To date there is no suitable, long term, synthetic replacement for whole human blood, making donations of whole blood or platelets (apheresis) a necessity. Administered in the proper setting the procedure is very quick, taking only 10 minutes or so, but as pre-screening of each donor is required, the entire process usually takes about an hour. In the U.S., blood products are administered on the average of 38,000 units daily, and the need is expected to increase by about 6% annually, with larger demands in cases of war or disaster. Blood has a limited shelf life. The different components of blood, (whole blood, red blood cells, platelets and plasma) can last from 5 days to a year or more. Interesting sidenote: Blood acquired in the U.S. from PAID donors cannot by law be used for the purposes of transfusion. Chances are, if you have been paid for a blood harvest, it was used by the pharmaceutical industry for the production of medications.

Nobody can benefit from the gift of life until permissions and releases are legally tendered. These legalities are different from country to country. In the U.S. it is considered customary for a person to verify that they wish to participate (or consent) to organ sharing, often with a DONOR sticker on the back of their driver’s license, or by preparing a “living will”. In other words, we must let someone know that we wish to share. But the norm throughout most of the world relies upon dissent , a legal understanding stating that unless an individual during their lifetime specifically denied permission to harvest, they are considered an active participant in organ acquisition. This is the norm in Spain, and some believe it is why that country is proven to be the most generous in regards to donor ratio–34 donors/million population. The U.S. comes in at the median with 26 donors/million, and Austria comes in very low at 10 donors/million.

Kidneys, heart, liver, pancreas, lungs, and intestines—These are the primary organs that most of us think of when the subject of organ donation is brought up. And rightly so, these are the organs that represent the greatest need in the waiting lists around the world. These organs must be transplanted within hours, there is no way to store these organs for viable use later. Not so, when it come to tissue donation. According to OrganDonor.gov “Corneas, the middle ear, skin, heart valves, bone, veins, cartilage, tendons, and ligaments can be stored in tissue banks and used to restore sight, cover burns, repair hearts, replace veins, and mend damaged connective tissue and cartilage in recipients.” With the proper preparation and foresight, one death can help over 50 others to begin their return to health.

Two simple words, yet when used together, they seem to garner a hailstorm of controversy. A huge portion of research is being devoted to these microscopic building blocks of life, and the major contributions they can add to the medical field’s repertoire. Medical researchers anticipate stem cells to play an important role in the future treatment of stroke, diabetes, spinal cord injury, blindness, deafness, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis and cancer. Contrary to common belief, primary harvest of stem cells does not occur from fetal tissue, but from other sources like the blood in umbilical cords. Stem cells can be harvested from whole blood by being coaxed from bone marrow through daily injections of a drug called Filgrastim. Bone marrow transplants themselves are a stem cell transplant, yet many people who oppose stem cell research support this type of therapy in the treatment of leukemia and other conditions. Healthy adults between the ages of 18-60 can donate blood stem cells, and there are organizations world wide devoted solely to the screening and matching of such donations.

Not all donations of life giving proportions come from the dead. Easily recognized in this catagory are donations of blood, bone marrow and blood stem cells. Most of us know that we have two kidneys and can easily survive if we give up one of them. Not so many people know that you can give one or two lobes of your liver, and this miraculous organ will regenerate itself to almost full size in both the donor and recipient in a very short time. A donor can give a whole, or part of a lung, part of their pancreas or part of their intestines, and although these will not regenerate in either patient, they are fully functioning. And many a parent has given thanks to those who chose to donate their sperm or ova, one of the few types of live donation where monetary compensation for the donor is not generally considered out of line or immoral. Interesting sidenote: From OrganDonor.gov– “Surprisingly, it is also possible for a living person to donate a heart, but only if he or she is receiving a replacement heart. This occurs only when it is determined that someone with severe lung disease and a normally functioning heart would have a greater chance of survival if he or she received a combined heart and lung transplant. As a result, the heart-lung recipient’s own heart, if it’s in good condition, is then donated to an individual who needs only a heart transplant.” Currently there are 82 heart/lung recipients on the U.S. waiting list.

In our modern and brave new world we are all coming to recognize that “all men are created equal”, but in the field of organ donation this is not always the case. Sadly, when it comes to the matter of disease and related organ failure, ethnicity plays a role in the statistics. According to the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services–“Native Americans are four times more likely than Whites to suffer from diabetes. African Americans, Asian and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics are three times more likely than Whites to suffer from kidney disease. Many African Americans have high blood pressure (hypertension) which can lead to kidney failure.” Because of these facts, ethnicity becomes one of the criteria when matching potential donors to recipients, as an ethnic match often times becomes key in the ultimate healing process and helps alleviate rejection problems. Yet oftentimes, cultural beliefs and religious restrictions make it hard for members of minorities to choose to become donors, to the detriment to those others who are fighting a life threatening illness.

Although society as a whole recognizes suicide as a selfish and misguided solution to one’s problems, sometimes there is an unforeseen benefit from this final act. In the cases where brain death has occurred during suicide, (about 3.8%), these troubled souls have made themselves potential donors. Their families grant donation rights more often in these cases, rather than in other causes of death, but research on the subject has not revealed exactly why. The majority of these cases occur in young men with an average age of 26, with relatively healthy organs. On the other hand, legislature is currently being rewritten to try to discourage those who have a desire to give the ultimate gift to others through the act of suicide. One example of this type of suicide based donation was brought into the limelight in the recent movie, Seven Pounds, starring Will Smith. (It was this movie that inspired my research and subsequently, this list.)

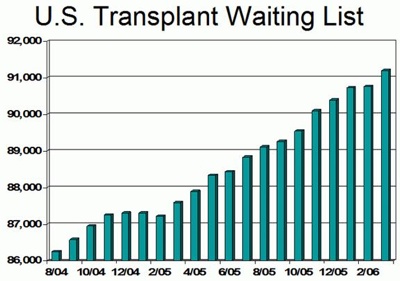

We’ve all had to wait in a line at one time or another, sometimes trying our patience to the breaking point. But no line at the supermarket or post office could be as stressful or deadly as the waiting lists for transplant. At the website United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a tally of people awaiting their surgery is updated daily. As of the writing of this list the number was 104,945, with 80% of that number being those in need of kidneys. Since need far outweighs supply, waiting times can be long, from an average of three weeks for a heart to 476 days for a kidney. Lung replacement has the longest waiting time dependent upon whether one lung or two is needed. The average wait for a lung can be as long as 1068 days, just a few days shy of three years. Although the U.S. averages about 74 transplants daily, about 17 people die each day, waiting.

No lives could be saved by any of these gifts until the scientific community examined the mysteries of rejection. Since the discovery of blood groups by Professor Karl Landsteiner in 1900 scientists have continued to make monumental strides in the understanding of the human immune system. Transplant rejection has come to be recognized as the body’s attempt to repel foreign tissue, much the same way it would attack an unwelcome virus or bacteria. But since an organ is not an unwanted invader, steps are taken to insure compatibility. Before organ donation proceeds, potential organ donors are rigorously screened on a case by case basis to ensure that risks of infection, disease, complications or donated organs being in a sub-optimal state are minimized or eliminated. Hyper acute rejection, usually the result of mismatched blood type, will occur within minutes of the surgery and the only solution is the removal of the organ. Acute rejection often occurs within one week to three months of the surgery, and is usually treated with a short course of strong corticosteroids that suppress the immune system. A bone marrow transplant can also decrease rejection, but only if the marrow comes from the same donor as the transplanted organ. Chronic rejection is a longterm failure of the organ, it is irreversible and cannot be treated effectively.

We watch in dread and horror, at movies like “Turistas” and TV shows that are more and more often featuring black market organ harvesting as part of their plotline. But these scary scenarios are only reflecting a new, gory trend that is becoming increasingly common due to the high demand for transplantable organs. The term for this trend in locating and acquiring an organ is being coined “organ tourism”, “transplant tourism” and “organlegging”. (Like bootlegging, but for organs.) Prevalent in under-developed countries, selling off “extra” organs for many may be the only way to earn an income in overcrowded, economically backward regions. Unfortunately these backdoor surgeries are often performed in unhygienic conditions, with improper, non-sterile equipment, and after care is focused upon getting the excised organ to it’s new owner, not on the recovery of the patient. If a “donor” does survive their procedure, they are often stiffed on the cheap payment ($500- $5000) they were promised. Legislature to establish policy on the right of the individual to sell their organs is an ongoing battle and can only be established on a country by country basis. Advocates of a policy of payment, argue that legal monetary compensation will compel more people to donate. But those opposed, fear that paying donors for their organs will make transplantation available only to the wealthy. Regardless, the trade in organs continues and there will be no way to regulate the safety of everybody involved until these legal and moral questions can be resolved.