10 Catterina Vizzani

Catterina Vizzani was born in Rome in 1719, and hers is the first story we have of a woman examined by a doctor in search of a physical cause for her attraction to other women. By the time she was 14, she had fallen in love with the young woman who had been teaching her embroidery and took to dressing in men’s clothes in an attempt to woo her. It was a full two years into the relationship that the other girl’s father put an end to it, and Vizzani took the opportunity to move to Rome and adopt a completely male persona. Calling herself Giovanni Bordoni, she began working for a vicar who was incredibly upset by his new employee’s woman-chasing habits. After several years, she moved on to another town and fell in love again. This time, she attempted to run away with her willing suitor. When the girl’s uncle gave chase, Vizzani was shot in the leg. The wound, at first thought only minor, turned fatal. It was only when she died that she recounted her story to an attending nun, requesting that she be buried in women’s clothing and as a virgin. After her death, the testimony of the attending physician was recorded. He noted that she had already been examined—and cut open—to confirm that she wasn’t pregnant at the time of her death. His complete examination of her determined that she had ultimately died from gangrene in the gunshot wound, and that aside from that, she was perfectly normal and exactly like any other woman. The physician went on to say that whatever had happened to her to cause her to dislike the company of men wasn’t something physical, and he speculates that it may have been a early trauma that caused her to prefer women. Her father, on the other hand, simply said that it was the way she had been born.

9 John Rykener

John Rykener’s story is an intriguing one, as much because of the information that we don’t have as because of the information we do. The only documentation in existence is a partial transcript of a court case, dated December 11, 1395. According to the accusations, John Rykener had been apprehended by authorities after being caught hanging out in Soper’s Lane plying his trade as a prostitute. He had been calling himself Eleanor and was dressed in women’s clothing when he was approached by John Britby. Britby, thinking he really was a woman, hired him for what prostitutes are hired to do. Both caught and taken to prison, Rykener later testified that he had learned from a female acquaintance how to act, dress, and perform as a woman. According to him, he lived part of his life as a man and part as a woman, depending on what the circumstances dictated. When he needed to make a living at embroidery, he said, he dressed as a woman. That’s all we know about him. The court testimony was a part of the records of the City of London, which were transcribed and compiled by Cambridge University in the 1920s. While most of the cases were transcribed pretty thoroughly, there was only one (aside from mundane affairs like the creation of wills) where a long testimony was shortened to a sentence. According to the Cambridge version, John Rykener was only involved in a case “of two men charged with immorality,” and it was only when they looked back at the original version that they found what really happened, suggesting that there was an active desire to just not even talk about such things in the decades around the assembly of the reference books.

8 Catharina Margaretha Linck & Catharina Margaretha Muhlhahn

In October 1721, two women were put on trial in Halberstadt, Germany for “serious crimes,” including their marriage. They were accused of sodomy, and while the laws on sodomy were quite clear, what wasn’t clear was whether or not it applied to women. Catharina Linck, an illegitimate child raised in an orphanage until she was a teenager, took to dressing in men’s clothing to secure her virginity. Eventually joining a religious group called the Inspirants, she went on to become one of the group’s most famous prophets. For two years, she traveled with them and performed duties from giving the Eucharist to interpreting the words and actions of the spirits and visions that appeared to her. Her time with the group was limited, though, as her gift of prophecy started to fail her, most notably when she told a man he could walk on water. He couldn’t. Linck made attempts at joining the military. Her first ended when she revealed she was a woman to keep from being hanged for desertion, and the second was ended when her revelation followed her to her new unit. She eventually found work posing as a male cloth-maker. Here, she met and married Catharina Muhlhahn. According to the court case, the marriage wasn’t a happy one. Muhlhahn complained that she was the recipient of frequent beatings, and whatever money she earned wasn’t hers to keep. She claimed that she had no idea that she had married someone who was actually a woman, as Linck had hidden her true gender behind lies and threats. The whole case was hugely debated in the courts. It was difficult to determine just how much of a willing partner Muhlhahn was in actions that were a capital crime. Even once the courts determined that she didn’t know her husband was a woman, they still had to deal with the idea that she had been party to the marriage and everything else that had gone on between them. Add in the idea that the defendant was a female accused of sodomy, and things became a little hazy. Ultimately, it was ruled that women were also capable of committing sodomy and should be punished as such. Linck was sentenced to death by the sword, and Muhlhahn received a somewhat lighter sentence as an unwilling and unknowing partner. Her fate was three years imprisonment followed by banishment.

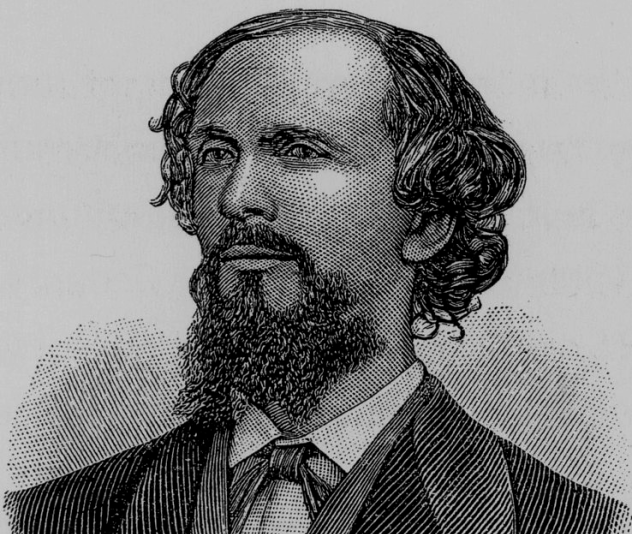

7 Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs

Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs was born in Germany in 1825. He was a lawyer, he was gay, and he made a pretty incredible stand for gay rights. Ulrichs is credited as one of the men who turned the tide from persecution and capital punishment toward tolerance. In 1867, he appealed to the Sixth Congress of German Jurists, standing before more than 500 of his colleagues and contemporaries in a time when being gay was something unnatural that needed to be curbed and punished. Ulrichs spoke freely about how those that gravitated toward a same-sex lifestyle didn’t have anything wrong with them, that there was nothing unnatural about their feelings or their beliefs, and that the persecution against them needed to stop. He didn’t get through his speech; he was only partway through when the noise from the crowd started to drown out his words. But it was the start of change, and a handful of his colleagues took his side. One even contacted him later, to confess that he, too, was gay, and to thank him for giving him the courage he needed to admit that. Ulrichs went on to write about how persecution needed to stop, and he also suggested the use of a term that was less volatile than the ones that had been used up until that point. He suggested “Uranian” in place of terms like “sodomite,” saying that changing the terminology would help people stop associating the acts with something criminal. Tragically, the law he spoke out against went into effect, and it was the same law that would later be used by the Nazis to support their stance on and persecution of anyone who was gay. Ulrichs ultimately moved to Italy in a self-imposed exile, but his words are still powerful: “Many have been driven to suicide because all their happiness in life was tainted,” he wrote. “Indeed, I am proud that I found the courage to deal the initial blow to the hydra of public contempt.”

6 Mary Hamilton

The case of Mary Hamilton is another in which we have only the barest of details. In 1746, an article was published in a newspaper from Bath, England about the strange case of Mary Hamilton. According to the paper, Mary Hamilton had taken the identity of first George Hamilton and then Charles Hamilton and had married another woman named Mary Price. The details of the case are sketchy, as the newspaper article says that those details aren’t fit to be published. It was ultimately decided, though, that Hamilton was essentially guilty of fraud, and sentenced to six months imprisonment and to be publicly whipped in four different towns. The whole incident was said to have been particularly difficult for the courts to rule on, simply because there wasn’t a precedent or any laws in place dealing with a relationship of the sort between women. It did, however, inspire the author Henry Fielding to write The Female Husband, or the Surprising History of Mrs. Mary, alias Mr. George Hamilton. The story fills in the blanks with what Fielding supposed happened in the case. He paints the picture of a young woman (Price) who falls in love, only to be left when her beloved marries a man. The heroine flees to Dublin, where her affections are once again rebuffed. Finally, she befriends (and marries) an older widow, living with the woman in the guise of a man. Her true identity is discovered several times, until she is approached with an offer of marriage from a doctor (Hamilton). While the match is initially much more socially acceptable, the doctor’s true identity is eventually discovered—along with, presumably, the reason for Price’s happiness. It’s not the first time a lesbian encounter was dealt with in fiction, but it was one of the first works in English that portrayed a protagonist as a sympathetic character that the readers could relate to.

5 Frederick Gotthold Enslin & John Anderson

The idea of LGBT in the military has long been a hot button topic of discussion, protests, and legislation, and it has kind of a strange history in the United States. Records from the American Revolution show that while there were numerous court martials handed down, there were only two given out on the charge of sodomy, as American sodomy laws were rarely enforced until the 1880s. It’s suspected that there was much more to the two enforced cases than we know. On March 10, 1778, Frederick Gotthold Enslin was sentenced to be literally serenaded on his walk of shame out of the camp and out of the military, to a tune played by the drummers and fifers. There aren’t many records that still survive, but among those that do are George Washington’s notes on the subject. It seems that the accusation wasn’t the only charge, though, and only about a week before he was put on trial, Ensign Anthony Maxwell was put on trial for spreading scandalous rumors about Enslin in an attempt to damage his reputation and his character. Also included in the charges against Enslin was perjury. It’s suggested that Enslin’s crime wasn’t being gay; it was sexual assault and then lying to cover it up when the man whom he assaulted brought charges. The handwritten notes from Washington’s secretary show quite clearly the man’s disgust with the whole thing in the rather dramatic handwriting it’s recorded in. Later, in 1792, there’s the mention of a John Anderson from Maryland, found guilty of attempting sodomy. His sentence was to “Run the Gauntlope” after the evening’s roll call—a much lighter sentence than Enslin’s removal from the military. It brings up some intriguing questions about the Revolutionary-era stance on LGBT tendencies in the military: Was it just not such a big deal at the time?

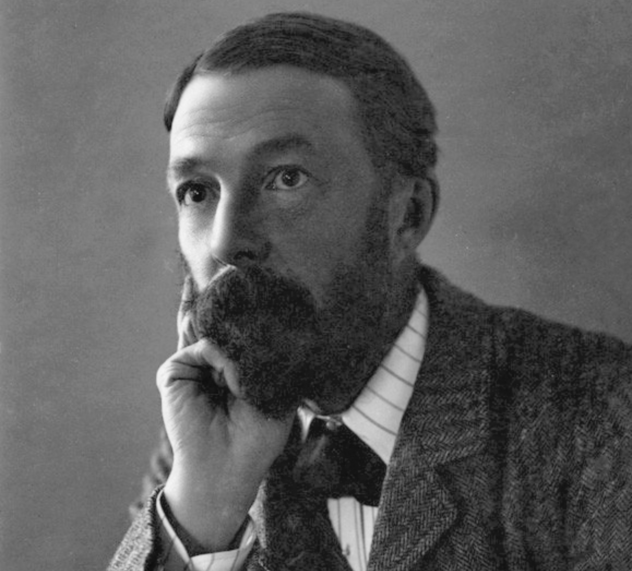

4 John Addington Symonds

Symonds is credited with being one of the earliest writers to link writers and artists of the past with the emerging ideas of homosexual culture and freedoms. He was also credited for being the first to translate many of Michaelangelo’s works and the first to bring the artist’s own homosexual leanings to the public eye. Born in 1840, Symonds was an incredibly learned man who, from childhood, was exposed to arts and literature from Greek sculpture to Renaissance arts; culture was a career for him. Letters written to his sister reveal some insight into a man tormented by his urges, in which he says, “I had hoped to make my work the means of saving my soul.” Constantly plagued by ill health from tuberculosis and chronic bronchitis, he called himself an old man by the time he was 40. His own battle with coming to terms with who he was had been clouded by the discovery of the involvement of the headmaster of his school with one of the students. It was Symonds that made the affair public, and for long after, it had only helped to throw his own feelings into doubt. His father’s attempts to be supportive were often well-meaning but ill-advised, and his own attempt at marriage, although he would have four daughters, would be an incredibly miserable endeavor. His memoirs are a frank look at his struggles while living with his family and surrounding himself with friends who knew his true feelings and lauded him for his generosity, his kindness, and his philanthropy in both Italy and Switzerland. Even as he was providing new translations to ancient works and bringing them—and their previously unpublicized erotic overtones—to the masses, he was traveling with his boyfriends while keeping his wife and children provided for and helping countless others get started in business.

3 Margaret Clap

In 18th-century London, so-called “molly houses” were the places to go for men to meet other men. By all accounts, there were a lot of them, and law enforcement had their hands full trying to make sure they were shut down and the men that were using them were treated according to the law, which could mean punishment up to hanging. Margaret Clap was the owner and tavern-keeper of a molly house that started in 1700 and was only finally raided in 1726. In those two and a half decades, hers had become one of the most popular molly houses around, with more to the place than a number of private rooms. There was a huge main room, a guaranteed supply of drinks to go around, and always music and dancing. There was no name given to the establishment, as it was technically private—those that entered needed to be a part of the club in order to protect the identity of her clients. In February 1726, acting on information gotten from informants that had made their way into the molly culture, police raided Clap’s home. No one was actually caught in the middle of doing anything, but 40 men were arrested anyway. Some were set free, some were ordered to pay fines, some were given a jail sentence, and, when the trials were done, three were hanged. Margaret herself is something of an enigmatic figure. According to what we know about her, she was in the business of running a molly house for the fun of it all and for the people. It wasn’t unheard of for her to defend men arrested as mollies in court, and there’s nothing to suggest that she actually was operating a brothel or tending male prostitutes as the charges against her suggested. When she was put on trial for her part in running a house of ill repute, her only defense was to say that as a woman and she didn’t concern herself with what went on behind the closed doors of her rooms. She was sentenced to a fine, to the pillory at Smithfield, and two years in jail. During her ordeal at the pillory, she was confronted with an angry mob, fainted several times, and removed after going into seizures. There is no further record of her.

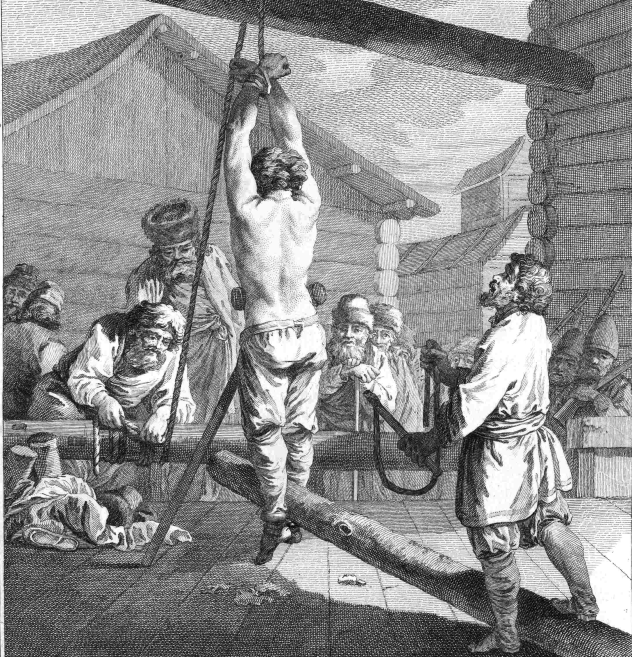

2 Felipa De Souza

When the Inquisition originally looked at dealing with the idea of same-sex relations, they targeted male relations. Women were, by nature, more sensitive and more in touch with each other’s feelings, and it was more natural for them to be closer in vicinity and in contact than men. But in 1591, Felipa de Souza was brought before the Inquisition in Brazil. They had gotten hold of what they deemed “lustful letters” that she had written to another woman, Paula de Siqueira. Since the Inquisitors didn’t see any way that there could be any real physical relationship or sexual act between two women, their actions were said to be nefarious acts, and de Souza was told to confess her sins. De Souza told it all. She had been in a relationship with the other woman for two years, and everything that she had said in the letters—all of the emotion feelings and all of the physical acts—were absolutely true, and she’d shared everything with her beloved. She was, of course, found guilty. Her sentence was to walk through the city, barefoot, while being whipped. She was forced to a bread-only fast, ordered to pay a fine, then exiled from the city and told to take all of her foul ways with her. Today, her bravery is still remembered by the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, in the form of the Felipa de Souza Award. The award is given to an individual who goes above and beyond to encourage the extension of all basic human rights to everyone, no matter what their sexual orientation is.

1 Thomas(ine) Hall

In 1628, a group of Virginia townsfolk were presented with a peculiar problem: They had no idea if their newly purchased servant was a man or a woman. When they purchased their servant, they did so thinking that they were getting a woman named Thomasine Hall. But some pretty creepy examinations while she slept left some questions. It seemed that “she” was really a “he.” Thomasine was born in Newcastle as a girl and raised as such in London. After losing her brother at a young age, it’s thought that by necessity she stepped into a more masculine identity, enlisting in the military as Thomas. After the period of military service was up, she was once again Thomasine, supporting herself by needleworking. Eventually, her adventurous spirit got the better of her once again; she took up her male identity and headed for Virginia. After being accused of theft in her male persona, she once again became Thomasine, and by then rumors were all over the town. After an accusation that Thomas had slept with a servant girl named Bess, the question of whether he was a man or woman wasn’t just a matter of gossip any more but a matter of honor. So the case went to court, and the verdict was a bizarre one. Thomas(ine) was found to be both a man and a woman, and as such, was ordered to wear men’s clothes with women’s accessories—namely a hat and an apron. It was, in the end, a very strange interpretation of the difference between sex and gender, an issue that we’re still dealing with today, albeit in a different but sometimes no less strange manner. Read More: Twitter