10 Dino Bravo

In his day-to-day life, he was known as Adolfo Bresciano, an Italian immigrant in Quebec. When the spotlight was on, he became Dino Bravo, professional wrestler. Dino achieved his greatest success in the late 1980s working with the World Wrestling Federation where he was billed as “Canada’s Strongest Man.” Dino Bravo retired in 1992. Less than one year later, he was dead. His body was found in his home, sitting in front of a hockey game and riddled with 17 bullets. Nobody was ever charged with Dino Bravo’s murder, and the precise circumstances regarding his death remain a mystery to this day. However, wrestlers talk. Rumors soon arose that Bravo was killed by the Mafia due to his involvement in a cigarette smuggling ring. Although there’s no official story regarding Bravo’s death, wrestler and friend Rick Martel gave a detailed description of the events in an interview. After retiring from wrestling, Bravo used his family ties to Montreal mobster Vic Cotroni to make some money. Bravo leveraged his fame to secure connections with people who wanted to work with a former wrestling champion. He grew more and more successful until he became responsible for a shipment worth hundreds of thousands of dollars which was picked up by the police. His death was mob retaliation for a deal gone bad.

9 Babes In The Woods Murders

The term “babes in the woods” has been used several times by the media when referring to cases with multiple child victims who were found in the forest. In 1953, it happened in Vancouver when the bodies of two young boys were found in the woods of Stanley Park. To this day, the boys have remained unidentified. A later examination revealed that they were murdered six years prior to their discovery. The remains were so decomposed that the medical examiner originally identified one of the victims as a girl, and it wasn’t until 1998 that DNA testing proved the victims were not only boys but brothers. The police had very little to go on. All they knew was that the victims were white, between seven and 10 years old, and killed with a hatchet left at the scene. Their bodies were arranged in a straight line and were covered with a woman’s rain cape. Both boys were wearing leather aviation helmets. Based on the information they had, police looked for a mother with two young children. They soon heard of a red-haired woman who was picked up by local loggers a few years earlier. She had two children with her, aged 6–7, and at least one of them was wearing an aviation helmet. Eventually, police did uncover a surname—Grant—but the lead went nowhere. The trail went cold after that, and the “Babes in the Woods” murder became one of British Columbia’s most infamous mysteries, immortalized at the Vancouver Police Museum.

8 William Robinson

In 1868, William Robinson, a resident of Salt Spring Island in British Columbia, was found murdered in his home, shot in the back while eating dinner. He was the third victim in less than two years, and all three had one thing in common—they were black. The first two murders are still unsolved, although it was always presumed that the same person was responsible for all three killings. Officially, the murder of William Robinson has been solved for over a century. An aboriginal man named Tshuanhusset was charged with the crime, found guilty, and hanged soon after it was committed. However, modern historians doubt that the right man was punished for the crimes. The biggest problem with the investigation was that it focused entirely on Tshuanhusset even though there were other possible leads. And there was no effort to connect him to the previous murders to show whether the same person truly committed all the crimes. Months after Robinson’s murder, another black man named Giles Curtis was killed. If the same person was responsible for all four killings, it couldn’t have been Tshuanhusset. It’s pretty hard to ignore the racial component to the case. Four black men were killed, and an aboriginal was convicted by an all-white jury. A white man was reportedly seen at the first crime scene in 1867 but was never looked into. Even when the navy began investigating after the fourth murder, they only investigated aboriginals and didn’t produce any solid leads. While the history books officially consider William Robinson’s murder solved, it will likely remain a mystery forever.

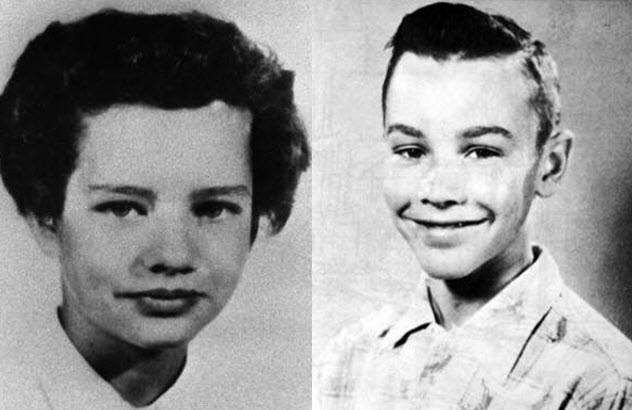

7 Lynne Harper

In 1959, 12-year-old Lynne Harper disappeared near the Canadian Air Force Base in Clinton, Ontario. Two days later, her body was found abandoned on a nearby farm. Police immediately turned their attention to 14-year-old schoolmate Steven Truscott, the last person seen with Lynne. Truscott was charged with the murder and tried as an adult. He was subsequently found guilty and sentenced to death, although the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He spent 10 years in prison before being paroled. In 2007, after a new investigation, Steven Truscott was acquitted of all charges, receiving a big settlement and an apology from the attorney general for the miscarriage of justice. New evidence gathered using modern technology showed that the original investigation likely got the time of death wrong. As part of Truscott’s defense, his lawyers presented several persons of interest who were never seriously investigated for Lynne Harper’s murder. This included a Clinton resident who was a convicted pedophile, a minister with a history of sexual assault, and an electrician working out of the Clinton base with a rape conviction. The goal wasn’t to find the killer. It was to show that the original investigators were wrong to focus all their attention on a 14-year-old when there were plenty of other viable suspects around. One former officer believes Lynne’s death was the work of an identified but unnamed serial killer. He thinks the criminal worked as a traveling salesman and was responsible for several murders throughout Ontario. However, that man, like most other suspects, is dead, which means we’ll probably never find Lynne Harper’s real killer.

6 Louie Sam And James Bell

In 1884, one of the darkest moments in the history of British Columbia took place when an angry American mob crossed the border from Nooksack (today Whatcom County, Washington) and lynched a 14-year-old youth named Louie Sam. Sam was part of the Sto:lo First Nation people and stood accused of murdering a man named James Bell. Believing that he would be treated justly, the Sto:lo turned Sam over to the British Columbian authorities. However, the Canadian police were overpowered by the mob that hanged Louie Sam from a tree north of the border. It soon became apparent that Sam didn’t kill James Bell. Instead, the one or two men who stirred up the mob in the first place were the likely culprit(s). British Columbian authorities sent two officers disguised as laborers into Nooksack to collect information. They came back with statements which seemed to suggest that a man named William Osterman had killed James Bell. He had taken over Bell’s business as a telegraph operator, and he was the one who brought Louie Sam to Nooksack under the pretense of offering him a job. Osterman may have been working with his brother-in-law, David Harkness, who was sleeping with Bell’s estranged wife and was thought to be the ringleader of the mob. Based on testimonies alone, the government of the Washington Territory refused to extradite the men to stand trial in British Columbia. If the story was true, then Osterman and Harkness got away with two murders.

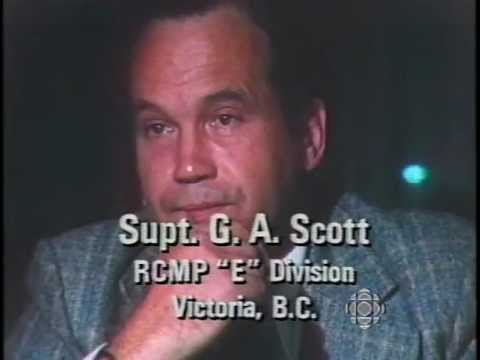

5 Calgary’s Unidentified Serial Killer

Calgary might have a serial killer on its hands. Since the early 1990s, a number of women, many of them prostitutes, were stabbed or beaten to death and left in shallow graves in and around Calgary. It all started with Jennifer Janz, who was found in August 1991 off the Trans-Canada Highway. Two more women were found in the same area over the following months. The next two victims were murdered in 1992 and 1993 and left in fields to the east of Calgary. If there really was one killer, he was active between 1991 and 1993. But it seems that he disappeared afterward. Common theories in these situations say that he died or went to prison on an unrelated charge. But it’s also possible that he simply moved. Edmonton has its own possible serial killer. He has been active since 1997 and could be responsible for upward of a dozen murders. When the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) launched a task force called Project KARE in 2003, he became one of their main targets. But so far, the RCMP has been unable to prove that this killer actually exists. Police now think that the prostitute killings in Edmonton from the late 1990s to the early 2000s could be tied to similar murders in the city in the late 1980s. Not only that but they’ve also looked into some of the Calgary killings to find a possible connection. They are not ruling out the possibility that one person could be responsible for multiple murders in both cities. Recently, police revealed that a mechanic named Thomas Svekla, the man whom they thought responsible for at least two of the Edmonton murders, has been behind bars since 2006.

4 Peter Verigin

In the early 1900s, a Russian religious group known as Doukhobors immigrated to Canada, settling on land given to them by the Canadian government in Saskatchewan. Pretty soon, a man named Peter Verigin rose through the ranks and became the Doukhobors’ spiritual leader. A preacher by day, Verigin became known as “Lordly” within the Doukhobor community and helped it expand into British Columbia. Verigin was killed in 1924 in a violent train explosion. Although several other people died in the blast, Lordly was always considered the target as the bomb was detonated under his seat. His assassination remains unsolved, although it’s not for lack of suspects. It seems that, at the time, more people wanted Verigin dead than alive. Many Canadians resented the Doukhobors for being exempted from fighting in World War I due to their state-recognized pacifism. Within the Doukhobor community, extremists called the Sons of Freedom accused Lordly of straying from their core beliefs. The Soviets were insulted by the Doukhobors’ refusal to return to Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution. Americans from the KKK and the American Legion wanted to stop the Doukhobors from expanding into the US after Verigin bought land in Oregon. Even Lordly’s own son, Peter Petrovich Verigin, threatened his father for being a liar and a crook who was only interested in young girls. Many Doukhobors believed that the Canadian government was behind Verigin’s assassination. Others entertained the possibility that the explosion was an accident caused by a gas leak. No serious leads were ever found.

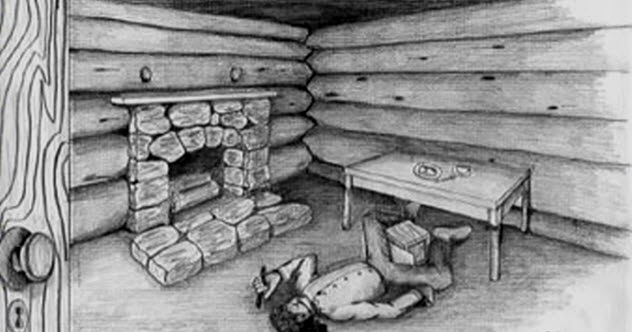

3 Hemlock Valley Murders

In 1995, three murder victims were found in an area near the Agassiz Mountains east of Vancouver: Tammy Pipe, Tracy Olajide, and Victoria Younker. The women were very similar: all prostitutes in their thirties working the Downtown Eastside area of Vancouver. They were all assaulted, murdered, and abandoned in the same area. Police quickly determined that they were looking for one killer, and they had a pretty good idea who it was—Ronald Richard McCauley. McCauley had a history of violent assaults on prostitutes. He had served 17 years for two rapes and two attempted murders and was released in 1994. He did the same thing again in 1995 shortly before the murders started. McCauley was jailed again indefinitely, but police strongly believed that he had escalated his crimes to murder before his imprisonment. They couldn’t prove it, though. Although police had recovered semen samples from the crime scenes, the samples were too degraded to be tested. As technology progressed, forensic techniques improved, and in 2001, police were finally able to test the DNA samples obtained in 1995. They didn’t match Ronald McCauley. Surprised by this outcome, investigators had to look for alternative suspects. The Downtown Eastside area of Vancouver is notorious for drugs and prostitution. It was also the hunting ground for infamous Canadian serial killer Robert Pickton, but he wasn’t investigated because he murdered his victims on his pig farm. There is no shortage of suspects with violent histories against prostitutes, but so far, nobody stands out better than McCauley.

2 Aielah Saric-Auger

Even decades later, the “Highway of Tears” remains a giant black eye for Canadian law enforcement. Ever since 1969, dozens of young women have been abducted and murdered on a stretch of Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia. The police’s big break came in 2012 when DNA evidence linked 1974 victim Colleen MacMillen with US serial killer Bobby Jack Fowler. Fowler was already in prison on a rape and assault charge. He was a transient worker who traveled frequently between the United States and Canada. Police had suspected that he was a serial killer for a while, but until that time, he hadn’t been charged with any murders. Soon enough, Fowler became the primary suspect in several other Highway of Tears killings. There are a few cases where it’s impossible for Bobby Jack Fowler to be the culprit. At least five young women disappeared after he was imprisoned in 1996. Three of them are missing, so they are still investigated as such. One of them, Loren Donn Leslie, was identified as a victim of serial killer Cody Legebokoff, who was active around the city of Prince George. That only leaves one—14-year-old Aielah Saric-Auger. Aielah disappeared in February 2006, and her body was found a few days later off Highway 16 near Tabor Mountain. Like many victims on the Highway of Tears, Aielah was aboriginal. Accusations of incompetence, racism, and cover-ups have dogged the investigations into the murdered and missing women for a long time. Activists are still lobbying for a task force to look into the cases of Aielah and seven other native women missing since 1990 for links that might reveal a common culprit.

1 Julia Johnson

On April 25, 1928, five-year-old Julia Johnson mysteriously disappeared from outside her home in Winnipeg. Several neighbors saw her prior to that, allowing police to later establish a detailed timeline. At around 2:00 PM, Nathan Taplinsky, the blacksmith across the street, saw her playing with other children. At 3:50 PM, neighbor Pauline Kral looked out the window and spoke to Julia, who asked when Mrs. Kral’s daughter Elizabeth would be coming home. That was the last time anyone saw Julia Johnson. Just five minutes later, Mrs. Kral’s son walked in and inquired about Julia as her mother was out looking for her. Pretty soon, the entire neighborhood had formed a search party. The police were called in, but it was in vain. Julia wouldn’t be found for almost nine years. In 1937, a disused building near the Johnsons’ home was being repurposed and a machinist was busy dismantling the old boiler in the basement. Inside the boiler, the worker found the body of Julia Johnson, mummified in ash. There wasn’t much evidence left, and the coroner couldn’t even establish if Julia had been murdered or if her death had been an accident and someone had hidden the body. Prior to the discovery, police only had one solid lead—a neighbor with a criminal record. After being questioned, he faked his death and tried to escape to Seattle. He was arrested in Washington and deported to Canada where he was questioned again. But he disappeared once more, this time permanently. After Julia’s body was found, police tried to figure out who had had access to the building on the day in question. Building manager John Goodwin claimed he had left a key at the blacksmith shop so that prospective tenants and meter readers could enter the building. Hydro meter reader William Clark backed up this claim. However, both blacksmiths denied this. Somebody was lying, but police were never able to prove who.