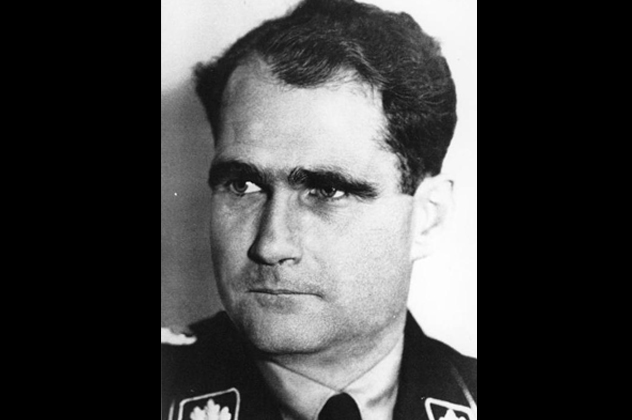

10Rudolf Hess’s Brain Poison

Douglas Kelley wrote that one of the things that surprised him most about former Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess was his absolute naivete. By the time the psychiatrist examined him, he had been in custody for about four years following his attempt to get the British to join the Germans in fighting the Soviet Union. He seemed earnestly shocked that he was taken prisoner and revealed that he was absolutely convinced that he was slowly being poisoned. So Hess began saving food, medicine . . . anything that he was offered, wrapping samples in little brown packages, sealing them with wax, and stockpiling them for later analysis. When first taken captive, he refused all food. After holding out for a whole day, though, he gave in and accepted some milk. Already suspicious, he would only eat with those who were holding him, but when he got a massive headache afterward, he wrote that it was then that he knew he was being poisoned. He also wrote that his captors were apparently disappointed when he answered their questions, so he started pretending simply not to remember. He did it so much that eventually, he says, the amnesia was real, and most likely helped along by what he called the “brain poison.” His certainty that he was being poisoned increased as his captivity dragged on. He thought that there were bones and splinters in his food and powders in his laundry to cause rashes. He claimed that the skin on the inside of his mouth was being worn away and claimed that his stomach pains were so bad that he needed to scrape and eat lime from the walls of his cell relieve the pain. Brain poison was destroying his memory more and more, and kept on believing it even though a Swiss messenger tested his food and told him that there was nothing wrong with it.

9The Farmer And The Women

Part of the evaluation program included showing the subjects pictures and asking them to tell a story about them. Officially, this is called the Thematic Apperception Test, or TAT, but it’s also known as the picture interpretation technique. The subject is asked to look at the picture and explain what happened just before the events in the picture, what’s happening in the picture, the thoughts and feelings of the people, and what happens afterward. Developed in the 1930s, the idea is that underlying personality issues will come through in the telling. When shown a picture of a man working in a field with one woman watching and another walking away, Hermann Goering told a story of a farmer “deeply devoted to his work and a lover of nature” who was trapped between two women. The one watching was a simple country girl, his wife, while the other was a younger, more intelligent woman who was everything he wanted but wouldn’t have. She was leaving him, bound for the city and a life of her own. Other Nazis told some pretty revealing stories, too. Alfred Rosenberg (pictured above), whose writings were often lofty and pontificated on philosophy and racism, was determined to be pretty lazy when it came to imagination. Given a picture of man climbing a rope, he made the figure an acrobat who couldn’t do the difficult acrobatics he’d planned, so he simply climbed down. Rudolf Hess, in the meantime, refused to play. No matter how much Kelley tried to get him to tell a story, he insisted that he was much, much too tired and couldn’t come up with anything.

8Robert Ley’s Brain

Robert Ley was the head of the German Labor Front for more than a decade throughout the war years. He was the one responsible for organizing and directing the lives of the Third Reich’s everyday citizens, and his brain ended up divided into cross-sections and prepared as slides. All together, there were 22 men whom Kelley examined, but Robert Ley was perhaps the oddest of the lot. Results of his tests made the doctor suspect that he had suffered some kind of frontal lobe damage in spite of a clean bill of health. Ley had regular, angry outbursts, he got names of colors confused, and his speech was difficult to follow, irrational, and often just didn’t make any sense. While Kelley suspected that the others were suffering from some sort of psychological disorder, he was pretty sure Ley’s was a physical one. When Ley committed suicide in this cell in 1945, Kelley wrote that the man had done him a favor by giving him access to his brain. Off the record, Kelley had a colleague prepare the slides, which he then smuggled out of the country and back to the US. A neuropathologist at the Army Institute of Pathology in Washington, DC, first confirmed that there were signs of a degenerative disease in Ley’s brain. A few years later, he got around to asking for a second opinion. This time, results came back saying that the brain wasn’t as abnormal as the first diagnosis had suggested. This scientist said that while there might be something there, there might not be, either. By that time, though, Kelley was well beyond doing anything about it, and the slides were buried in the rest of the documentation from his work.

7Goering’s Paracodeine Addiction

When Hermann Goering was taken into custody, what he brought with him alone spoke volumes about his self-importance. There were 12 monogrammed suitcases, jewel-studded medals, the equivalent of about $1 million in cash, several cigar cutters, and a stash of watches and cigarette cases. Along with potassium cyanide capsules sewn into his clothes and stashed in a can of coffee, there was also a suitcase filled with enough paracodeine for a small country. The case was filled with somewhere around 20,000 capsules, and it’s thought that he had gone directly to Germany’s manufacturers for his stash. That wasn’t all of it, either—he admitted that he had already flushed a large amount of pills before his capture, as he’d thought that it would have been unseemly to have been captured with as many pills as he’d had. Originally, he claimed that they were part of a doctor’s prescription that he was taking for a heart condition, insisting that he was required to take 40 pills a day. Not surprisingly, they didn’t believe him and had the pills tested. The painkiller, related to morphine and opium, was found to work along the same lines as codeine, but with a stronger sedative action. They started weaning him off the pills immediately, dropping his daily dose to first 38 pills, then to 18. At that point, medical staff were advised not to reduce the dose any further, since they weren’t sure what would happen to him if he was taken off the drugs completely. He was still going through withdrawals by the time Kelley took over his treatment.

6Nazi IQ

Part of establishing whether or not the Nazis were capable of standing trial was the administration of an IQ test. The Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Test was adapted from English and given in German, and at the time, it was one of the most widely used IQ tests available. Scores of 65 or less were classified as “defective,” between 80 and 119 as normal, and 128 and above was “very superior.” Only about 2.2 percent of the population scored in that range. Some of the questions were altered to get rid of any kind of cultural bias, and the test measured things like memory, mental calculations, picking out objects or details deleted from a picture, and even hand speed. The average for the 21 Nazis tested was 128. (Ley was already dead by this time.) The highest score was 143, from Hjalmar Schacht, with Goering, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Karl Donitz, Franz von Papen, Erich Raeder, Hans Frank, Hans Fritsche, and Baldur von Schirach all testing 130 or above, and with Joachim von Ribbentrop, Wilhelm Keitel, and Albert Speer all also falling into the “very superior” category. Their reaction to IQ testing was even more fascinating, with many of them actually looking forward to the testing and most being pleased with the results. Even those like Franz von Papen, who were initially irritated with the idea that they needed to subject themselves to a test that was so far beneath them, admitted that it was one of the more enjoyable moments of their captivity. Perhaps most bizarre was the reaction of Wilhelm Keitel (pictured above) to the test. He was very, very impressed by it, even going as far as to say that it was much better than the “silly nonsense that German psychologists resorted to.” Later, Kelley discovered that Keitel had outlawed all intelligence testing after his son had flunked out during the tests to enter officer training.

5The Rorschach Tests

The psychologists also gave the Nazis Rorschach tests, hoping to uncover anything the prisoners might be trying to hide in their personalities. The tests were given by Dr. Gustave Gilbert, Nuremberg’s prison psychologist, about three weeks into their evaluation. Among the most notable are the test results for, again, Hermann Goering. Even to those going back through the results today, they stand out as being imaginative, the results of a natural storyteller. But as exceptionally imaginative as his responses might have been, there was little to no difference between the responses of the men of the Third Reich and ordinary American citizens. When Kelley and Gilbert released their findings, a psychologist named Molly Harrower tried to have the Nazi Rorschach results reviewed by a panel of independent experts. Everyone she contacted refused. It wasn’t until 30 years later that Harrower could set up an objective experiment to evaluate the findings. In a double-blind study, she took the results from the Nazi officers, a group of clergy members, and a group of hospital patients. After all the groups were analyzed, it was concluded that there was no difference in the responses. In 1989, another comparison was done between eight of the war criminals (those who had received a death sentence) and a random group of 600 other subjects. This comparison had a slightly different verdict, showing a likelihood of schizophrenia in Hess and the presence of what was deemed a distorted reality in others.

4Howard Triest’s Confrontation With Evil

Kelley and Gilbert interviewed Nazi war criminals again and again, looking at their responses through the lens of mental health. But there was another man there, too—Howard Triest, who was tasked with reading and censoring German mail and assisting with interviews and translations when necessary. His point of view was radically different. A German-born Jew, Triest had been Hans Heinz Triest when he and his family had been living in Munich. When things started going sideways, he had been sent to America ahead of his family. The rest of his family hadn’t been as fortunate; his sister, Margot, found refuge with the Children’s Aid Society, but his parents would die at Nazi hands. Margot’s last communication with her mother was a postcard which her mother threw from the train that was taking her to the death camps. Miraculously, Margot received it. Triest ended up making it to safety in America, where he lived with an uncle until returning to fight on the side of the Allies. Recruited as a translator, he had been on the verge of being sent back to the US when he was assigned to Nuremberg and suddenly found himself sitting in on interviews with the men who had ordered the deaths of his family. He remembers Streicher in particular, who befriended him and was supposedly impressed with Triest’s clearly Aryan features. Streicher professed that while he could smell a Jew from a mile away, Triest obviously was of good Nordic stock. He remembers Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess, too, for being so proud that he had killed three million people instead of the required two million. Triest’s story provides a radically different look into the psychology of the Nuremberg trials—that of the survivors. When asked how he didn’t kill those who’d killed his family when he had the chance, he responded that it was enough to stand in front of them, knowing that they had lost. His story touches the German everyman, too; Triest worked through the de-Nazification of Germany and spoke openly of both the collective amnesia that seemed to have passed over the country’s citizens and of people who showed him pictures and letters written from their Jewish acquaintances to show that they weren’t a part of the Final Solution. At the same time, he said that de-Nazification was pointless, because nobody could find any more Nazis anyway.

3The Nazi Personality

Part of the psychiatrists’ jobs was to determine whether or not the 22 Nazi war criminals were fit to stand trial, but they also wanted to know just why they had visited such atrocities on the human race. In the end, they were all deemed to be legally sane and fit for trial, but just what drove them to do what they did . . . that was harder to pin down. According to Kelley, he believed that the development of people and personalities that could commit such horrible acts was the result of a “socio-cultural disease.” Gilbert, on the other hand, thought that they had all been so programmed to obey orders that any of their individual intelligences or personalities were overridden by their blind devotion. In the end, no one—even today—has been able to interpret any of their findings or data in such a way that isolates the so-called Nazi personality. They didn’t show signs of being abnormally violent or overly emotional, and many held bizarrely normal family lives outside of their day jobs. Even Rudolf Hoess—the commandant of Auschwitz—who didn’t have the luxury of claiming that he wasn’t intimately involved with the death that was happening on a daily basis, responded to his postwar questioning with a bizarre indifference. Hoess responded that he simply thought he was doing all the right things and obeying orders, and when asked if he was haunted by the memories of those who died at his order or if he had nightmares about the death chambers and the bodies, his only answer was, “No, I have no such fantasies.” There was also no pattern even in the last moments of those who were executed. Hans Frank asked for God to be merciful and was grateful that he had been treated so well in prison. Ribbentrop asked for German unity and peace. Writer and philosopher Alfred Rosenberg simply denied the chance to speak. Streicher shouted, “Heil Hitler,” and Kaltenbrunner professed love for his country and regret that Germany had not been led by the soldiers. Even at their executions, there was no common thread.

2The Consequences

The findings that there was no Nazi personality and the discovery of just how normal these men were was a terrifying one. The results of the IQ tests that showed they all had above-average intelligence was so seemingly unthinkable that at first, the Americans refused to release the information. Later, Hanna Arendt would coin the phrase “the banality of evil” to illustrate an evil that wasn’t born out of malicious desire, delight in murder and death, or even overwhelming hatred, but that was born of something much, much more boring—the unthinking normalcy of doing what the boss says. Kelley was hoping to find a certain set of red flags in mental health, personality, and psychology that would alert others to the potential for committing atrocities in the future and would allow someone to put an end to them before they happened. Not being able to find any such personality markers was understandably devastating, and the consequences were pretty bleak. Eventually, he would give up on psychology altogether and shift the focus of his professional work to criminology. He wrote, “I am quite certain that there are people even in America who would willingly climb over the corpses of half of the American public if they could gain control of the other half.”

1Douglas Kelley’s Suicide

Just before he was due to be executed, Hermann Goering committed suicide by cyanide. His note indicated that he was fine with being shot, but he did not approve of his sentence to be hanged. That was in 1946, and bizarrely, the consequences of that were felt on New Year’s Day, 1958, half the world away. Kelley, now 45, was cooking dinner for his wife, father, and three kids. Kelley burned himself, and according to his son, Doug, the next thing he remembered was shouting. Moments later, Kelley was on the stairs, foaming at the mouth, the remnants of a vial of white powder in his hand. Until that moment, everything had seemed normal. They had gone to a New Year’s Eve party, they had just bought a new color television, and Kelley had just picked up his father, bringing him home so they could all watch the Rose Bowl. But the darkness was there, too, and Doug remembered a man who was secretly alcoholic, who had contemplated suicide before, and who was regularly angry. The incident left scars on the family, too. Kelley’s son was married four times and spent a decade wandering across the globe, and his wife just doesn’t want to remember the tragedy. It was only recently that the contents of his boxes, taken home from Nuremberg and stored all these years, were given to Jack El-Hai to go through in order to make some sort of sense out of them and to hopefully compile a book. It hasn’t given any answers to the family that was left wondering why he committed suicide in a way so eerily reminiscent of Hermann Goering, to whom he was so close. In Kelley’s book, he commends Goering for taking his life in a way that left his fate in his own hands. It’s a disturbing epilogue to one of the most infamous trials in history, and one that left more questions than answers. Read More: Twitter