10 Ultimogeniture And Yuan Shao’s Poor Choice

Nobility and royalty often use primogeniture—the exclusive right of inheritance belonging to the eldest son. Ultimogeniture, or appointing the youngest son as heir, is one of the rarest succession laws. Mongols were known to have practiced it, while the Old Testament of the Bible alludes to it occasionally. Yuan Shao, a powerful warlord during China’s Han Dynasty, was facing both territorial conflict and conflict within his family during the first century A.D. On the battlefield, there was Cao Cao, who had a meager force but proved himself as one of the most brilliant minds in ancient China. Then there were his three sons, Yuan Tan, Xi, and Shang. Normally, the eldest would have been designated heir, but Yuan Shao greatly favored the youngest, Shang. As the conflict with Cao Cao wore on, Yuan Shao lost a major battle, and his health deteriorated. He named his youngest son as his heir, causing a great rift between the brothers. With Shao’s passing in the year 202, infighting erupted between the sons. The eldest son Yuan Tan tried to face Cao Cao without his brothers’ aid, resulting in his death. The two remaining brothers fled to the lands of another warlord, who promptly executed them to appease Cao Cao. The affection and priority given to the youngest led the Yuan family to ruin, aided Cao Cao’s rise to power, and brought about the eventual formation of the Three Kingdoms of China.

9From Fratricide To Seniority In The Ottoman Empire

Fratricide, the murder of one’s own sibling, may be a grave crime, but at the height of the Ottoman Empire, it was a common way of saying, “Long live the king . . . death to his brothers!” Ottoman princes commonly squabbled for the right to rule once their father died (or even while he was alive). The prince with the most land and titles assumed command. It couldn’t hurt if he lived near Constantinople as well—he could just run to the palace and declare himself the new ruler. Then, he’d just need to strangle his brothers (and their sons and wives) one by one. Mehmet II introduced this horrible practice in 1451 to eliminate rivals for the throne. In 1617, when Sultan Ahmed died, one of his brothers turned up alive and well. Ritualistic killing of one’s own kin then gave way to Agnatic Seniority (“ekberiyet”), in which the right to rule passes to the eldest living male of the family. The empire dissolved, but the practice of seniority still prevailed, such as in Saudi Arabia. King Abdulaziz Bin Saud, the kingdom’s first ruler, had over 40 sons. The five kings since his death in 1953 have all been brothers, ascending the throne based on seniority (and a bit of politicking). The current ruler, King Abdullah, is nearing the age of 90. Two of his younger brothers have already died, and the new crown prince reportedly suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. Fratricide, meanwhile, is not entirely lost. “Avunculicide,” the killing of one’s uncle, did occur on March 25, 1975, when King Faisal was assassinated by his nephew.

8Royal vs. Bastard

The Inca prince Huascar was born of royal blood, while his half-brother Atahualpa was the son of a concubine. Huascar felt insulted that the bastard Atahualpa would be considered for Sapa Inca (Emperor of the Incas) and demanded unwavering loyalty from him. Atahualpa sent messengers bearing gifts to his half-brother to no avail—Huascar allegedly cut off their noses and sent the men back with their clothes torn. The outrageous act was too much for Atahualpa to bear, and so the brothers went to war in 1529. Three years later, with his troops victorious and Huascar a captive, Atahualpa encountered Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his men, calling them “strange visitors with wool on their faces.” While some of the natives may have thought them gods, Atahualpa thought the visitors stupid—otherwise they wouldn’t be wearing pots on their heads. He even planned to have them swear fealty to him. One lopsided battle later, Atahualpa was a captive. Pizarro, learning of the civil war, allegedly said that he would decide which of the two brothers would rule. Atahualpa, knowing Huascar had a more legitimate claim, ordered his brother drowned. The Spaniards, fearing Atahualpa might incite rebellion, promptly garrotted him as well, despite the huge ransom he offered them. And thus came the beginning of the end for the Incan Empire.

7Two Popes Are Company, Three’s A Schism

In 1309, a Frenchman was elected Pope and decided to live in Avignon under the protection of France. The Avignon Papacy lasted from 1309 to 1377, with several popes (all French) reigning from Avignon instead of Rome. On April 8, 1378, Urban VI was elected as the new Pope—“an Italian who would reside in Rome”—which made the populace rejoice. However, just weeks into his reign, Urban VI proved himself unstable and hostile. A group of cardinals thought it best to supplant him with Clement VII—which, in hindsight, was probably not the best idea. Clement VII took residence not in Rome but in the vacant seat in Avignon. Both popes felt they had a right to the title, power, and riches of the Catholic Church. The major powers of Europe each chose a pope to side with, often based on political alliances, to control the papacy and the region. France naturally defended Clement. So, too, did Scotland, Castille, and Aragon. England, the Holy Roman Empire, and much of Italy sided with Urban. Then in 1409, a council convened in Pisa and elected a third pope—Alexander V. There seemed no end to the division until 1414. Pressured by the Holy Roman Emperor, Alexander’s successor convened a council, which by 1417 had unanimously decided on Martin V as the one true pope. The Popes from Pisa and Avignon (both lines declared as antipopes) were deposed. The previous Roman Pope resigned peacefully—and was the last to do so until Pope Benedict XVI abdicated in 2013.

6A French General’s Unexpected Offer To Be King

In the 19th century, the Swedes overthrew their king and placed the sickly and childless Charles XIII on the throne. The Riksdag (parliament) chose a crown prince, but he suddenly died, leaving it unclear who would rule next. Minor Riksdag member Baron Carl Otto Morner had the answer: French Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. Morner respected Bernadotte’s military and administrative skills, as well as his humane treatment of Swedish prisoners of war in a previous conflict. Alone but convinced of his choice, the baron wrote to Bernadotte and told him of the offer, while spreading pamphlets about the marshal’s deeds among the masses. The Riksdag was furious at Morner’s audacity and ordered him arrested. But the idea had spread, and the public felt that a French general had to be in charge. On August 21, 1810, Bernadotte was named heir presumptive to the Swedish throne. In 1818, when the old king died, the Frenchman rose to become ruler of Sweden and Norway. The “House of Bernadotte” is Sweden’s ruling house even today. Bernadotte’s wife, Desiree Clary, was once engaged to Napoleon before he left her for Josephine—but that was years ago, and now she was an unexpected Queen. And the minor baron who became a kingmaker was appointed Generalissimus of the Swedish army.

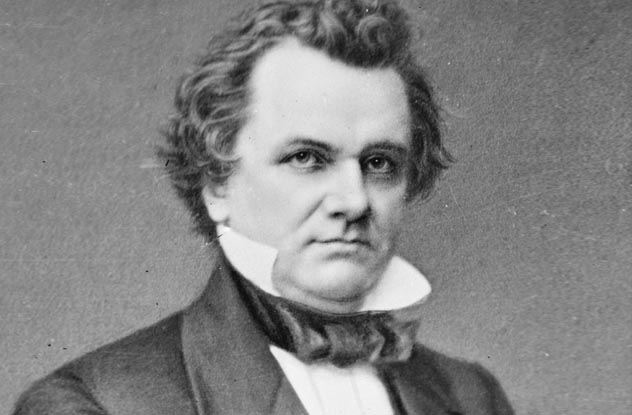

5A Split Party At The Crossroads Of American History

Politics in the United States has often been a hotbed of clashing ideologies, and this was no more evident, nor more profound, than in 1860. Slavery was heavily concentrated in the southern states, but the western coastline of North America was now part of the country. What should the government do if slaveholders claimed lands in those new states? Three major ideologies clashed. The Republican Party sought to prevent the expansion of slavery to the territories, hoping to eradicate slavery through containment. The Democratic Party went by way of popular sovereignty, letting the people decide whether to adopt slavery. Within the Democratic Party, however, a Southern faction wished for the government to uphold the rights of slave owners through and through. During the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, heated arguments ensued between moderates and advocates of slavery, resulting in a deadlock and walkouts of many delegates from the South. The party convened again in Baltimore, resulting in more arguments and more walkouts. By the time it was over, the Democrats fielded Stephen A. Douglas to run for president, but the delegates who left, the Southern Democrats, chose incumbent vice president John C. Breckenridge. The divided party stood against the Republicans and Abraham Lincoln. The Democrats lost the 1860 election, the Republicans won, the South seceded, and America fought the Civil War. But even a united Democratic Party, based on numbers alone, could not have won the election. Lincoln, though losing the popular vote due to receiving almost no support in the South, was guaranteed the lion’s share of the electoral votes as he held the more populous North.

4 Three Men, Two Empty Promises, One Crown

The Bayeux Tapestry, one of the most valuable artifacts in English history, records the interwoven tales of three particular men, all vying for the same prize. The images first tell us of how Harold Godwinson, brother-in-law to English king Edward the Confessor, was shipwrecked off Ponthieu in northern France in 1064. Edward’s first cousin once removed—William, Duke of Normandy—heard of the hapless Harold’s plight and sent for his rescue. Harold then allegedly swore an oath to William to support his claim to the English throne. But promises are made to be broken. Upon Edward the Confessor’s death, the king offered Harold the crown. Harold accepted because according to an ancient Saxon law, bequests made on one’s deathbed are inviolable. William and his contingent were furious. It didn’t help matters that a third claimant, Harald Hardrada of Norway, also eyed the English throne. Decades before, England was ruled by a Danish king who had no heirs—and, apparently, he promised the throne to Hardrada’s father. The Viking Hardrada, aided by Harold Godwinson’s jealous brother Tostig, landed on the shores of England—whereby he asked the English king how much land he was willing to offer to pay him off. Harold replied, “He shall have seven feet of English ground for a grave, or a little more perhaps, as he is so much taller than other men.” On September 25, 1066 at Stamford Bridge, seven feet and more were was given to him. The Vikings and Tostig were slain. But Harold Godwinson had little time to celebrate—William of Normandy had invaded as well. William vanquished Harold at Hastings barely a month later, earning the epithet of “Conqueror.” William of Normandy ended the Saxon reign and became King of England. As many as 25 percent of Britons can claim descent from him to some degree.

3A Karling Tradition That Damned Europe

The Emperor Charlemagne held much of Western Europe as his own domain. His son and heir Louis “The Pious” inherited a vast empire spanning from as far south as the Pyrenees, as far east as the Austrian heartland, and as far north as the lands of the Vikings. The widowed Emperor Louis, who already had three sons from a previous marriage, had to wrestle with the question of who got which kingdom. He planned to divide the empire equally among his three sons; this was the practice of Gavelkind, quite common among the nobility in those days. His eldest, Lothair, would receive Middle Francia (Switzerland, Northern Italy, Burgundy, and the Low Countries), while his second son, Pepin, would receive Aquitaine (Southern France), and his third son, also named Louis, would receive East Francia (Germany) and thus earn the moniker “The German.” Then Louis’s new wife bore him a fourth son, Charles. The Pious One, ever the fair judge, thought it best to redraw the borders to accommodate his newborn. His three elder sons disagreed and rebelled. Emperor Louis greatly favored his youngest son, even disowning Pepin’s children to give him Aquitaine. Louis died in 840, and the Karling feud continued—Charles against Pepin’s sons for Aquitaine; Louis “The German” and Charles against Lothair. Internal strife plagued the hapless dynasty, and the continent split irrevocably. Had Louis and his descendants practiced the aforementioned primogeniture, then the dream of a united Europe could have been achieved as early as the ninth century.

2Alexander’s Last Words

Three simple words at the end of one man’s life changed the world in 323 B.C. When asked on his deathbed to whom he would leave the empire, Alexander the Great replied: “To the strongest.” His Diadochi, or successors, all clamored for a piece of an empire. Ptolemy received Egypt, Lysimachus received Thrace, and Alexander’s adviser Antipater and his lieutenant Craterus had joint rule of Macedonia and Greece. More able leaders claimed their shares—Syria and Phoenicia, Armenia, Babylon, Northern Mesopotamia, Paphlagonia, and parts of India—all divided between generals, admirals, strategists, secretaries, satraps, natives, in-laws, and Alexander’s infant son (who was eventually poisoned). By the time the dust settled almost 50 years later, most of Alexander’s brave men had died in combat, through murderous plots, or from disease. His empire, which had been the largest at the time, dwindled into rump states—either overrun by rebels, conquered by neighboring foreign kingdoms, or taken over by an emerging regional power called Rome. The last kingdom of the Diadochi—Egypt—was annexed by the Romans in 30 B.C. Had Alexander chosen his last words more carefully, would his empire have survived longer? Would his generals have honored his dying wish and accepted a single successor? If that happened, then truly what a world this would have been. Polybius might not have needed to write about the rise of Rome, and cultural openness would have been the norm. Perhaps, somewhere along the way, a Diadochi descendant would stumble further east from India to a more exotic land—where Euclid’s genius would eventually aid Chinese strategist Zhuge Liang, and Zeno’s school of Stoicism would intertwine with the teachings of Confucius.

1A Quiet Housewife Ousts A Two-Decade Dictatorship

In a speech as a recipient of the Fulbright Prize on October 11, 1996, Corazon “Cory” Aquino, former president of the Philippines, regaled the audience with her stories as a simple housewife. She stood by her husband, a former senator, when he alone fought against an arrogant dictatorship and when he challenged the First Lady for a seat in parliament. She never missed a chance to be with him when his jailers permitted it, and for seven and a half years, she waited outside his maximum security prison cell. She held his hand as the life drained out of him in a self-imposed fast of 40 days. She lost him when he returned to the Philippines, against the advice of friends and the warning of his worst enemies. She followed him to his home country—no longer a housewife but a widow when a military escort shot him in the back of the head. Two million people lined the streets to pay homage to him and to voice their outrage when he could no longer be heard. Decades of pent-up anger against the rule of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos finally erupted. A panicked Marcos called for a snap election for the presidency and vice presidency. The opposition saw hope in Cory. But how could a housewife with no political experience challenge a dictator who’d ruled with an iron fist for 20 years? Worse, one of the opposition leaders was a former senator himself who eyed the presidency, and pride would not let him accept that he was a mere running mate. It took the mediation of the Archbishop of Manila to unite the various factions—with Cory at the helm. Cory lost, but investigations uncovered massive vote-buying, electoral fraud, and sabotage. The tumult reached a boiling point on February 22, 1986 when disgruntled military leaders sought to rebel. The Archbishop of Manila urged the Filipino populace to rally in EDSA (a major thoroughfare in the capital) in support of the rebels to bring them food and supplies. Nuns and devotees held rosaries and knelt in prayer in front of tanks; millions of people packed the highways singing a melodic anthem. Gunships were ordered to attack rebel positions, and the president’s broadcast was abruptly cut off. Three days later, the peaceful EDSA revolution saw Marcos whisked away to exile in the United States. Cory Aquino, the quiet housewife of a slain martyr, was proclaimed as the first female president of the Philippines. She died of cancer on August 1, 2009, just a few weeks shy of the 26th anniversary of her husband’s death. History had an odd way of repeating itself—the wave of support that characterized Ninoy’s death was also present at Cory’s passing. Their only son suddenly found himself in the limelight. He won the national election in 2010. Jo is actually an EDSA baby himself—a child born around the time of the EDSA Revolution, when a housewife toppled a dictatorship. Share your thoughts in the comments section or email him at [email protected].