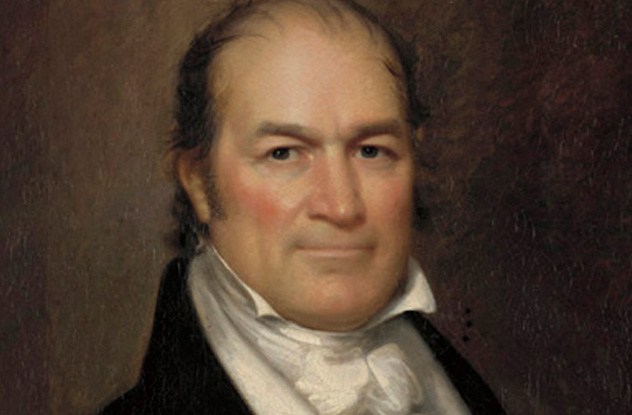

And then came James Monroe. There’s no denying Monroe was an important president. Under his administration, the US initiated the Monroe Doctrine, bought Florida from Spain, and passed the Missouri Compromise. Still, Monroe wasn’t exactly as interesting as his predecessors. Or was he? The last Founding Father to become president, Monroe was actually a pretty fascinating man. While he’s overshadowed by the Big Four, the man was an incredibly colorful character and, believe it or not, a real-life action hero.

10He Raided A Governor’s Mansion

If you were an American colonialist in the early 1770s, you were probably feeling a little anxious. Snowball fights were getting wildly out of hand, people were throwing some pretty crazy tea parties, and in 1775, somebody shot a really loud gun in Lexington, Massachusetts. It’s safe to say tensions were rising, and plenty of Americans were itching to get in on the action. One of those Americans was a 17-year-old college student named James Monroe. Long before Jon Stewart and Glenn Close walked its hallowed halls, James Monroe was studying at the College of William & Mary. At least he was trying to study. Truthfully, Monroe was probably more concerned about the upcoming revolution than whether his homework was finished on time, especially since Lord Dunmore was being such a royal jerk. The governor of Virginia, Dunmore was loyal to the crown and infuriated the colonialists by storming into Williamsburg, borrowing all their gunpowder, and forgetting to give it back. Like most of his fellow Virginians, Monroe was ticked off with this Tory, and in June 1775, the future president and his college buddies decided it was time to teach this governor a little lesson: You don’t mess around with a Southerner’s guns. Like any royal governor, Dunmore was something of a showoff. The foyer of his Williamsburg mansion was full of weapons, everything from muskets to swords, in an attempt to wow anyone who stepped inside his home. But with this revolutionary fervor sweeping the countryside, Dunmore started feeling a little antsy and skipped town. Monroe and his posse stormed the governor’s mansion and grabbed every single weapon in sight. By the time they were done ransacking the place, they’d made off with over 200 muskets, over 300 swords, and 18 pistols. Not a bad haul, not bad at all, and when Monroe donated all that firepower to the revolutionary cause, the local militia was pretty darn pleased.

9He Was A Revolutionary War Hero

Unfortunately for young Mr. Monroe, he never got a chance to collect his sheepskin. There were more important things going on, like sticking it to the British. After dropping out of college in 1776, Monroe joined up with the revolutionaries and quickly became an officer in the Continental Army. Before the war was over, the man climbed the ranks to lieutenant colonel and saw combat in places like Germantown and Monmouth. Monroe was also sort of a Revolutionary Forrest Gump, showing up at key places and interacting with major figures. He served as an aide to Lord Stirling, and after the Battle of Brandywine Creek, he actually took care of the Marquis de Lafayette after the Frenchman was wounded in battle. Monroe was with George Washington when the general crossed the Delaware, and he suffered through the devastating winter at Valley Forge. Perhaps most impressively, Monroe was shot in the shoulder at the Battle of Trenton (after crossing the Delaware, we’re backtracking a bit). And despite what Hollywood has told you in a thousand films, getting shot in the shoulder can totally kill you. The musket ball actually severed his artery, and Monroe would’ve probably bled to death if a buddy of his didn’t have the guts to tie off the vein. Monroe took two months to recuperate, but after recruiting a few more troops to join the cause, the future fifth president rode back into battle, ready to take down some Redcoats.

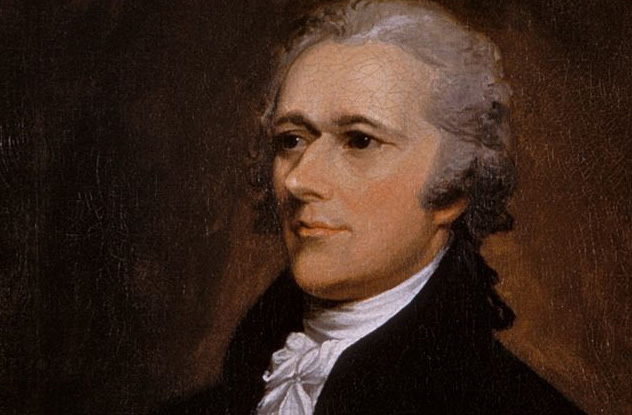

8He Investigated America’s First Sex Scandal

Think “political sex scandal,” and you’ll probably remember Anthony Weiner, John Edwards, and old Bill Clinton. However, American politicians have been feeling frisky since the early days of the republic. As we’ve read before, Alexander Hamilton—the nation’s first Treasury Secretary—was once caught in a rather compromising position, and James Monroe played a key role in investigating and exposing Hamilton’s affair. The story starts in the summer of 1791, when the Secretary first shacked up with a 23-year-old Maria Reynolds. Things got really complicated when Maria’s husband, James, found out and began blackmailing Hamilton. James didn’t care if his wife was having a fling, but he never passed on a chance to make money. This incredibly awkward menage a trois carried on until November 1792, when James Reynolds was busted for forgery. Hoping Hamilton might get him out of trouble, the crook asked the Secretary to pull a few strings, but when he said no, James decided it was time to bring Hamilton down. Hoping to destroy Hamilton, Reynolds contacted his political enemies, the Democratic-Republicans, ready to spill the beans about Alexander’s affair. (Of course, he painted Hamilton as the villain and conveniently forgot to mention the blackmail plot.) Reynolds even claimed Hamilton was involved in his forgery scheme. Concerned, Congress sent three investigators to check out the accusations—Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg, Congressman Abraham Venable, and of course Senator James Monroe. After listening to one side of the story, Monroe and his comrades went to Hamilton. The Secretary denied involvement with Reynolds’s financial scams but did confess to his romantic affair, even handing over a stack of love letters from Maria to discount James’s version of events. Monroe and his compatriots eventually decided Hamilton was innocent of any crimes and agreed to keep the affair hushed up. But Monroe made copies of Hamilton’s letters and gave the documents to both Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton’s political rival, and John Beckley, the clerk of the House of Representatives. Somehow, the letters made their way to the hands of a muckraking journalist named James Callender, who exposed Hamilton’s love life in 1797. As you might assume, Hamilton wasn’t happy, and he had a few choice words for James Monroe. How else had those letters gotten into Callender’s hands if Monroe hadn’t passed them along? Infuriated, Hamilton challenged Monroe to a duel, which the future president accepted. Fortunately, before they could pull their pistols, Monroe’s second convinced everyone to chill out and put down their firearms. Monroe’s second was a lawyer named Aaron Burr.

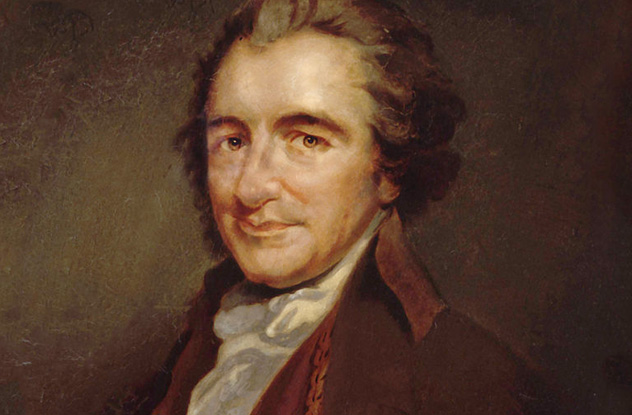

7He Saved Thomas Paine

Though he never fired a rifle or signed the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Paine was one of the most important figures of the American Revolution. A radical thinker and skilled writer, Paine became a national figure after penning Common Sense, a pamphlet that inspired George Washington and the Continental Army to keep up the good fight. Paine was the kind of man who was never truly happy without a little revolution in his life. So when the French decided it was time for a little liberte, equalite, and fraternite, he packed his bags and sailed to Paris. When he showed up in the City of Lights, he was greeted as a hero and granted honorary citizenship. He was the brains behind Rights of Man, a book that defended the French Revolution and slapped the monarchy right in the face. Paine even went so far as to join the French National Convention . . . even though he didn’t speak French. Things got a little uncomfortable once the crazies took over and heads started flying. Paine was not a fan of capital punishment, and after King Louis’s date with the guillotine, the American actually condemned the killers. This didn’t sit well with the men in charge (Robespierre and the Jacobins) who by this point were murdering people for looking at them cross-eyed. Suddenly considered an enemy of the revolution, Paine was arrested in December 1793 and tossed into Luxembourg Prison. Even though the Luxembourg was a converted palace, Paine wasn’t exactly living the high life. Sure, he had plenty of time to write, but he was in constant fear of execution. In fact, Paine was supposed to face the chopping block, but a quirk of fate spared his life. During his time in prison, Paine developed a high fever, and the guards allowed him to open his cell door so cool air could enter the room. Later, officials entered the prison to determine who would be spared and who would be executed, using chalk to mark the doors of the damned. When they reached Paine’s room, they drew a symbol on his door . . . but the cell was open, so they just marked the inside of the door. All Paine had to do now was shut the door, and when the guards came by later to collect their victims, they walked right past his room. In 1794, President Washington appointed Monroe as the US minister to France, and when the diplomat showed up in Paris, one of his top goals was to free Paine from prison. Using all of his ambassadorial powers, Monroe convinced his connections to let the American go, demanding they give the man a trial or set him free. (It probably helped a lot that Robespierre was dead by this point. All that revolutionary fervor had gotten to his head.) When Paine finally crawled out of the Luxembourg after 10 months of terror, he was physically weak and had a nasty abscess in his side. Concerned about his health, Monroe offered to let Paine live in his home until he was feeling better. That was quite the offer because it took two whole years for the writer to regain his strength.

6His Wife Was A Superhero

When Monroe arrived in Paris as the new American ambassador, the French became smitten with his lovely wife, Elizabeth. A New York socialite who married at 16, Elizabeth was incredibly close to her husband, and whenever James traveled on business, he always took his wife and daughter. So when Monroe went to France, his family naturally tagged along, and when they showed up in Paris, they fell in love with French society, adopting both its language and culture. The French loved Elizabeth right back, nicknaming her “la belle Americaine,” and as fate would have it, Elizabeth was able to use this affection to her advantage. When the Monroes moved to Paris in 1794, the Reign of Terror was still going on, and as we’ve read, even supporters of the Revolution—like Thomas Paine—were imprisoned for the smallest of infractions. Two other victims were the Marquis de Lafayette and his wife, Adrienne. The Marquis was a key player in both the American and French Revolutions. Not only did he fight alongside George Washington, he also wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, the French Revolution’s Declaration of Independence. But once Robespierre rose to power, the Marquis had to get out of Dodge. Unfortunately, when he escaped to Austria, the Austrians tossed him into the clink, deeming him a radical. Things weren’t much better for his wife. Since Adrienne was a wealthy aristocrat, she was number one on Robespierre’s hit list. She was arrested, thrown into prison, and threatened with execution. And it wasn’t a bluff. By the time the Reign of Terror ended, Adrienne had lost her sister, mother, and grandmother to the guillotine. Sadly, there wasn’t much Monroe could do. He’d freed Thomas Paine because he was an American citizen. However, Adrienne was French, and if Monroe meddled in French politics, he might lose his diplomatic status. But he wasn’t going to sit around while Adrienne rotted behind bars. He’d have to find another American willing to pull some strings . . . and his wife volunteered for the job. At first, James said it was much too dangerous. Elizabeth countered that the French admired a gutsy gal. Just look at Joan of Arc. Without any other options, Monroe agreed, and Elizabeth went into superhero mode. Hoping to wow the French, she put on a red velvet dress and ermine scarf. She loaded a gaudy carriage with wine and gifts and then rode right through the violent Parisian mob, straight to the Plessis Prison. When she stepped into the street and marched inside the jail, the locals definitely took note, and soon, the French brass heard the minister’s wife was meeting with Adrienne. Feeling the pressure, the revolutionaries freed the Marquis’s wife after 16 months in prison. Adrienne was a pretty awesome lady herself. Once freed, she traveled to Austria, where she voluntarily joined her husband behind bars. There, the couple remained, until Napoleon finally convinced the Austrians to let them go.

5He Was Almost Kidnapped By Slaves

Like many of America’s Founding Fathers, James Monroe had quite a few contradictory ideas about slavery. Sure, he thought it was an evil institution, but he owned 30–40 slaves himself, men and women who worked his 600-acre tobacco farm. He didn’t believe black people were equals with whites, but he did allow his slaves a large degree of freedom (relatively speaking). Monroe opposed immediate abolition, but he encouraged the creation of an African state for freed slaves. (The capital of Liberia, a country colonized by freed African Americans, is named Monrovia after the fifth president.) He tried his best to keep family members together. But, again, he was buying and selling human beings like cattle. The whole “benevolent master” shtick only goes so far. In addition to encouraging the creation of Liberia, Monroe oversaw another key chapter in America’s history of slavery, the controversial Missouri Compromise. However, perhaps the craziest moment in Monroe’s contentious relationship with slavery came in 1800, when he was almost kidnapped by an army of slaves. While Monroe was serving as the governor of Virginia, a slave named Gabriel was planning a revolt. Born in 1776, Gabriel was a blacksmith who quickly became a leader on his Virginia tobacco plantation. His impressive physique—the man stood around 190 centimeters (6’3″)—earned him quite a bit of respect, plus Gabriel was intelligent. His master regularly hired him out to other plantations, and during his travels, Gabriel learned how to read and write. He befriended and interacted with free blacks and poor whites on a daily basis, and since he was always on the move, he was constantly learning new information about the outside world, such as how, in 1791, Haitian slaves had rebelled against their French oppressors. Gabriel decided it was time to follow suit after he was branded for fighting with a white man (literally branded). His plan was to assemble an army of slaves (and even a few freemen, and impoverished whites) and storm the city of Richmond. Allegedly, one of his lieutenants even planned on encouraging the nearby Catawba tribe to join their assault. Once they arrived in the capital, they would march on the governor’s mansion, take Monroe hostage, and demand the freedom of Virginia’s slaves. At first, it seemed like the plan might work since Gabriel was able to recruit conspirators from plantations across the state. Only when August 30, D-Day, rolled around, a massive thunderstorm flooded several important roads and bridges. Gabriel decided to attack the next day, but before he could launch the invasion, a few slaves lost their nerve and alerted the whites as to what was happening. When word reached Monroe, the governor sent out the state militia, and soon, nearly 30 slaves were hanging from the gallows. As for Gabriel, he managed to elude his pursuers until mid-September when another slave, hoping to collect the bounty and buy his own freedom, ratted Gabriel out. (Instead of receiving the $300 reward, the slave only got $50.) Gabriel was sentenced to death on October 6, but he convinced the judge to let him die on October 10, alongside several of his friends. When it came time for the execution, authorities split the men up, sending Gabriel’s friends to die in two separate locations. So when the brave resistance leader dropped through that trap door, he died completely alone.

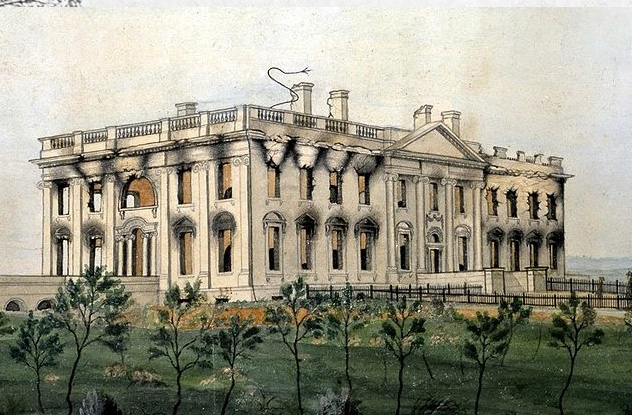

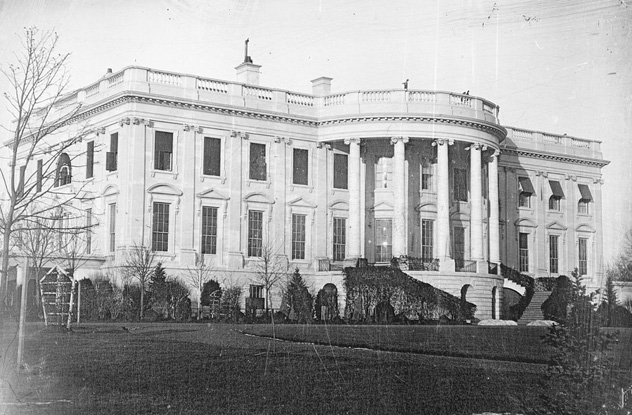

4The Day The White House Burned Down

On August 20, 1814, Secretary of State James Monroe saddled up his horse and rode out of Washington, DC, with a small scouting party. The British were coming—again—and Monroe needed to know where the Redcoats were headed. Secretary of War John Armstrong was positive the British wouldn’t attack the capital, but Monroe wasn’t so sure. When Monroe reached Benedict, Maryland,—several miles from DC—he spied 4,500 troops, battle-hardened vets who’d just returned from the Napoleonic Wars. While Monroe forgot to bring his spyglass and couldn’t properly gauge how many troops were on the way, it was pretty clear they were headed straight for Washington. Even though it was 1814, the US and Great Britain were currently slugging it out in the so-called War of 1812. The Americans were fed up with the British kidnapping their sailors and interrupting trade with France, so the US declared war. At first, most of the battles took place in Canada, but soon, the fighting made its way southward. Now, the British were just a few days away from President James Madison and the executive mansion. Knowing the Brits were probably planning on a barbecue once they reached the capital, Monroe sent a warning to DC, advising the clerks at the State Department to take “the best care of the books and papers of the office.” Thanks to Monroe’s warning, the clerks were able to rescue several key documents like the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Independence. Monroe’s scouting party took a few shots at the invaders, but things didn’t get really interesting until the militia showed up. On August 24, 6,000 poorly trained Americans arrived at Bladensburg, Maryland,—a town on the outskirts of DC—ready for battle. Even President Madison showed up, sporting two pistols on his gun belt. In fact, the overeager president almost rode into the British camp, but fortunately, a scout stopped him just in time. Unfortunately, this is where our boy Monroe made a major mistake. As Secretary of State, Monroe wasn’t supposed to order troops around, but for some reason, he thought it was a good idea to send the second line of soldiers farther back, away from the battle. That majorly backfired when the disciplined British troops sent the first line of unorganized Yankees running, and there was no one there to back them up. Sure, the Americans outnumbered the Brits, but this was a well-trained army versus a militia that trained once a year. Plus, the Redcoats were launching Congreve rockets, wildly inaccurate but terrifying missiles. In fact, some of these rockets actually zoomed right over Madison and Monroe. It was about then that the President decided it was time to get off the battlefield. The rest is history. The British burned down the White House, the Capitol, the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court. Madison and Monroe fled DC, and eventually, the War of 1812 came to an end when both sides got tired of fighting and signed a treaty in December 1814. As to how the White House was rebuilt, we’ll talk about that a little later.

3He Was Pretty Good At Stopping Duels

After James Monroe was elected president, he took 15 weeks out of his schedule to visit cities across the US. When the Monroe goodwill tour showed up in Boston, a local newspaper officially declared Americans were living in the “Era of Good Feelings.” For the first time in a long time, Americans weren’t particularly worried about European politics or British invasions. And since there was only one dominant political party at the time (the Democratic-Republicans), there wasn’t a lot of bipartisan bickering. In fact, when Monroe ran for president, he earned every single electoral vote except one, and that’s because somebody thought George Washington should be the only president ever unanimously elected. Of course, just because this was the “Era of Good Feelings,” that didn’t necessarily mean everyone got along. For example, the British and French weren’t on particularly good terms, especially since the two nations had been at war pretty much constantly between 1793 and 1815. And that’s not even counting the American Revolution or French-Indian War. So even though the two countries were technically at peace during Monroe’s presidency, there was a lot of bad blood between the Brits and the French, and sometimes, tensions had a way of flaring up, even during White House dinners. It was your typical executive banquet, and President Monroe was entertaining both British minister Sir Charles Vaughn and French minister Count de Serurier. At first glance, everything was going smoothly until Sir Vaughn glanced up and noticed the Count was biting his thumb. In fact, every time the Englishman made some sort of comment or launched into a speech, the Frenchman started chewing on his thumb. Evidently, this was quite the insult back in the day, and the British minister eventually lost his temper. “Do you bite your thumb at me, sir?” Vaughn asked. “I do,” responded de Serurier. And then in typical 19th-century fashion, the two men got up from the table, marched out into the hall, and pulled out their swords. But before they could run each other through, Monroe burst into the hallway, pulled out his own saber, and told the ambassadors to cool it. Instead of kicking off history’s greatest three-way swordfight, the Europeans put their weapons away and left the White House, slightly embarrassed but still alive.

2Showdown In The Oval Office

If we’ve learned anything about James Monroe, it’s that the man never backed down from a fight. Even as a 60-something president, Monroe wasn’t afraid of throwing down, even if his rival was over a decade younger, like William H. Crawford. Born in 1772, Crawford was a pretty big deal, politically speaking. Before his death in 1834, Crawford served as a senator, the minister to France, and the Secretary of War. In fact, there’s a real possibility he could’ve become president, but he decided not to challenge Monroe in the 1816 election. Instead, he served on Monroe’s cabinet as Secretary of the Treasury, where he came into constant conflict with War Secretary John C. Calhoun. Crawford and Calhoun hated each other’s guts, so when the War Department was forced to scale back and fire a few Army officers, the Treasury Secretary knew Calhoun would probably can all of Crawford’s friends. Hoping to help his buddies, Crawford went to the president. True, Monroe usually sided with Calhoun, but hey, Crawford had dropped out of the 1816 election so Monroe could win the presidency. The man owed him a favor. Monroe didn’t respond to Crawford’s message, and the Treasury Secretary was getting angry. Ready for a showdown, Crawford stormed into the White House, shouting, “I wish you would not dilly dally about it any longer, but have some mind of your own and decide it so that I may not be tormented with your want of decision.” Obviously, you can’t talk to the president this way, and Monroe told Crawford to watch his mouth. The Secretary flipped out, called Monroe an “infernal scoundrel,” and raised his cane, ready to strike. But as Crawford made his way across the room, the 60-something president reached into the fireplace, pulled out some heavy-duty fire tongs, and told Crawford to get lost. Suddenly, the Treasury Secretary regained his composure and apologized for, you know, trying to bash in the president’s brains. (Even in Washington, that’s generally considered bad form.) The two shook hands, and Crawford went on his way, but the Secretary never returned to the Monroe White House. If you’d tried to kill your boss, you’d probably feel pretty embarrassed about it, too.

1He Refurbished The White House And Went Into Debt

When James Monroe took the Oath of Office in 1816, he had one little problem. There wasn’t any furniture in the White House. Just a few years before, the British had set the whole thing on fire. In 1815, architect James Hoban—the man who built White House I—was hired to rebuild the executive mansion, but still, there wasn’t anywhere to sit. That’s why one of Monroe’s first acts as president was to petition Congress for government funds to redecorate the White House. Monroe absolutely loved French fashion, maybe because he once served as minister to France, and he filled the White House with pricey, gilded furniture straight from Le Havre. Monroe originally wanted mahogany furniture, but the firm in charge of buying all the chairs and tables refused. As they explained, “Mahogany is not generally admitted into the furniture of a salon, even at private gentlemen’s houses.” So while he was something of a Francophile, Monroe wasn’t exactly up to date on all the latest trends. Some of Monroe’s furniture still exists today. If you visit the Blue Room, you’ll see some of the original gilded furniture imported from France, as well as a clock and an armchair, all dating back to 1817. But while Monroe certainly spruced up the White House, his stint as an interior decorator caused him quite a bit of trouble. Congress eventually gave Monroe $50,000 for his furniture fund, but the president quickly ran out of money, forcing him to dip into his personal bank account and even donate some of his own furniture to the White House cause. It didn’t help that the man in charge of the furniture fund, one Samuel Lane, was either a crook or an idiot who messed everything up. For example, on one occasion, Lane used a good chunk of the furniture fund to buy 1,200 bottles of French wine and champagne. Thanks to Lane’s mishandling of the money, Monroe soon found himself in debt—and in big trouble. When Lane died, Congress found quite a few discrepancies in the furniture fund and immediately investigated Monroe, suspecting some sort of swindle. After examining Monroe’s paperwork, Congress decided the president was innocent of any crimes, but that didn’t prevent their relationship from becoming even more awkward. Monroe retired after his second term, and the man was still broke thanks to the furniture debacle. Desperate for dinero, Monroe started asking Congress for money, reasoning they should reimburse him for all the times he’d used his own cash. Congress finally gave in, but Monroe’s last years were still kind of bleak. In 1830, he was forced to sell his plantation and move to New York with his daughter. Eventually, at the age of 73 and still broke, James Monroe died in 1831, and just like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, Monroe died on the Fourth of July. Once upon a time, Nolan Moore was a high school history teacher. He’s also written several articles about America’s founding fathers. (And he’s also a shameless self-promoter.) If you want, you can friend/follow Nolan on Facebook, or you can send him an email.