No one has ventured to the other side and returned. It means that these are actually guidebooks for the living, providing maps of our psyche and reminders of our mortality.

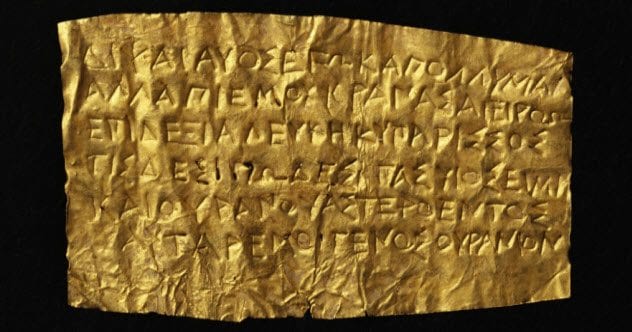

10 Orphic Gold Tablets

A mysterious golden tablet was found folded into the ashes of the deceased in a bronze urn unearthed in Thessaly. The ancient Greek inscription revealed that this was a totenpasse—a passport for the dead. Dating from 300 to 350 BC, the tablet contained specific instructions to quench the deceased’s incredible thirst. Some springs led to memory loss, while others provided nourishment. The tablet also provided a series of formulaic answers to satisfy the judges of the afterlife. Similar passports for the dead have been found throughout the ancient Greek world. They have long been labeled “Orphic” after the religion based around Orpheus, a musician who traveled to the underworld in search of his love. However, many experts now feel that they cannot all be lumped together but represent many mystery schools.

9 Bardo Thodol

The Tibetan Book of the Dead—or Bardo Thodol—is a guidebook to the afterlife and reincarnation. Dating to the eighth century, it was originally entitled The Great Liberating through Hearing in the Intermediate Stages. The work describes the process after death as the deceased journey to either reincarnation or buddhahood. Terrifying ghosts, demons, and spirits assail the dead. The goal is to not fear. Having lost their corporal form, the deceased have nothing to fear from the monsters. As the dead negotiate this labyrinth, they must make sure not to let their souls slip out through lower orifices. Carl Jung relished the work and considered the demons of the afterlife to be a window into our psyche. The work has been influential among the beat, hippie, and psychedelic movements. Death isn’t going anywhere. The book’s popularity remains assured.

8 Ars Moriendi

The Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) are two related texts from the mid-15th century. The Black Plague and warfare had decimated Europe. Death was everywhere, and people needed solace. An anonymous Dominican friar created the original “long version” in 1415. In 1450 came the “short version,” which is notable for its pairs of wood-block prints. The first showed the Devil tempting the deceased. The second offered a solution for that temptation. The prints contained powerful imagery that could be understood by everyone. This was one of the first books printed in movable type. With 100 editions before 1500, Ars moriendi was a hit. The major metaphor of Ars moriendi is that the afterlife is a maze of temptation.

7 The Book Of Arda Viraf

This holy text of Zoroastrianism is considered the “Iranian Divine Comedy.” The work follows Arda Viraf as he descends into the underworld. As legend goes, Arda Viraf consumed wine and henbane to enter a trance. His soul left his body and traveled to the other side. After seven days, his soul returned to his body. He wrote down his visions in what would become the Arda Viraf Namag—or The Book of Arda Viraf. The date of the work is unknown. It reached its completed form between the 9th and 10th centuries. The deceased arrive at Chinvat Bridge, where they receive judgment. If good deeds outweigh the bad, the deceased are led to paradise by a beautiful woman. If the scales tip toward wickedness, the bridge grows narrower until a vile hag plunges the deceased into Hell.

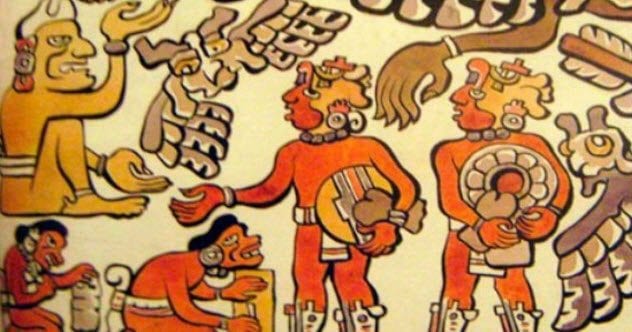

6 Popol Vuh

The Popol Vuh is considered the Mayan bible. It originated as a Mayan codex translated into Spanish in 1550. The Popol Vuh follows twin brothers Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who journey to the underworld. They trick the lords of death into allowing them to return. Their adventure provides a detailed map of Xibalba, the Mayan underworld. The goal of deceased Maya was to make it to paradise, but Xibalba was a treacherous place seething with terrifying man-eating deities, perpetual darkness, and festering rivers of blood and pus. The twins discovered that paradise lay across Xibalba, down nine layers to the middle world, and then down another 13 levels. A select group of Maya did not need to face these challenges: fallen warriors, women who died in childbirth, suicide victims, and losers of the deadly ball game pok-a-tok.

5 Amitabha Sutra

The Amitabha Sutra is one of the central texts of Pure Land Buddhism. This branch of Mahayana Buddhism is widely popular in East Asia, although it originally developed in the Indian subcontinent. This teaching reached China via the Silk Road. Sometimes, ideas were more valuable than the goods carried along this trade route. The Amitabha Sutra is concerned with the afterlife. It describes the Western Paradise—or Sukhavati—in great detail. It is common for members of the Pure Land sect to chant this sutra to the dying. It serves to soothe and provide practical information. The goal is to overcome our innate fear of the unknown and embrace death with peace.

4 Holy Dying

Published in 1651, Holy Dying is the second part of a two-book series that is considered the artistic high point of the literary movement that started with Ars moriendi. Its partner piece, Holy Living, instructed the faithful on how to lead a righteous life. Holy Dying prepared them for the afterlife. The author, Jeremy Taylor, is considered to be the “Shakespeare and Spenser of the pulpit.” The rich metaphors and poetic language in Holy Dying set it apart. Many considered this work to be a high point of Stuart-era literature. Jeremy Taylor was a cleric for the Church of England during the reign of Oliver Cromwell. Taylor even spent a brief period of time in prison for his royalist leanings. The work emerged as a ray of light in an age of death.

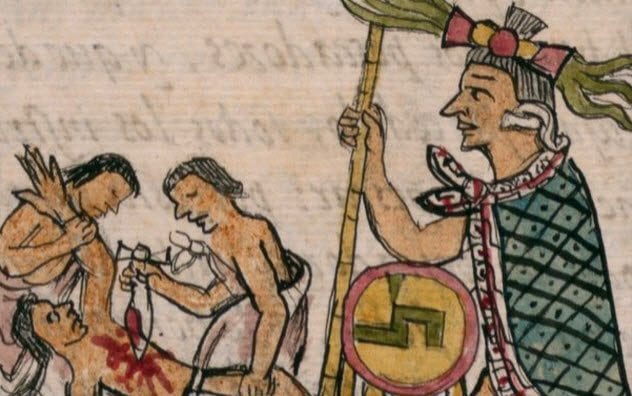

3 Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex was a 16th-century exploration of Aztec culture. The work took decades to complete and its creator, Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagun, has been labeled “the first anthropologist.” Sahagun was not working for the benefit of the Aztecs. His goal was to evangelize. Book Three of the Florentine Codex chronicles the journey following death. The Aztecs believed that a person’s position in death was based on their status in life and mode of death, not how they lived. Passing from old age and illness sent people to Mictlan, a dark underworld. Mictlan was inhospitable, filled with man-eating beasts, treacherous landscapes, and tempestuous weather. There was also Tlalocan, a paradise of eternal spring and abundance. This was reserved for victims of lightning, drowning, and select diseases. Beyond this lay an even richer paradise reserved for sacrificial victims and fallen warriors.

2 Heaven And Hell

Emanuel Swedenborg has been called the “Swedish da Vinci.” He pioneered scientific, philosophical, and religious advancements. Born in Sweden in 1681, his work on trance states and dream analysis predated Freud by more than a century. Swedenborg spent much of his time studying alternative dimensions accessed through altered states. The result of his explorations was a book called Heaven and Hell. This guidebook for the deceased discusses the angels, demons, and spirits that one will encounter on the other side. It also addresses theoretical questions, such as “are non-Christians in Heaven?” Swedenborg also lays out a formula for Heaven and one for the Hell-bound. Based on trance visions, Swedenborg’s findings are suspect. However, given that he predicted the exact time and date of his death, we might have something to learn from this intellectual giant.

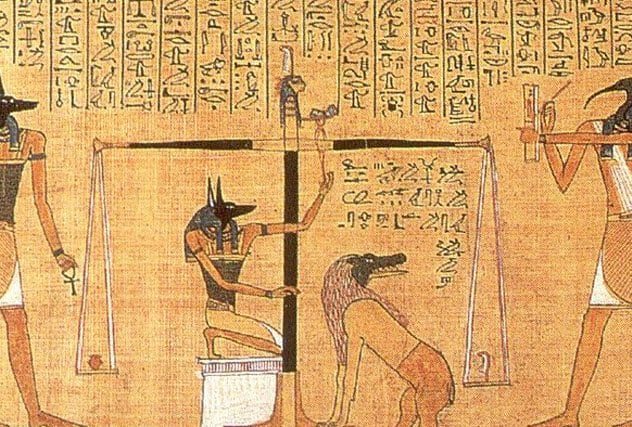

1 Book Of The Dead

For the ancient Egyptians, the Book of the Dead was a collection of spells intended to help the deceased navigate the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians believed that the other side was a perilous world filled with man-eating monsters and tests. This work even provides specific answers for the underworld’s gatekeepers. The Book of the Dead dates back to the New Kingdom—roughly 1500 BC to AD 100. Most of the spells trace back to the earlier Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts. The Pyramid Texts date from the Old Kingdom and were strictly for royal use. The later Coffin Texts were funerary spells engraved on Middle Kingdom coffins of royalty and commoners. The Book of the Dead is made of several hundred papyrus scrolls. The largest is the Greenfield papyrus. This 27-meter (90 ft) scroll was not shown in public until 2010. Many of the original papyri are so fragile that they would disintegrate within months of viewing. Abraham Rinquist is the Executive Director of the Winooski, VT, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.