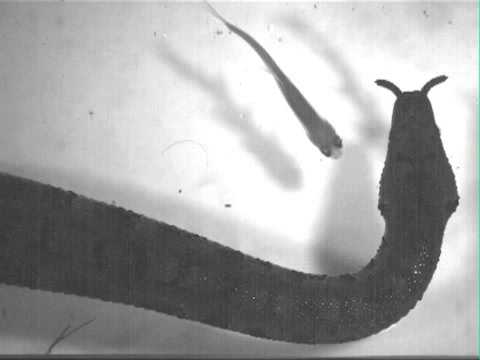

Found in Mexico and Central America, this snake belongs to the pitviper subfamily, and is closely related to the cottonmouth and copperhead vipers from the southern United States. They are highly venomous; their bite causes necrosis, hemorrhage and even renal failure; victims who don’t receive any medical attention after a cantil bite are likely to die in a few hours. But these pit vipers prefer to save their venom for their prey. They feed on any small animal they can catch, from birds and frogs to lizards and small mammals. Unlike fast-moving elapids such as cobras and mambas, the Cantil has a short, heavy body and can’t chase quickly after prey. Instead, it uses a clever trick to lure their victims into attack range. Its tail has a bright yellow or whitish tip, and the snake can move its tail so that it resembles a wriggling worm. Since many of its favorite prey feed on worms, they are tricked into approaching or even attacking the lure, and then the snake can strike and inject its deadly venom on the unsuspecting would-be predator. Although Cantil vipers are not the only snakes that use their tail to trick prey, they are possibly the best known for it. Because of their yellow or white tail, in some parts of Mexico and Central America these snakes are often called “rabo de hueso”, which means “bone tail”, because, since the rest of the snake’s body is dark colored, it looks as if the tail had been stripped of its skin. Other snakes known to use the same hunting technique, called “caudal luring” by scientists, are the North American copperhead, the Australian death adder and the Dumeril boa from Madagascar.

This infamous predator is the largest freshwater turtle in North America; it can weigh up to 100 kgs or more, and lives in southern US lakes, rivers and swamps. Although armed with powerful jaws and sharp claws, the alligator snapper is still a turtle, after all, and can’t chase after prey at high speed. Instead, it uses a hunting technique very similar to that of the Cantil pit viper. It lies motionless in the water, looking very much like a harmless rock, with its jaws wide open. Its tongue has a fleshy appendage that looks much like a worm, and the turtle can move this appendage to make it even more worm-like. Small fish, frogs and even other turtles are often fooled into believing that they found dinner, but as soon as they enter the gator snapper’s jaws to attack the worm, the turtle closes its mouth with tremendous force, instantly killing its prey. This clever technique works best during day, when prey can clearly see the fake worm. At night, the turtle actively walks on the lake or river bottom, feeding on whatever slow moving or dead animal it can find.

Wobbegongs are among the strangest, most fascinating sharks. They are most commonly seen in Australia, which is where they got their name (meaning “shaggy beard” in the Australian aboriginal language). These sharks are slow moving and don’t chase after prey. Instead, they stay motionless in the sea bottom, relying on camouflage to hide themselves from both potential prey and predators. The strange, fleshy appendages around the Wobbegong’s mouth serve a double purpose; to break up the shark’s silhouette, thus improving its camouflage, and to lure small fish and other animals into the shark’s reach. One Wobbegong species, however, uses a more active luring technique. In fact, it is the same technique used by the Cantil pit viper. By flicking its tail, the Tasseled Wobbegong tricks smaller fish into its attack range. Being extremely flexible, the Wobbegong can easily turn around in a fraction of a second and devour any fish that tries to take a closer look at its tail. The Tasseled Wobbegong’s tail even has a slightly forked tip and a dark spot resembling an eye, to make the lure even more fish-like. Although the largest Wobbegong species can grow up to 3.5 meters long, they don’t see humans as prey and will only bite if harassed.

Anglerfish are deep-water fish, widely known because of their monstrous appearance and freaky reproductive habits. They are also the most famous of all lure-using predators. Interestingly, only the females have lures; these are actually modified dorsal spines which protrude above the fish’s mouth like a fishing pole. At the tip of the spine there is a bulb-like organ which contains luminous bacteria, producing a blue-green glow similar to that of a firefly. Because the anglerfish’s skin absorbs blue light instead of reflecting it, the lure is the only thing other deep sea creatures can see; the predator remains invisible in the darkness. When a hapless fish or invertebrate approaches the lure, the anglerfish swallows it whole. Its stomach and bones are very flexible allowing the fish to devour prey up to twice its own size!

Already mentioned in the 10 Unusual and Amazing Snakes list, the tentacled snake is found in South Eastern Asia and is a fully aquatic species that feeds mostly on fish. Its most notable feature are the strange fleshy tentacles on its snout. These tentacles are actually highly sensitive mechanosensors, which allow the snake to detect movement in the water and strike at any unfortunate fish that swims nearby. Another interesting trait is the tentacled snake’s incredible attack speed; it takes only 15 milliseconds for the snake to capture its prey. But fish have incredible reflexes and a fast strike is not enough sometimes, so the tentacled snake uses a clever trick to make fish swim towards danger. When the fish approaches, the snake slightly ripples its body towards it. The fish immediately darts in the opposite direction… but this is what the tentacled snake expects, so it angles its head so that the fish swims directly into its waiting jaws.

Cantil vipers, gator snappers and wobbegongs all have fake lures evolved from their own body parts. The Green Heron, however, manages to lure fish into attack range without this advantage. How? Well, it uses bait. Indeed, green herons have been known to drop small objects onto the surface of water. Small fish are tricked into investigating the object, hoping it may be something edible, and then the heron quickly snatches the unsuspecting victim. Not all Green Herons use this technique, but those who do become quite talented, and they even experiment with different kinds of bait. Some herons have been seen stealing the bread that people feeds to ducks in ponds, and using the bread as bait. Other herons have been known to capture small fish but instead of eating them, they use them as bait for larger fish. No one knows how Green Herons learnt to fish with bait. Some experts believe they learnt from humans, while others think they learnt by themselves by observing how small fish would investigate any small object or animal that fell to the water. Either way, this behavior is obviously not instinctive, making the Green Heron quite possibly the smartest predator in this list.

Assassin bugs are among the deadliest predatory insects. They are not very fast, but use many different and ingenious techniques to hunt. Some disguise themselves as ants to prey on real ants; others use camouflage to ambush prey. One of the most amazing assassin bugs feeds mostly on spiders. When this bug finds a spider web, it uses its legs to tap into the silk threads, sending vibrations that are very similar to those produced by an insect that has become stuck in the web. The spider senses the vibrations and goes for the attack, only to be ambushed and killed by the assassin bug. It is, really, a cruel way to go. It’s just as if someone knocked on your door and said it’s the pizza delivery guy. You open the door, your mouth watering in anticipation… only to be paralyzed and devoured yourself.

Also known as a coatimundi, this raccoon relative is found in Mexico, Central and South America, with some of them also living in Texas, Arizona and New Mexico in the US. Females and young males live in large groups, while adult males often live alone. They are noted for their intelligence, and although they feed mostly on worms, eggs, fruits and insects, they are armed with large fangs and powerful claws and are very capable of hunting larger animals once in a while. According to some accounts, one of the coati’s favorite meals is the green iguana. These large lizards are often found in trees, so coati “packs” use teamwork to hunt them. Some of the coatis climb trees and scare the iguanas into leaping to the ground, where the other coatis quickly capture them. Unfortunately for the iguanas, they are instinctively programmed to leap to the ground whenever they feel threatened, making the coati’s trick a simple, but very effective one.

Fireflies are not true flies; they belong to the Coeleoptera order, which would make them a kind of beetle. They are well known for their light-producing ability (bioluminescence). Most fireflies use their light to communicate with each other; mostly, to attract a mate. This is the case of the Photinus firefly. Female Photinus have very short wings and can’t fly; males on the other hand can. During mating season, male Photinus fly above the ground emitting flashes to attract females. The females in the ground watch the males and respond with their own flashes. Since each firefly species has a unique flashing pattern, males can easily tell their potential mates from females belonging to another species. At least, most of the time… Enter the Photuris firefly. This creature spies on the females of other species and mimics their flashing patterns to attract unsuspecting males. When the males descend to the ground ready to mate, they are quickly attacked and devoured by the Photuris firefly. Yes; it is even worst than being eaten by a fake pizza delivery guy. By eating the male Photinus, the Photuris firefly (sometimes nicknamed the “femme fatale firefly”) not only gets a good meal, but also protection. The Photinus fireflies have certain chemical substances that protect them from predators such as birds and spiders. The Photuris lacks this chemical defense, but can acquire it by devouring unfortunate Photinus males.

The Ancient Romans believed in a monster called the Crocotta. It was said to be a wolf-like beast, native to India or Ethiopia, with the ability to mimic human speech. When hungry, the Crocotta would hide near human villages or houses, and listen carefully to people’s conversations. Eventually it would learn someone’s name and call that person by his or her name, luring him into the woods and devouring him. Although a cool and frightening concept, the Crocotta was nothing more than an exaggerated version of a real life beast, the hyena, a creature that can indeed make some eerie, human-like sounds, but is completely unable to mimic speech. Today, the spotted hyena’s scientific name (Crocuta crocuta) is a tribute to this legendary monster. There is, however, a certain predator that does mimic the “speech” of its victims to lure them to their doom. It was recently discovered that the Margay, a small arboreal feline from Mexico, Central and South America, has the ability to mimic the calls of baby monkeys in distress. This, of course, attracts worried adult monkeys which can then be attacked and devoured by the Margay. Scientists who witnessed this while doing research in Brazil just couldn’t believe their eyes, but natives were not surprised; they informed the scientists that Margays can also imitate the sounds of other animals, such as the tinamou (a flightless bird) and the agouti (a large rodent). Even more, the natives claim that pumas and jaguars also use vocal mimicry to hunt once in a while. As if that wasn’t enough, people in India and Siberia have often reported that tigers can mimic deer calls to lure the unsuspecting herbivores into an ambush. Although this has yet to be confirmed by science, the Margay is the proof that it is not impossible after all. According to the scientists who witnessed the Margay in action, “cats are known for their physical agility, but this vocal manipulation of prey species indicates a psychological cunning that merits further study”. At least we can be happy that cats have yet to learn how to mimic human speech…

The jaguar is the largest cat in the New World; the largest males can weigh over 160 kgs, being as large as an African lioness and having a much stronger bite. They are not picky about what they eat; anything goes, from turtle eggs to anacondas and caimans, and once in a while (although rarely, compared to other big cats) they have been known to attack humans too. Although this behavior has been reported since 1830 by many different authors (always based on accounts of the natives), it has seemingly never been observed by scientists, and therefore cannot be confirmed as fact.