In the interest of not seeming to engage in reckless hero worship, we should fully concede to his numerous personal failings, like desiring teenage women or pressuring lovers to get abortions. But for the most part, this list is about the odd aspects of his life and career.

10Surprising Vulgarity

Since Chaplin is mostly remembered today for sentimental comedy, it’s worth noting that when he was first becoming world famous in the 1910s, he was considered beneath middle-class sensibilities. Even the famous stylized walk he did as his Tramp character was characterized as “that nasty little walk” in a 1955 novel about perceptions of Chaplin around 1915. People even thought that Chaplin using a cane despite not needing it was debased because he might have used it to lift someone’s skirt. It didn’t help that, at the time, movies in general were considered a low-class, morally dubious form of entertainment. To be fair, Chaplin did do gags that even today seem a little base, and we’re not just talking about slapstick. For example, in his 1918 film A Dog’s Life, the Tramp’s dog Scraps is digging a hole while the Tramp’s head is near her hind legs. He looks over, gets disgusted by the smell, and lowers the dog’s tail. Even in 1936, by which time Chaplin was in his more respectable period, the Tramp has a scene with a prison chaplain’s wife where he’s audibly trying not to fart and the gurgling of his stomach disturbs her dog. To be fair, such material is part of what made Chaplin’s appeal at the time so universal.

9Blood Test Precedent

In 1942, Chaplin got involved in one of the most scandalous affairs of his life and one of surprising significance. He had a short affair with a woman named Joan Barry while his latest marriage was just ending. Chaplin broke it off quickly. In 1943, though, Barry returned with a claim that Chaplin had fathered a child with her, and a paternity suit followed. At first, Chaplin won the case in 1944, when a blood test showed the child was not his. But during a retrial in 1945, prosecuting attorney Joseph Scott was able to make a case that blood tests were inadmissible evidence. In the face of overwhelming scientific evidence, Chaplin had to pay tens of thousands of dollars in child support. Protests over the case instigated legislation which made sure that blood tests would be valid evidence in future paternity disputes.

8Smuggled Film

Chaplin’s first directorial smash was the 1921 film The Kid. The film has since become largely remembered for the child labor law brought about as a result of Chaplin’s child co-star Jackie Coogan losing most of the money he would have made from the film to his parents. Today, the film might not sit very comfortably with audiences, considering moments such as the Tramp flirting with an angel played by a 12-year-old actress named Lita Grey. (Chaplin would later accidentally impregnate Grey and marry her when she was supposed to star in The Gold Rush as a 15-year-old.) Even the ending—where the Tramp kisses the waif he’s rescued from the dreaded workhouses—might evoke the wrong kind of laughs today. At the time, it was an undisputed monetary success and launched Chaplin’s career in feature-length films. Watch this video on YouTube But one of the more curious things that happened in the production was Chaplin’s smuggling. First, when he finished filming in California and began editing, Chaplin was also beginning divorce proceedings with his first wife, Mildred Harris. Concluding that his wife would want to seize the film he’d spent $500,000 shooting, Chaplin hit on a novel solution: He put the 122,000 meters (400,000 ft) of film in coffee cans, smuggled it to Salt Lake City—where it was beyond the reach of California divorce court—and began cutting the film in a hotel. Later, he had to smuggle the film to New Jersey for its final edit. During his prolonged smuggling operation, Chaplin traveled under an alias, because he was worried the courts would get him sooner or later.

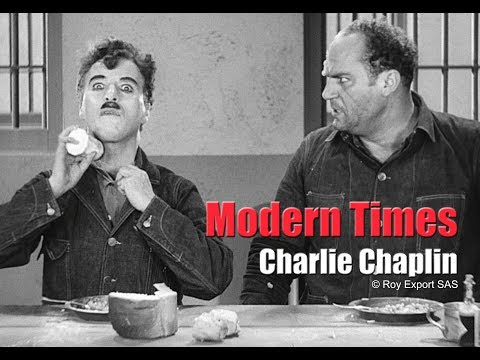

7Sound: Nemesis And Friend

Years after Al Jolson’s 1927 hit The Jazz Singer convinced the film industry that sound was the way of the future, Chaplin stuck to making silent movies. Indeed, such was his disdain for the medium that in the opening of his beloved 1931 film City Lights, he lampooned the whole notion of sound-sync dialogue by having characters speak in kazoo noises. By the time he made his last mostly silent film Modern Times in 1936, he was pretty much the last commercial holdout of his era. In 1942, though, Chaplin apparently became newly enraptured with sound. He took one of his old classics, The Gold Rush, and reedited it to include his own narration. Such was his preference for the version with sound that he didn’t bother to renew the copyright on the silent version, allowing it to lapse into public domain. All of his films after The Great Dictator were notably “talky” and heavily laden with storytelling that emphasized dialogue over visuals. There’s a lesson in that for the artists out there: If you’re the one person sticking to a particular aesthetic belief, you might find you’re denying yourself a lot of possibilities.

6His ‘Best’ Movie

The critical consensus regarding Chaplin’s films says that his silent movies were his best—some of the best of all time, in fact. For example, the American Film Institute’s ranking of the 100 best films of the 20th century puts City Lights at No. 11, The Gold Rush at No. 58, and Modern Times at No. 79. You’d think Chaplin would have considered one of those his best. In fact, Chaplin thought his best movie was one most fans haven’t even heard of: His 1967 film A Countess from Hong Kong—the only color film Chaplin made. Starring Marlon Brando and Sophia Loren, it’s essentially a bedroom farce where Loren plays a Russian lady who is to be forced into prostitution until she finds a way out of it by blackmailing Brando’s character to help her escape to America. Critics and audiences disagreed immensely with Chaplin on the film’s quality, and it became a widely panned flop. The only successful aspect of the film was Petula Clark’s performance of “This is My Song,” which reached the No. 1 spot on the British charts (and was written by Chaplin).

5The ‘Communist’ Kick

Beginning in 1946, Chaplin was under official scrutiny by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on suspicion of being a crypto-communist. So exhaustive was the investigation that the FBI reached out to MI5—their equivalent in the UK—to find evidence of communist sympathies or, failing that, a reason to deport Chaplin. Although MI5 found no such evidence and the FBI itself found no evidence that he was performing espionage or was a danger to American interests, Chaplin was still denied reentry to the US in 1952. In the process of trying to find something to deny Chaplin reentry, something surprisingly banal—even by the notoriously hysterical standards of the Red Scare—was hit upon. In 1917, in his short film The Immigrant, the Tramp is part of a crowd of mistreated immigrants loosely tied to a wall. As an immigration officer walks by, the Tramp kicks him lightly while facing away from him. This was particularly interesting to FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, who used it as a sign that Chaplin was unfit to reside in America more than 30 years later.

4Israel Thornstein: Frenchman

During the aforementioned investigation, a weird rumor about the iconic comedian came to light. Since the 1910s, it had been rumored that Chaplin’s real name was Israel Thornstein and that he was born across the Channel somewhere in France. Of course, evidence of this was nonexistent. However, evidence of something else was also found to be nonexistent: birth records of Chaplin being born in Britain. Indeed, although Chaplin immigrated to the United States in 1910, there weren’t any immigration records found for him prior to 1920. However, that was more likely evidence of the unreliability of record keeping at the time rather than evidence of any deceptions. So why the name Israel Thornstein specifically—one which doesn’t sound the least bit French? It was due to the persistent misconception that Chaplin was a Jew. Notably, Chaplin reacted to the rumor by casting himself as a heroic Jewish barber in The Great Dictator (pictured above). The one time Chaplin played a French person, he was a murderous thief Monsieur Verdoux in the 1947 film of the same name. That might give some indication as to which of those two Chaplin would rather be thought of as.

3Deleted Scenes: The Movie

In 1918, Chaplin decided to end his relationship with Essanay Studios and strike out as an independent filmmaker. Considering that he was still world famous at the time, there was huge demand for more of his films, even though he’d already made dozens of them for the studio by that time. Essanay came up with a terrible solution, decades ahead of its time: They took a bunch of discarded shots and even parts of an unfinished feature-length Chaplin film called Life. They brought in some actors to imitate the famous comedy troupe the “Keystone Cops” for a few connective scenes. The end result was called Triple Trouble. Chaplin was furious that scenes he considered so embarrassingly bad that he’d wanted them destroyed were being screened for the public and denounced the film in the press. Critics, for the most part, agreed with Chaplin, and the film was a bomb. Historians noted that Chaplin listed the film as one of his credits in his 1964 autobiography and took that as evidence that he’d gotten over his grievances. It’s also possible that Chaplin had simply forgotten what Triple Trouble was by then.

2Fake Chaplins

In the late 1910s, a weird minor film genre of “people pretending to be Charlie Chaplin” sprung up. It wasn’t just a matter of people trying to copy his style to promote themselves. These actors would be dressed and made to look as much like Chaplin as possible, and film distributors explicitly said that the actor was Chaplin himself. These performers included Billie Ritchie, Stan Jefferson, and—most notably—Billy West, who did it for years. Critics have said that while West managed to copy most of Chaplin’s mannerisms, the problem was that his movies never tried to do anything to make his bootleg version of the Tramp sympathetic, such as doing any sort of emoting. Instead, he just imitated Chaplin’s gags and walks. Also notable about West was that his antagonist in many of the faux-Chaplin shorts was played by Oliver Hardy (of Laurel and Hardy fame), essentially copying the sort of role that usually went to Eric Campbell in the real Chaplin’s movies.

1Disney’s Savior

One of the more significant ways Chaplin’s influence is felt today is due to his part in the success of the 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. That film was largely responsible for the Walt Disney Company becoming as powerful as it is today. It had a record-breaking gross and was the first hit feature-length animation. However, there was considerable concern that Disney would not be able to pull off a feature-length film. Beyond simply laughing at Mickey Mouse, would audiences be able to empathize with a drawing of Snow White? Would they be scared by spooky drawings of trees? It was going to be a huge gamble for the company. Chaplin and Walt Disney had become friends and business associates by then, and Chaplin was fully encouraging Walt to go ahead with the production. When it was completed, Chaplin assisted Disney’s accountants with his own records from Modern Times, in order to get proper pricing for the film as the company RKO distributed it. Disney was effusive about Chaplin’s assistance, saying that without it they would have been “sheep in a den of wolves.” Perhaps Chaplin would have been a bit more hesitant to aid Disney if he’d known what was coming. Within a decade of Chaplin helping to launch the Disney brand, Disney would be testifying before Congress regarding his belief that there was communist influence in Hollywood. By 1947, Disney would be supporting the sort of blacklist that got Chaplin essentially banished from America. That’s showbiz friendship for you. Dustin Koski is also featured in the Listverse Bathroom Reader.