An entirely new discipline of archaeology called ice patch archaeology is evolving. Ice patches are long frozen areas of water and snow that lie on the always shaded sides of mountain ranges. Each year, layer upon layer of snow and ice would build up, sometimes covering and freezing ancient artifacts, or in this case, ancient excrement. Ice patches are invisible in the winter as the are covered by yearly snow pack. In the summer months however, they emerge as small ice oases that persist until the next winter. In 1997 hunters in the Yukon Territories of Canada discovered layers of ancient caribou dung that were frozen between alternating years of accumulated ice and snow, kind of like a caribou dung Oreo cookie. The dung is an important discovery for scientists who can examine this organic material for records of what the animals ate and what kind of environment they lived in, thousands of years ago. Pollen spores, plants, insects and parasites reveal much about the environment of the time. The DNA of the animals can determine hereditary information about the species and even migratory patterns. Perhaps most amazing of all was what was found in the dung—a 4,000 year old dart shaft. It appears ancient caribou hunters knew well the animals habits. In the hot summer months the caribou would seek shelter in the shaded sides of mountains and lay down on the always frozen ice patches. The hunters took full advantage of this and hunted the animals when they were congregated in an icy area.

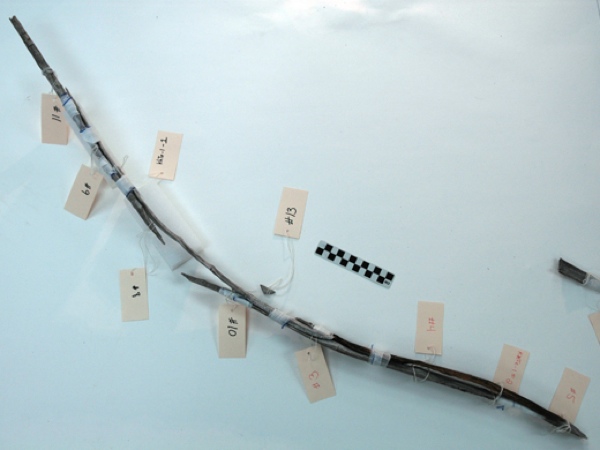

Ten thousand years ago a hunter in northern Canada took aim at an animal, possibly a caribou, with a state of the art hunting weapon—the atlatl dart. He or she may have missed, or possibly dropped and lost their weapon, which was found centuries later in a melting ice patch giving scientists a rare glimpse into an ancient hunting tool in North America. Dating back almost 30,000 years in Europe, the atlatl dart was used by Native Americans as far back as 10,000 years ago. The atlatl dart is probably the first true weapon system consisting of both a projectile and a launching mechanism. It consists of a wooden handle that can be gripped at one end and has a notch or spur in the other end. In the spur the hunter would place a 4–6 foot long (121–182 cm) dart. The atlatl dart allowed hunters to throw the dart further, with more power, and accuracy, than a spear. In North America, the atlatl dart predates the bow and arrow by about 8,000 years. The dart that was discovered was made of willow, had markings on it that indicated ownership (this is my dart) by the maker, as well as feathers from birds of prey. The discovery of the 10,000 year old atlatl dart is an example of the kind of ancient artifact that would be destroyed had it been lost in a glacier, but survived in a more static frozen environment like an ice patch.

One of the early scientists to champion ice patch archaeology, Tom Andrews, realized the importance of the melting ice patches and the frozen treasures that would be lost unless someone went to look for them. Unfortunately, ice patches are located in the rugged and inaccessible mountains ranges of Alaska and the Canadian arctic. In 2000 Andrews finally raised the money to buy aerial photographs of the Mackenzie Mountains of the Yukon Territory of Canada. He located several promising ice patches and five years later set off in helicopters to explore. What they found not only showed the importance of ice patch archaeology, it gave him the ability to raise more funds to do more archaeology. That year, they found several fragments of wood in one melting ice patch that turned out to be an entire, 340 year old willow hunting bow. “The implements are truly amazing. There are wooden arrows and dart shafts so fine you can’t believe someone sat down with a stone and made them,” Andrews said.

Artifacts emerging form the melting ice show how Native American hunters used advanced technology to their benefit. One example was an ancient barbed antler projectile with barbed edges along the arrow shaft. It looked much like an ancient whaling harpoon. Once the arrow penetrated the animal, it would have been very hard to remove as the barbs ran backwards from the point of the arrow, much like a barb on a fishing hook. But that was not the only cutting edge hunting technology employed by these hunters. The same arrow was tipped with a copper arrowhead fashioned from a lump of copper. This was an exceedingly complex and efficient killing tool, meticulously hand crafted by the hunter, thousands of years ago. All of it preserved in the ice to be discovered as the ice patch melted.

Not every artifact that archaeologists have found in the ice patches is a hunting instrument. One of the more intriguing finds were cut sections of wood from a willow tree that were not meant to be part of arrows, bows, darts, etc. The 1,500-2,000 year old willow wood shows clear signs of being cut by humans, but if not for hunting, then for what purpose? As the ice patch from which they were discovered was more than a kilometer above the nearest willow tree and well above the tree line, scientists believe the cut wood was probably cut below the ice patch and carried there. Scientists originally thought the wood was cut, transported to the ice patch, and used as cover or camouflage for the hunters. However, such cover is not really needed for hunters to sneak up on and kill the caribou when they are concentrated in such a small area as an ice patch. Scientists now believe what they have found are early remnants of ancient lean too shelters, set up above the ice patch, where the hunters lodged, and waited for the hunt.

Another discovery of a well-preserved non-hunting ancient artifact was made in 2003. While walking along the edge of a melting ice patch, an archeologist caught a glimpse of something unusual. It turned out to be a 650-year-old birch bark basket. The basket was about 2.3 inches (6 cm) high with slopping edges, and about 9.8 inches (25 cm) wide. It was hand stitched and the stitch holes were still visible. It was made of folded birch bark with reinforced birch wood panels for sidewalls. Though no evidence of plant matter was found, the basket was probably used for gathering berries which would be in bloom at the time of the year the hunters were hunting the caribou at the ice patches (late May-through July).

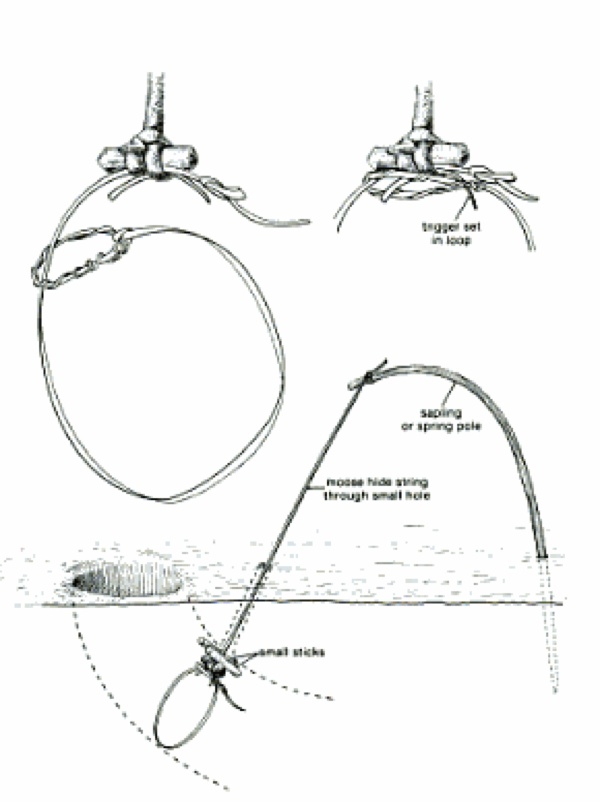

In 2004 archaeologists discovered in an ice patch a 30 inch (75 cm) long spruce stave which had a hook on one end and a point on the other. They immediately recognized it as a gopher stick used by Native Americans of the region to set ground squirrel and gopher snares. It is an ingenious device used to place pre-made snares several inches below the ground at the entrance hole for a den. The hocked end of the gopher stick is pushed down through the soil at the top of the burrow. The stick holds the snare and places it inside the burrow, just at the entrance. Once the snare is set, the person removes the pole with the one end of the snare line (made of sinew) still hocked to the hooked end of the stick. The sinew snare line is pulled out, leaving the loop or noose inside the den. The hunter than attaches the other end of the snare line to a bent sapling branch anchored in the ground several inches away. As the rodent exits the burrow its head becomes caught in the snare and the spring-loaded action of the bent sapling pulls it tight around the animals neck, trapping it. The gopher stick was 1,800 years old.

Artifacts are being discovered as bodies of ice melt and retreat around the world. In Juvfonna, Norway, scientists have discovered hunting gear made from reindeer that they believe was used by Vikings. The artifacts are being found littering the edge of the melting Juvfonna ice field. Scientists have described the melting glacier, disgorging hundreds of artifacts, as a time machine. In Norse mythology the Jotunheimen Mountains were the home of ice giants. Now scientists are finding what the ice giants of lore used in their daily lives. Specialized hunting sticks used to drive reindeer, bows and arrows, and leather shoe remnants have all been found in the area. They date back as far as 3,400 years. Amazingly, by using GPS positioning of the recovered items, the scientists have calculated the Vikings drove the reindeer, using the specialized sticks (which had a piece of wood attached to the end of the stick by string, so the wood flapped about) standing about 6.5 feet (2 meters) apart from each other. The noise of the drivers and their flapping wooden sticks pushed the reindeer towards the hunters.

Most people have heard of Otzi, the Ice Man found in a melting glacier in the Italian Alps. Otzi is one of the oldest and best-preserved human bodies ever discovered. He was found with many of his hunting implements and clothing. But not as many people have heard of Schnidejochzi. This is because, well, I made him up. Actually, this may be the name given to this hunter, if his body is ever found. If the missing body of this hunter ever emerges from the ice, the way Otzi did, he may become just as famous because he is 1,000 years older than Otzi. Scientists recently discovered over 300 artifacts emerging from the melting glaciers in the mountain pass of Schnidejoch in the Swiss Alps. Some of these artifacts appear to have belonged to a hunter similar to Otzi including a bow, arrow shafts, arrows, a 5.2 foot (1.6 meter) long birch bark container for the hunting implements, as well as a pair of leather leggings and shoes. The leather leggings and shoes are some of the oldest ever found in Europe. DNA testing has shown the leggings were made of goatskin from a species of goat not previously thought to be found in Europe. Scientists are still looking and hope someday to find the hunter who would date to 4,500 B.C.–1,000 years older than Otzi. Possible picture to use:

Sometime around the year 1700, a man (estimated to be seventeen to twenty-two years old) was hunting in what is today British Columbia, Canada. Somehow, he fell into a glacier, and there he remained frozen until in 1999 when three hikers found several intriguing instruments along the face of a melting and retreating glacier. They saw a walking stick, a fur, and a bone and thought it might be an important discovery. Bringing scientists back to the spot, they then found the torso, left arm and hand, and further away, parts of the lower portion of the body. The man they had discovered would be named Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi which in the Southern Tutchone language means long ago person. Long Ago Person was well dressed while out hunting. He wore a robe made with ninety-five animal skins, mostly gopher and squirrel stitched together with sinew. Inside the folds of his robe scientists found the scales of fish, perhaps he had carried a fish sandwich for lunch? He also carried a walking stick and an iron-blade knife as well as a spear thrower and wooden dart. Still more finds turned up including a leather pouch, a woven hat, and what turned out to be the man’s own personal medicine bag. So important was a Native American’s personal medicine bag that it was never opened by the scientists and Native Americans who helped with the discovery. His DNA was matched against blood samples drawn from 300 members of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. Of those, seventeen showed a close maternal match to Long Ago Man, showing they were decedents or relations. Of those, fifteen of the seventeen belonged to the Wolf Clan indicating that Long Ago Person may have been a member of this clan. In 2001 Long Ago Person was cremated and his ashes returned to the glacier. Patrick Weidinger—who used to write lists under his nom de plume VanOwensBody, is a frequent Listverse contributor. He lives in Southeast Pennsylvania, USA.