Rare remains also expose prehistoric landscapes, unknown industries, and how humans were a bigger extinction force than previously thought—one that sometimes only left traces in genes and unique bones.

10 Turtle Tunes

At archaeological sites in North America, turtle shells are not rare. For many tribes, the reptile was a food source, so past researchers dismissed the shells as the remnants of an ancient dinner. In 2018, a study focused on turtle remains from Tennessee. Most of the partial shells belonged to Eastern box turtles and revealed a completely different use for the reptiles—musical instruments. The belief that some were rattles was not entirely new. A few other shell shakers have turned up across North America. The unearthing of more at several Tennessee sites proved that ancient animal remains should not be taken lightly. The rattles might have been sacred due to a symbolic connection to turtle myths. Very likely, this importance was injected into ceremonies through musical rhythm.[1] That is a far cry from what archaeologists originally thought turtle shells meant at tribal sites. This sobering possibility could one day prompt the reexamination of other artifacts that usually suffer expert assumption.

9 Catastrophic Clues In Fat

When global temperatures suddenly plummeted about 8,000 years ago, the results must have been catastrophic for early farmers. Archaeologists interested in this event had no real information about what agriculturists went through. In 2018, an archaeological treasure delivered a good glimpse. The ruins belonged to Catalhoyuk in Turkey. As one of the oldest cities ever, it has produced many historical finds. As far as the global cooling was concerned, researchers looked at the settlement’s pottery and especially those pieces that once contained meat. Fat residues from cattle and goats revealed that the cooling event 8,000 years ago caused an extreme drought. The fat retained the chemical signs of leaner, thirstier animals eating drought-stressed plants. This chemical signature was the first evidence proving the temperature drop event. The animal fat also showed that the people of Catalhoyuk adapted. For one thing, they increased their goat herds because goats flourish better than cattle under drought conditions. Butcher marks on animal bones also suggested that the slaughtering process was refined to salvage as much meat as possible.[2]

8 Roman Whalers

In 2018, researchers visited three Roman fish processing sites near the Strait of Gibraltar. Among the finds were ancient bones too large for normal fish. With researchers suspecting that they were whale remnants, tests quickly followed. If proven as such, it would change what history knows about the fish sauce–obsessed Romans. The results showed that the skeletal bits belonged to a dolphin, an elephant, and indeed, two species of whales. Not only did this indicate that the Romans had a booming whaling industry but it also taught biologists something else. The two types, gray whales and North Atlantic right whales, are species that migrate along coasts but are not found in European waters today. The bones proved both were present in the Mediterranean during Roman times, solving one question about the species’ original distribution. However, the discovery opens up a strange mystery. The Romans were avid food writers. However, among the many fish and seafood dishes described, none mention whale meat.[3]

7 Penguin Mummies

In 2016, researchers investigating Antarctica’s Long Peninsula found a disturbing sight—hundreds of dead penguins. The mass grave was not the result of a modern disaster. It was around 750 years old, and the birds were naturally mummified. Antarctica is littered with the bones, feathers, and freshly dead bodies of Adelie penguins. However, to find such a huge deposit of mummies is exceptionally rare. Even more scarce was the large number of mummified chicks. In 2018, a nearby nesting site revealed what had happened. It was not a single event. The colony was hit twice by extreme snow and rain—750 and 200 years ago. Both caused massive fatalities, and floodwaters swept the bodies downhill into the graveyard. Adelie penguins are not threatened, but they die in massive numbers when exposed to extremely wet weather. The discovery of the graveyard showed that they fared no better in the past. Unfortunately, the future looks no better. Global warming experts predict increased snow and rain in Antarctica.[4]

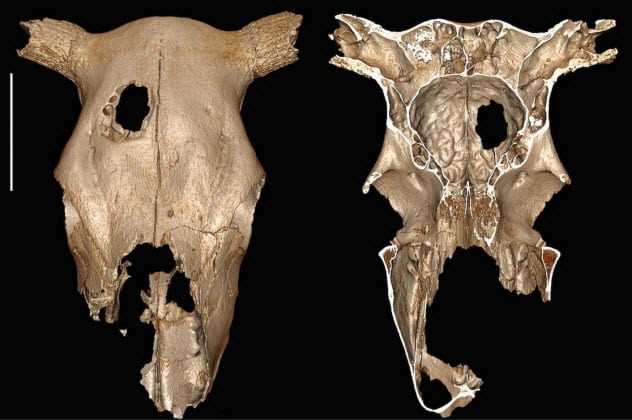

6 Neolithic Surgery Practice

In western France, excavations at a Neolithic site ran from 1975 to 1985. Among the finds was the skull of a cow that lived around 3400–3000 BC. A hole in the skull was dismissed as an injury likely caused by a scuffle with other cattle. In 2018, researchers published their findings after taking a second look at the skull. The 5,000-year-old hole was not caused by another animal’s horns as it lacked the trademark fractures of a violent smash. Instead, there were scrape marks. They resembled those on skulls from people who had undergone an ancient brain surgery known as trepanation. It was also determined that the 6.4-centimeter (2.5 in) by 4.6-centimeter (1.8 in) puncture was made by stone tools. The purpose of the surgery remains unclear. Either somebody decided to save a sick cow, making it the earliest-known veterinary surgery, or the head was used to train a surgeon for human operations.[5] Whatever the reason, the discovery remains the oldest evidence of a medical procedure performed on any animal.

5 Unique Wolf

Canada’s Klondike region is known for a historical gold rush and lots of snow. In 2016, miners discovered a different kind of prize. One was the front half of a caribou calf and the other, a wolf puppy. Both youngsters were naturally mummified and dated to the last ice age. The pup, in particular, made researchers giddy. Not only was it the first wolf recovered from an ice age but the animal was also remarkably well-preserved. It is rare for hair, skin, and other soft tissues to survive long after death. However, the wolf was so pristine that it appeared almost freshly dead or asleep. The pair of animals was only made public in 2018. There remains a lot to be explained about what killed them, how old they were, and what they ate. Genetic tests on the 50,000-year-old babies could reveal their closest living cousins as well as insights into ice age herds and packs.[6] A strong clue about their environment hinged on their preservation. The fact that skin and hair mummified successfully suggested that they lived on a cold, dry tundra.

4 Mayan Big Cat Trade

At the Mayan site of Copan in modern-day Honduras, a young woman was buried in AD 435. Several large animals were included in the tomb, but the most remarkable was a complete puma. In 2018, the cat’s remains and a huge presence of other puma and jaguar skeletons at Copan revealed something interesting. The tomb cat—and most of the others—was domesticated. There were simply not enough wild ones in the region to account for the thick layers of bones discovered in some places. The skeletons of the ritually slaughtered felines showed that few ate a wild diet, meaning that the predators were raised on human food and were probably kept in cages. Analysis of their pelts showed that some came from other places. The revelation of a vast trade network dealing in big cats and other animals was unexpected. This was something that experts believed only happened centuries later.[7]

3 The Grave Gibbon

In 2018, a burial chamber was opened in China. Located in the Shaanxi Province, it was around 2,300 years old. The tomb might have been the Lady Xia’s. Her grandson, Qin Shihuang, became China’s first emperor and the man who ordered the construction of the iconic Terracotta Warriors and the Great Wall. The illustrious family link was not the thing that excited researchers the most. The grave also held the bones of predators such as a bear, leopards, and a lynx. The showstopper was an ape skull. It was incomplete but carried enough traits to be identified as a gibbon. Since gibbons were kept as pets by the Chinese elite, this individual could have been the property of Lady Xia. Incredibly, the ape was unknown to science. The extinct gibbon was named Junzi imperialis and challenged a big belief about human-primate interactions. Every ape species today is threatened by human activities, but none was believed to have gone extinct because of it. Junzi represents strong evidence of the first primate to disappear due to human pressure.[8]

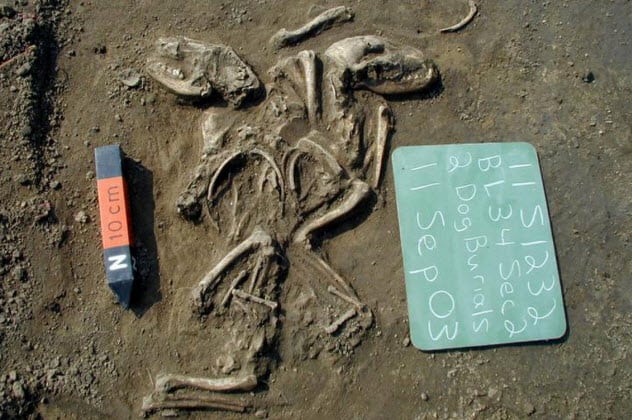

2 Americas’ Native Dog

The ancient Americas once had indigenous dogs. A study done in 2018 looked into their extinction, yielding fascinating genetic facts and a tragic bigger picture. The tests on 71 original American canines became the first evidence against a popular theory that they descended from local wolves. The dogs were brought by people who settled the region over 10,000 years ago. The feisty creatures lived for millennia but could not survive the arrival of the Europeans. New canine diseases like rabies likely killed large numbers, and the colonists also actively eradicated the native dog. The extermination was so successful that little of the animals’ genetic makeup remains today. Around 5,000 modern dogs were sampled, and only five had a minuscule number of ancient genes. The only other trace of the Americas’ first canines manifests as a common tumor that still affects dogs. Canine transmissible venereal tumors (CTVT) is a genital cancer that infects dogs during mating. Incredibly, this cancer still carries the genome (genetic code) of the first ancient dog who developed it.[9]

1 Animal Unlike Any Other

The fossil record can produce some strange things, but nothing compared to the so-named Ediacaran organisms. They first appeared at an Australian fossil site in 1946. Soon, more showed up and a basic picture about them began to form. They resembled plants and sometimes grew fronds or tubes as tall as a man. Many species developed and became common in the ocean half-a-billion years ago. Despite their looks and availability, decades of analysis failed to identify the life-form as algae, a type of fungus, or an unknown branch of life. In 2018, it turned out that researchers were both right and wrong. It was not a plant, but probably an animal unlike any that ever walked the Earth. Its unique anatomy was so confusing that experts used artificial intelligence to solve its evolutionary place.[10] A computer program found that the organisms belonged to no known group of life. There was a small victory, though. The program managed to slot them between sponges and highly developed animals with digestive systems. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages