10Norwegian Butter Crisis

The Norwegian Butter Crisis of 2011 was an unfortunate combination of reduced supply and increased demand. Heavy summer rain was followed by a 20-percent rise in demand in October and 30 percent the following month. By mid-December, with Christmas approaching, the price of a pack of butter jumped to 300 Krone, or $50. Those who had butter took advantage. People began auctioning butter online, with a going rate of $100 for 450 grams (1 lb). Over the border, Swedish supermarkets saw butter sales jump 2,000 percent, nearly all of it going to visiting Norwegians. A couple Swedes were caught trying to smuggle 250 kilograms (550 lb) into the country. In the aftermath, retailers demanded compensation for $7 million in losses.

9Toilet Paper Panics Of 1973

In December 1973, Johnny Carson spooked Americans by mentioning an impending shortage of toilet paper. Gullible consumers rushed to stock up, and several stores took advantage by ramping up their prices. Luckily, that crisis was pretty much over the next night when Carson went on air to explain the entire thing was a joke. Yet this wasn’t the only toilet paper shortage in 1973. Across the Pacific, Japan was getting jittery about the Arab-Israeli War. The Japanese relied heavily on oil from the Middle East, and one of their government ministers went on television on October 31 to ask people to use paper sparingly. It’s the worst thing he could have done. A few hundred people queued up outside an Osaka supermarket the next day and cleared out all of the toilet paper. When that made the news, others followed suit. Another official begged for calm on November 2, saying there was plenty of toilet paper for everyone in the country. This just fanned the flames, and the entire country began hoarding as much toilet paper as they could. By the time the crisis came to an end, most people had stocked up on at least a year’s worth of the stuff. Despite that, the human memory is so odd that those who remember the time recall it as a period of shortage, with barely a roll in sight.

8American Meat Shortage

The American meat shortage of 1910 followed a loss in native animal species, combined with a booming human population. While a lack of meat in the US is an unusual enough prospect, one particular plan to solve the crisis stood out. Two men had a dream to meet the nation’s appetite by creating a hippopotamus farm in Louisiana. Louisiana was facing its own strange problem. The Japanese water hyacinth, brought into the state during a cotton exhibition, had gotten out and started clogging up waterways. Congressman Robert Broussard caught wind of the hippo idea from explorer Frederick Burnham, who said the hippos would devour the hyacinths quite gladly. He passed a bill to acquire $250,000 to make it happen. The Department of Agriculture thought beef was a better solution. They increased the land available for raising conventional cattle, including many of the swamps that would’ve housed the much-larger African animals. But the idea of eating hippos was still popular in the 1960s, when Popular Science said the “particularly delicious and not at all fatty” meat could help meet food shortages in North Africa.

7Myanmar Is Paranoid About Cash

Myanmar is a country desperate for economic growth. It is also a country where almost no one is willing to trust a bank and where even fewer people are willing to trust an ATM. In fact, the first ATM in the country didn’t arrive until 2013. For a long time, international sanctions against Myanmar’s military dictatorship blocked Visa and MasterCard from setting up facilities. Banks were horribly corrupt, and people often had to bribe staff to withdraw their own money. The result is that less than 10 percent of the population has a bank account. People just carry their cash with them. But the issue runs deeper: People won’t accept cash in anything less than pristine condition. Any crease, tear, or ink mark, and people may refuse to take a note. People press their money in books to flatten the bills. As the country transitions to democracy, it’s trying everything it can to get people using the banking system. While there are some signs of progress, there’s a very long way to go.

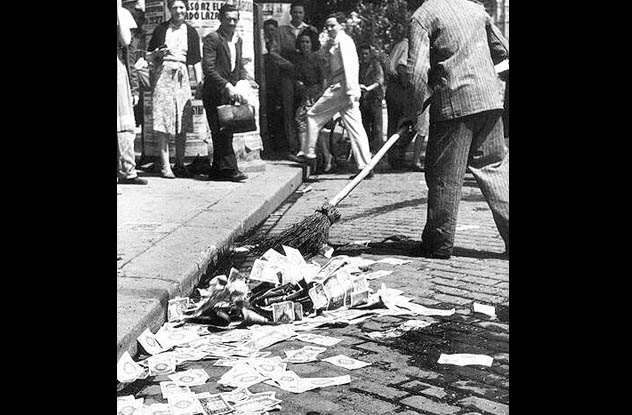

6Hungarian Hyperinflation

Inflation is probably among the most normal of national problems. Hyperinflation is rarer but still fairly frequent. Inflation in 1920s Germany peaked at 32,400 percent per month. Yet the hyperinflation that happened in Hungary in 1945 and 1946 stands out in sheer scale. It was one trillion times greater than Weimar Germany’s inflation. The situation began in 1945, but by the inflation’s height in 1946, prices were doubling every 15.6 hours. In January 1946, the government replaced the pengo with another currency, the adopengo, worth several trillion times the original. Pengo stayed in circulation, its value still dropping, until it was literally impossible to get anything for a 100-million-pengo bill. The highest denomination bill printed was worth 100 quadrillion pengo. Loose, worthless bills piled up in the streets. By the time the problem came to an end, every single note in circulation in the entire country combined was worth less than one American cent. The Hungarian government introduced the forint on August 1, 1946. It was worth the equivalent of 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengo. The new currency was backed by gold and foreign money, leaving it stable enough to survive until today.

5Switzerland’s Economy Is Too Good

Since the 2008 financial crisis, pretty much every country has had to wrestle with demons in their economy. One country that weathered the financial collapse extremely well was Switzerland. When the Eurozone began collapsing around them, the Swiss economy maintained low debt, low unemployment, and healthy exports. Having the most resilient economy on the continent may not sound like a problem. Yet Switzerland is still part of the larger world, and the world made the country a victim of its own success. Currency traders looking for a safe investment shifted to Swiss francs, increasing the value of the currency by 30 percent compared to the Euro. An overvalued franc made Swiss exports more expensive, hurting Swiss companies. Negative inflation has other bad consequences as well, such as greatly increasing the real cost of citizens’ fixed debt. The government had to artificially weaken the value of their own currency, a situation they would’ve avoided had they just managed their affairs as poorly as the rest of Europe.

4Penis Panic

Koro is a mass delusion in which people believe their genitals are shrinking or have been stolen entirely. It has overtaken entire towns and villages in several African countries, where whole groups of men claim their penises are shrinking. They’ll often attach string or metal clamps to their genitals to stretch them safely outside the body until a shaman can be found. The thefts are often blamed on sorcerers. In 2008 in Congo, rumors began that people wearing gold rings in communal taxis were performing penis theft spells on their fellow passengers. It became the talk of local radio stations. Yet the penis panic itself wasn’t the problem—it was the public reaction. The Congo police were forced to arrest 13 suspected penis sorcerers and 14 alleged victims after the victims attacked the sorcerers as a mob. It was likely a sensible precaution. An episode in Ghana in the 1990s saw 12 penis snatchers beaten to death by crowds. In Nigeria, 12 people were killed in 2001, and five were killed in Benin the same year. The Congo police chief explained his frustration, saying, “When you try to tell the victims that their penises are still there, they tell you that it’s become tiny or that they’ve become impotent. To that, I tell them, ‘How do you know if you haven’t gone home and tried it?’ ”

3Korea’s Kimchi Crisis

South Korea has no food more important than kimchi. The fermented cabbage dish almost has a religious status in the country. It’s served with every meal. Restaurants offer it for free, like ketchup in the US. So it was a big problem when the key ingredient, Napa cabbage, rose in price by nearly 500 percent in the space of a month in 2010. The result was a massive spike in the price of kimchi, and with it came a shortage. Newspapers dubbed it “a national tragedy” and “a once-in-a-century crisis.” The shortage followed heavy rain, on top of a relatively small harvest after a bumper year previously. In response, people began rustling cabbages. In one province, a group of men were arrested when they tried to make off with 400 of them. Koreans began calling the sauce “keum-chi,” as keum means gold. The government suspended import tariffs on cabbage and radishes. In a display of solidarity, the president declared he would eat only inferior cabbage, the sort from Europe and the US. Meanwhile, local governments began offering subsidized cabbage, causing people to queue for half an hour to pick up a bag.

2Operation Pig Bristle

A housing shortage is a very common national problem. The UK has one, which doesn’t look to be resolved any time soon. The same goes for Australia, which has matched the UK in failing to build enough affordable housing for a few decades. Yet it’s not the first time the Aussies have needed new places to hide from the country’s various dangers. In 1944, the Australian government introduced a scheme to build new houses to meet their increasing demand. Yet they ran into a bizarre problem a couple of years into the project—a chronic shortage of paintbrushes. Worse than that, there was a chronic shortage of the pig bristles needed to make more, and the only viable source was China. At the time, China was in the middle of a civil war, and getting imports was pretty difficult. The Royal Australian Air Force received the task of acquiring 20 tons of pig bristles from Chongqing. The mission was launched in May with the fitting title of “Operation Pig Bristle,” and it took five months to complete the work.

1Lab Mice Shortage

On May 10, 1989, a fire tore through the Jackson Laboratory in Maine. It destroyed mouse production facilities and killed 400,000 laboratory mice. Among them were unique or unusual strains used for research in several thousand diseases including AIDS and types of cancer. The facility supplied 6,500 research labs across the US and the wider world for research worth $1 billion. The fire was deemed “a national disaster” by officials from the laboratory. Many experiments already in progress had to be abandoned, as changing to a different supplier would skew results. The Mayo Clinic, among the institutes affected, had to postpone tests on an arthritis drug. The impact hit medical researchers across the globe, as the laboratory had been selling 40,000 mice every week to 11,200 labs. The loss to the Jackson Laboratory was around $40 million. Their insurance covered only $15 million in damages. Despite receiving unsolicited donations, including $750,000 from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the laboratory asked Congress for $25 million to rebuild and get the country’s medical research back up to speed.