10 The Sea In The Sky

For this story, we are indebted to English chronicler Gervase of Tilbury and his work Otia Imperiala. Writing around 1212 for his patron, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV, he declared his belief that “the sea is higher than the land,” that it was “above our habitation . . . either in or on the air.” This notion was based on Genesis 1, which speaks of “waters above the firmament.” For proof, Gervase offers an episode that took place in an English village. One overcast Sunday, as the villagers were leaving church, they noticed an anchor hooked to one of the tombstones. It was attached to a rope that was stretched taut upwards to the cloudy skies. To their astonishment, the rope began to move as if someone was attempting to pry the anchor away from the tombstone. The anchor would not budge, and presently, noises like sailors shouting were heard above, and a man began to descend down the rope. The villagers took hold of him, at which point he died, “suffocated by the humidity of our dense air as if he were drowning at sea.” After an hour, the rope was cut from above, and the other sailors sailed away. Another tale concerns a merchant who accidentally dropped his knife while out at sea. At the same hour, the very same knife suddenly fell through an open window of his house in Bristol, dropping onto the table in front of his startled wife. As might be expected, such accounts are interpreted by UFO theorists to be stories of encounters with alien civilizations and technologies.

9 Omens Of Charlemagne’s Death

The Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in A.D. 800. In the last three years of his life, according to his biographer, Einhard, the Emperor was bedeviled by sinister signs and omens. Einhard reports of frequent eclipses of the Sun and Moon, and a black spot on the Sun which lasted seven days. There were also frequent tremblings at the palace at Aix-la-Chapelle, and on Ascension Day, the gallery that connected the palace to the basilica—which Charlemagne built—suddenly collapsed. Another one of Charlemagne’s projects, a wooden bridge over the Rhine at Mainz that took 10 years to build, was accidentally set on fire and was totally consumed in just three hours. During his last Saxon campaign against the Danes, Charlemagne himself saw a ball of fire appear and rush across the sky as he was leaving camp at sunrise. His horse suddenly took a forward plunge, throwing the Emperor violently to the ground. In whatever building he took shelter, strange crackling sounds from the roof were heard. At the basilica at Aix-la-Chapelle, a gilded ball adorning the pinnacle was struck by lightning, causing it to fall and shatter on the bishop’s house next door. All these creepy happenings left Charles unfazed and skeptical. Nevertheless, a few months before his death, people began to notice that the word “Princeps” on the legend inscribed around the basilica’s cornice (identifying “Karolus Princeps” as its builder) had faded and disappeared. Charlemagne finally died on January 28, 814, and was buried in his basilica.

8 Magonia

UFO enthusiasts are likely to interpret the ball of fire seen by Charlemagne in the above story to be an alien spacecraft. Sightings of mysterious objects in the sky are certainly not confined to our age. Around A.D. 820, Archbishop Agobard of Lyon, France, described beings who “fell to Earth” in his book De Grandine et Tonitruis (About Hail and Thunder), a work that seeks to debunk popular superstitions about weather phenomena. He tells us that people in his time believed in a certain region called Magonia, “from which ships come in the clouds” to steal crops. They could apparently strike deals with the “storm-makers,” and the grain and other crops that fell in these storms were gathered by the “aerial sailors” and taken back to Magonia. Agobard was skeptical, calling such beliefs “foolishness” and the people who subscribed to them “crazy.” Nevertheless, a mob of locals claimed to have captured four beings—three men and a woman—who had apparently fallen from one of the ships. They kept the captives in chains for some days. The angry mob was itching for a lynching, and they brought the prisoners to Agobard, who, being more given to reason, pronounced them innocent and let them go. Today, the term Magonia is popular among UFO fans, and a collection of UFO sightings is called, appropriately, The Magonia Database.

7 Changelings

In medieval Britain, it was believed that fairies could steal a child and substitute another—a changeling—in its stead. A particular story is that of a blacksmith whose son, normally a cheerful, healthy lad, lapsed suddenly into lethargy, wasting away so fast that everybody thought he would die. After being in this condition for a long time, an old man approached the smith to tell him that he thought his son might be a changeling. To make sure, the old man proposed a test: Scoop some water into empty eggshells and arrange them around the fire in sight of the boy. The smith followed these instructions in front of the boy, who then sat up from his sickbed and exclaimed, “I am now 800 years old, and I have never seen the like of that before!” This was confirmation that the child was, indeed, a changeling. The old man told the smith that his real son must have been taken by the fairies to a nearby hill they frequented. He then advised the father to get rid of the changeling by lighting a fire and throwing the impostor into it. This the man did, whereupon the changeling let out a yell, leaped through the roof, and disappeared. Armed with only a Bible, the smith then proceeded to invade the fairies’ domain to get his son back. He saw his son among the merry-making fairies and demanded that he be freed. The fairies couldn’t touch him because he was protected by the Bible, so they thrust him and his son out of the hill. Throughout Britain, people often performed similar tests to determine if a suspect baby was a changeling. One test was to put a shoe in a bowl of soup in front of a baby. If it giggled, it meant it understood the joke and it was a fairy. Also, a baby wasn’t human if it found making a loaf of bread in an eggshell amusing. The legend of the changeling allowed medieval people to explain premature deaths in children, as well as childhood diseases, physical and mental deformities, and disabilities.

6 The Royal Touch

For more than 500 years, people have accepted that monarchs, by virtue of their divine right to rule, had the power to heal disease by their touch. One particular malady called scrofula, a tubercular inflammation of the lymph glands in the neck, was believed to be healed when touched by a sovereign. This healing was seen as validation of the monarch’s appointment from God. It was claimed that the first to practice the healing touch was Edward the Confessor, ruler of England from 1042 to 1066. French tradition, on the other hand, has King Philip I initiating it in the 11th century. In medieval times, grand ceremonies were held in which the ruler touched hundreds of people afflicted with scrofula, or the “King’s Evil.” These people then received special gold coins called “touchpieces” that they regarded as amulets. By the 1400s, there was also the custom of healing through touching a coin called an angel, which in turn had been touched by the monarch.

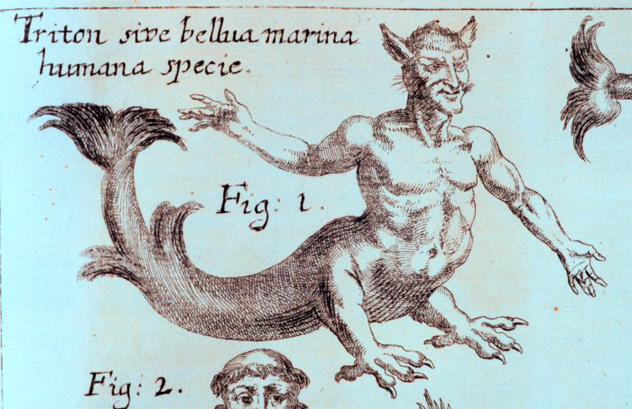

5 The Wild Man Of Orford

Ralph of Coggeshall, abbot of an abbey in Essex, tells us the story of some fishermen from Suffolk who, one day in 1161, caught a naked wild man in their nets near the village of Orford. The “merman,” as they called it, had a long, shaggy beard and a very hairy chest, though his head was almost bald. The creature was hauled off to Orford Castle, where Bartholomew de Glanville was governor. The man was thrown into the dungeon and tortured to make him speak. With no information forthcoming, the locals could not decide if he was a fish or a man, so comfortable and at home was he at sea. They thought that he might be an evil spirit in the body of a drowned sailor. The “merman” displayed no belief in God nor knowledge of Christian rituals. He ate whatever was given him, but he would squeeze the juice out of raw fish first before eating it. After a while, his captors decided to let him out to sea for exercise, but not before fencing him in with nets. Despite their precautions, the merman managed to break through the nets and escape, amazing the onlookers with his agility in the water. The creature did return to his captors, but escaped again after two months, never to be seen again.

4 The Spectral Wild Hunt

Throughout medieval Britain and areas of the Continent, people lived in terror of packs of spectral hounds that swept through the forests in midwinter—the time when the worlds of the living and the dead collide. The hounds would be accompanied by phantom huntsmen and warriors, led by a figure who, in Germanic lands, was identified as Odin, the god of the dead. They were considered portents of death and disaster, and people would fling themselves downward to avoid seeing them. Anyone unfortunate enough to behold the ghostly spectacle might be carried away by it and dropped off miles from where he was taken. At times, the Hunt would break into houses, stealing food and drink. While ordinary folk were terrorized, some who practiced magic would have their souls join in the Hunt while their physical bodies slept. Just hearing the hounds passing overhead amid the darkness and the howl of winter winds was enough to drive someone crazy. Their coming was often accompanied by the sounds of rattling chains and clanging bells. A description of the Hunt is preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1127): ” . . . it was seen and heard by many men: many hunters riding. The hunters were black, and great and loathy, and their hounds all black, and wide-eyed and loathy, and they rode on black horses and black he-goats. This was seen in the very deer park in the town of Peterborough, and in all the woods from the same town to Stamford; and the monks heard the horn blowing that they blew that night. Truthful men who kept watch at night said that it seemed to them that there might be about twenty or thirty horn blowers. This was seen and heard . . . all through Lenten tide until Easter.” In Germany, it was believed that the Hunt included the souls of unbaptized babies, while in France it was said to be led by King Herod pursuing the Holy Innocents.

3 A Place For Evil

Drangey Island, in the North Atlantic, about an hour’s boat ride from northern Iceland, is marked by a sheer cliff face rising 168 meters (551 ft) above sea level. This towering outcrop looming out of the ocean is home to thousands of seabirds. In the Middle Ages, this forbidding, fortress-like island was believed to be home to evil beings and trolls. Men who climbed the cliffs to hunt for birds and their eggs often fell to their deaths, their ropes mysteriously cut. Terrified, people no longer ventured to the cliffs of Drangey, which became a problem for Gudmundur (or Gvendur), the saintly bishop of Holar. The northern Icelandic town had attracted numerous beggars, and feeding them depended on hunting at Drangey. So Gudmundur decided to exorcise the island. With several priests and a barrel of holy water, the bishop began blessing the island, using ropes to negotiate the treacherous cliffs. He was almost finished with his rituals when a gigantic, hairy hand came out of the cliff face and began to cut Gudmundur’s rope. Fortunately, the rope had been blessed beforehand and held. When the creature saw that it couldn’t kill the bishop, it begged, “Stop your blessing, bishop Gvendur, even the evil needs a place to live.” The bishop therefore declared that that part of the cliff should be a place for the evil to dwell, and that people should avoid hunting there. It is said that this spot attracts so many birds since it is the only place on the island where people are off-limits. Bishop Gudmundur began to perform regular blessings of other evil places, but he always took care to leave aside “a place for evil to live.”

2 The Pest Maiden

The Black Death was one of the most devastating plagues to visit humanity. The “Great Mortality” mowed down an entire third of Europe’s population in the 14th century. Part of the terror was that no one really understood what was causing millions to fall dead, and therefore how to avoid being infected. The best explanation put forward by the learned academics of the University of Paris was that the pestilence was caused by a combination of earthquakes and an ill-fated conjunction of the planets. The malignant alignment not only caused the pestilence, but also raised up the storms that spread the noxious fumes from the Earth, which had been released by the quakes. But ordinary, common folk could not comprehend such sophisticated ideas. They would rather believe that the plague was a punishment from God, and was a portent of the end of the world. Plague legends tried to explain how the disease spread—the best known one is the Austrian legend of the Pest Jungfrau, or the Pest Maiden. She was imagined as a being enveloped in a blue flame who flew across the land, spreading the contagion. In Scandinavia, she was believed to emerge from the mouth of a dead victim—also as a blue flame—and fly away to infect the next house. In Lithuania, the Maiden would wave a red scarf through the door or window to let in the plague. One story tells of a heroic man who deliberately waited for the Maiden at his open window with a drawn sword. The Maiden did come, and as soon as she extended her hand to wave her deadly scarf, the man struck and cut off the limb. The brave man died as a result of his deed, but his village was spared, and the scarf was preserved as a relic in the local church. Personifying the plague was surprisingly common in legend. In post-medieval Sweden and Norway, the disease was portrayed as a traveling pair—an old man and an old woman carrying a shovel and a broom, respectively. The old man with the shovel would come and spare some people, but when the old woman went forth with her broom, “not even a mother’s child was left alive.”

1 The Malleus Maleficarum

In the list of history’s most infamous books, the Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) must rank up there with Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Published in 1486, it was written by two German friars, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, to debunk arguments that witchcraft does not exist. It was also meant to serve as a manual for the detection, prosecution, and punishment of witches. It was responsible for the ensuing frenzy of witch hunts which covered Europe with the blood of thousands of victims, mostly women. The Malleus is evidence that some superstitions are far from harmless. The book decrees that witchcraft is heresy, and that not believing in it is also heresy. It asserts that witches are mostly women, and it is female lust that leads women to form pacts with the Devil and copulate with incubi. Midwives are especially singled out for their alleged ability to prevent conception and terminate pregnancies. It accuses them of eating infants and offering live children to the Devil. But the real heinousness of the Malleus and its authors lies in the procedures drawn up to identify and exterminate witches. The accused are to be stripped and searched for the “devil’s marks,” then dunked in water or burned, since people who are under the Devil’s protection cannot be drowned or killed by fire. Using the Malleus as a guide, torture was liberally used to extract confessions or implicate other people throughout the witch hysteria. Gruesome torture devices were developed that could crush or dislocate bones (the Bootikens, strappado), mangle bodily orifices (the Pear), or tear out fingernails (the Turcas). Red-hot pincers were also applied to tear out pieces of flesh. Those found guilty of witchcraft were usually burned at the stake. All in all, there is no more damning testament to the dangers of superstition than the Malleus Maleficarum.