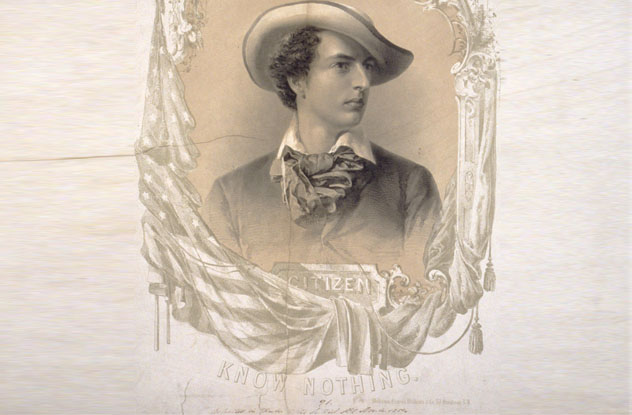

10The Know-Nothing Party

America has a strange, double-sided opinion of its origins. While it proudly proclaims itself to be a diverse melting pot of different cultures, it also can be extremely suspicious of outsiders. One product of this prejudice was the anti-immigration Know-Nothing Party, so called because members, when asked about its secret operations, would say they knew nothing. It wasn’t just a small, upstart political party that died out quickly, either; the Know-Nothing party had major footholds in northern state governments like Delaware and Massachusetts, counting mayors, governors, and other city officials among its ranks. In 1856, former president Millard Fillmore even made another run at the White House on the Know-Nothing party ticket. Ironically, the party’s downfall came when they tried to extend their reach into the slave-owning South. The Know-Nothings might have wanted to purify America and eliminate immigrants, but they were also anti-slavery. After finding out about these irreconcilable differences, the party dissolved; many members joined another political party—the Republican Party.

9FDR’s Proposed Second Bill Of Rights

In 1944, Franklin Delano Roosevelt thought the United States government was in need of a bit of an overhaul. He knew few who served alongside him would support his new vision for the country, so he pitched his idea for a second bill of rights to the American public during his 1944 State of the Union address. Unlike the Bill of Rights, which ensured citizens’ freedom by limiting government action, FDR’s second bill of rights called for greater government action for social and economic stability. He called for a formalized right to education, freedom from economic ruin, access to health care, a decent home, and the right to a living wage. For business owners, he called for a guarantee that all businesses could operate without infringement from monopolies and that farmers would receive a government-backed price for crops and livestock. FDR said an average standard of living didn’t matter. If any part of the population, no matter how small, was hungry, uneducated, and suffering, then the government had failed. “Necessitous men are not free men. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

8The First Assassination Attempt On Lincoln

After Abraham Lincoln’s November 1860 election, not everyone was happy with the nation’s new president. Death threats started pouring in almost immediately, and though Lincoln brushed them off, they presented major problems for his small staff. Just before his inauguration, rumors said that opponents of Lincoln planned to kill him as he rode to Washington. Railroad magnate Samuel Morse Felton got wind of these rumors and contacted Allan Pinkerton, Chicago’s first private detective. Pinkerton knew the plot’s keystone had to be Baltimore, as it was one of few cities through which Lincoln absolutely had to pass. Pinkerton disguised himself as a stockbroker, rented some offices, and started making the rounds through the volatile Baltimore business world. Pinkerton and his handful of associates soon ran into Italian immigrant Cypriano Ferrandini, who supported his own country’s rebellions and wanted Lincoln dead before Inauguration Day. A $25 donation to the cause got Pinkerton, in his stockbroker guise, a meeting with the would-be assassin. Realizing the threat was very real, the detectives pushed further until finally being initiated into the underground movement. Ballots were drawn, and eight of the rebels were tasked with killing Lincoln. Pinkerton retreated from Baltimore, armed with the news and an insistence that Lincoln’s itinerary through Baltimore be changed. The president-elect secretly advanced his schedule. Hidden from view, attention drawn from him by distractions, and at one point traveling as a female detective’s “invalid brother,” Lincoln arrived in Baltimore earlier than expected. By the time the plotters realized that Lincoln had slipped through their net, Pinkerton and his associates had already gotten the man who would be one of the country’s greatest presidents safely to Washington for his inauguration.

7The Anti-Masonic Party

Many politicians and business owners—America’s movers and shakers—are Freemasons, but if this 1820s political movement succeeded, the dynamic would be very different. In 1826, the disappearance of William Morgan sparked a tirade of anti-Masonic sentiment. Morgan had threatened to expose the Masons’ secrets after being rejected for membership, and since his disappearance was never solved, many assume the Masons killed him and covered it up. The public also began believing it was dangerous for so many men in positions of power to belong to a secret society. The Anti-Masonic party started out as a religious movement to abolish Freemasonry. It quickly expanded into a political platform that claimed that Masons used political power for personal gains against national interests. Some Masons even switched sides; the Anti-Masons’ nominee for the 1832 presidential race was former Mason William Wirt. The party wasn’t just a passing fad, either. The Anti-Masonic party did some serious damage to the organization, and the aftereffects still echo today. The number of Freemasons in the country dropped by 60 percent, and almost 400 lodges closed in New York State alone. After the Anti-Masonic movement, Masons were often relegated to having the same sort of stigma that followed other groups like labor unions. Had the movement succeeded fully, our list of presidents might have looked rather different and not included names like Harry S. Truman, Theodore Roosevelt, William McKinley, and FDR.

6The Republic Of Cascadia

When Thomas Jefferson sent famed explorers Lewis and Clark to chart the United States, he may not have been seeking new land to annex into the country. Instead, Jefferson envisioned a completely independent, adjoining nation called the Republic of Cascadia, which ruled itself but remained alongside the United States in views, politics, and trade. The name “Cascasdia” referenced the beautiful, wild mountains and their cascading waterfalls. In fact, one of the driving forces behind the idea was the natural barrier formed by the Rocky Mountains. Mother Nature appeared to have already created a border, and we needed to recognize and respect it. Even though later attempts at complete secession failed, 1940s movements tried to cement some sort of independence from the government. None saw enough success to fulfill Jefferson’s dream.

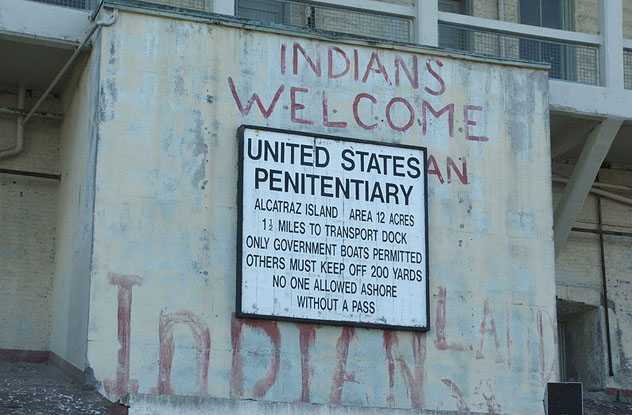

5The Occupation Of Alcatraz

In the 1950s, President Eisenhower signed bills to put Native American reservations back under government control, displacing countless people from land that they’d long called home. In retaliation, several groups tried to occupy the unused island of Alcatraz. The first occupation, in 1964, lasted only four hours but set the tone and the list of demands. Occupiers wanted Alcatraz returned to the Sioux, under the rules of an 1868 treaty that said unused federal land defaults back to Indian control. The second occupation didn’t last much longer before the Coast Guard broke it up, but the third lasted from November 20, 1969 until federal marshals ended it on June 10, 1971. The movement began as a symbolic claim made by a few people; it was extremely well organized, and they were prepared for a long occupation. A functioning community formed on the island while the occupiers demanded that the island be converted into a university and museum dedicated to Sioux heritage. The federal government ordered the occupation to end but then agreed to negotiate. Real negotiations never happened, though; negotiators simply rejected every demand. The government then stopped trying to shut down the occupation and just barricaded the island so the colony would self-destruct. The meltdown started largely due to the hippie drug culture of nearby San Francisco leaking in, turning the occupation from a cause to a free-for-all. Eventually, federal marshals did storm the island, forcefully removing the handful of protesters that remained. Though the occupation raised some awareness, it failed to accomplish anything else.

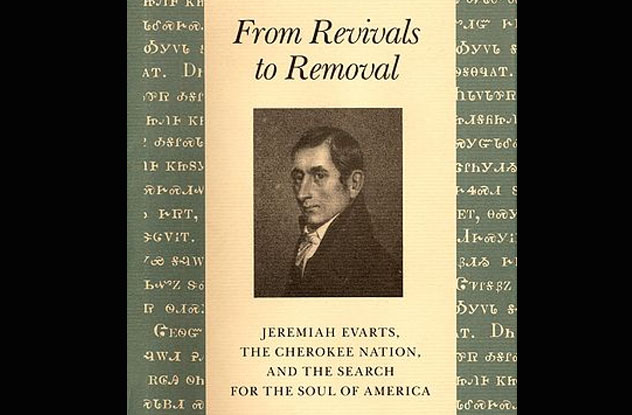

4Jeremiah Evarts Versus The Indian Removal Act

Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830 (even though he perhaps had Cherokee allies during his military career to thank for saving his life). One of the most outspoken critics of the plan was missionary Jeremiah Evarts, head of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Most of Evarts’s work with the board involved traveling through Indian land, and his conclusions about their worth as citizens were at odds with the ideas of the government at the time. Evarts wrote on the tribes’ ability to conform to a European standard of life when afforded access to schools, farmland, and tools. He also cited a moral responsibility that the country had to all its people, whether native or European. He stated that those who had been on the land before European settlers should be able to stay there. Regardless of how civilized or uncivilized they were perceived to be, they should have the same rights that other people enjoyed. The government based many of its actions around the notion that they were creating treaties with the different groups, but Evarts pointed out that the Constitution only gave them the right to form treaties with other nations, so their actions were absolutely unconstitutional.

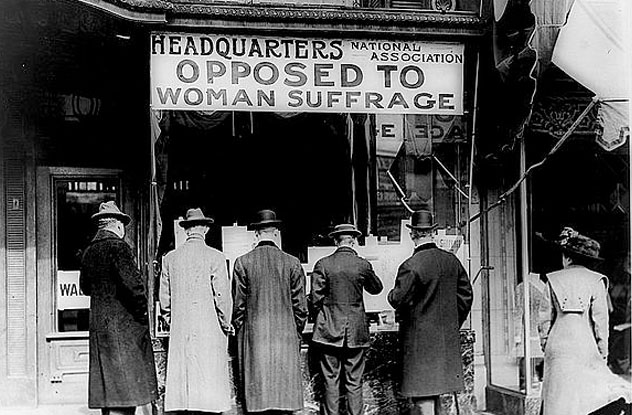

3The Women Of The Anti-Suffragette Movement

After World War I, women in America started demanding the right to vote, and it was far from a cut-and-dried debate. We’ve all heard stories of the women who championed the right to vote, but less known is the perspective of the losing side. Those opposed to giving women the right to vote were anti-suffragettes, and the majority of them were women. By 1911, the scattered anti-suffragette movements that had been popping up across the country combined to form the National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS), all under the leadership of a woman named Josephine Dodge. As a member of one of New York City’s trendsetting families, Dodge was first known for establishing day cares responsible for looking after the children of immigrants. As early as 20 years before the establishment of the NAOWS, Dodge had already presented her views on women’s suffrage in virtually every outlet she could find. She stated that women being allowed to vote was simply unnecessary; more than that, it would hurt the social work in which women were instrumental. She also stated that causes important to women, like child labor laws and women’s wages, had already been fairly established without help from women themselves. According to the NAOWS and the state-based organizations that it spawned, voting would severely and negatively affect the true submissive and domestic state of the feminine. These organizations were championed by women who thought themselves the prime examples of true womanhood—quiet, dignified, and regal. They looked with disdain at the outward protests of suffragettes. But in the end, quiet and dignified didn’t help their cause.

2Prescott Bush’s Nazi Involvement

Prescott Bush was the patriarch of one of America’s political powerhouse families. After serving in World War I, he used his family finance connections to get in on the ground floor with a company called Union Banking Corporation. A director by the time World War II came around, Bush led a company that would eventually lose their assets to the Trading with the Enemy Act. Recently declassified documents reveal that Bush provided a safe place for Nazi interests in America, along with a front for moving Nazi money worldwide. Bush’s company was the American haven for funds funneled into the states by one of Hitler’s major financiers, industrialist Fritz Thyssen. Newspaper reports at the time speculated that that Bush kept a Nazi nest egg safe from prying hands should anything go south. Go south it did, but Thyssen’s money was seized by the US government in 1942 before it could be rerouted back into Nazi Germany. The up-and-coming Bush family was still pretty powerful, and there was no fallout for the discovery of Prescott Bush’s Nazi shell company. It’s not clear if the banking scandal was just business or if it was partly because Bush supported Nazi ideals in any way. But in 1944, FDR issued an executive order stating that the government needed to act to save European Jews. The order fell through, and two Holocaust survivors in a lawsuit blamed this on pushback from the Bush family. Prescott Bush was once considered a viable presidential candidate, and his election may have greatly changed the landscape of American politics.

1The Alien And Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were signed into law by President John Adams, and had they lasted much beyond his term, they would have had some pretty powerful consequences for America. The Alien Act stated that if the United States were at war, the government could apprehend, jail, or deport any non-citizen and seize all their property. It kept immigrants from becoming citizens—instead of spending five years in the country before applying, they suddenly needed 14 years. The law aimed to keep out not just America’s newest enemy—the French—but any other groups such as the Irish coming to the country to cause trouble. According to the Sedition Act, anyone caught organizing a movement against the government, conspiring against the government, or even voicing displeasure with the government could be fined and arrested. Those who dared to write or speak any falsehoods—or simply anything malicious—about the government could also be fined and jailed for up to two years. Newspaper editors were jailed when stories that ran in their papers criticized the actions of the government; in an unsurprising twist, these actions did little to gain political support for those who had written the laws. Fortunately, the laws weren’t popular ones. James Madison called the laws a disgrace, and when Thomas Jefferson followed Adams as president, he allowed the acts to expire. Read More: Twitter