10Jean Lanfray And The Absinthe Murders

If absinthe is associated with anything, it’s the questionable allure of its supposed hallucinogenic properties, its appeal to a certain bohemian crowd, and its potential for addiction and destruction. That’s the story that’s gone along with the drink for decades, and it all got its real momentum with some incredibly unfortunate events in a very unlikely place. Commugny is a rural town in Switzerland. It’s a fascinating little town with a history that dates back to Julius Caesar and Roman occupation. It has historic homes and villas, and it’s also known as the site of a terrible, terrible murder that helped cement the hatred and suspicion of absinthe. In 1905, absinthe was riding a wave pf popularity among the masses in spite of a lot of hype that was already in full swing. The continued popularity was in part because of its properties, but also because of its rather affordable price. Until, that is, a peasant named Jean Lanfray drank a little too much—not only of absinthe, but of his usual daily allotment of wine and at least three other types of alcohol. He returned home after his binge, got into an argument with his pregnant wife, and killed her along with their two children. He then shot himself in the head, and when police made it to the scene, they found that he had not only survived, but was conscious. The day—August 28—was a turning point in the world’s view of alcohol in general and absinthe in particular. It had long been suspected that there was something dangerous about the green liquid, and with the help of journalists who started calling the crime the “Absinthe Murders,” absinthe was completely condemned. It was banned in Switzerland in 1910, and the United States and France soon followed suit. Ultimately, Lanfray succeeded in his bid to commit suicide: He hanged himself in jail three days after his trial ended.

9Manet And Degas Cause Scandal

Well before the Lanfray murders, absinthe was already something of the drink of bohemian rebels, and when artists Manet and Degas featured absinthe in their works, the reaction was nothing less than outrage. L’Absinthe is one of Degas’s most popular paintings. Even if you’re not an art history major, you probably know which one it is. It shows a woman staring vacantly over her glass of absinthe, a look of overwhelming depression written clearly on her face. When the painting debuted, it was called repulsive, a portrait of degraded souls capable only of vice. The Westminster Gazette went as far as to publish a review saying “Fine painting it may be, but ‘fine art’ is a very different thing.” Manet got a similar reaction to his The Absinthe Drinker. His first major work, he used an alcoholic rag-picker as his model for a piece that didn’t exactly cause the major social splash he’d been hoping for. When he submitted the piece to the French Salon, it was wholeheartedly rejected, and he was faced with the same criticisms that his friends and mentor had given him. He was derided for his choice of subject matter, so much so that when his mentor, Thomas Couture, viewed it, his comments weren’t about the technique or the quality of the piece, but to express his absolute horror that Manet seemed to have “lost [his] moral faculty” to use a subject like the Parisian absinthe drinker. The presence of absinthe themes—whether just the depiction of bottles or the actual drinkers—had a bizarre snowball effect that made people look at what was acceptable for fine art and what wasn’t, no matter how well the painting itself was done.

8A Pirate, A President And An Absinthe Bar

If there’s any place in America that seems a fitting home to absinthe, it’s New Orleans. Throughout the 1800s, the Old Absinthe House was the place to go, famous for their absinthe-and-sugar-water cocktail, called the absinthe frappe (or, alternately, the green monster). And it’s the reason the British lost the Battle of New Orleans. On January 8, 1815, British troops marched on the city. They were ultimately thwarted by an unlikely pair—general and future president Andrew Jackson and the privateer Jean Lafitte. The legend goes that the talks which ultimately cemented the partnership and led to the American victory were held in a secret meeting room in the Old Absinthe House. Lafitte, sometimes called a privateer and sometimes called a pirate, had the ships but no men, while Jackson had men but few ships. In exchange for a full pardon for Lafitte and all his men, the pirate agreed to let the general man his ships with soldiers. It wasn’t long before the British troops fell. Because everything that involves absinthe has to come with some kind of controversy, in 1951, the nearby Maspero’s Exchange filed a lawsuit against the Old Absinthe House. They claimed that they were, in fact, the actual meeting place for the exchange, and if anyone was going to be putting up a plaque, it was going to be them. The district judge dismissed the case with an epic ruling. He stated, “Legend means nothing more than hearsay or a story handed down from the past.”

7Valentin Magnan’s Experiments

The number of claims made against absinthe constitute a long list, and a lot of those came from the work of French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan. He was the one who gave the claims scientific credibility, and suddenly the pitfalls of absinthe were very, very real. In the 1860s, Magnan was already in a highly respected position—he was the physician-in-chief of Saint-Anne, one of France’s most well known insane asylums. Magnan ended up being one of the groundbreaking pioneers in the field of mental pathology. Only 32 years old when he took up residence at Saint-Anne, he was among the leaders in practical laboratory work not only when it came to absinthe, but in other addictive substances like cocaine as well, often using animals to test the effects of various substances and drugs. Even greater than his interest in addictive drugs was his interest in epilepsy; Magnan was key in developing theories on the degradation of nerves and nervous tissues, along with theories on how hereditary and environmental factors act on an individual. He also spoke out in opposition of some of the theories of criminology put forth by Cesare Lombroso. Magnan wasn’t as kind to the idea of alcoholism and absinthe, though. He based his work on the numbers of alcoholics admitted to the insane asylum at Saint-Anne, determining that the number of cases had been on the rise. He also found that there was an increased likelihood of alcoholics to have another in their family. On top of all that, he also pronounced another diagnosis—the steady decline of French culture. He blamed this largely on what he saw around him—alcoholics and the increasing popularity of absinthe. There were more alcoholics, more people diagnosed as insane, and a greater strain on the population at large. He claimed that this was all due in no small part to absinthe, and he set out to prove it. In 1869, he published the damning results of an experiment in which he exposed different animals to a solution of either alcohol or wormwood oil (one of the ingredients in absinthe). The animals who received the alcohol got drunk, while those who got the straight wormwood oil developed seizures. Clearly, absinthe was to blame.

6The Rise Of Absinthism

Despite its obvious flaws, the work of Magnan led to “absinthism” being declared a completely different mental illness than alcoholism. Magnan described absinthism as being characterized by restlessness, confusion, seizures, delirium, and the presence of auditory and visual hallucinations, meaning that the person had consumed so much absinthe that it had resulted in a complete altering of their natural mental state. He also said that the sufferer of absinthism was more prone to irrational, uncontrolled violence and rage, fits of anger, and terrifying episodes of delirium—something that Lanfray would seem to confirm years later. He wasn’t the only one to denounce absinthe, either. The definition of the supposed illness was also published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, the forerunner to the New England Journal of Medicine. There, a student of Magnan’s also added a reddish tint of the urine to the seizures, putting forward the idea that it was a sign of chemicals building up in the body, one of the effects of chronic absinthe consumption. Between 1867 and 1912, 16,532 patients were admitted to the asylum, and about 1 percent of those were diagnosed with absinthism.

5The Ancient Prophecies And Properties Of Wormwood

As if absinthe didn’t have enough going against it, there was also the incredibly ancient—and extraordinarily dark—history and lore of wormwood working against the drink when it came to popularity. Wormwood had been used for medicinal purposes as far back as ancient Egypt, and there are even mentions of it in ancient papyrus documents. A 1552 BC copy of what’s believed to be an even earlier document dating back to somewhere around 3500 BC talks about wormwood in the context that gives it its name: a treatment for intestinal worms. In ancient Greece, wormwood was supposed to be used to help ease labor pains, but the connection between absinthe and wormwood is an odd one. The word “absinthe” is most likely derived from the Greek word apsinthion, which means “undrinkable.” And that, in turn, is a Biblical reference. “Wormwood” is also a star discussed in Revelation 8:10–11. When the end of the world comes, seven trumpets will sound and bring seven horrors onto the world. At the third, Wormwood will crash into the Earth and turn a third of the world’s water supplies bitter, poisonous, and undrinkable, killing off a huge part of the population. The image is a pretty clear one, and even throughout the Middle Ages, medicinal uses of wormwood included purging the system and discouraging babies from the teat when it was time for them to stop breastfeeding.

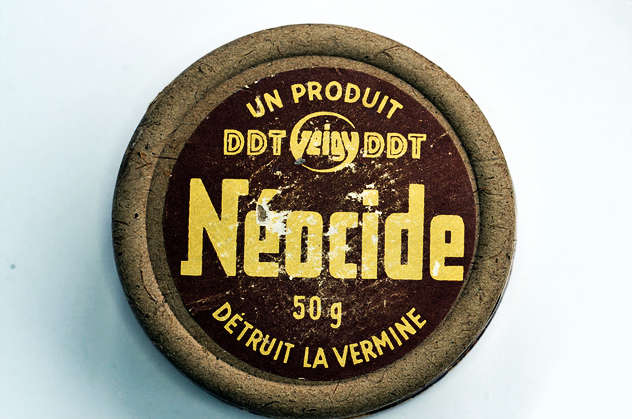

4The Myth Of The Mickey Slim

The myths and fear of absinthe might have started a few centuries ago, but they’ve shown some pretty serious staying power. In the 1940s and 1950s, it was rumored that people weren’t getting enough of a hallucinogenic high now that their absinthe had been taken away, so they decided to make their own cocktail to create the same effects. Addicts are addicts, after all, and absinthe addicts were rumored to be among the worst. The answer was taking gin and mixing it with a little something special. That something? Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane—more conveniently known as DDT. Supposedly, the effects of the gin-and-pesticide cocktail called the Mickey Slim were the same as you’d get from drinking absinthe. And if you look at what we now know the effects of DDT to be—confusion, tremors, nausea, and vomiting—it might seem likely that it could, possibly, pass for an absinthe buzz. The problem comes in trying to find some actual references to it from the mid-20th century. That was about the time we thought DDT was completely harmless, and we were even using it to kill lice. It wasn’t until the 1970s that pest control manufacturers began taking capsules of it with their morning coffee to prove that it really was safe, and the stunt was still being attempted into the 1980s. But just how widespread were Mickey Slims? When you do some digging, there’s not much in the way of supporting evidence that suggests it was anything but an urban legend. Even though the legend says that it was hugely popular, there are few books that actually reference anything about it besides its existence. One is The Dedalus Book of Absinthe, but the trail of sources ends there. There’s also the suggestion that the Mickey Slim was prepared with absinthe instead of DDT, but again, it’s likely one of the urban legends that grew up out of the fear of absinthe and its effects.

3Wilfred Arnold And Van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh was a weird guy. Just what was wrong with him has been debated for a long time, with a rumored 101 possibilities as to just what illnesses he was suffering from. In a paper published only in 2004, University of Kansas Medical Center’s Wilfred Niels Arnold attempted to take another run at diagnosing van Gogh, and part of his theories focus on the consumption of absinthe. Suggesting that its popularity alone was enough evidence that there was something special going on with absinthe, Arnold goes on to suggest that van Gogh’s absinthe habit had quite a lot to do with the downward spiral of his illness. Citing a 1948 study on the effects of thujone, he suggests that an addiction to absinthe and thujone (which is classified as a terpene) explains at least in part why van Gogh began looking for his fix elsewhere—namely, drinking kerosine and turpentine, along with snacking on his paints. He also refers to a pretty fascinating set of theories on van Gogh’s habits put forward by Dutch art historian and van Gogh biographer Jan Hulsker, who completely denied that van Gogh actually drank any absinthe. Even though it’s featured in several of his pieces, Hulsker was adamant that he wasn’t actually drinking the stuff, he was just sort of decorating his surroundings with a glass of it. Arnold comes to the conclusion that it wasn’t absinthe alone that sent van Gogh into his bizarre behavioral states, but he does say that it’s likely he had an abnormal sensitivity to its effects, and it was ultimately responsible for adding to his problems.

2Absinthe And The Downfall Of France

Absinthe was banned in France in 1915, and by that time it had been blamed for a lot—including the deterioration of the quality of France and its people as a whole. By the turn of the century, absinthism wasn’t just a mental illness; it was a rampant disease spreading through the countryside that would ultimately lead to the country’s downfall. By 1910, France was consuming about 36,000,000 liters (9.5 mil gal) of absinthe every year. That was up from only about 700,000 liters (185,000 gal) 35 years prior. According to supporters of the temperance movement and the absinthe ban, absinthe was single-handedly destroying French culture and society. Birthrates were at a low, and illnesses like tuberculosis were at a high. So were admissions into mental institutions and insane asylums, instances of extreme violence, and suicides. While in retrospect it might seem like these are the problems of any country in the middle of a transition into a highly industrialized society, in France, it was all blamed on the absinthe. It was the outbreak of World War I that gave finally the French temperance movement what it needed. When men began enlisting in the French army, they began failing physicals and medical exams at an outstanding rate. With up to 20 percent of people failing to make it into the military, it suddenly became clear that absinthe wasn’t just going to ruin French society, it was going to lose them the war. If the country was going to have any chance in the war, the drink needed to be banned. France was one of the later countries to ban absinthe, as it had already been outlawed in many places from the United States to Italy.

1The Illusion Of Legality

The United States made absinthe officially legal again in 2007, and France only followed in 2011. There’s a bit of irony there, though, as technically, absinthe has been legal in the States for decades. We’re not even entirely sure when absinthe was made legal, but it technically could have happened as far back as the 1930s. The law actually stated that what was illegal was the presence of thujone, the toxic chemical that’s been blamed for most of the absinthe-related problems. The wording of the law, though, says that products containing anything from the Artemisia plant must be thujone-free. Even so, there’s a certain amount of the substance that’s just tolerated. The legal threshold for thujone was 10 parts per million. As long as it was below that level, it was completely legal—most of the legal battles have been over getting manufactures and distillers to understand the guidelines, not actually change them. That brings up the question of just how much thujone is required for “real” absinthe, and whether or not the stuff that’s been legal all this time even qualifies. Absinthe connoisseur and amateur microbiologist Ted Breaux finally managed to solve the long-standing mystery of just how much thujone was present in the old-school, pre-ban bottles of absinthe, and he debunked a lot of the misinformation out there—including the previously mentioned calculations of Wilfred Arnold. Arnold had stated that, based on the ingredients that went into a bottle of absinthe, the thujone content would have been somewhere around 250 parts per million. Enough to be dangerous, sure, but that was also before the distillation process. Breaux had the equipment he needed, and by sacrificing some precious samples of pre-ban absinthe, he found that most early versions of the alcohol didn’t just have less thujone than Arnold projected, but they had way less than the legal threshold—about 5 parts per million. That not only debunks the dangerous nature of absinthe, but it also kind of shows that if you read the small print, it’s amazing what’s actually legal. Read More: Twitter