10Kukri

The kukri is the symbol of the Nepalese nation, as well as the Gurkha regiments that made it famous. Relying on their famed knives for close-quarters combat, Nepalese fighters, the Gurkha, allied with the British to maintain control over India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The Gurkhas’ fighting prowess gained them a reputation as fearsome soldiers, and their support of England landed them their own regiments within the British forces. The Gurkhas and their knives became so well known that the British used posters of them sharpening their kukris as propaganda to instill fear in Argentine conscript soldiers during the Falklands conflict. The kukri itself is usually from 40–46 centimeters (16–18 in) long. Much like a machete, it’s a chopping weapon. Originally used by Himalayan farmers, it evolved from a simple farming tool and is still used as a utility knife as well as a weapon. One interesting feature is the notch near the grip that directs blood away so that it can’t wet the handle. It’s said this aspect is symbolic, as larger, sword-like kukris are used in ceremonies to behead animals and bring good fortune to a village. If the head comes off in one stroke, it means luck. But kukris are first and foremost fighting weapons. Even now, they are standard-issue equipment among the Gurkhas, who will keep wearing them even after retirement. One such retiree fought off 40 train robbers with only his kukri. Bishnu Shrestha had recently retired from the Gurkhas when a band of 40 robbers assaulted a train he was riding on. He sat silently as the bandits stole passengers’ valuables, but when they tried to steal the virginity of the 18-year-old passenger beside him, the retired soldier took out his kukri and began single-handedly eliminating them. Shrestha killed three and injured eight others. The rest fled, wanting nothing more to do with the fearsome ex-soldier. For his bravery, Shrestha was brought out of retirement so he could receive a promotion and a reward of 50,000 Indian rupees. He also received a bounty for the robbers and discounts on train tickets for the rest of his life. Given his skill at dispatching robbers and protecting the innocence of virgins, we’re sure any train company would be glad to have Shrestha onboard.

9Parrying Dagger

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the introduction of firearms made heavy armor impractical. Lighter swords like rapiers came into vogue to replace the larger weapons of knights. Shields also became impractical and were forsaken by European duelers for parrying daggers. A skilled fighter could used his dagger just as effectively as a shield to deflect blows from slimmer rapiers. The lack of heavy armor also meant that a dagger was just as deadly as a sword. Thus, unlike shields, the daggers were also handy weapons. As parrying daggers grew in popularity, both the combat systems that used them and the daggers themselves grew more complex. There were countless varieties of parrying daggers, but all were designed to momentarily trap an opponent’s sword and give fighters a precious, unguarded second to strike. Of course, the daggers also had to protect the warrior’s hand while doing so. To this end, many parrying daggers had elaborate guards to stop incoming blows. The matter of stopping an opponent’s blade, however, produced a few general kinds of weapons. “Sword breakers” had teeth along the blade to trap and perhaps even break the opponent’s sword. Another kind was the trident dagger, which had a spring-loaded mechanism that split the blade into three sections with the push of a button.

8Jambiya

Jambiyas are wide, double-edged knives worn as a symbol of social class and manhood in Yemen. It’s been said that men would rather die than be seen in public without them. In the area of Tihama, boys were presented with their first jambiyas after going through a ritual circumcision in their mid-teens. Jambiyas are often elaborately decorated, even with gold. Islam, Yemen’s dominant religion, forbids men from wearing gold jewelry, but Yemeni men consider jambiyas weapons, and thus an exception to the rule. Yet the most prized material for handles is not any precious metal, but rhinoceros horns. The demand for such handles is contributing to rhino poaching. One report says Yemen imports 1,500 rhino horns each year for its jambiyas. Likewise, after craftsmen make the handles, they export the shavings and powder to Asian countries, where they are used in alternative medicine. Rhino horn shavings are big business in Yemen, where 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of unprocessed horn powder is worth as much as $1,000. Although jambiyas are now mostly for show, prior to the early ’60s they were still being used as weapons. Yemini fighters held their knives downward and aimed for the base of the neck, where a well-aimed blow could split open an opponent’s chest wall. Their only practical purpose nowadays seems to be oath-taking. When two men swear an oath, the daggers are unsheathed and put through an elaborate set of motions to seal the promise.

7Sai

Although often associated with Japanese martial arts, the sai is believed to have been created during the Ming dynasty and brought to Okinawa from China. Somewhat like a stiletto, it is a stabbing weapon that generally doesn’t have a cutting edge. The length of a sai is either round or hexagonal, and, if sharpened at all, will only be tapered at the tip. They were much like the parrying daggers of Europe—their pronged shape lent itself to deflecting blows. They were seen as useful against Japanese swords, like katanas. Since sais were generally wielded in pairs, a practitioner of saijutsu could trap an opponent’s sword within the prongs of one, then strike with the other. When Okinawa fell under oppressive rule from the Japanese government, metal tools and weapons were outlawed without special permission. Saijutsu was passed on in secret until the ban was lifted. It was later taken up by law enforcement. Even today, traditional practice of saijutsu is carried out with little to no noise, and banging the weapons against each other is prohibited.

6Mark 1 M1918 Trench Knife

Trench knives saw widespread use during the First and Second World Wars. Germans relied on the Nahkampfmesser fighting knife for close-quarters combat, while British forces used their own type of knives. The US military produced several trench knives, but these saw limited use. The Mark 1 M1918 had a flat, double-sided blade with a brass or bronze handle that incorporated a spiked knuckleduster. The knuckleduster’s grip guard, while usable as a weapon, simultaneously aided the soldier’s grip. At the bottom of the pommel was a large nut used as a kind of skull hammer, which gave the Mark 1 three possible modes of attack. The guard prevented it from becoming a popular weapon. The knives arrived late in the war and were only issued to soldiers whose gear did not include a bayonet, such as paratroopers. These soldiers often needed utility knives, however, and the trench knives were designed for combat. Many soldiers hated them. Due to the weapon’s shortcomings, as well as a shortage of brass required to produce it, Mark 1 didn’t see restandardization in World War II. However, some were ordered and issued to soldiers for lack of a better alternative.

5Kris

Kris, or Keris, are Javanese daggers seen as both weapons and spiritual objects. They were believed to have magical powers. A number of ancient kris were forged from the astral iron of a meteorite that fell roughly 200 years ago near the temples of Prambanan. They, and what remained of the meteorite their metal came from, were considered sacred objects. Strongly linked to Indonesian culture, almost every part of this symbolic weapon is pregnant with meaning. The wavy, almost slithering shape of the blade is associated with the snake-like naga from mythology. Even the pattern inside the steel itself was believed to act as a talisman. Some kris were forged using several kinds of steel with varying carbon content. Mixing steel in this fashion is called pattern-welding and creates an effect similar in appearance to the famed Damascus blades. Pattern-welding is a different process, however, and while kris forged by this method retain a similar appearance to the Damascene weapons, they are quite different in chemical composition. The varying patterns smiths could create in the steel were believed to ward off bad fortune and protect the well-being of the weapon’s owner.

4Misericorde

Widely used in the 14th century by French knights, misericorde were large but thin stiletto-type daggers easily slipped through the joints in plate armor. Misericorde were almost useless in combat, since many of them didn’t even have guards. Never intended to be used in battle, they were at best used as a last resort. The misericorde derived its name from the Latin word roughly meaning “act of mercy.” Its main purpose was to end the suffering of a fallen opponent. If a knight was knocked off his horse or seriously wounded, ancient French knights would use the misericorde to deliver the death stroke. This was not viewed as heartless killing but a mercy stroke to a man wracked by pain during his last moments. Still, for some fighters less inclined to acts of mercy, misericorde could be used to threaten a seriously wounded knight into surrendering. The victor could later collect a ransom should his opponent end up surviving his wounds.

3Turkana Wrist Knife

Wrist knives are used by the Turkana people of Africa. Those Turkana who follow the indigenous religion believe that all domesticated animals, such as cows, are theirs by divine right. Many other nearby tribes believe the very same thing, which has led to an endless cycle of cattle raids and border conflicts. The Turkana people in particular carried out a continuous campaign to expand their territory. As such, they valued martial prowess, and men carried an abundance of weapons including spears, shields, finger knives, and wrist knives. Wrist knives were generally fashioned out of steel or iron beaten into shape by a rock, though hammers became more common after the technology reached the Turkana. Among the Turkana, the knives were generally worn on the right hand by men, although they were also common among other nearby tribes and worn by both sexes. While the wrist knives were weapons of war, they had a number of other uses. They were readily available to cut food but also served to settle differences within the tribe. Since it was forbidden to kill another Turkana with a spear, wrist knives were used to deal with internal disputes that ended in violence.

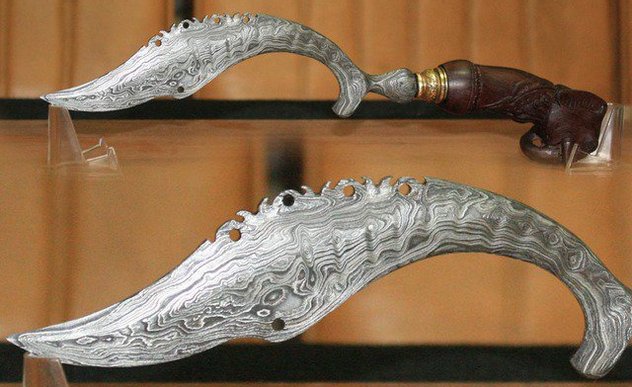

2Kujang

One of the most fascinating daggers of Java is the kujang, a sickle-shaped dagger believed to uphold the balance of the world. Once popular with Javanese kings, the kujang‘s distinctly shaped blade was believed to have been inspired by a divine message proclaiming their sovereignty. Unlike many blades, the shape of the kujang did not come from any advance in weapons technology. The unique knife was created after a vision of a Javanese king. The original kujang was a farming tool, but a king named Kudo Lalean claimed he saw a weapon that symbolized the united Java island in a prophetic vision. After the dream, he had his best blacksmith craft the mystical blade. The result was a weapon in the shape of the island, which had three holes to symbolize the three main deities of the Hindu religion. The weapon later underwent some modification, after Islam became the region’s dominant religion. It was redesigned to look like the letter “Syin,” the first of an important verse in the Quran. The three holes were also changed to five to represent the five pillars of Islam.

1Kila

Kilas are ritual daggers first created in ancient India, although they later found popularity in Tibet, where they are called phurba. Nearly every part of the dagger is ripe with symbolism. The daggers themselves symbolize the Buddhist incarnation of the wrathful deity Vajrakilaya, whose three faces are often depicted near the end of the handle. Grips vary in design and depict a range of divine creatures. The three-edge blade represents the severing of ignorance, greed, and aggression. Kilas were sacred objects, so they were not used as weapons. With some being made of wood, they were not much use against the Tibetan shaman’s fellow man. They were, however, believed to be the ultimate weapon against the supernatural. Due to the association with Vajrakilaya, who was believed to eliminate obstructions, kilas were tools for exorcising demons and malevolent spirits. The shaman would stab the kila into a bowl of rice in front of an ailing patient. This would bind the spirit or sickness while the shaman chanted sutras to dispel it. One of the most famous figures in the Kila cult was said to have used them to rid Tibet of its “pre-Buddhist demons.” Nathan keeps a Japan blog where he writes about the sights, expat life, and finds Japanese culture in everyday items. You can also find him on Facebook and Twitter.