Maybe the word “mummy” makes us think of the human remains resting in the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily. They are fascinating and creepy at the same time. Mummies pop up all over the globe and through all time periods. But no matter how diverse they are, they have one thing in common: The process of mummification always occurs after death. Or does it? There’s at least one weird exception to the rule. A certain sect of Buddhist monks in Japan decided to turn their bodies into mummies while they were still alive. These monks practiced self-mummification to become sokushinbutsu (“Buddhas in the flesh”).

10 Why Would Anyone Do This?

Self-mummification sounds like a bad idea. Who would want to do such a thing? The first person who aspired to become a living mummy was a man named Kukai, later known as Kobo Daishi. Kukai was a Buddhist priest who lived more than 1,000 years ago in Japan. During his lifetime, he founded the Shingon (“True Words”), a new sect of Buddhism. Kukai and his followers were convinced that spiritual power and enlightenment could be achieved through self-denial and an ascetic lifestyle. A Shingon monk could easily be found sitting for hours under an ice-cold waterfall, ignoring his body’s needs while meditating. Inspired by Tantric practices from China, Kukai decided to take his ascetic lifestyle to the extreme. His aim was to leave behind the restrictions of the physical world and become a sokushinbutsu. To achieve this, Kukai took certain measures that turned his body into a mummy while he was still alive.

9 The First 1,000 Days Are Hard

The actual process of turning oneself into a mummy is long and grueling. There are three stages, each lasting 1,000 days, that ultimately lead to a mummified body. During those roughly nine years, the monk is alive for most of the time. After the monk decides to attempt self-mummification, he enters the first stage. The monk completely changes his diet, eating nothing but nuts, seeds, fruits, and berries. This restricted diet is combined with a rigorous schedule of physical activity. During these first 1,000 days, the monk rapidly loses body fat. Mummification needs dry conditions to take place—the drier, the better. But body fat has high water content that causes quicker decomposition after death. Corpses with a lot of body fat also retain heat for a much longer time. Heat leads to better reproduction of the bacteria that promote decomposition. The monk’s loss of body fat is the first step in his fight against the body’s decomposition after death.

8 The Next 1,000 Days Are Even Harder

The next stage is marked by an even more restricted diet. For the next 1,000 days, the monk only eats bark and roots in gradually diminishing amounts. Physical activity is replaced by long hours of meditation. As a result, the monk loses even more body fat and muscle. These efforts to become emaciated ultimately combat the body’s decomposition after death. Bacteria and insects are the two main factors involved in the decomposition of a body. After death, bacteria within the body start to break down cells and organs. Although these bacteria cause the body to disintegrate from inside, the soft and fatty tissues of the dead body are also an invitation for flies to lay their eggs. Maggots soon hatch and feast on a diet of rotting flesh mixed with fat. At the end of the process, all soft tissue has completely vanished, leaving only the bones and teeth of the dead body. The monk’s extreme diet literally takes away the critters’ food.

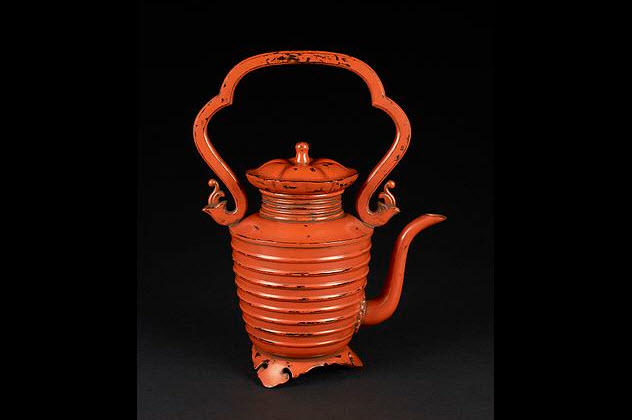

7 You’re Going To Vomit Your Guts Out

The second 1,000 days of asceticism leave the monk’s body emaciated. As body fat drops to a minimum, constant meditation and almost no physical activity leads to the loss of muscular tissue. But the monk still isn’t satisfied and takes his ruthless diet even further. During his final steps to becoming a sokushinbutsu, the monk drinks tea made from the sap of the urushi tree. Usually, this sap is used as a varnish for bowls or furniture. It is highly toxic. Drinking the urushi tea quickly leads to heavy vomiting, sweating, and urination. This dehydrates the monk’s body and creates ideal conditions for mummification. In addition, the poison from the urushi tree builds up in the monk’s body, killing maggots and insects that may try to infest the body after death.

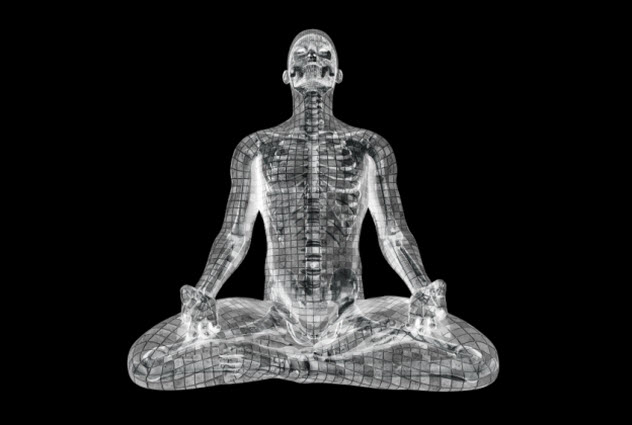

6 You’re Going To Get Buried Alive

After 2,000 days of torturous fasting, meditation, and the consumption of actual poison, the monk is ready to leave this plane of existence. The second stage of sokushinbutsu ends with the monk climbing into a stone tomb. The tomb is small, barely allowing him to sit. The walls and ceiling are so narrow that the monk is unable to stand or even turn around. After the monk assumes the lotus position, his assistants close the tomb, literally burying him alive. Only a small bamboo tube connects the tomb with the outside world to grant the monk some air. He sits in his dark, narrow hole with only a small bell as a companion. Each day, the monk rings the bell to let his assistants know that he’s still alive. When the assistants no longer hear the bell, they pull the bamboo tube from the tomb and completely seal it up, leaving the monk in what has now become his grave.

5 The Last 1,000 Days

In the final 1,000 days, the sealed tomb is left alone while the body inside turns into a mummy. The low body fat and muscle tissue prevent the normal putrefaction of the body. This is supported by the dehydration of the body and the accumulation of urushi. The monk’s body dries up and slowly mummifies. After 1,000 days, the tomb is opened and the mummified monk is removed from his dying place. His mortal remains are returned to the temple and worshiped as a sokushinbutsu, a living Buddha. The monk will be admired and cared for. The priests even go so far as to change his clothes every few years so that the new Buddha will look his best. The monk—whether he has ascended to a higher plane of meditation or is really just dead—will never recognize his own success.

4 There’s A High Chance That You’re Going To Fail

In the 1,000 years since Kukai pioneered the process of self-mummification, it’s believed that hundreds of monks have tried to become living mummies. We only know of about two dozen monks who were successful. Obviously, there’s a high failure rate. The road to becoming a Buddha in the flesh is a bumpy one. For over five years, the aspiring sokushinbutsu eats almost nothing, engages in almost no physical activity, and endures long hours of meditation. It’s probably safe to assume that few people have the self-control and willpower to suffer this way for up to 2,000 days. Many monks may have simply given up. Even if they did continue with this ascetic lifestyle until the end, there is still a high probability that their bodies didn’t turn into mummies after death. The humid climate and acrid soil in Japan are bad conditions for mummification. Despite all his efforts, the monk’s body might decompose inside its tomb. In these cases, the monk would not be revered as a living Buddha. His remains would simply be reburied. However, he’d be highly respected for his endurance.

3 You’re Going To Break Some Laws

Self-mummification was practiced in Japan from the 11th century until the 19th century. In 1877, Emperor Meiji decided to put a stop to this form of suicide. A new law was issued that forbade the opening of the grave of someone who had attempted sokushinbutsu. As far as we know, the last sokushinbutsu is the mummy of Tetsuryukai. For years, Tetsuryukai had practiced the ascetic lifestyle to become a living mummy. When the law was enacted, his endeavor suddenly became illegal. He proceeded with his rites anyway and was sealed in his tomb in 1878. After the final 1,000 days were up, his followers had a problem. They wanted to open the grave to see if Tetsuryukai had become a sokushinbutsu, but they didn’t want to go to prison. So they sneaked to the grave one night, dug up Tetsuryukai, and found that he had turned into a mummy. They wanted to display the body of their new Buddha in the temple. To avoid prosecution, Tetsuryukai’s followers changed his date of death to 1862, which was prior to the new law. Tetsuryukai is still enshrined at Nangaku Temple.

2 The Who’s Who Of Self-Mummification

Although many monks tried to become sokushinbutsu after Kukai, only around two dozen are known to have been successful. Some of these mummified monks can be visited in Buddhist temples in Japan and are deeply revered by Buddhists to this day. The most famous sokushinbutsu is probably the monk Shinnyokai-Shonin, whose remains can be found in the Dainichi-Boo Temple on Mount Yudono. Shinnyokai began dreaming of becoming a sokushinbutsu in his twenties and had already restricted his diet by that time. But he didn’t fulfill his dream until 1784 when he was 96 years old. At the time, the famine of Tenmei raged on Honshu, the central Japanese island. Hundreds of thousands of people died from starvation or disease. Shinnyokai was convinced that Buddha needed a sign of compassion to finally end the famine. So he dug a grave on a hill near the temple and sealed himself inside. While Shinnyokai sat in his grave and waited for death, only a thin bamboo tube allowed him to breathe. Three years later, the grave was reopened and revealed the completely mummified remains of the monk. Whether or not it was related to Shinnyokai, the famine finally ended in 1787.

1 The Newest Buddhist Mummy

In January 2015, the old sokushinbutsu were joined by a new Buddhist mummy. This time, the mummified monk was from Mongolia. The monk was discovered by police as he was transported to the black market for sale. His remains were recovered and brought to the National Center of Forensic Expertise in Ulaanbaatar. Like his Japanese counterparts, the Mongolian monk is sitting in the lotus position. He still looks like he’s in deep meditation and didn’t notice when he died. In fact, some senior Buddhists believe that the monk isn’t dead at all. They think that he’s simply in a meditative state on his way to becoming a Buddha. However, scientists are convinced that the monk has been dead for 200 years. Either way, this Mongolian monk had an advantage over the Japanese monks who turned themselves into mummies. Unlike Japan’s humid climate, the dry, cold weather of Mongolia supports a natural process of mummification.