SEE ALSO: 10 Stunning Photos Snapped At Just The Right Moment

10Dr. Bahnson’s Lily Pads

Dr. George Frederic Bahnson was a man of many talents. He was one of the most acclaimed medical diagnosticians in his time, he served as a Union sharpshooter in the Civil War, and he grew the biggest lily pads the US had ever seen.

9The Antarctic Snow Cruiser

By the 1940s, Antarctic exploration mania was reaching a fever pitch. Fueled by the exploits of Shackleton, Falcon, and Charcot, the world watched with breath held and fingers tensed as each new team forged a path through the frozen southern wastes. In an effort to keep up with the spirit of discovery, new and better technologies were rolling off the assembly lines to help these heroic men better cope with the elements. One of these innovations was the Antarctic Snow Cruiser. Designed by Dr. Thomas C. Poulter, an Antarctic veteran with the lung damage to prove it, the Cruiser was supposed to be the epitome of exploration technology. It had specially designed treadless tires that were supposed to be able to bridge the wide crevasses that had prevented past explorers from using vehicles. After months of development, the Cruiser touched Antarctic ice for the first time on January 15, 1940, at the Bay of Whales. For a brief and glorious moment, it perched on the permafrost like a fierce metal penguin, and then the massive tires broke through the snow and spun out. The crew dug it out, only to have the engines overheat a few hundred meters farther in. Thus began the most frustrating months humans have ever experienced in Antarctica. Eventually, the expedition decided to simply cover the Snow Cruiser with timber and use it as a glorified tent. It was abandoned when the team left Antarctica early the next year.

8American Lobsters

The general consensus on lobsters is that they’re almost too big to fit on a dinner plate but not quite. At an intellectual level, we realize that they get a lot bigger than the ones at the grocery store, but this photo hammers that understanding home with visceral enthusiasm. Although these aren’t the largest lobsters on record—that distinction goes to a beast caught off Novia Scotia that weighed in at 20 kilograms (44 lb)—each of their claws is bigger than the boy’s torso, giving yet another argument for staying out of New Jersey’s water. The American Northeast is no stranger to clawed beasts of the deep. The growth of the American lobster industry paralleled the advent of canning technology in North America, and by the middle of the 19th century, demand for lobsters was skyrocketing. Supply quickly rose to meet that demand to the point. The northeast got so inundated with lobster meat that it came to be considered a “poor man’s food.” That’s obviously changed by now, although lobster fisheries the world over still pull in over 200,000 tons of this particular decapodian delicacy every year.

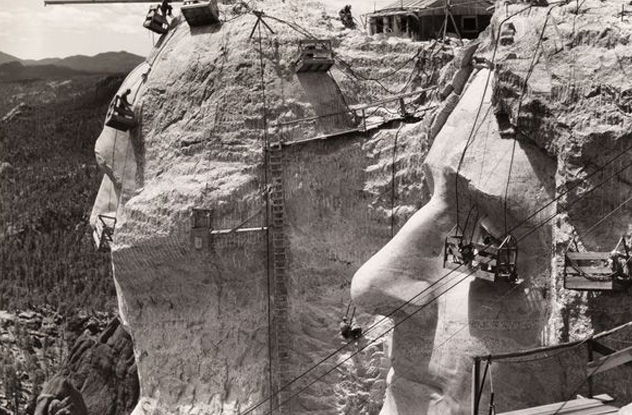

7The Carving Of Rushmore

This photo from the construction of Mount Rushmore was taken in the late ’30s, just a few years before the monument’s completion in 1941. The project was absolutely immense in scope, especially considering that it was built on the heels of the Great Depression. Like ants on an action figure, workers spent 14 years clinging to the nostrils and eyebrows of America’s greatest presidents. Using steel cables and massive winches housed in buildings at the top of the mountain, 30 men at any given time first blasted then carved the monument out of Rushmore’s granite face. Dynamite charges carved out the features to within 8 centimeters (3 in), after which workers hand-carved the rest with what became known as the honeycomb method. Using jackhammers, workers bored a series of closely spaced holes, which were then knocked away with a chisel. The only person who died during the construction of Mount Rushmore was its architect, Gutzon Borglum, who died of natural causes six months before it was finished.

6Wreckage Of A Zeppelin

Thanks in part to the Hindenburg, the early, hydrogen-filled Zeppelins are now synonymous with flaming tragedy. In World War I, 84 Zeppelins were built for the German wartime effort. Sixty of them were destroyed, and about half of those losses weren’t even from enemy fire—they were just accidents. In the aftermath of the various bombing raids that never seemed to do much damage, European countrysides became impromptu grave sites for the burned-out carcasses of these massive airborne leviathans. The photo above was taken in Mison, France in 1918. Our closest modern equivalent to these large-scale wreckages would probably be underwater shipwrecks, but even those rarely come close to the size of the largest airships of the era.

5The Redwood Loggers

The oldest living giant sequoia (giant redwood) on record was 3,500 years old. It was aged based on its trunk rings, so it had to die to get the record. The giant redwoods of California are an iconic image of Americana, nearly as much so as the fleets of trucks weighed down by redwood logs larger than the trucks themselves. A single truck could carry 16,500 meters (54,000 ft) of boards in raw lumber. Prior to the California gold rush of 1850, California’s redwood groves were pristine and untouched. Since then, over 95 percent of the old-growth forest has been cut for timber. The forests from which these trees came had been around for so long that they’d formed an evolutionary symbiosis with the wildfires that have historically swept through California. The redwood’s bark is highly fire-resistant, so it takes minimal damage while competing species are completely wiped out.

4The Mark Twain

Even an image of 3-meter-wide (10 ft) redwood logs stacked on a truck doesn’t drive in the sheer size of these massive trees like this photo taken at ground zero of the felling of the “Mark Twain” redwood in 1891. This was an example of a trophy tree, a tree cut down as an expression of settlers’ conquest over the primeval landscape of the American West. A lot of those photos made their way into era postcards, usually with men with axes assuming casual “no-big-deal” poses. Since giant sequoias were prone to shattering when they fell, the loggers who took down Mark Twain spent eight days digging a trench that they lined with feathers to keep the tree intact when it crashed to the ground. Two cross-sections from the base were sliced out to go to museums, and the rest was broken up for fence posts.

3Iraq’s Roman Arch

This stone arch in modern-day Iraq is certainly large—impressive, maybe, but not necessarily breathtaking. What’s incredible about it, though, is how something so large and seemingly frail could still be standing after nearly 1,500 years. Identified only as a Roman bridge over the Wadi Al-Murr by its photographer, archaeologist Max von Oppenheim, it was likely built during the reign of Roman emperor Justinian I. The Wadi Al-Murr is a waterway running through the Ninawa Province of northern Iraq, just under the border of modern-day Turkey. In the sixth century, Justinian built a series of bridges and dams in that region to prevent flooding in the Mesopotamian city of Dara. While most of those structures were decidedly more impressive, this lone arch is one of the few remaining complete structures from the Roman occupation of Iraq. And as of 2006, it was still standing.

2The Alaska State Fair

Cabbages wider than a wheelbarrow, pumpkins so heavy they collapse under their own weight—there’s something softly arrogant about giant vegetables, as if they’re using space that shouldn’t be theirs. In the Matanuska-Susitna Valley, neck-deep in the Land of the Midnight Sun, giant vegetables are a heritage, one fiercely protected by its resident farmers. The Alaska State Fair is where the goings-on get festive, and it’s there that you’ll find the 210-centimeter (89 in) gourds, the 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) pumpkins, and the largest cabbages in the world. Why do they get so big? A lot of it comes down to geography: Since that part of Alaska gets upward of 20 hours of sunlight per day in the summer, vegetables just sort of keep trucking, feeding on the endless dawn of the Alaskan soul.

1Building The Nagarjuna Sagar Dam

In a world packed with machinery and automation, the impact of sheer manpower is often overlooked in favor of a more technological approach. It’s hard to believe, but the seemingly chaotic wooden scaffolding and hive-like workforce in the photo above was just a piece of the carefully planned construction of the largest masonry dam in the world. Located on the Krishna River in India, the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam spans 1.6 kilometers (1 mi), stands 150 meters (490 ft) tall, and the reservoir it creates is one of the world’s largest man-made lakes—and all of it was built with human labor. The dam is considered the first of India’s “modern temples,” structures meant to reduce India’s dependency on foreign imports, and plenty of people can be proud of that: In its 12 years of construction, there were never fewer than 50,000 people working on it at any given time.