Because it isn’t exactly a dramatic revelation, human error makes only 10th place (they get more interesting). In terms of probability, those who have no interest in the supernatural — or as yet misunderstood science — will usually stop with all the ships and planes wrecking in the Triangle as a result solely of human error. Humans make a lot of them. Even the most well trained, seasoned pilot’s concentration can momentarily lapse, and that is sometimes all it takes for disaster. The most famous plane wreck of the Triangle’s storied history is that of Flight 19, on 5 December 1945. The flight leader was Lieutenant Charles Taylor, a Naval Air Corps flight instructor. This story in particular will never let the Triangle’s mystique die, because Taylor was no rookie at the controls. They were supposed to practice dry bombing runs over the Florida keys, south of Florida, but somehow became so disoriented on the way home that they flew out over the Bahamas. Then all 14 airmen crashed into the open sea well northeast of Florida and were never heard from again. A rescue party of 13 in a PBM Mariner was dispatched to search, but this plane is thought to have blown up in mid-air from an unknown cause. Extremely strange occurrences for professional military airmen, but it can always happen. Taylor’s radio transmissions have been preserved and indicate that his compass malfunctioned (see #5). Because he could no longer find magnetic North, he and his crew attempted to return West to the Florida coast by keeping the afternoon sun in front of them. This still did not succeed and the military’s explanation for the flight bewilderment is that Taylor mistook outline of the Bahama islands for the coastline of Florida.

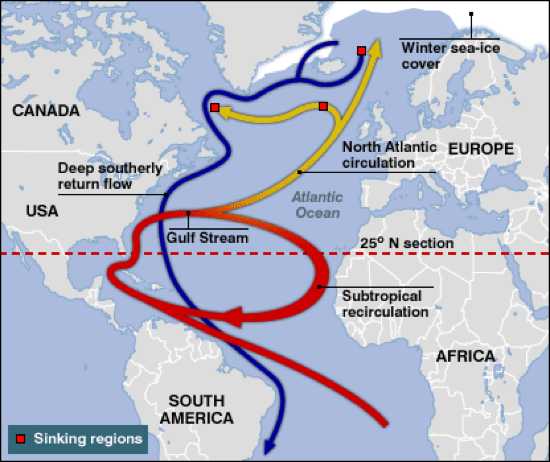

In explaining why no wreckage of various ships and downed planes has ever been found in the fairly shallow waters, the Gulf Stream is typically blamed. It is, in effect, a saltwater river on the surface of the ocean, with a warmer temperature than the surrounding seawater, causing it to flow northward along the east coast of the U. S. The current itself is in most place along the coast about 60 miles wide, and 2500 to 4000 feet deep, flowing on the surface at about 8 feet per second, with more than sufficient strength to drive enough hydroelectric plants to power all of North America. The Stream is nowhere stronger or faster on the surface than in the Triangle. When ships sink or planes impact the water, they float momentarily, up to several hours depending on the severity of the vessel’s damage. During that time, the wreckage is carried northward by the Stream until sinks below the Stream, and finally to the bottom of the sea. Thus, a vessel could encounter disaster at one location and reach its final resting place in another. When rescuers reach the scene of last communication, they may find only the ocean, and may search a radius of several hundred square miles without finding a shred of anything. This doesn’t explain why so many ships and planes go down in the Triangle, but it can explain why almost immediate rescue efforts and subsequent deep-sea salvage operations turn up nothing at all.

Rogue waves were only theorised by science for centuries, until proof was established on 1 January 1995, at the Draupner oil rig off Norway. In rough seas with average waves of 39 feet, the oil rig was too high to be touched, until a single wave of at least 85 feet slammed across the underside, causing minor damage. It was recorded on sensors and proved what superstitious sailors had been swearing to in the same drunken tales of sea monsters. The waves are possibly the most terrifying occurrences on the ocean. There can be no prior warning of them, no mathematical computation involving where and when they might occur. They are simply several dozen waves of average height for the conditions that suddenly merge into one and climb and climb. Their maximum limits are not known. An 85 footer is quite small. A 157 footer struck Fastnet Lighthouse, Ireland, in 1985. Such gigantic, nearly vertical walls of water are easily capable of flipping super tankers and sinking them in seconds. The largest ever ship was the Knock Nevis or Seawise Giant, at 1503 feet long. Titanic was only 882.5 feet. The Knock Nevis would have had to turn straight into a rogue wave and surf it in order not to turn over and founder, and even then, a 157 footer might still sink it. Rogue waves are not caused by any one factor, but high winds and strong currents routinely cause waves to merge. They are still rare, occurring only about once every 200,000 waves. They are somewhat more prevalent in the Triangle than in calm areas of the world’s oceans, because of hurricanes and the Gulf Stream itself. A 157 foot high wave can utterly immerse and knock down any low-flying airplane or helicopter, especially those of the Coast Guard rescue, which fly low to search for shipwrecks and their survivors.

These are more properly called “methane clathrates,” which in water environments are hydrates. How many are present around the world, and how large they are is unknown. A methane hydrate deposit is methane gas trapped in a natural lattice structure of crystallised water, similar to ice. Such deposits lie under the seafloor at almost any depth, some only inches beneath the water. Depending on their size, they can possess colossal potential energy, and when released all at once, the eruption can be sufficient to cause oil well blowouts. It was a methane hydrate that caused the Deepwater Horizon Disaster in 2010. The oil drill finally struck the hydrate deposit submerged in the ocean of oil beneath the seabed, and the methane destroyed the entire rig, sinking it a mile to the bottom. It is quite plausible that a methane hydrate could erupt from under the seabed, expelling methane gas hundreds of feet to several miles all the way to the surface, and at the surface, a passing ship of any size could find itself centered over the escaping gas. If this occurs, the methane gas would turn the area around the ship to froth, severely decreasing the water’s buoyancy, and cause any ship, from a wood rowboat to a super tanker to sink in less than 10 seconds. No one on board would be able to abandon ship fast enough. The ocean itself would, in effect, swallow the vessel whole.

The Bermuda Triangle stares down both barrels of Hurricane Alley each year. It’s rather easy to avoid one at sea, since any able seafarer will pay close attention to weather reports of it and have a week or more of prior warning to get out of the area. But that’s the case with modern technology. The Triangle’s mysterious disappearances date back to the Spanish and Portuguese conquistador era. The most unpredictable, and thus most dangerous, by-product of a hurricane is a microburst, a sudden downdraft caused by the storm’s rotation sucking air down from high altitude. When this air reaches the surface of the ground or water, it spreads outward at speeds over 170 mph, regardless of the Hurricane’s category strength, more than sufficient to snap full-grown oak trees, or flip over any ship in the world. Airplanes are at risk of being forced into a stall and nosedive. Well trained pilots and helmsmen routinely fall prey to microbursts, and once they sink, the phrase “without a trace” is redundant given the Gulf Stream and the size of the ocean.

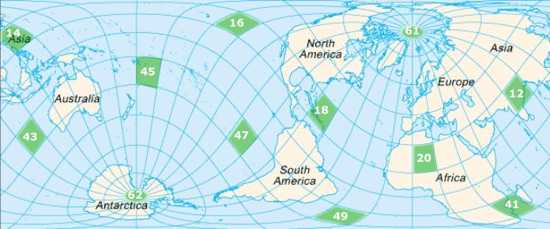

Popularly thought of as a hole in Earth’s electromagnetic field. There are multiple places on Earth where a compass will not point North. Of course, compasses point to magnetic north, and as a compass travels across Earth’s surface, the needle will be seen to move in relation to the magnetic pole, and is quite incorrect in pointing to true North. Nevertheless, compasses behave very strangely in some places around the world. At either magnetic pole, the needle will spin. At the actual North or South Pole, the needle will point to magnetic North, and thus be incorrect. In the Gobi Desert, some of the Altai Mountains are made of naturally magnetic stone, and within 100 miles of them, compasses will spin if surrounded, or simply follow the mountains as they pass by. Compasses also behave erratically in the Bermuda Triangle. If you pass through any of its three borders, the aberrations will not cease instantaneously, but these reported electromagnetic aberrations can be plotted on a map with a center squarely in the Triangle. One or two mariners over the centuries could be referred to entry #10, but several thousand maritime travellers, in vehicles from small boats to large ships and airplanes, have complained of being unable to rely on their compasses during sections of their journeys through the Triangle. It is open ocean, and no submerged anomalies have ever been reported. The sea floor has been completely mapped with sonar. Shipwrecks and plane wrecks are not magnetic, and have no bearing on compasses. Whatever causes the electromagnetic disturbances affects compasses very rarely, but there are many reports of needles intermittently spinning or spiking. It’s easy enough to navigate via the sun or stars, provided they’re visible, but the aberrant behaviour of compasses remains a mystery, and a likely cause of at least some of the disasters.

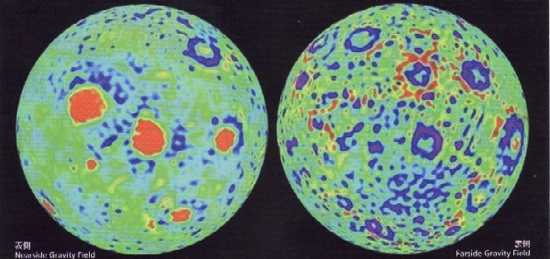

“Mascon” is short for “mass concentration,” in this case of gravity. Gravitational mascons were theorised once the space age reached full gear, but they were, until the 1970s, only thought to exist in extremely massive celestial bodies, such as the Sun. Today, we know better. There are positive and negative mascons under every single square inch of every celestial body in the Universe. No one knows exactly what causes them, but nowhere in the known Universe are they more pronounced than on the Moon. Astronauts from the 1960s on recorded noticeable dips in the orbits of satellites around the Moon, both manned and unmanned. These dips usually coincided with the Moon’s “seas,” such as the Sea of Tranquility, as well as the largest impact craters. It was found that the soil of the seas is made of basalt, which is why they are dark-colorer, and basalt is extremely dense compared to the lighter-colorer soil and rock around it. When an orbiting object passes over one of these seas, the denser material yanks on it with much more gravity than the Moon’s average pull. If Earth is said to have a gravitational pull of 1, the Moon is about 1/6th. Jupiter is 2.53, and a neutron star is 10 to the 11th power, or about enough gravitational pull to overpower 33% of the speed of light. The basalt of the Moon’s seas does not, however, explain the above average gravity centered in its impact craters. The Moon’s mascons are so powerful that no satellite can maintain an orbit for longer than about 4 years without being corrected. Left uncorrected, the satellite passes over multiple mascons until they finally yank it into free fall. You are currently sitting on a mascon, whether negative or positive, but it is so microscopic in size and/or density that you cannot feel it. Nevertheless, gravity pulls slightly less in the Swiss Alps than in Paris, France. Such gravitational discrepancies are present everywhere around us. It is very possible that there are minute, yet unbelievably dense and powerful, positive mascons peppered under the seafloor throughout the Triangle. They may or may not be sufficient to affect seagoing vessels, but combined with a vessel traveling downward in a trough between two waves in rough seas, a mascon may be able to yank a ship underwater in 3 seconds or less, and continue pulling it all the way to the bottom. Since air is a much thinner medium than water, a mascon’s effect is even greater on aircraft, as evident with satellites.

Easy enough to explain, given that they’re still pure science fiction. You could supply your own text to this entry, really. In general, all stories of aliens causing bizarre disappearances in the Triangle center on abductions. Remember, once you say “aliens” anything goes. The aliens are evidently curious about humans and periodically snatch a few from the Triangle for who-knows-what. Spielberg used this theory in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” depicting the airmen of Flight 19 stepping off the mothership at the end. This theory has been put forth to explain the Mary Celeste, though it sailed a few hundred miles north of Bermuda, not through the Triangle. One of the most mysterious ship disappearances is that of the USS Cyclops, an armed Navy bulk cargo ship transporting 11,000 tons of raw manganese for use in munitions. Raw manganese ore is not flammable, so if there was an explosion, the manganese did not cause it. A boiler might have exploded, and that could easily sink even a huge ship, but if so, the wooden parts of the ship scattered across the water would not have sunk, and the Gulf Stream would have carried them northward along the East Coast, likely washing up on Bermuda’s beaches. The Cyclops left Rio de Janeiro on 16 February 1918 for Baltimore, Maryland. It stopped in Bahia, Brazil on schedule on 20 February, then stopped in Barbados for a check to see if it was overloaded. It was deemed secure and seaworthy and departed on 4 March, north through the center of the Triangle, and was never seen again. Stories like this one have given rise to the theory of aliens beaming entire ships and planes into spaceships.

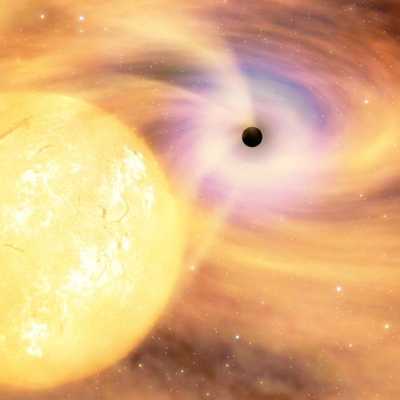

Even less probable than alien adbuctions, but then, how much do we fully understand about Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity? He theorised that space and time combine to form one entity, and that everything in the Universe sits on this space-time, which, in effect, acts and reacts like a fabric suspended at the ends. A very massive object like the Sun rests on and indents this fabric more deeply than a less massive object like Earth. Black holes are just that, holes in the fabric of space-time. What’s on the other side? Today’s mathematics hit a brick wall at that point. No one knows. A rip in the space-time continuum is not necessarily a black hole. Many are called Einstein-Rosen Bridges, or more popularly, wormholes. The shortest distance between two points is, in this case, not a straight line, but zero. The wormhole effectively teleports anything that enters it from Point A to B instantly, regardless of the distance, and Points A and B are not necessarily different physical locations, but could be the same location in different time periods. So you can travel from Earth to some planet in the Upsilon Andromedae star system instantly, rather than spending 44 years traveling at the speed of light. According to General Relativity, superluminal (faster than light) travel is impossible unless the laws of physics are first discarded. It also theorises that the laws of physics cease to exist inside a wormhole. Because a full mathematical description of wormholes has not yet been formulated, it is, at least for now, possible (just not feasible) that a wormhole exists in the Triangle, though not at all times, that this wormhole instantly transports anything entering it to another location in the Universe, or to another time in the same location. Possible credence for this theory centers on Carolyn Cascio, who was mentioned in detail on another list. In brief, she was a veteran pilot who chartered vacations in the Bahamas. On 7 June 1964, she flew from Nassau for Grand Turk Island, the largest of the Turks Islands, and densely populated. It has lots of houses, condos, hotel resorts, an airport, and many other signs that it is inhabited, but when Cascio reached Grand Turk, she radioed ahead that she thought she was lost. She stated that the island was the same shape and size of Grand Turk, but was utterly bereft of any sign of human habitation. It had nothing but woods and beaches on it. Her radio transmissions were received by Grand Turk airport, which radioed back that she was at the right island, and could land anytime, but she didn’t. She radioed that she could not find the airport, even though she was flying directly over it. She circled it over a dozen times, being radioed frantically from the tower, but never responded. Her transmissions indicated that her radio was not receiving, though the airport received hers, and though in full view of it for 30 minutes, she finally flew off back the way she had come, and neither she, nor her passenger, nor her plane was ever seen again. The above story is true. The mathematical theories involved with how wormholes work are not yet fully described, so until the possibility of a wormhole in the Bermuda Triangle is proven or disproven, it must be construed as possible for Cascio to have entered one at Point A sometime during her trip to Grand Turk and exited at the same location in a time, Point B, before humans had inhabited Grand Turk. She was, then, unable to fly back through the same rip in the space-time continuum.

This theory is argued based on the evidence of apparently man-made structures in 15 to 20 feet of water, just off the northwest coast of North Bimini Island, about 50 miles east of Miami, Florida. These structures have come to be called the Bimini Road, and they were only discovered by a scuba diver on 2 September 1968. They are limestone rocks, fairly rectangular for the most part, and all roughly but neatly fitted together as a pavement about half a mile long. There are two other similar structures between this road and the island’s beach, also of limestone blocks. The blocks range in size from 6 feet to 13 feet wide. The other two roads are about 150 feet and 200 feet long, comprised of smaller blocks. The rectangular shape of most of the blocks, as well as their orderly arrangement in straight lines of up to half a mile lead many to surmise that they are man-made, cut from limestone quarries and set up as either a road or wall. The longer road is arranged as if it were a section of wall surrounding North Bimini Island. It may be possible that the Bimini Road is the only remnant of the sunken Island of Atlantis shallow enough to have been discovered. Plato theorised that Atlantis flourished about 9,600 BC, and had been far advanced technologically, artistically, and politically beyond his Ancient Greece, the most advanced society in the world at the time. He described it as having lain “in front of the Pillars of Heracles,” which are the Strait of Gibraltar, and that because of a horrible cataclysm, perhaps a volcanic eruption, “in one single day and night of misfortune, the Island of Atlas vanished from the face of the earth.” It is no secret that there may have been such an island; the Atlantic Ocean is named after the same root, Atlas. If Atlantis is there at the bottom of the ocean, perhaps its civilisation was so technologically advanced as to survive submerging to an average Bermuda Triangle depth of about 3.8 miles. Sonar bathymetry maps do not show any anomalous underwater features in the Atlantic Ocean other than the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, but Atlantis could have been a very flat Island that would not register on sonar equipment. The Atlanteans’ technology could have been so far beyond even ours today that they could protect themselves from the pressure of 4 miles of water on top of them, and their descendants continue to live at least partly beneath the Triangle. Their civilization could have the power to disrupt the electromagnetic field, sink ships, down aircraft, and salvage sunken wreckage.