10“Lord” Timothy Dexter

Sometimes it is better to be lucky than smart, and nobody exemplified this better than 18th century Massachusetts businessman Timothy Dexter. Born into a family of laborers, Dexter was largely uneducated but had a lifelong desire to integrate himself into the upper echelons of society. He took the first step in the right direction when he married a well-off widow while working as a leather craftsman apprentice. Dexter’s true stroke of fortune came towards the end of the Revolutionary War. By that time, Continental currency had depreciated so badly that $40 in paper money bought $1 in goods, hence the expression “not worth a Continental.” As a sign of good faith, wealthy Americans began buying Continental dollars from destitute soldiers. Wanting to fit in, Dexter spent his entire wealth on Continental currency. Afterward, Alexander Hamilton enacted his financial plan, and Dexter traded his Continentals for treasury bonds and made a fortune. Apocryphal stories soon arose of Dexter undertaking foolish financial ventures, yet, somehow, still making a profit. He was allegedly convinced to export wool mittens to the tropical Indies where they were bought by merchants headed for Siberia. Another time, people told Dexter to ship coal to Newcastle which he did, supposedly, during a miners’ strike and sold his cargo for a premium. Yearning to show off his intellectual side, Lord Dexter, as he called himself, wrote a 9,000-word half-biography, half-philosophy book. It had no punctuation, random capitalizations, and numerous spelling errors. Not surprisingly, the title made little sense: A Pickle for the Knowing Ones or Plain Truth in a Homespun Dress.

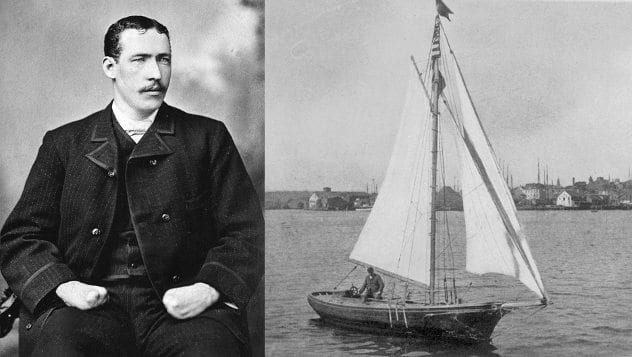

9Howard Blackburn

Howard Blackburn came from humble beginnings as a fisherman trying to make a living, first in Nova Scotia, then in Massachusetts. A 24-year-old Blackburn became a local legend in 1883 when a winter storm blew his schooner off course. The captain had to row back in freezing temperatures without the benefit of heavy mittens. Knowing what would happen, Blackburn maintained his hands in the curved position so he would be able to continue to row, even when they froze. He returned after sailing for five days without food, water, or sleep. His fishing mate died, and Blackburn lost all his fingers and a toe. Blackburn’s fishing career was over, but his heroic, new reputation helped him open a tavern which still stands today. Soon enough, though, the call for adventure beckoned again, in 1899, Blackburn returned to the sea. He performed a solo crossing of the Atlantic (his first of two) aboard the Great Western in 62 days. While this had been accomplished a few times before, it was done by people who still had the use of their fingers. Even a year before dying, a 72-year-old Blackburn was planning another transatlantic voyage.

8Henry Every

Henry Every might not be among the most famous pirates in the world, but his exploits were enough to rival those of any real contemporary or Hollywood creation. He was not known as the “King of Pirates” for nothing—in 1695, Every made off with one of the biggest plunders in buccaneering history. Every heard of a Mughal Empire fleet returning home to India with a vast treasure of gold and silver, defended by scores of cannons and riflemen. To even stand a chance, Every had to ally himself with other pirates and ambush the 25-ship Mughal flotilla. Every’s partner, Captain Thomas Tew, fell in battle against an escort ship. However, this allowed Every’s ship the Fancy to catch up to the Mughal flagship Ganj-i-Sawai. After a fierce fight and more than a few strokes of good luck, Henry Every took the Ganj-i-Sawai and plundered up to £600,000 in valuables, instantly becoming the richest pirate in the world. The attack significantly soured Anglo-Indian relations and, with a huge bounty on his head, Henry Every became the most wanted man in the world. Astoundingly, this did not stop him from leaving the pirate life behind and enjoying his spoils. Unlike most of his fellow pirates, Every was never captured or killed in battle. He simply disappeared from the history books, and nobody knows what happened to him or his treasure.

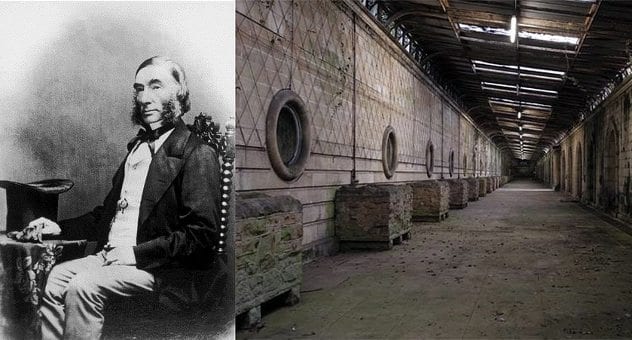

7William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck5th Duke of Portland

Like his father and his father before him, William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck became Duke of Portland and served as a Member of Parliament while residing at the family estate, Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire. However, he became better known for his eccentricities and for a bizarre paternity suit occurring almost two decades after his death. There is no doubt that Lord Cavendish valued his privacy. Many stories paint him as an extreme introvert. Allegedly, his valet was the only person allowed to see him. The duke communicated with everyone else either through him or in writing. All of the servants and workers on his estate were instructed to never acknowledge him and ignore him even if they had to pass by him in the hallway. The duke’s introversion led him underground, and he oversaw the extensive building of halls and tunnels underneath Welbeck Abbey. This included a secluded passage for his carriage all the way to the station, and a giant ballroom, even though Cavendish never invited anyone over, let alone throw a party. Eighteen years after his death, a widow named Anna Maria Druce came forward, claiming that Cavendish’s reclusiveness allowed him to lead a double life as her father-in-law, Thomas Charles Druce, before faking his death. The case dragged on for over a decade, leading to an exhumation, several counts of perjury, and two people being committed to an asylum.

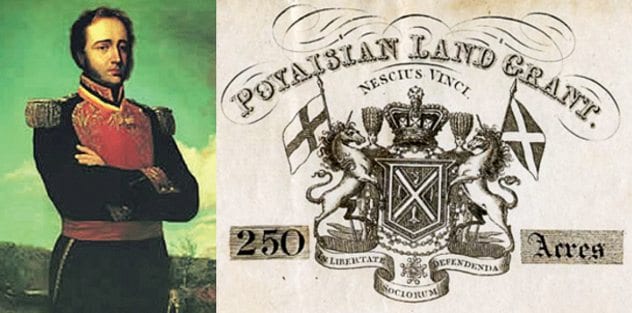

6General Gregor MacGregor

There are two vastly different chapters in the life of Gregor MacGregor, a member of the clan made famous by Rob Roy MacGregor. The first was his military career. MacGregor served as an officer in the British Army between 1803 and 1810, fighting in the Napoleonic Wars and rising to the rank of general. Afterward, he joined Venezuelan forces in their war for independence against Spain, becoming a hero worthy of full military honors upon his death. Then there is also the Gregor MacGregor who tried to pull off one of the most audacious cons in history. Upon his return to Britain, MacGregor claimed to have been made Cazique (prince) of a new country called Poyais near the Black River. This eight-million-acre area was rich and fertile but needed investors and settlers to develop it. Due to the disintegration of the Spanish Empire, investing in new Latin American governments was considered the smart thing to do, and MacGregor generously offered a £200,000 Poyais bond at a six percent return rate. Overall, MacGregor made £1.3 million off Poyais bonds, but there was just one problem—Poyais did not exist. Many of the Scottish settlers died in their new “home,” and when word reached London, MacGregor fled to Paris where he tried the con again and was arrested.

5Sidney Weinberg

Hollywood loves a rags-to-riches story and few, if any, top that of early 20th-century investment banker Sidney Weinberg. He came from meager beginnings—one of eleven children of Jewish immigrants who came to New York chasing the American dream. He dropped out of school at 15 and started looking for work. In 1907, sixteen-year-old Weinberg wanted to work on Wall Street. He picked a nice looking, tall building—43 Exchange Place—and went into every office asking if they needed a boy for errands. He landed a position as a janitor’s assistant at a small brokerage house named Goldman Sachs. One day, Weinberg delivered a flagpole to the Sachs residence where he made enough of a positive impression on Paul Sachs to get promoted to the mailroom. His hard work continued, and Weinberg went to business school on the company’s dime. By 1927, Weinberg became a partner. By 1930, he became CEO of Goldman Sachs after saving the fledgling company from bankruptcy. He kept this position for 39 years, earning the moniker “Mr. Wall Street.”

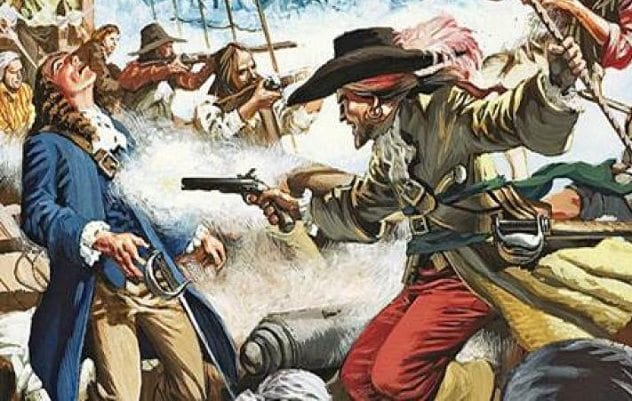

4“Red Legs” Greaves

The story of “Red Legs” Greaves’ life reads like a fanciful tale out of a book. Greaves was born sometime in the mid-17th century to Scottish parents exiled to Barbados by Oliver Cromwell for participating in the Scottish Civil War. Sold into slavery, Greaves tried to escape by stowing away on a ship, unknowingly boarding a pirate ship commanded by one Captain Hawkins. When he was discovered, Greaves had little choice but to join the crew, even though he despised Hawkins’ cruel treatment of his prisoners. Eventually, Greaves challenged Hawkins’ leadership and, after besting him in a duel, became the new captain. Greaves was a merciful, lenient captain and after a few successful scores tried to retire as a plantation farmer. Eventually, though, his past caught up with him, and “Red Legs” was arrested for piracy and sent to Port Royal to be executed. This was in 1692, the year of a massive earthquake that plunged two-thirds of Port Royal into the water and killed around 5,000 people. Greaves was one of the lucky survivors and escaped by joining the crew of a whaling ship. He would later become a pirate hunter and did such a good job that he earned a royal pardon. This allowed Greaves to live happily ever after and retire on his plantation home in Nevis.

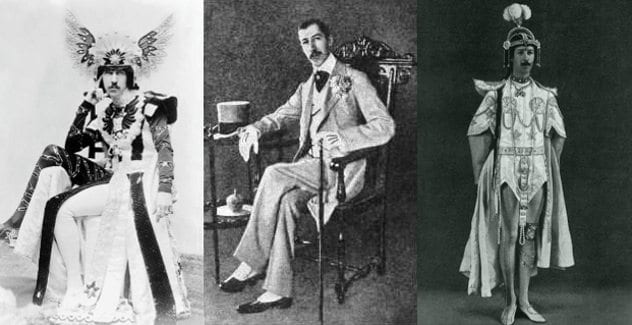

3Henry Cyril Paget5th Marquess of Anglesey

Henry Cyril Paget, Earl of Uxbridge and 5th Marquess of Anglesey, lived a life that would make any 1970s glam rocker jealous. At age 23, Paget inherited a title, a giant estate called Plas Newydd, and a fortune. By age 27, it was all gone. In 1905, aged 29, Paget died with millions of pounds in debt. The marquess embodied the “live fast, die young” mantra, although he preferred to spend his money on jewelry and luxury clothing. A typical outfit of the marquess consisted of a lavish dressing gown (he favored French tailor Charvet), accessorized with numerous jewels, and some sort of headdress or tiara. Most of these items were only worn once. When debtors sold his collection at auction, they found over a hundred bath gowns alone. A fan of the performing arts, Paget turned his home chapel into a theater. He hired one of the best acting troupes in the country to stage productions where he could play the leading role. The highlight of each performance was Paget’s sensual, snake-like dance which earned him the moniker “the Dancing Marquess.” Unsurprisingly, Paget’s flamboyant lifestyle sparked rumors that he was gay, but this was dismissed by his ex-wife of six weeks. According to her, the only person Henry could ever love was himself.

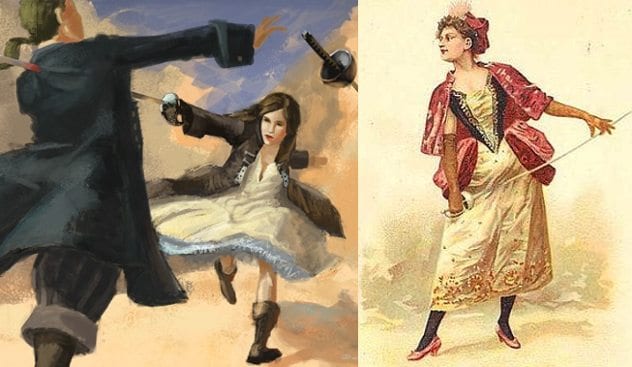

2Julie d’AubignyMademoiselle de Maupin

Few artists led a more thrilling life than 17th-century opera singer Julie d’Aubigny, known as Mademoiselle de Maupin. Her youth was marked by a string of duels and love affairs as the young swashbuckler roamed the French countryside looking for adventure. It all started in 1687 when 14-year-old Maupin fled Paris with a fencing master named Sérannes, staging singing and dueling exhibitions to earn a living. When she got bored of him, Maupin started a love affair with a young woman who was promptly sent off to a convent by her parents. Supposedly, Maupin followed her and gained entry into the convent as a postulant. There, Maupin faked the death of her lover by setting her room on fire and leaving behind the body of a recently-deceased nun. This prolonged their romance for a few more months before Maupin got bored and moved on again. Eventually, Maupin settled back in Paris where she became an acclaimed opera singer. However, this did not deter her from her wild ways. At a party at the royal palace, Maupin attended wearing men’s clothes, as she often did, and tried to strike a dalliance with a young woman. Three suitors, offended by her actions, challenged her to a duel. Maupin accepted and bested all three, although she later had to flee the city as duels were banned in Paris.

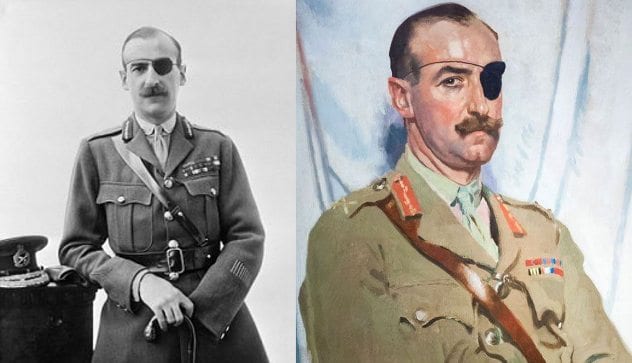

1Adrian Carton de Wiart

Adrian Carton de Wiart started his military career in 1899 by dropping out of college and joining the British Army to fight in the Second Boer War. He was sent back to England after being shot in the stomach and groin. At the outbreak of World War I, Carton de Wiart joined the Somaliland Camel Corps. During an attack, he was shot in the face, losing an eye and a bit of ear. Again, he was sent back to England to recuperate where Carton de Wiart acquired the black eye-patch which became his distinguishing feature. He went back to the war on the European front. At the Second Battle of Ypres, Carton de Wiart’s left hand was mangled by artillery. His hand was amputated back in England, and, after a quick break, Carton de Wiart was back on the frontline. This time he led the 8th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, at the Battle of the Somme and was awarded the Victoria Cross for commanding the entire battalion after all other commanders died in battle. Between wars, he spent time in Poland where he survived a plane crash. When WWII came around, Carton de Wiart gladly went into active duty again despite being in his 60s. He survived another plane crash over Libya in 1941 and spent the next two years as an Italian POW. In his autobiography, Carton de Wiart quipped, “Frankly, I enjoyed the war.”