10 Salton Sea

The Salton Sea in Southern California was never meant to exist. Before 1905, California’s largest lake was not a lake, but rather the Salton Depression, a dry lake bed reaching as low as 85 meters (278 ft) below sea level. That year, work began on diverting the Colorado River in order to irrigate California’s Imperial Valley. The river was successfully diverted, albeit not in the intended direction. By the time the problem was corrected in 1907, the Salton Sea had been filled. Salton’s waters would have evaporated long ago if not for Congress designating the lake as a repository for agricultural wastewater in 1928. This waste, pumped back from the Imperial Valley, has maintained the Sea’s water levels. The Salton Sea still serves as an agricultural wastewater repository as well as a place for recreation and fishing. Despite the constant inflow of wastewater, the Salton Sea is still evaporating. This evaporation sends the matter at the bottom of the lake into the air as very small (less than 10 microns in width) dust particles. More and more of the lakebed is projected to be exposed as time goes on. The Imperial Valley already has a childhood asthma rate three times greater than California’s average; the pollutants from Salton’s bottom will not help.

9 Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania

Mount Carmel is a small town of approximately 6,000 people located 140 kilometers (87 mi) northwest of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal mining region. A typical small town, Mount Carmel is similar to neighboring communities such as Ashland. It once had another very similar neighbor: Centralia. Centralia is a well-known disaster area. A garbage fire meant to clean the town up before Memorial Day in 1962 spread into coal tunnels beneath the ground. This underground fire still burns today and will do so for centuries. The town now stands abandoned with the few remaining structures condemned. Visitors to the site face the danger of sinkholes and toxic gases. That may not be the end of the story. Many coal mining tunnels run underneath the area. Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Resources discovered maps of these systems indicating that the fire could eventually spread to the tunnels under Mount Carmel. These maps were not made public until a right-to-know law was put into effect in 2009. Though it could take decades for the underground fire to reach Mount Carmel, the results are not likely to be pleasant.

8 National Bio And Agro-Defense Facility

Under construction in Manhattan, Kansas, the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility will replace New York’s aging Plum Island Animal Disease Research Facility. The NBAF will continue and advance Plum Island’s purpose of researching pathogens that may pose a threat to animals, specifically those that affect agricultural interests. The knowledge gleaned from this research may be critical in curbing future threats to livestock, both natural and man-made. A disease of particular research interest is foot-and-mouth disease, a virus that could result in a massive loss of livestock if an outbreak were to occur. Constructing a facility which will house and work with foot-and-mouth disease in the middle of American farmland is an arguably questionable decision. In 2010, a risk assessment by the Department of Homeland Security found that there was a 70 percent chance that the disease would be accidentally released from the facility, resulting in an economic loss of $9 billion to $50 billion. The National Research Council then evaluated this report and determined that the risk of an outbreak was underestimated. An updated risk assessment released in 2012 found a much lower risk of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak. However, the NRC concluded that this report used questionable methodology, artificially lowering the risk estimates.

7 Berkeley Pit

In the late 19th century, the advent of electricity brought with it a rise in demand for copper. This was good news for Butte, Montana, near which a massive copper deposit had been recently discovered. Mining commenced, with Butte supplying one-third of the United States’ copper for decades. Underground mining transitioned to open pit mining in 1955 and continued until 1982. By that time, the Berkeley Pit required pumps to keep groundwater from entering the 2-kilometer-wide (1.2 mi) and 542-meter-deep (1,780 ft) quarry. With the cessation of mining, the pumps were stopped, and water began to fill the pit. Today, the water is over 300 meters (1,000 ft) deep. One night in 1995, a flock of snow geese landed in the Pit’s waters. The next morning, 342 dead geese were left floating, their bodies stained orange-brown from the water. The company in charge of Berkeley Pit claimed their deaths were caused by an aspergillosis infection. The State of Montana ruled out aspergillosis, but found burns from copper, cadmium, and arsenic. The findings make perfect sense; Berkeley Pit’s waters are extremely contaminated with high levels of the chemicals above as well as aluminum, cobalt, iron, and zinc. The water has a pH of 2.6, roughly equal to lemon juice. The area around the pit stinks of sulfur. Berkeley Pit is expected to continue to flood indefinitely. When the water reaches a critical level, the groundwater flow will reverse and contaminate nearby Silver Bow Creek, which leads into the Clarks Fork River. This critical level is expected to be reached in 2023. A treatment plant has been constructed and will begin to pump and treat the pit water at that time. The purification method—treating water with lime—will produce hundreds of tons of toxic sludge per day.

6 El Paso, Texas

El Paso, Texas faces a constant danger of running out of water. This is hardly a surprise for a city in the desert, and efforts to ensure a steady water supply have been ongoing for over a century. The Rio Grande Project of 1905 guaranteed all of the river’s unappropriated water for irrigation purposes. The Elephant Butte Dam, constructed north of the city in New Mexico in 1916, stores a great deal of water. There are also two underground aquifers from which El Paso draws its water. Nevertheless, droughts make the Rio Grande as well as its inflow into Elephant Butte unreliable. By the early 1990s, the city’s aquifers were draining at an alarming rate. Since then, El Paso has become a leader in water conservation and a model for other cities. New sources of usable water have been tapped, including a desalination plant to make more of the aquifers’ water usable. Residents are also actively encouraged to conserve water. Despite the undeniable difference these efforts have made, the fear of El Paso running dry still exists. The city’s conservation efforts are at their limit, leaving only the acquisition of new water sources as an option. Rapid population growth, fueled by the military base Ft. Bliss and emigration from Mexico, is cited as a primary factor in the crisis. While the desert city has generally been lauded for its water conservation, environmental groups have criticized El Paso for not keeping its rapid growth in check. Ranchers along the Rio Grande downstream from El Paso also complain that their livelihoods are threatened by the city’s water demand, which can leave little water for their crops and livestock.

5 Asse II Mine

Asse II, near Braunschweig, Germany, was originally a salt mine. The mine’s lack of profitability led to its cheap sale to the German government, which repurposed the abandoned mine in 1967 into a temporary storage site for medium-level radioactive waste. The belief at the time was that rock salt pits were geologically optimal for the storage of discarded nuclear material. The temporary storage site became permanent, and over 100,000 barrels of waste were deposited in Asse II until 1978 . The mine, however, wasn’t as stable as predicted. Cracks formed in Asse II’s walls, allowing groundwater to seep in and dissolve rock salt. Radioactively contaminated brine was first detected leaking from the cracks in 1988, but this wasn’t revealed to the public until 2008. Residents today fear that Asse II will flood, leading to contamination of the region’s groundwater. The current stopgap measure to prevent disaster is pumping 12,000 liters (3,170 gal) of salt water out of the mine per day before it can mix with the radioactive waste, but this is not viable as a long-term solution. Plans are underway to remove as much of the waste as possible by using remotely operated vehicles. An obstacle to this plan is poor record-keeping, meaning that no one knows what some of the barrels contain. Additional issues include cracks in Asse II’s pillars and the problem of where to store the waste once it is extracted.

4 San Francisco, California

It’s no secret that San Francisco, like much of California, is prone to earthquakes. Memories of 1989’s 6.9-magnitude earthquake as well as the even more devastating 7.8 quake of 1906 stand as stark reminders of this fact. Major earthquakes in San Francisco carry with them a risk of liquefaction, which occurs when watery soil essentially turns to liquid as a result of the vibrations, causing structures above to sink or collapse. The geology of the Bay Area is such that much of the coastline—and large parts of San Francisco—are at a high risk for experiencing liquefaction should another major earthquake occur. The possibility of such an earthquake is often placed in terms of “when,” not, “if.” The US Geological Survey states that there is a 63 percent probability that a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake will occur in San Francisco by 2038. Though local residents are conscious of the risk, San Francisco remains a high-demand place to buy property. While the question of liquefaction zones is frequently brought up with local realtors, the desirability of the neighborhood still tends to be the deciding factor for buyers. Companies such as Yahoo, Yelp, and Pinterest have offices in the South of Market (SoMa) neighborhood, one of the biggest high-risk liquefaction zones.

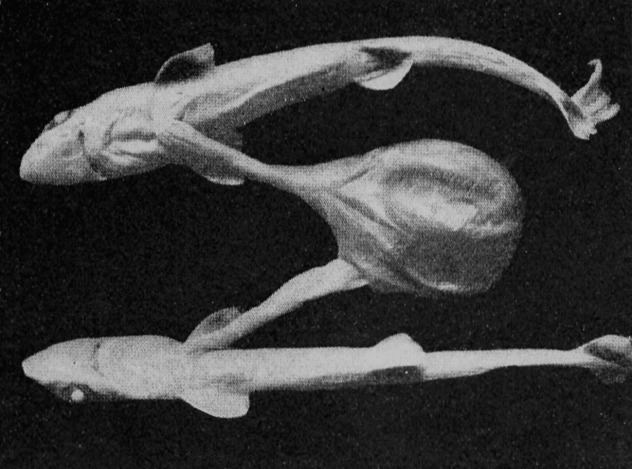

3 Sellafield

Sellafield is a nuclear plant on the coast of the Irish Sea in northwestern England originally tasked with producing plutonium for military purposes, and later with producing electricity for commercial use. Though now decommissioned, Sellafield has been releasing radioactive waste into the Irish Sea since 1952. The body of water is now considered one of the most radioactive on Earth. Mutated fish are caught from the Irish Sea. Mist from its waves dries into radioactive dust. It could get much worse. Sellafield stores its high-level nuclear waste in 21 steel tanks. These tanks need to be replaced because of corrosion in certain components. The waste inside is radioactive enough to produce its own heat, requiring the tanks to be constantly cooled. If the cooling system were to fail, the liquid in the tanks would boil within 12 hours and release radioactivity into the area. Such a failure occurred in 2009, but cooling was luckily restored in only eight hours. The tanks at Sellafield contain 70 times the amount of cesium-137 that was released during the Chernobyl incident. If 10 percent of it were released, Norway would receive 50 times the contamination it received from Chernobyl. The worst-case scenario—the tanks exploding—would require the evacuation of everywhere between Glasgow and Liverpool and could kill up to two million people.

2 Bangkok, Thailand

Bangkok, Thailand is besieged by water. The most obvious culprit, global warming, is projected to raise sea levels by as much as 29 centimeters (11 in) by 2050, resulting in a four-fold increase in the city’s flooding risk. On top of that, or perhaps as a result, the ocean has been eroding the region’s shores at an alarming rate, with some areas expected to see the coastline travel several hundred meters inland in the next six years. To make matters worse, Bangkok is sinking, fueled by land subsidence due to the pumping of groundwater. For years, groundwater has been pumped from below the capital to meet the needs of residents and factories. By the 1970s, the city was sinking 10 centimeters (4 in) per year. Measures to curb groundwater use greatly reduced the sinking to below a centimeter (0.4 in) per year, but more recently the rate has begun to increase, with Bangkok sinking as much as 3 centimeters (1.2 in) per year. The general consensus among scientists studying the problem is that there is no remedy. Bangkok will inevitably sink underwater in the future. The best solution may be simply to rebuild the city on higher ground.

1 West Lake And Bridgeton Landfills

Combine Centralia with Asse II and you have the West Lake and Bridgeton landfills in northern St. Louis. In the 1970s, West Lake Landfill became the burial site for waste left over from the manufacturing of nuclear weapons. The US Environmental Protection Agency reports that the waste stored at West Lake is secure and poses no radiation danger to surrounding areas. No radiation stronger than background levels is detectable in or around the landfill, and an underground wall separates West Lake from its neighboring landfill, Bridgeton. However, a 2013 study by Washington University concludes that West Lake’s danger is understated. Specifically, radioactive material could eventually contaminate the groundwater beneath the site. This water would reach the Missouri River and eventually the Mississippi River, which is a source of drinking water. Next door, the Bridgeton Sanitary Landfill has a problem of its own: A fire is burning underground. This fire is moving toward West Lake. The underground wall separating the two landfills will not stop the fire. It may take over a decade for Bridgeton’s fire to reach West Lake, but should it eventually reach the radioactive waste, an explosion is possible. Essentially a large dirty bomb, this explosion would release a cloud of radioactive gas into the area and cause a severe disaster. Anthony wonders if he should invest in gas masks and water filters.