sandpainting, and clothing because of the association with Nazi evil. In recent years, there has been a movement to reclaim the use of the design as a Native American symbol.

9 Gammadion

One ancient Greek symbol closely resembling the swastika was known as “gammadion,” or “crux gammata” (the cross with gammas). It resembled four Greek capital letters of gamma placed together, so their corners formed a common center. Some early Christians used the gammadion to represent the cross of Christ. It was also used as a secret symbol during the period when the Roman Empire persecuted Christians. Known as “crux dissimulata,” these secret symbols included the swastika, axe, anchor, and trident. Some say the symbol represented Christ as the cornerstone of the church, or it was used to protect the spirits of the dead in catacombs. Long before the rise of Christianity, the gammadion was a common motif for Mediterranean civilizations such as the ancient Minoans, Greeks, and Etruscans, linked to Sun worship and labyrinths. It was quickly co-opted by the early Christians, appearing on shrines, priests’ clothing, and even representations of Jesus Christ. Some even see this as evidence the Christian faith was ultimately derived from the teachings of Indian religions, though this seems unlikely.

8 Wan

In Buddhism, the swastika (called wan in Chinese and manji in Japanese) is an important religious symbol, meaning resignation of spirit. Swastikas of various colors are said to have differing meanings: Blue represents heaven’s eternal benevolence, red is the Buddha’s limitless benevolence, yellow stands for infinite prosperity, and green designates limitless cultivation. A left-facing form of the swastika is believed to be the first of 65 auspicious symbols which appeared on the footprint of the Buddha, while a right-facing version was the fourth such symbol. The swastika is sometimes considered the seal of the Buddha’s heart and may appear on the chest, forehead, palm, or foot of representations of the Buddha. Some believe the Buddhist swastika symbol originated from the shape of the characters for the word “sv-asti” in a new alphabet devised by Buddhist Emperor Ashoka or from the shape of the early Buddhist Pali symbols for “su” and “ti,” derived from Sanskrit words meaning “well” and “it is.” In the Tibetan Bon tradition, the swastika is called gyung-drung (meaning “eternal and unchanging“). Unlike other swastikas of the Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions, the Bon swastika is counterclockwise, which is why Bon pilgrims circumambulate sacred sites in a counterclockwise direction. In Chinese, the swastika is referred to as the “ten thousand” character and is believed to have come down from heaven. It was standardized as a Chinese character, meaning “myriad,” with the same pronunciation as the character meaning “ten thousand.” While rarely used, both clockwise and counterclockwise variants are usually included in character dictionaries, and both have been encoded into Unicode. The symbol was often used at the beginning of Buddhist texts in both China and Japan. In Japan, the character is often used on maps to indicate a Buddhist temple.

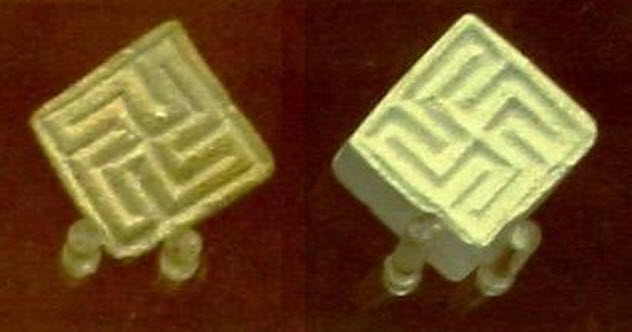

7 Gahuli

The traditional symbol of the Jain faith was the swastika, known as “Gahuli” or “Ghaunli,” which usually was represented with four dots. These dots represented the four different fates which befall every soul over multiple lives depending on their deeds and karma: life as a human, an animal, a divine being, and a hellish being. The swastika itself has multiple meanings. It represents a wheel, suggesting an eternal nature of material existence. The four arms represent the four branches of the Jain faith: sadhus (monks), sadhvis (nuns), shravaks (male householders), and shravikas (female householders). The symbol reminds Jains their goal should be liberation from reality and not rebirth into it, which can only be achieved through these four pillars of the Jain community. The arms also represent four eternal characteristics of the soul: knowledge, perception, happiness, and energy. The symbol chosen to represent the Jain community incorporates the swastika, an outstretched hand inscribed with “Ahimsa” (meaning “not to injure”) on the palm and three dots above the swastika representing the three jewels of Jainism: Samyak Darshan (Right Faith), Samyak Jnan (Right Knowledge), and Samyak Charitra (Right Conduct). At the top of the symbol is a curved arc with a dot, representing a liberated soul at its final destination. The overall outline represents the universe: the seven hells, the Earth and planets, and the heavenly abodes. In Europe and North America, Jains aware of the negative meaning attributed to the swastika replace it with another symbol, such as the holy word “Om.”

6 Swasti

In the Vedic tradition of ancient Hinduism, the word swastika derives from the root word “swasti,” meaning “let good things happen” or “well-being.” It was generally a word used to indicate wellness and auspiciousness, used as an adjective or noun and incorporated into rituals, names, and expressions of farewell and congratulations. Its origins are believed to lie in the Sun worship religion of the Indus Valley civilization, but it was incorporated in a variety of ways into the developing Hindu faith. The swastika is said to represent the creator god Brahman in his two manifestations: the evolution of the universe when the symbol faces right, universal involution (turning inward toward God) when it faces left. The clockwise swastika is the one more commonly used by Hindus, while the counterclockwise swastika is associated with Tantra (and regrettably, Nazism). The Hindu swastika’s four limbs have many meanings: the Four Vedas, the four goals of life (meaning prosperity), the four stages of life (meaning good fortune), the four directions in space (meaning the omnipresence of Brahma), the four seasons (meaning time’s cyclic nature), and the four Yugas of the world cycle (meaning the natural evolution of the universe). The swastika is closely associated with the god Ganesha, often depicted sitting on a lotus flower above a bed of swastikas. It is also a symbol of the goddess Lakshmi and variously represents luck, a meeting point of four roads where commerce occurs, a tantric sitting posture, crossed arms in front of the upper body, a building plan, a design made with rice for rituals, a kind of cake, a happy and free-spirited woman, and garlic.

5 Hakaristi

The swastika, known as hakaristi in Finnish, has been considered a good luck symbol in Scandinavia and the Baltic region for thousands of years, appearing on pottery and runes. Swedish nobleman Count Erik von Rosen adopted the symbol as a personal good luck symbol, even marking his luggage with a swastika while traveling in South America and Africa. After Finland declared its independence during the Russian Civil War, Rosen gifted the fledgling country with its first military aircraft, a single-engine ski-plane with a swastika symbol. In 1918, a straightened blue swastika on a white background was adopted as the official symbol of the Finnish air force. The symbol was well liked in Finland and became popular on jewelry and heraldry. The symbol was used on Finnish aircraft until the end of World War II. After that, the swastika was mostly banned, although it was revived on some flags in 1957. In 2007, a Finnish charity began to sell rings engraved with swastikas with stylized wings, replicas of the 1940 “Air Defense” ring, to raise money for war veterans. The symbol is still considered a positive aspect of Finnish culture, and the ring was worn by several actors and comedians to raise awareness of the charity drive. For those unaware of the history of the symbol in Finland, it can lead to trouble. A Moscow toy store was raided by police for selling scale models of historical Finnish aircraft, which investigators believed to be decorated with forbidden Nazi symbols.

4 Emblem Of Fohat

Theosophists see significance in the frequent presence of the swastika symbol in many different cultures and time periods throughout history. Madame Helena Blavatsky believed the swastika was the emblem of Fohat, or cosmic electricity, which is defined in Blavatsky’s Theosophical Glossary as follows: “the active (male) potency of the Shakti (female reproductive power) in nature. The essence of cosmic electricity. An occult Tibetan term for Daiviprakriti, primordial light: and in the universe of manifestation the ever-present electrical energy and ceaseless destructive and formative power. Esoterically, it is the same, Fohat being the universal propelling Vital Force, at once the propeller and the resultant.” According to Blavatsky in her book The Secret Doctrine, there was once an ancient time when the swastika was placed on the breast of defunct mystics and burned into the flesh of young initiates into the occult mysteries because “since Fohat crossed the Circle like two lines of flame (horizontally and vertically), the hosts of the Blessed Ones have never failed to send their representatives upon the planets they are made to watch over from the beginning.” She also claimed the swastika points in all directions and represents the sacred Four Elements, while its crooked arms are related to the Pythagorean and Hermetic scales. Anyone who understands the mysteries of the swastika “can trace on it, with mathematical precision, the evolution of Kosmos and the whole Period of Sandhya.” Modern theosophists spell it out more clearly. The seal of the Theosophical Society incorporates a clockwise swastika called a “whirling cross.” Its orientation suggests the dynamic forces of creation, representing the great process of becoming. The Society believes that a counterclockwise swastika, like that used by the Nazis, is representative of constructive or destructive forces bringing about the end of the world. The whirling cross is enclosed in a circle, representing the boundary of the universe, while its center represents a universal still point of calm. It is arranged on the Theosophical Society seal beneath the Hindu symbol Om, representing the unchanging absolute and eternal from which our world emanates.

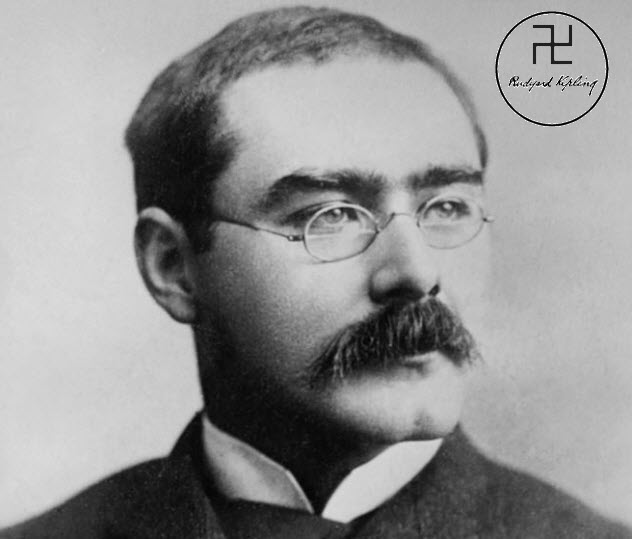

3 Kipling’s Literary Stamp

Many early works of British author Rudyard Kipling were adorned with the swastika symbol. He first began using the symbol on the dust jackets of his books in the late 19th century, most likely after he became familiar with it because of his father’s passion for Indian artworks. Both the clockwise and counterclockwise versions of the symbol appeared on his works because neither Kipling nor his publishers appeared to know which one meant good luck. Alongside the swastika, he frequently used elephant head imagery, an homage to the Hindu god Ganesha, as well as the lotus. Kipling himself despised the Nazis. According to David Gilmour in his book The Long Recessional, “In 1933 Hitler became Chancellor and quickly established his dictatorship. ‘The Hitlerites are out for blood‘, noted Kipling: ‘the Hun [was] stripped naked for war’ while the British, still running down their defences, were displaying less forethought than ‘incubated chickens’. [. . .] Kipling was so disgusted by the Nazis and the sight of their flag that he removed the swastika, a Hindu symbol of good luck, from his bookbindings. It had been his trademark for nearly forty years but it was now ‘defiled beyond redemption.’ ” To this day, however, there are reports of secondhand bookstores forced to field questions from confused or angry patrons about why their copy of The Jungle Book is emblazoned with National Socialist Party symbolism.

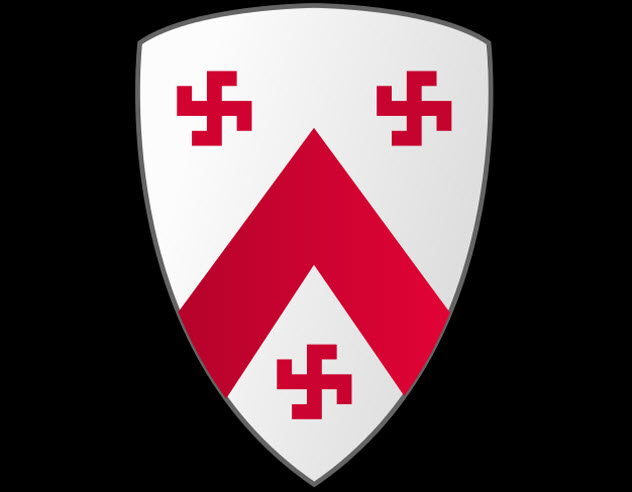

2 Fylfot

An older English name for the swastika symbol was “fylfot,” and it appeared in cultures throughout Europe. The word is said to be derived from the Anglo-Saxon “feower fot,” meaning “four-foot.” It is linked by some to a symbol of the hammer of Thor, which may explain its presence on church bells in areas of England like Yorkshire and Lincolnshire that had a heavy Norse influence. It is sometimes called the “hammer mark of Thor” or the “cross of Thor.” A variant would appear on Scotch Irish Presbyterian gravestones in the New World in the 18th century as a symbol for resurrection and eternal life. The symbol has been reclaimed by modern neo-pagan Odinists, who believe it was a holy symbol to pagan Europeans before Christianity. Various interpretations of its meaning have been suggested. For some, it is simply Thor’s hammer. For others, it represents a symbol of the cosmos revolving around the universal axis, Yggdrasil. Others say it is a variant of a sun wheel, as the unchanging revolutions of the Sun represent the order and regularity in the universe. The possible meanings of the four arms of the swastika include the high festivals (winter solstice, spring equinox, summer solstice, and autumnal equinox), the seasons (winter, spring, summer, and autumn), the phases of life (birth, life, death, and rebirth), the phases of the day (night, morning, day, and evening), the elements (air, fire, water, and earth), the phases of the Moon (lunar eclipse, waxing, full, and waning), and the cardinal points (north, east, south, and west).

1 Raelian Pro-Swastika Movement

Kooky UFO cult founder Rael represented his movement with a contentious symbol combining the swastika with the Star of David, which he claims to have seen on the hull of an Elohim spaceship. The Star of David is said to represent infinity in space, while the swastika represents infinity in time. The overall symbol stands for the relationship between time and space, eternity and infinity. All Raelians wear a medallion with this symbol. The fascist connotations, combined with an apparent support for social Darwinism and eugenics, led to negative attention to the cult on the part of the French police and government. In 1990, the earlier symbol was replaced with a six-pointed star around an abstract swirling galaxy, apparently in the hopes of coaxing Israel to allow the Raelians to build a $7 million embassy to the Elohim in Jerusalem. The Israeli government was not convinced and continued to rebuff the cult. In 2005, Rael reinstated the original version of the symbol. As quoted in the book, A Brief Guide to Secret Religions, Rael explains his logic as follows: “[our] courteous gesture didn’t help educate people so that they know this symbol is the symbol of the Scientists who created us, symbol that has been given to every one of their Messengers, which explains why we find it on every continent, usually associated with spiritual and peaceful groups. The swastika has been a symbol of peace for millions of Hindus and Buddhists and for the Raelians as well as it is their symbol of infinity in time, their symbol of eternity.” Since then, the Raelians have been pushing a movement to rehabilitate the swastika, launching an offshoot group called the ProSwastika Alliance. For several years, they have been holding an annual Swastika Rehabilitation Week in cities around the world. In 2014 and 2015, to the shock and confusion of local residents, they attracted controversy for flying over beaches and neighborhoods in New York with a plane bearing a swastika banner. They even broadcast a commercial on a large screen at Times Square, where a group of people in a swimming pool formed a swastika. Similar promotional events took place in Mexico, France, and South Korea. David Tormsen is slightly disappointed the sickle and hammer weren’t used as symbols for a Han dynasty agrarian movement or some obscure sect of industrious 19th-century Unitarians. Email him at [email protected]