10Living Worm Towers

Unlike most of our list, the nematode Pristionchus pacificus isn’t technically parasitic at all. Sure, it has all the trappings of a parasite—it lives in the body of a dung beetle, resists the insect’s immune system, and depends upon its body for both a food source and a breeding ground. It just doesn’t really qualify as parasitic because it doesn’t actually begin feeding until after the host is already dead. It waits around like an internal vulture until its chosen beetle winds down and begins to decompose. The bacterial explosion in the beetle’s corpse will be the worm’s food source, and it will also mate and produce thousands of young from within the rotting husk. Even more unsettling is how these worms actually get into their hosts to begin with. As larvae, hundreds of them will converge and “glue” themselves together into a single, squirming “worm tower,” which waits for a beetle to pass overhead. It’s one big worm made out of other worms, one of the only structures of its kind in nature.

9The Jellyfish That Evolved Into A Disease

We can forgive biologists of the past for confusing Myxozoa, or “slime animals,” with protozoans. They are, after all, single-celled microorganisms that grow in a slimy, infectious film on the tissues of fish, including many important commercial species. Different varieties of Myxozoa attack different organs, such as the heart, lungs, brain, or spinal tissues, and the infected can have a mortality rate of up to 90 percent. Shockingly, genetic sequencing eventually proved that this “disease” not only belonged in the animal kingdom, but it belonged to the same group of animals as corals, anemones, and jellyfish. The cells even possess structures identical to the microscopic stingers found in jellyfish tentacles, though in this case, they’re used to inject an infectious, amoebic stage of the parasite rather than venom.

8Enteroxenos—The Worm That Isn’t A Worm

Enteroxenos is a parasite found in the digestive tract of the humble sea cucumber. The colorless, tangled noodle consists almost entirely of reproductive organs in a repeating chain, spewing thousands of eggs out of its host’s anus and absorbing the cucumber’s pre-digested nutrients through its outer skin. As far as parasitic worms go, it might seem fairly ordinary—it’s actually identical to a common tapeworm in almost every respect. The surprising difference, however, is that this animal has no relation to anything else that we call a “worm.” Its true nature becomes apparent only during its larval stage. Enteroxenos‘s swimming, planktonic larval form closely resembles that of an ordinary sea snail, because that’s exactly what this animal is—a snail. Once it finds the rear end of a sea cucumber, it squeezes inside and begins its metamorphosis, losing its shell, its snaily foot, its face, its non-reproductive organs, and every other trace of normal snail or slug anatomy. It’s like a human growing up into nothing but a big clump of genitals so that it can live in something else’s stomach and keep mating with itself.

7Glow Worms Of Death

Like the tower-building Pristionchus pacificus, the nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora is more of a semi-parasite. It doesn’t feed directly on the moth caterpillars it infests, but it uses their guts to farm its own symbiotic bacteria, which in turn produce the nutrients it depends upon. These nasty little guys, however, do feed and multiply while the host is still alive, and they eventually become so numerous that the caterpillar festers and dies before it can ever metamorphose into a proper moth. What really sets this parasite apart is the visible effect it has on the host; as the bacteria build up, the caterpillar changes from almost colorless to a pinkish red, and like the bacteria found in deep-sea fish, they also produce light. It’s usually not enough light for the human eye to see, but it’s enough for the caterpillars to stand out to birds and other animals, who quickly learn that the red, glowing bugs taste disgusting. This ensures that many infected insects will belong only to the worms, so far the only known example of a parasite that changes its host’s appearance to ward away its predators.

6Uterine Lice

“Uterine” and “lice” are two words you probably didn’t know you never wanted to hear together, but luckily for us, Trebius shiinoi only infects angel sharks. Unfortunately for them, the flea-like larva of this crustacean seeks out the reproductive canal of a female host, creeps its buggy way through the reproductive canal, attaches itself to the inner lining of the uterus, and remains there permanently. It cements its head in the tissues, loses all of its limbs, and grows into a soft, immobile, worm-like tassel. If the host happens to be pregnant, the bug is also just as likely to latch onto the skin of an unborn pup, but won’t live long once the pup is born. This weirdo is actually only one example of an “anchor worm,” a broad category of parasitic crustaceans who all mature into limbless, worm-like forms embedded in host tissues. Most anchor worms attack the outer skin, which isn’t quite as horrifying, but some specialize in the gills, nostrils, mouth, anus, or even eyeballs of various fish. Some may even live on the outside, but send a bloodsucking tendril all the way to the host’s heart or other vital organs.

5Frog-Mutating Flatworms

It’s understandable to assume that an outbreak of horrendously deformed, multi-legged amphibians has something to do with a nuclear power plant, and news reports once sensationalized these “monster” frogs as products of man-made ecological hazards. The true culprit is something far more natural, but ultimately far weirder, more disturbing, and arguably more sinister than mere carelessness and waste. Parasitic flatworms of the genus Ribeiroia infect amphibians during the tadpole stage, drilling themselves into the tissues that will eventually form into the adult frog’s legs. The presence of the parasitic larvae causes limb development to go horribly awry, often resulting in a tangle of misshapen, extraneous legs. The monstrous frog’s ability to jump and swim are significantly impaired, and that makes them much easier targets for hungry shorebirds. In the stomach of a heron, the parasite completes its life cycle, and the bird’s droppings will spread its eggs to other bodies of water.

4Wasp-Eating Wasps

Everyone’s probably familiar by now with parasitoid wasps, which spend their larval stages in the bodies of other insects before chewing their way out like the creatures in Alien. Members of the genus Trigonalidae, however, add a weirder twist to this lifestyle—rather than injecting a few eggs directly into insect hosts, they embed hundreds of them in the edges of leaves, hoping that they’ll be ingested by caterpillars. Once inside, the trigonalid larvae begin hunting for their only food source, the larvae of other parasitic wasps, which they tear apart with a set of formidable mandibles. Despite said mandibles, they’ll never even attempt to feed on the caterpillar itself, and the vast majority of the poor babies are doomed to starve when they end up in a host devoid of any other parasites. This is why the mother wasp lays so many eggs and just leaves them on plant life; it expends energy to find caterpillars and squirt eggs through their skin, so she instead uses that energy to produce a huge number of young and let luck do the rest. Unfortunately, once the trigonalids are done clearing a host of weaker wasplings, they’ll still have to break back out of its body.

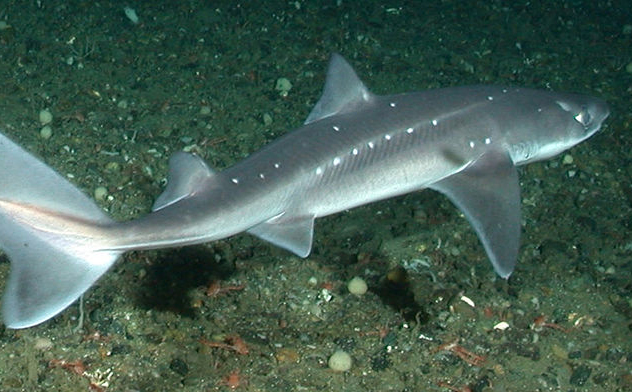

3Shark-Neutering Barnacle

It’s extremely common for the parasites of invertebrates—such as insects and mollusks—to castrate their hosts, but Anelasma squalicola is one of the very, very few known to castrate one of us vertebrates. It’s another species of crustacean, and the victim is another small shark. The parasite is similar in most respects to any other barnacle, but it buries most of its body right into the back of a small dogfish, sending a series of “roots” past the animal’s spine to sap nutrients from its internal tissues. Despite being nowhere near the shark’s genitalia, it somehow hinders their development to the point of uselessness, and it’s not entirely clear why. Mating and producing young expends a great deal of nutrients, so for other parasites, castrating the host means more resources for themselves and their own babies, but we still know very little about this barnacle’s reproductive behavior. They have been found to group together in clusters, so it’s possible that they mate the same way as similar, non-parasitic barnacles, groping each other with long, prehensile penises and spurting young into the surrounding water.

2Face-Biting Clam

A surprising number of freshwater mussels actually begin their life in a tiny parasitic stage, riding the bodies of fish to new homes. Mussels employ a variety of weird strategies to get these parasitic larvae, or “glochidia,” into the right host fish, including bizarre, sticky “nets” and complex, appetizing lures packed with young, but the most direct and most violent is the snuffbox mussel, Epioblasma triquetra. The required host is a small fish called a logperch, which tends to root around the river bottom for food. Lined with horrible little teeth, the female snuffbox will clamp her shell down on anything that brushes it—hopefully a logperch’s face—which she will then squirt full of her young. Other tiny fish may set off the trap as well, but few are as tough as the logperch, and often end up with their skulls smashed. Requiring a specific species to complete its development, the killer clam mercilessly weeds out the unsuitable.

1Ant-Foot Mite

The famous tongue-biting louse, Cymothoa exigua, is often said to be one of the only parasites that functionally replaces the body part of another creature. Macrocheles rettenmeyeri is one of the only others, a tiny mite that plugs itself onto the end of an army ant’s leg. There it steadily sucks blood and uses its own legs to grip any surface it’s pressed against. In other words, the ant continues using the parasite as a perfectly good foot, if not an even better one, since it’s a foot with eight smaller feet on it. This is especially important to army ants, who link their feet together to form temporary bridges and nest structures out of their own bodies. The mite just wants to eat—it doesn’t want to actually interrupt any ant business, or its host might not live long enough to keep feeding it. More creepy biology from Jonathan Wojcik at bogleech.com!