Despite numerous attempts between the 1520s and the 1600s to establish permanent, successful colonies in the modern US and Canada, nearly all of them failed—Santa Fe and St. Augustine being the famous exceptions. Colonial life was hard, and the early Europeans lacked the supplies, tools, and geographic knowledge they needed to thrive in the New World. In this list, we’re exploring ten of the most notable failed attempts to settle North America.

10 San Miguel De Gualdape

1526

In 1521, a Spanish expedition set out to explore South Carolina. They returned to Cuba with 60 captives and a glowing report of a land that would make a great colony, populated by friendly natives who wouldn’t need to be conquered. A wealthy local official, Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon, was impressed by their report and soon got permission from the Spanish crown to found a new settlement in the land. Ayllon indebted himself funding the expedition of six ships and 600 colonists. Laden with supplies, they departed in July 1526 to found the first European colony in North America since the Vikings over five centuries before.[1] They soon ran into trouble. After they landed in Winyah Bay in August, their native pathfinders abandoned them, and their flagship sank, taking many of their supplies with it. Finding the land unsuitable for building a settlement, Ayllon organized a wide-ranging scouting mission. Based on the scouts’ reports, they headed toward another site over 320 kilometers (200 mi) away, which they finally reached in late September. They christened the new town San Miguel de Gualdape after the feast day of Saint Michael. It was too late in the year to plant any crops, and the natives were unwilling to trade. The weather was much colder than they had expected, and disease, especially dysentery, killed many and made more unable to work. In early October, Ayllon himself died, and the colonists split into two groups, one wanting to stay and wait for resupply and the other wanting to abandon the colony. The dispute broke out into a full-blown mutiny in which the leading rebels were captured, and their homes were burned down by slaves. By November, the survivors had decided to abandon the settlement, but only after three quarters of the colonists had died.

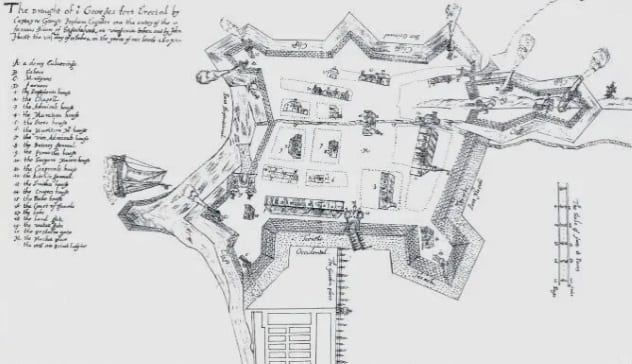

9 Charlesbourg-Royal

1541

The next settlement to be built in North America was founded by Jacques Cartier, who had spent many years surveying the coast of Canada with the original aim of finding a safe sea route to China. Though he was unsuccessful, he did note several spots that he thought would be good places to settle, and with the king’s permission, he established a colony of roughly 400 people in modern-day Cap Rouge sometime between June and September 1541.[2] He named this settlement Charlesbourg-Royal after Charles II, duke of Orleans. At first, the colony was successful, surviving its first winter despite the harsh Canadian weather and being on neutral, if not friendly, terms with the native Iroquoians. They built a fort in two sections, one by the base of the river to protect the ships and houses and another at the top of a nearby hill for defense. The colonists went hunting for precious metals and found piles of diamonds and gold. It seems, however, that Cartier struggled to discipline his men, and unruly engagements with the Iroqouians turned them hostile. While they were supposed to wait for the arrival of de Roberval, the official leader of the expedition, Cartier and his men believed the colony would fail and departed for France in June 1542, slipping past de Roberval’s vessel under the cover of night. When he arrived in France, however, Cartier learned that the diamonds and gold they’d thought they’d found were actually worthless (but very similar-looking) minerals. De Roberval took over control of the settlement, but the situation only worsened, and they abandoned it in 1543 after disease, bad weather, and clashes with the natives made the fort uninhabitable.

8 Fort Caroline

1564

St. Augustine is famous today for being the oldest continually inhabited European settlement in North America. The story could have been much different, though. In June 1564, a year before St. Augustine was founded, 200 French colonists built Fort Caroline on the Northeastern Florida coast.[3] The fort’s garrison struggled to contain bouts of mutiny while they wrestled with attacks by the natives, hunger, and disease. The fort persisted, though the morale of its inhabitants was very low by the time the Spanish learned of its existence in early 1565. The fort was reinforced by Jean Ribault and hundreds more colonists and soldiers in August, but by that time, the Spanish government had already organized an expedition to conquer it. The Spanish expedition, led by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, sailed up the northern coast but ran into Ribault’s fleet, who drove them off. The Spanish soldiers made landfall further south and built a fort. This fort would come to be known as St. Augustine. Ribault gathered an army of 600 and sailed south to destroy the new fort, but his fleet was hampered by a sudden storm. Menendez took advantage of the weather and marched overland to Fort Caroline, launching a surprise attack in September and seizing it, killing all inside except 50 women and children. The Spanish burned the fort down, but Fort Caroline continued as a rebuilt Spanish outpost until 1568, when a French adventurer, de Gourgues, burned it down in revenge.

7 Santa Elena

1566

Two years before Ribault built Fort Caroline, he and his followers had founded Charlesfort further up the coast, in modern-day South Carolina. The settlement failed within a few months, and they ultimately moved to Fort Caroline. However, Menendez (pictured above), whether to add insult to injury to Ribault or because he liked the site, decided to resettle Charlesfort as the Spanish colony of Santa Elena. It was intended to be the capital of Spanish Florida, and the government was moved there from St. Augustine in 1566.[4] Santa Elena quickly became the center of military and religious missions going north, particularly for Juan Pardo’s expedition, which established a string of short-lived forts up the Appalachian mountain range, the furthest European colonists would venture inland for another century. Santa Elena itself was, alongside St. Augustine, the first successful long-term European colony in North America, thriving until it was attacked and burned by natives in 1576. The Spanish returned next year, and in 1580, they successfully pushed back an attack by 2,000 natives. Despite Santa Elena’s size and heavy fortification, however, the Spanish ultimately lost interest in the Carolinas and abandoned the settlement in 1587, choosing to focus their efforts on Central America instead.

6 Fort San Juan

1567

Following the colonization of Santa Elena, the Spanish crown planned to extend its influence inland through what they called La Florida—modern-day North and South Carolina. The goal was to find an overland route to Mexico which the Spanish could use to transport silver to St. Augustine and ship to Europe without having to contest the dangerous Caribbean waters. This expedition was led by Juan Pardo, who took a force of 125 men with him. They soon came across the native town of Joara. Renaming it Cuenca and claiming it for Spain, the Spanish built a fort to control the town, Fort San Juan, and left a garrison of 30 to protect it before moving on.[5] They built five more forts across the Carolinas, but none were as big as San Juan. Pardo never made it to Mexico: Hearing of a French raid on Santa Elena, he turned back and headed straight for the Floridian capital. He never returned to the Carolinas. Soon after the main body of troops had returned to Florida, the natives turned on the Spanish and burned down all six forts, killing all but one of the Spanish soldiers, who only escaped by hiding in the woods. The Spanish never returned to the North American interior, considering the venture a huge failure.

5 Ajacan Mission

1570

In 1561, a Spanish expedition to Virginia captured a Native American boy. He was taken to Mexico, raised as a Catholic, and christened as Don Luis. He was taken to Madrid and even met the Spanish king before he became part of another Spanish expedition back to Virginia in 1570.[6] Father de Segura, an influential Jesuit in Cuba, planned to establish an unarmed religious mission in Virginia. While it was considered highly unusual at the time to send a mission without soldiers, he was granted permission. He and seven other Jesuits, a Spanish boy, and Don Luis, their interpreter and guide, set off for Virginia in August 1570. They arrived in September and built a small wooden mission before establishing contact with the nearby native tribes. Don Luis told them he wanted to find his home village, which he hadn’t seen in roughly a decade. The Jesuits let him go. As time went on, the Jesuits became increasingly concerned that Don Luis had abandoned them. They tried to find him, since they couldn’t communicate with the natives without his help. In February 1571, three of the Jesuits found Don Luis’s village. Don Luis and the natives killed them, and then he led the native warriors to the mission, where the rest of the Jesuits were executed. Only the Spanish boy was spared. He was taken back to the village. In 1572, a Spanish expedition returned and recovered the boy, killing 20 natives in retaliation. The mission was abandoned, however, and the Spanish never returned to Virginia.

4 Roanoke

1585

In 1584, Queen Elizabeth granted Walter Raleigh a charter giving him the right to establish a colony in North America. His goal was to establish a base from which to harass the Spanish treasure fleet, which was the main artery of Spain’s economy at the time, and also for future exploration of the continent. While Raleigh never visited North America himself, he financed and organized an expedition in 1584 which scouted out the area of modern-day North Carolina, mapping the region and bringing back two natives with knowledge of the tribal relationships in the area. Based on this, Raleigh organized a second expedition in 1585. They landed in Roanoke in August and established a small colony of around 100 people.[7] The fleet then returned to England to bring more supplies. In June 1586, the settlement was attacked by natives. Sir Francis Drake stopped at the colony shortly after and picked up the colonists, taking them back to England. The original fleet returned with supplies from England after that and, finding the colony abandoned, left a small contingent of 15 men behind to hold the island in Raleigh’s name before returning to England. In 1587, Raleigh dispatched another 115 colonists to collect the contingent and take them to the Chesapeake Bay, where a new colony would be built. When they arrived in Roanoke, however, all they found of the 15 men was a single skeleton. The new colonists remained in Roanoke instead, and the fleet returned to England to find help and support. Unfortunately, the outbreak of war with Spain made the long sea voyage almost impossible, and it was late 1590 when the fleet was once again able to make it to Roanoke. They returned to find the settlement abandoned. There was no sign of a struggle, and the buildings had been dismantled in an orderly way, suggesting there was no rush to leave. All they found was the word “CROATOAN” carved into a fence post, and the letters “CRO” on a nearby tree. Since the colonists had agreed to carve a Maltese cross if they’d had any difficulty, it was assumed that the colonists had moved to the nearby Croatoan Island. Bad weather prevented the English from checking, however, and they returned home. The English didn’t return until the colonization of Jamestown 17 years later, and they never found any definite trace of the Roanoke colonists.

3 Saint Croix Island

1604

Today, Saint Croix Island is an uninhabited island off the coast of Maine, with no public access. In the early 1600s, though, it was the site of an early French colony that was supposed to be the first permanently occupied (instead of seasonal) settlement in the region the French called Acadia, or l’Acardie. Since the failure of Charlesbourg-Royal some 60 years before, the French crown had shown little interest in modern-day Canada. But after the attempts to colonize Sable Island in 1598 and Tadoussac in 1600, French interest in Canada was growing again. Saint Croix was chosen after considerable surveying of the region had identified the best possible locations for settlements.[8] The island seemed ideal: Well-defended from both the natives and the English, it could only be attacked from one direction by boat, which made it very defensible. The soil was good, and there were plenty of trees. In the early days of the colony, morale was high, and the settlement was established very quickly. Natives even visited to study the colony and asked the French to mediate their disputes. However, it began to snow on October 6. The winter had come earlier than expected and lingered a long time, sealing the settlers on the island as the river froze over. Many succumbed to a strange “land disease” which made their teeth fall out and sapped their energy. Later analysis of their bones revealed that they were plagued by scurvy. When the original leader of their expedition, Francois Dupont, returned in June the next year with boatloads of supplies, they made the decision to move to a different site. The buildings were dismantled and shipped across the bay to the new site of Port-Royal.

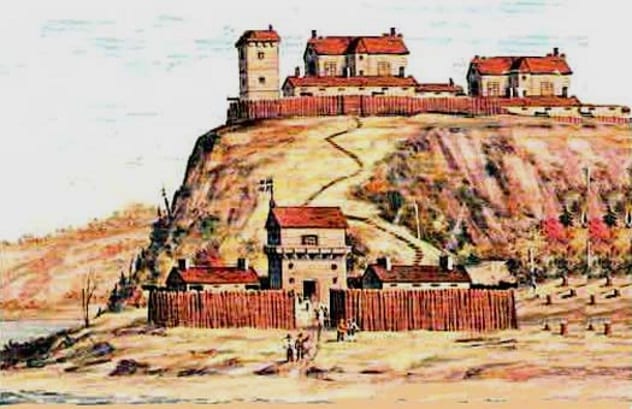

2 Port-Royal

1605

Port-Royal (replica pictured above) was a much better-suited location for a thriving settlement.[9] Located on the shore of a huge bay, the French envisioned it as potentially mooring hundreds of ships one day, so they gave it the name Port-Royal, or Royal Port. They built their first settlement against the northern mountains by felling trees and putting up a simple wooden palisade around the buildings for protection. Supported by the fertile soil and temperate climate, and assisted by the nearby Mikmaq people, they prospered. Concerned about the low morale at Saint Croix, they even established a social club which hosted frequent feasts and art shows, including theater productions. However, the colony had to be abandoned in 1607 after its founder, Pierre Dugua de Mons, had his fur-trading license revoked, removing the colony’s main source of income. The colony was left in the hands of the Mikmaq and recolonized by a small French expedition in 1610. The colony never grew to any considerable size, however, and conflicts over the involvement of the Jesuits in the colony led to divisions. It was burned to the ground while the colonists were out by the English adventurer Samuel Argall. The colony was abandoned once again, and the settlers went to live among the Mikmaq.

1 Popham Colony

1607

Encouraged by growing English interest in North America, King James invested two companies with the rights to settle New England: the London Company and the Plymouth Company, both of which were parts of the Virginia Company.[10] To foster competition, the king specified that the company whose colony was most successful would win the rights to own the land that lay between them. After a flurry of excitement and investment, the London Company established their colony of Jamestown in Virginia, and the Plymouth company settled theirs at Popham in Maine. Unlike the Jamestown colony, which lost over half of its people to disease, the Popham colony was largely successful to begin with. Things took a turn, however, when they were unable to trade with the natives as much as they’d expected, and their leader, George Popham, died in 1608. They continued their efforts to expand the colony despite this, even building the first-ever English seafaring ship in North America, the Virginia. The winter was bitterly cold. The colonists complained about the unceasing snow. A fire burned down the storehouse, destroying most of their supplies. Following food shortages, over half the colonists chose to return to England on the next supply ship. The remaining colonists were determined to continue on, however, and the summer was better. The settlement was ultimately brought down by a crisis not in America but in England. A supply ship arrived carrying news that the colony’s new governor, Raleigh Gilbert, had inherited his family’s lands in England following his brother’s death. Raleigh decided to return to England. Unwilling to face the prospect of another harsh winter—this time without a leader—the rest of the colonists glumly agreed to return to England with him.