We’ve all heard Dr. King’s speeches, but his life story is usually left on the cutting room floor. That story, though, is every bit as important. It shows why he became the man he was and gives us a glimpse into the world as it was before he changed it.

10 His Grandfather Accepted Being Cheated

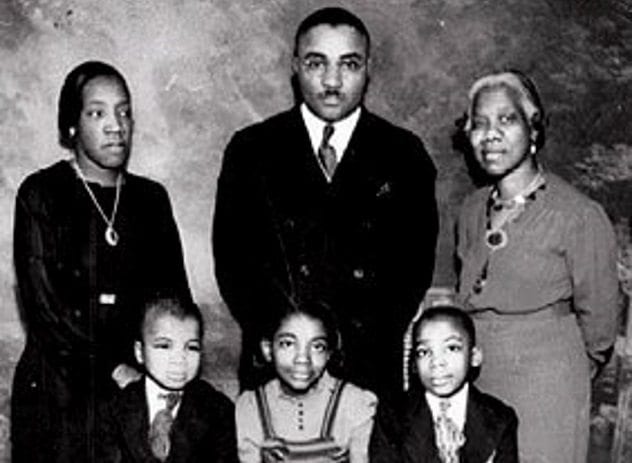

King’s father, Martin Luther King Sr., played a huge role in who he grew up to be. His father’s life began on a plantation, where King Jr.’s grandfather worked as a farmhand. They were treated as second-class citizens—and King Sr. was told to accept it. However, King Sr. had a hard time living as a lesser class of human being. When he was little, he caught the white plantation boss cheating his father out of the money he’d worked so hard to earn. King Sr. called him out on it, but it didn’t do him any good. The boss said, “Jim, if you don’t keep this nigger boy of yours in his place, I am going to slap him down.” His father, too afraid of losing his job to speak out, told King Sr. to be quiet and went home without pay. King Sr. left the farm when his father, in a drunken stupor, nearly beat his mother to death. The boy had to wrestle his own father to keep him from killing her. Afterward, he fled town and went to Atlanta, where he would become a preacher and start his family. For the rest of his life, he vowed, “I ain’t going to plough a mule anymore,” and he held his son to the same promise.

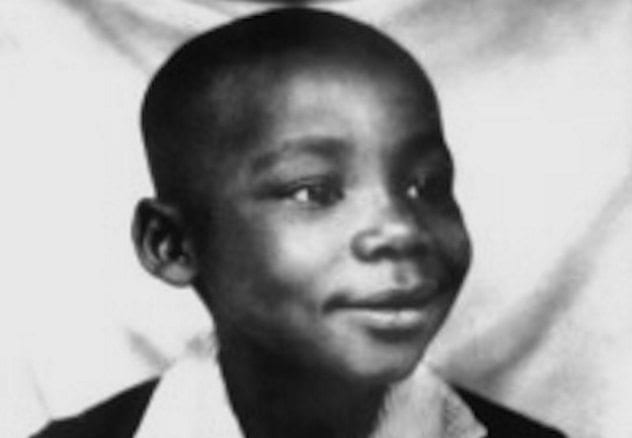

9 He Wasn’t Allowed To Be Friends With A White Boy

From the time he was three years old, King Jr.’s best friend was a white boy whose father owned the store across the street from his home. When they were preschoolers, they would play every day and treated each other as equals. When they started school, though, they drifted apart. They couldn’t study in the same building; King had to study in a school for blacks, and his friend studied in one for whites. The boy didn’t come around often anymore. Then, when he was six years old, the boy informed King that his father wouldn’t let them play together anymore. “For the first time, I was made aware of the existence of a race problem,” King would later recall. He hadn’t thought of himself as different until that moment—but now he knew how he was seen. For a long time, the experience filled him with hate. “From that moment on,” King said, “I was determined to hate every white person.”

8 His Father Beat Him Horribly

King’s friends told him, “I’m scared to death of your dad.” And there was a reason for it. Both at home and at work, Martin Luther King Sr. was a stern man. He was a preacher, but he didn’t always follow Jesus’s methods. During one service, he threatened to collapse a chair over the head of a congregation member if he didn’t calm down—and that was a story he bragged about. At home, he was even worse. He would beat Martin and his brother, Alfred, senseless for any infraction, usually with a belt. Sometimes, the beatings got out of hand. On one occasion, a neighbor heard him through the walls, yelling, “I’ll make something of you, even if I have to beat you to death!” King Jr. took his beatings in silence. “He was the most peculiar child whenever you whipped him,” his father would later say. “He’d stand there, and the tears would run down, and he’d never cry.”

7 He Was Dressed As A Slave For The Premiere Of Gone With The Wind

In 1939, when King was ten years old, he got to perform at the Atlanta premiere of Gone with the Wind. His father had been put in charge of organizing a 60-person choir for the show, and his boy was to be in the choir. They were to sing for an all-white audience, members of a Junior League association that only accepted white people. Before they performed, the choir was put on stage in front of a picture of a plantation and forced to dress up as slaves. The family couldn’t actually go into the theater after performing. They were part of the entertainment, but only whites were allowed inside. They weren’t the only ones banned, either. Even Hattie McDaniel, the black actress who played Mammy in the film, was forbidden from watching it because of the color of her skin.

6 He Attempted Suicide After His Grandmother Died

King’s teachers described him as a moody and withdrawn boy—and they had reason to believe it. By the time King was 13, he’d tried to kill himself twice. His most serious attempt at suicide came when his grandmother, Jennie Parks, died. She had been a major presence in their home and had helped raise the kids. She had especially doted on little Martin. King would later say, “I sometimes think I was her favorite grandchild.” He was supposed to be with her on the day she died, but he sneaked out of the house. A parade was in town, and the curious boy ran to see it. While he was out, his grandmother had a heart attack and died. King blamed himself. He believed it was his fault that she had the heart attack. Filled with remorse, he climbed up to the top floor of his home and leaped out of the window. He survived, but it took him a long time to recover. His father, telling the story, would say, “He cried off and on for days afterward, and was unable to sleep at night.”

5 His Father Couldn’t Accept Living With Jim Crow Laws

King Sr. was also a civil rights activist. He was the president of the NAACP in Atlanta and a ferocious fighter who managed to erode some Jim Crow laws on his own. And he was a man who never accepted being treated as a lesser person. King Sr. talked back to every white person he saw. When a shoe store clerk asked them to sit the back, he stormed out, refusing to buy anything. He refused to ride the bus because of how blacks were treated on them. He took some major risks with it. One time, when he was pulled over by a police officer for running a stop sign, the officer called him “boy.” King Sr. wouldn’t stand for it. “Let me make it clear,” he told the officer. “You aren’t talking to a boy. If you persist in referring to me as a boy, I will be forced to act as if I don’t hear a word you’re saying.” A black man back-talking a police officer in those days was risking his life. King Sr. was lucky, though: The officer just gave him a ticket and let him go. “I don’t care how long I have to live with this system,” King Sr. told his son, “I will never accept it.”

4 After His First Speech, He Had To Stand On A Bus For Hours

King Jr., though, was young. He didn’t have the luxury of being as bold as his father. “I wouldn’t dare retaliate when a white person was involved,” King said. He was eight years old the first time he faced such a scenario. He accidentally stepped on a woman’s foot, and she slapped in the face and called him a “nigger.” King didn’t do anything; he was eight years old, and she was white. His childhood would be full of worse moments. He watched the Ku Klux Klan beat a man in front of him. He watched the police beat a black man senseless. And he saw more than one black body hanging from a tree. But the moment that made him, in his words, “the angriest I have ever been in my life” came when he was 13. As part of a competition, he delivered a speech entitled The Negro and the Constitution and then hopped on the bus for the 145-kilometer (90 mi) trip home. When white people boarded, he was asked to give up his seat and stand. King hesitated, which got him cursed out by the bus driver. So he gave up his spot and stood the whole way home while the white passengers sat.

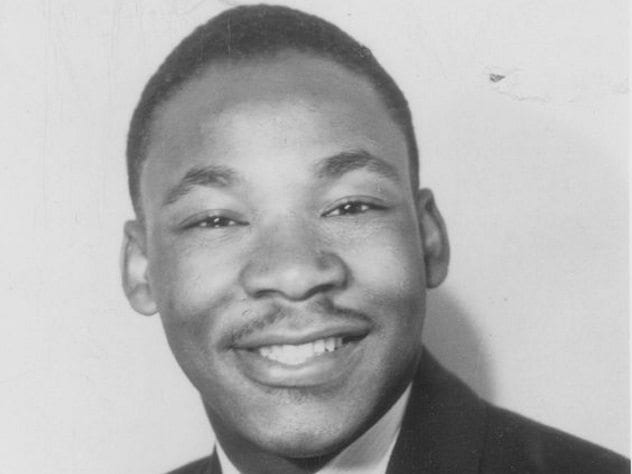

3 He Was Embarrassed By His Father’s Church

By the time he was a teenager, King felt humiliated by his father’s preaching style. His father led a Southern Baptist church, filled with whooping and clapping, which he felt fed into the minstrel caricatures that white people saw in them. He started resisting it. At the age of 13, he argued with his Sunday school teacher, insisting that Jesus couldn’t really have come back from the dead. “None of my teachers ever doubted the infallibility of the scriptures,” King said. “Doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly.” He joined the church because the rest of his family did, but he lived with a lot of religious doubt. He even surprised himself when he went on to become a reverend. He did it, though, because he thought it was the best way for him to talk about social issues. King pledged to be a “rational” minister, one who would be “a respectable force for ideas, even social protest.”

2 He Nearly Married A White Woman

During summers, King worked on a plantation to earn some extra money for college, despite his father’s protests. It was an integrated workforce, and here, working alongside white people for the first time, his hatred started to calm down. “Here I saw economic injustice firsthand,” King later wrote, “and realized that the poor white was exploited just as much as the Negro.” His dream of an integrated world was born in those fields. He nearly married a white woman. She was a cafeteria worker at his school, the daughter of German immigrants, and King swept off her feet. King was in love, and he told all of his friends that he was going to marry her. They were outraged. They insisted it was a mistake, that whites and blacks both would be furious, and that his shot at being a pastor would be ruined. His family wouldn’t accept it, either. They told him that he needed to find and marry a nice black woman and keep things calm. King’s family made him call it off. King told a friend that he could brave his father’s fury but “not his mother’s pain.” After six months together, he broke it off. According to a friend, “He never recovered.”

1 He Experienced Equality For The First Time When He Was 15

Martin Luther King skipped two grades in school. He was only 15 years old when he got accepted into Morehouse University and started his path toward becoming the reverend we remember. His family, however, didn’t have enough money to pay for his education, so he took a job on a plantation in Connecticut. This plantation worked with Morehouse. The school sent them black workers, and in exchange, they sent the school money. The work there was hard. The boys had to work from 7:00 AM to 5:00 PM and had curfew at 10:00 PM, but for a group of black Southern boys, this was the most freedom they’d ever had. The plantation was called “the promised land” by those who worked there, simply because they had the freedom to go into town on weekends. “I never thought that a person of my race could eat anywhere,” King wrote his mother in an excited letter home, “but we ate in one of the finest restaurants in Hartford.” King got to choose his seat on the train ride back—until they made it to Washington, DC, and he was told that if he wanted to go on to Atlanta, he would have to move to the all-black car. For the first time, though, King knew what equality felt like. “It was a bitter feeling going back to segregation,” he wrote. “The very idea of separation did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.” Read More: Wordpress