10 Blood-Stopping

The Ozarks region of Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas has a tradition of “power doctors,” who are purported to be able to cure illness and disease through supernatural means. One of their most vaunted techniques is known as blood-stopping, by which the “unnatural” flow of blood is staunched by magic, usually with the recitation a verse from the Book of Ezekiel: “And when I passed by thee, and saw thee polluted in thine own blood, I said unto thee when thou wast in thy blood, Live; yea, I said unto thee when thou vast in thy blood, Live.” One Georgian woman in the 1960s even claimed to be able to use the power of blood-stopping by reciting the verse over the telephone, substituting the word “thee” with the patient’s name. Another variation used by a blood-stopper in Missouri was even simpler: “Upon Christ’s grave three roses bloom, Stop, blood, stop!” Some blood-stoppers have even claimed to be able to exert their influence on farm animals and in one notable case, on a piece of meat. A skeptic was having dinner with a self-proclaimed blood-stopper and challenged him: “We’ll just let ya’ try your luck on this beef.” The blood-stopper replied, “All right, but it’ll ruin yer beef, man.” According to the story, the skeptic ended up going hungry. “They killed it’n stuck it. It never bled a drop. Blood stayed right in th’ flesh an’ ruined it. Couldn’t eat it.” Interestingly, a parallel tradition existed among the Saami people of northern Norway, which would later be adopted by non-Saami practitioners of folk magic and persisted into the modern day. Like in the Ozarks, religious commandments were often used to staunch the flow of blood, often including a reference to the Trinity: Stop blood! As the water stopped In the river of Jordan In the three holy names God the Father and Son And the Holy Spirit.

9 Concealed Items

Although 160,023 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868, there is little remaining in terms of the clothing they wore. This odd fact is likely linked to the secretive folk magic tradition of concealed items. In the bizarre and exotic environment that the convicts found themselves thrust into, they leaned on superstitions to protect themselves from hostile supernatural forces. They achieved this through an old British magical tradition—concealing clothing, shoes, toys, trinkets, and dead cats in houses and other buildings in order to protect the occupants from evil spirits. In 1980, tradesmen renovating Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks discovered two convict shirts hidden in the structure of the building, and numerous examples have been discovered since. One of the most interesting was the discovery of a child’s shoe hidden in a pylon of the Sydney Harbor Bridge. According to Australian historian Ian Evans, it was “concealed by a builder or stonemason to protect against evil forces.” There is no written documentation of the secretive practice, and it has only been rediscovered with the finding of old boots, shoes, tattered garments, children’s toys, and the bodies of dead cats found hidden away in the walls of colonial-period homes. These items were almost invariably hidden in out-of-the-way parts of the house such as behind walls, up chimneys, and in attic crawl spaces, which were believed to be weak points through which malevolent forces could enter houses. It is believed that this tradition was observed in parts of Australia until at least the 1930s, and thousands of such protective items still lie hidden in houses, with their occupants none the wiser. One sign of their presence is evidence of evil-averting marks or apotropeia, mystical marks scratched next to windows or doors, on fireplace lintels, or in roof cavities.

8 Fishers’ Magic

Men who work on the sea away from civilization have long been known to maintain superstitions and rituals to ensure their safety on the water, and these have persisted in the modern era. The 19th-century fishermen of Gloucester, Massachusetts, were eager to avoid individuals, vessels, and objects identified as “Jonahs,” which were cursed with bad luck. A spell of poor catches could lead to a person being identified as a Jonah, possibly leading to him being kicked off a vessel. In ambiguous cases, a Jonah could be identified by the ship’s cook putting a nail, a piece of wood, or a lump of coal in a loaf of bread. Whoever got it was labeled a Jonah, unless of course he was known to be a good fisherman. Certain activities were also deemed Jonahs, though individuals often expressed very different opinions over which ones were. These included making toy ships while onboard, anchoring in an inauspicious fashion, or cleaning one’s deck while on the fishing waters (or allowing it to get dirty). Soaking mackerel in a bucket was seen by some as a particularly egregious Jonah, because, “So long as you soak them in a bucket you will never get enough to soak in a barrel.” Gloucester fishermen believed in a number of strange superstitions and practices, such as whistling into the wind or sticking a knife into the aft side of the mast to summon a breeze. Some wore earrings that were believed to improve eyesight, and many others would carry lucky talismans such as fish or animal bones or horse chestnuts. Putting potatoes in one’s pockets protected against rheumatism, and wearing nutmeg around the neck cured scrofulous. One interesting custom was observed in the Cape Cod region when a fish was being dressed. One man, the header, would decapitate the fish and hand the body to the splitter. If the fish’s body continued to wriggle, the splitter would ask the header to kill the fish, which the header would do by striking the decapitated fish head. According to one Gloucester fishing captain, “It is a singular thing, but it is surely true, that when the head is treated in this manner the body always straightens out.”

7 Kaji Kito

In the late Edo period of Japan, there was a steady increase in the belief in folk religion, particularly seen in attendance at temples and shrines dedicated to kaji kito, meaning “magical intercession.” The elite looked askance at the development, condemning the rise of inshi jakyo (“immoral and deviant religion”). Eighteenth-century Confucianist Nakai Chikuzan was particularly critical: Auguring weal and woe and praying for healing, divining propitious directions for a physician, or [telling people to] stop using medicines, thus leading to their deaths; worshiping Ebisu and Daikoku as a pretext for lust and wickedness, making the shrine Tenmangu a medium for lasciviousness, substituting [the bodhisattva] Kannon in place of midwives; and with reckless talk of badgers and foxes and baseless fictions about tengu, imputing all kinds of marvelous wonders to insignificant kami and trivial buddhas; divining dreams of kami and buddhas and huckstering worthless drugs and base concoctions, performing divinations of mutual compatibility for men and women, divinations of physiognomy, swords, the geomancy of houses—these kinds of deviant beliefs are rampant, and nothing but techniques to confound the ignorant masses. But these places served a purpose, as people increasingly began to move into cities for economic reasons and lost contact with the communal folk traditions of their original villages. Kitoji (“intercession temples”) appealed to an increasingly urbanized population by merchandising their religious and magical services. One popular 1814 guidebook called Edo Shinbutsu Gankake Chohoki (A Treasury of Invocations to Deities and Buddhas in Edo) detailed the shrines and temples of the area and their respective magical specialties—healing toothaches or head pains, curing smallpox, protecting against burglars or snakes, ensuring good marital relations, and protecting the shaven part of infants’ heads. The increasing burden on religious organizations to meet the needs of their clients encouraged temples and shrines to put on kaicho festivals, when religious statues or other items would be put on display while offerings were received. These were described in the Edo Hanjoki in 1832: The deities and buddhas vie with each other to come immense distances from all directions to gather at Edo. It’s a toss up whether the deities and buddhas bring fortune to people, or whether people bring fortune to the deities and buddhas. [ . . . ] Sweat falls like rain as people fill the roads en masse, much like ants gathering at a pile of rice bran. At the place where the image arrives, a temporary enclosure is built, a curtain is hung, and amid solemn, reverent, magnificent adornment, miracles are sold.

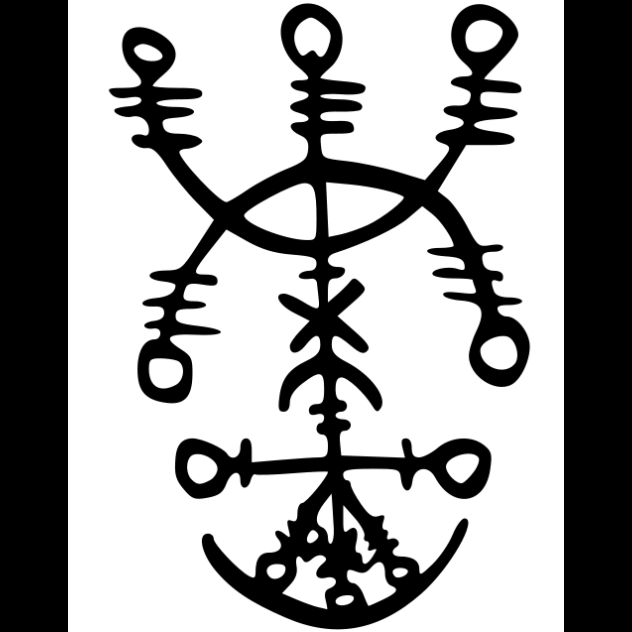

6 Galdrastafir

Derived from mystic traditions and pagan beliefs from the Middle Ages, galdrastafir were Icelandic sigils designed to control or influence the world through magic. They have their origins in Norse runes and pagan mythology but also incorporated Judeo-Christian elements. They may have existed since the 1400s but became most popular from the 17th century onward, and most of the grimoires featuring galdrastafir date from that period. They were used by so-called galdramenn, those who had received an education in Scandinavia and Germany with the intention of becoming clergy only to come back and become magicians instead, using their literacy to amaze and enchant the generally illiterate population. There were a number of different forms of galdrastafir. The oldest are called asymmetrical, usually consisting of lines intersecting with other lines or small shapes with hidden or arcane meaning. Symmetrical galdrastafir look like cartwheels or snowflakes, and some combine Christian and runic imagery. Runic galdrastafir are strings of rune characters, the meaning of which is generally unknown, while seal or insignia galdrastafir resemble seals in European occult texts and usually reference Christian leaders, monarchs, and angels. The most elaborate and beautiful were the superstaves, sometimes called “rood-cross,” generally used for protection against evil forces. While some galdrastafir simply effected luck or protection from evil, many others had a specific purpose. Many were purported to affect human relationships. One ensured that, “A girl will love you. Carve this stave in the palm of your hand with your saliva and then shake her hand.” Many others were designed to give the user assistance in economic activities, support in legal redress, influence over the weather, or an advantage in cards or wrestling. There are a few recorded instances of malicious spells, though they aren’t particularly deadly. Examples include causing a victim to fart or vomit uncontrollably, or fall off a horse. The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft has provided a guide to many galdrastafir and their uses online.

5 Witch Smellers And War Diviners

The Nguni people of South Africa’s Cape region, such as the Zulu and Xhosa, had many individuals within their societies who fulfilled the role of healer-diviners, known generically as amagqira or izangoma. These included izanuse (“omniscient diviners”), amaxhweli (“herbalists”), nolugxana (“doctors of the medicine digging-stick”), awemilozi (“ventriloquists”), ambululayo (“revealers”), awomhlahlo (“appeal diviners”), awamathambo (“bone diviners”), aqubulayo (“extractors”), awezipili (“mirror diviners”), and awemvula (“rainmakers”). One prominent magical role in the Nguni societies was that of the igqirha elinukayo (“witch smellers”) who were used to “smell out” witches and those using foul magic to influence rivals or enemies. They also acted as spirit mediums and were turned to for supernatural aid when sickness or disaster struck. Christian missionaries of the time had a dim view of them, calling their spiritualism “jugglery and incantations” and saying of their healing abilities: “Attempting to save life as frequently destroy it by cramming down a multitude of drugs without stopping to watch the effects of one.” Another figure who distrusted the witch smellers was the fearsome Zulu king Shaka, who saw them as a threat to his power base. (While he could not be accused of witchcraft, his subordinates and associates could.) So he centralized the whole business, declaring that he had immunized his entire army against accusations of witchcraft and taking the title “Dream Doctor” to assert his spiritual authority over the witch smellers. During the Frontier Wars between the English colonial administration and the Xhosa people from 1846 to 1878, war diviners (amatola or itola) played a major role. War herbalists would create a concoction out of a plant called umabophe (meaning “to tie up”), and sprinkle it over the bodies of Xhosa warriors to make them invulnerable or over a flooding river to allow warriors to cross safely. The diviners would also make incisions in warriors’ skin and rub in animal fat, meant to make them fearless. After the wars ended, the war diviners mostly returned to life as simple herbalists. War divination is no longer practiced.

4 Cunning Folk

“Cunning folk” was an English phrase to refer to individuals who engaged in beneficial magical practices such as healing the sick, removing curses, identifying wrongdoers, and inducing love. Such practices date back to the Dark Ages, and the expression “cunning folk” can be traced to the Anglo-Saxon word cunnan, meaning “to know.” They enjoyed a boom in popularity following the Reformation, taking over the role of healing and supernatural protection that had once been occupied by the Catholic clergy. It was in this period that people began to distinguish between malicious black magic and beneficial white magic, though both were considered anathema to mainstream religion at the time. While there was undeniably a popular demand for their services, cunning folk operated at the fringes, constantly under threat of persecution. Some were tried under witchcraft laws, but many more were dragged before ecclesiastical authorities and accused of peddling the sort of superstition that the Church of England had been established to eradicate. For cunning folk in the upper echelons of society, knowledge of white magical arts such as astrology, alchemy, and necromancy were within financial and educational reach, but for cunning folk among the lower classes, a simple demonstration of literacy and a grasp of occult concepts or literature was enough. Many cunning folk worked not for income but rather to increase their status within their community. Knowledge of magical traditions was passed down within families or from master to disciple, as well as simply picked up from observing the techniques of other cunning folk. Services provided by the cunning folk were varied and involved diverse incantations, preparations, and magical rituals. Thieves were identified via a ritual involving slips of paper with the names of suspects, slotted one by one into the hollow section of a key while a cunning man or woman held a Bible. When the Bible began to “wag” and fell out of their hands, the culprit was identified. Healing magic was performed with the use of Catholic prayers or written charms, which were impressively arcane to the usually illiterate population who used these services. Meanwhile, “witch-bottles” or “bellarmines” helped to protect against the influence of malevolent magical practitioners. They were filled with potions made of hair, urine, and pins and then buried or burned as a potent form of counter-magic.

3 Powwowing

Derived from older traditions and brought to the US by German settlers, powwowing (brauche in German, spoken by the Pennsylvania Dutch) is a religious and magical tradition practiced among the Pennsylvania Dutch (again, of German heritage), particularly among the “plain people”—Amish, Dunkers, and Mennonites. The tradition is believed to derive from pre-Reformation practices that were condoned by the Catholic Church but then driven underground by the Protestants. The magic performed a number of protective and healing functions, such as counteracting hexes or curing illness (though if a powwow healing did not achieve results, the powwowwer would often blame it on the insufficient faith of the patient). Most powwowing incantations are taken from the Bible, with certain passages believed to have particular powers to exert supernatural influence, including the same Ezekiel 16:6 passage used by the blood-stoppers of the Ozarks. Many incantations also call on the intercession of the saints, and some prominent powwowwers came to be regarded as saints in their own right. One such person was the German immigrant Anna Maria Jung, who retreated into the mountains after the death of her husband in the American Revolution and became a holy woman. She was called “Mountain Mary” or “Barricke Mariche” by the locals. Another potent source of incantations was written by another German immigrant, John George Hohman, in 1819—Der lang verborgene Schatz und Haus Freund (The Long Lost Friend). It contained a variety of potent spells and practices derived from the Bible, occult sources such as the German charm book Romanusbuchlein, and Egyptian Secrets, a book of magic compiled by 13th-century Swabian Dominican monk Albertus Magnus. Hohman claimed that his book was in itself a powerful protective amulet and also contained a variety of useful spells, such as the following: A GOOD REMEDY FOR THOSE WHO CANNOT KEEP THEIR WATER—Burn a hog’s bladder to powder and take it inwardly. A GOOD REMEDY TO STOP BLEEDING—This is the day on which the injury happened. Blood, thou must stop, until the Virgin Mary bring forth another son. Repeat these words three times. TO EXTINGUISH FIRE WITHOUT WATER—Write these words on each side of a plate, and throw it into the fire and it will extinguish forthwith: SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS Another more dangerous powwowing text is the mysterious The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, which is believed to contain incantations relating to black magic and the summoning of spirits. Generally, powwowers would strenuously deny practicing black magic or hexerei. In the words of 19th-century powwower Peter Bausher: “I only try to cure people and help the afflicted. Heaven knows there is enough suffering in the world.”

2 Granny Women

There were few trained physicians in the Appalachians in the 19th century, so people usually turned to the services of individuals whose practices lay on the edge between folk medicine and folk magic, usually known as “granny women,” or in the case of men, “yarb doctors.” They were essentially herbalists, collecting and preparing natural pharmaceuticals with organic or inorganic properties that could help to alleviate the symptoms of sicknesses. While they could not cure diseases, they saved lives by reducing the severity of the symptoms. They also played an extremely important role as midwives. Medical doctors were usually too far away to respond quickly to a childbirth in the Appalachian hills, while granny women were closer and willing to spend far longer periods of time tending to a woman in labor. They provided psychological support, in no small part through a belief in a number of mystical rituals to help induce a healthy birth. A woman would be given her husband’s hat to hold on to, bringing him symbolically into the room even though the mores of the time left him pacing outside. Labor pains were dealt with by placing an axe or knife under the bed, “cutting” the pain, while every door and window of the house would be opened, symbolizing the opening of the birth canal. Herbal remedies were used to assist the birth, such as raspberry tea to relax uterine muscles, blackberry to avoid hemorrhaging, and slippery elm bark tea to speed delivery. They could also give the mother a tablet of laudanum, morphine, or quinine if things seemed really grim, as such drugs were available over-the-counter before 1906.

1 Hoodoo

The African-American folk tradition of hoodoo (otherwise known as Conjure) is distinct from the African diaspora religion of voodoo (or Vodou), though they both have origins in West Africa. While voodoo is a religious system, hoodoo is a magico-religious system of beliefs that seeks to use spiritual forces to exert influence over the world, for both good and evil. Hoodoo first emerged in the southern United States as a belief system among slaves and the descendants of slaves taken from the tribes in what is now the Congo, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. These people brought their diverse traditions with them to the New World, which became voodoo and hoodoo. Hoodoo also borrowed elements from Native American beliefs, as well as Northern European cunning folk traditions. Some believe that voodoo was able to develop into a more established religious tradition by co-opting the saints and sacraments of Catholicism. American Protestantism did not tolerate such heterodoxy, and African folk beliefs developed in secrecy into a folk magical tradition, which could be practiced with the acquisition of esoteric knowledge without necessarily being initiated into a theological tradition. Hoodoo provided a way for slaves to exert some measure of control over their environment. Conjurers were even believed to be able to provide supernatural assistance for escaped slaves, able to throw pursuing dogs off track by sprinkling graveyard dust or by causing the dogs to stop and bark at trees. If a slave was recaptured, hoodoo was said to exert a magical influence over the white slave owners, impelling them to be lenient. Of particular importance was the art of rootwork, an herbalistic art with origins in West Africa but also incorporating Native American knowledge of New World herbs (though many African plants were brought to the New World by slaves themselves). These practices sometimes changed through adoption. For example, the amaranth plant, which was used as an astringent by Native herbalists, was used by hoodoo conjurers to make a person fall in love when combined with honey and a dove’s heart and eaten. The most potent root may have been the High John the Conquer root, also known as bindweed or jalap root. Some hoodoo scholars have suggested that its magical power derives from resembling a black man’s testicle, but others believe this explanation to be erroneous. Originally used as a medicinal plant in Mexico, it would become the most important magical root in hoodoo tradition. Conjure bags, otherwise known as gris-gris bags, mojo bags, lucky hands, or nation sacks, also played an important role. Filled with roots, plants, minerals, or the powered remains of animals, these bags served as a connection to the spirit world and could provide love, protection, luck, and healing. One potent conjure bag ingredient was a bone from a black cat that had been boiled alive, believed to serve as a counter-magical ward or to allow the user to fly, become invisible, or cure illness. Hair, nails, or needles from a person could be used to target a particular individual, while graveyard dirt could draw power from the dead. David Tormsen once found a child’s shoe on the road and left it in his freezer for six months in the hopes of magical protection. Didn’t work. Email him at [email protected].