10The Wild East

Not too long after Columbus discovered America, the Russians began colonizing Siberia. The initial expansion was driven by merchants like the powerful Stroganov family, who were hungry for priceless furs. Their agents were Cossack mercenaries who expanded Russian power with extraordinary cruelty. When the Sakha chief Dzhenik revolted, he was skinned alive and then his baby son was suffocated with the skin. The Aleut Islanders attacked tax collectors in 1764, so the Russians burned 18 villages and massacred hundreds. Germs were even more effective than Russian guns and steel. The isolated Siberians were almost as unprepared for European diseases as their distant cousins in the Americas. In the 17th century, smallpox killed over 50 percent of many Siberian tribes. Among the Sakha and Evenk, the death rate was at least 80 percent. The Aleut population dropped from 20,000 to under 5,000 in less than two generations.

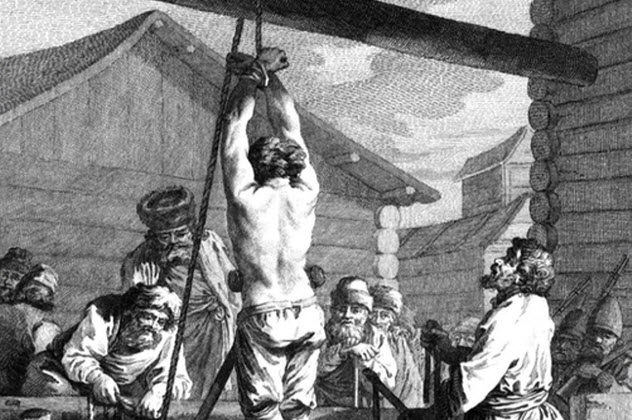

9Torture

The Russian emperors often resorted to cruel tortures to shore up their power. Ivan the Terrible was known for roasting his enemies alive in a giant skillet, which he had made specially. This apparently started a trend since some Cossacks complained in 1640 that a provincial official had been roasting them in huge pans as well as “pulling out their veins.” The Empress Elizabeth was fond of having tongues ripped out with pliers. Peter the Great preferred the knout, a brutal leather whip that sliced 1.3 centimeters (0.5 in) into the flesh with every blow. Peter also personally supervised prisoners being stretched on the rack and burned with hot irons. Under Catherine the Great, rebels were suspended by a metal hook pushed through their ribs and left to die. Others were hanged on rafts, which floated down the Volga as a warning.

8The Court Was Brutally Violent

Theoretically, the Russian tsar was perhaps the most absolute ruler in Europe with the noble boyars as the only real check on his power. In practice, the Russian court tended to be a snake pit, with competing factions often resorting to violence to gain power. As a child, Peter the Great huddled terrified in a corner while armed men rampaged through the palace massacring his mother’s relatives. Ivan the Terrible was sure that boyars had poisoned his mother when he was just eight. They were relatively lucky. Feodor II lasted seven weeks on the throne before he was strangled. Peter III was murdered on the orders of his own wife, who ruled for 30 years as Catherine the Great. Paul I was throttled and kicked to death in his bedroom. One of the assassins then woke up Paul’s son with the words, “Time to grow up. Go and rule!” Little wonder that many tsars became paranoid and cruel. Peter the Great had his own son flogged to death. Ivan the Terrible also killed his son during an argument.

7The Imprisonment Of Ivan VI

Ivan VI became tsar in 1740 when he was just two months old. He was overthrown a year later by his cousin Elizabeth. On her orders, Ivan was placed in solitary confinement at age four. He remained there for 20 years. For most of that time, he was kept in the Schlusselburg Fortress, where nobody even knew who he was. His cell had no windows, so he never saw daylight and “never knew whether it was day or night.” The guards were forbidden to speak to him. His only entertainment was a copy of the Bible. Unsurprisingly, Ivan developed mental problems. He remained locked in his room at Schlusselburg until 1764 when Catherine the Great took pity on him and had him murdered.

6The Oprichniki

After a troubled childhood, Ivan the Terrible became increasingly deranged after a period of illness and the death of his wife. Turning against the powerful boyars, Ivan surrounded himself with a group of mercenaries and commoners who were given land grants around Moscow. These were the notorious Oprichniki, who dressed all in black and carried severed dog heads as a symbol of the fate that awaited traitors. They acted as Ivan’s secret police, torturing and executing anyone suspected of disloyalty to Ivan. In 1570, the Oprichniki stormed into the city of Novgorod and massacred over 10,000 of its citizens. The once mighty trading town never truly recovered.

5Impostors

The Russian Empire was oddly afflicted by impostors, who usually claimed to be a deceased member of the royal family. During the “Time of Troubles” in the early 17th century, no fewer than three impostors emerged and claimed to be Ivan the Terrible’s son Dmitri, who had died as a child. False Dimitri I even managed to be crowned tsar in Moscow, although he was soon murdered. False Dimitri II was essentially impersonating False Dimitri I and gathered a vast Cossack army that ravaged the north. False Dimitri III was called the “Thief of Pskov” after taking that city, but he was defeated and executed in 1612. In the 18th century, the Cossack Pugachev orchestrated a huge revolt by claiming to be the murdered Peter III. Another False Peter turned up in Montenegro, which he ruled for five years until the Ottomans paid a barber to cut his throat. At least three other Russians also claimed to be Peter, including a founder of the Skoptsy sect.

4Cults And Sects

The Russian Church was intense and prone to schism, and it seemed that sects and cults flourished everywhere in the vast Russian Empire. The Khlysty were known for their frantic singing and dancing and were said to wildly whip themselves to show contempt for their physical bodies. The Molokane (“Milk Drinkers”) refused to serve in the military and tried to establish pacifist communes in Siberia. The Doukhobors (“Spirit Wrestlers”) preferred their Living Book of hymns to the Bible. Strangest of all were the Skoptsy, who considered sex the source of all sin and practiced ritual castration and genital mutilation. Male Skoptsy would slice off their testicles and cauterize the wound with a hot iron. Others went further and hacked off their penises as well. Female Skoptsy were expected to slice off their breasts or nipples, and some form of female circumcision was practiced as well. The Skoptsy also castrated their young children, so the sect only survived by converting new recruits. It lasted over a century.

3Self-Immolation

The largest Russian religious split came under Peter the Great, when Patriarch Nikon undertook reforms to bring the Russian church into line with the rest of Eastern Orthodoxy. Among other things, he decreed that the Russians should make the sign of the cross with three fingers instead of two. Led by the Archpriest Avvakum, many Russians refused to accept this. Calling themselves the Old Believers, these traditionalists held services in secret where they crossed themselves with three fingers. The state called them Raskolniki (“Splitters”) and persecuted them relentlessly. Many Old Believers came to believe that the end of the world was at hand. If they suspected they had been discovered, whole villages would gather together, set fire to the church, and burn themselves alive.

2Famines

The Russian Empire was never noted for its efficiency, and its rulers often struggled to respond to the periodic famines that were a feature of life in the provinces. As late as 1891, the tsar responded to widespread crop failures by forbidding newspapers to report on the problem or even use the word “famine.” After much foot-dragging, he eventually banned crop exports and attempted a program of famine relief. As a result, “only” about 400,000 people died in the famine of 1891–92. There were worse examples. In 1601, a volcano erupted in Peru and sparked a series of unusually long winters. The resulting famine killed two million Russians, one-third of the population at the time. The tsar was too busy with a looming civil war to do much. “Dead bodies were found with hay in their mouths, and human flesh was sold in pies in the markets.”

1Serfdom

The Russian Empire was built on the backs of the serfs, who were bound to a particular estate and forced to work for the landowner who controlled it. By the 17th century, landowners were allowed to buy and sell serfs, effectively making them indistinguishable from slaves. Nobles were not technically allowed to kill their serfs, but they could flog or punish them as they saw fit. There were no real consequences if a serf died of his injuries. Landowners could also send their serfs to Siberia or enlist them in the army against their will. Serfdom was abolished in 1861. At that point, Russia had a population of almost 63 million, at least 46 million of them serfs.