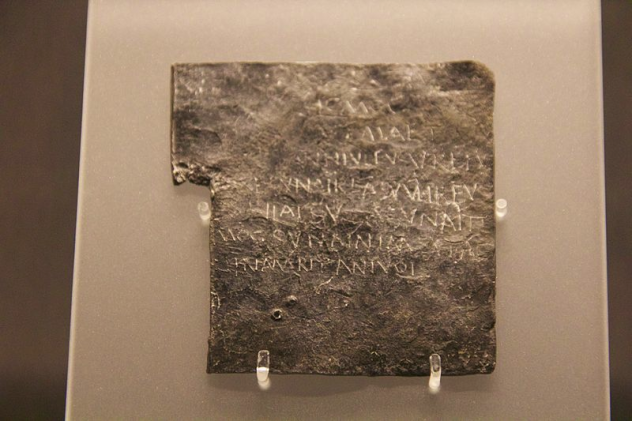

10 The Larzac Curse Tablets

A set of lead tablets were discovered in 1983 in a tomb in Larzac, France. Written in Gaulish with Latin letters, the tablets are more than a curse; they’re also the longest known Gaulish text and a pretty fascinating look at what kind of drama was going on in Gaulish France sometime around AD 100. The curse comes in two parts on two tablets, written by two different people. One tablet has been translated as a sort of documentation of a conflict between several witches, while the second tablet is a curse that tries to undo—or at least lessen—the evil magic that came from the conflict. Scholars are still debating over what the text says, but it’s generally accepted that the curse was written by someone who thought that they had been the victim of the evil deeds of a group of witches. The second tablet, placed in the tomb believed to have belonged to the guilty party, was an appeal to a goddess named Adsagona. She’s asked to turn the evil deeds of the witches back on them in death, essentially a request for some karmic justice. Some of the parties involved are named, as well. Severa Tertionicna is called a “writer” as well as a bunch of other things throughout the text—sorceress, binding woman, soothsayer. The targets of her curses are called the “bewitched” and are referred to as mother and daughter, but no one’s been able to decide how literal that is. They have, however, decoded a little bit about the rituals that supposedly took place. Severa is connected with the epithet licia-, which thanks to a cross-reference to a passage by Ovid, seems to have something to do with binding magic and the weaving of threads both literal and figurative. It pops up in relation to weaving magic in Virgil, too, in which three threads of three different colors symbolize a person’s destiny. It seems likely that whatever Severa supposedly did to her victims was some seriously dark stuff, and outliving the witch to turn it around on her suggests that they wanted nothing short of some eternal torment for her.

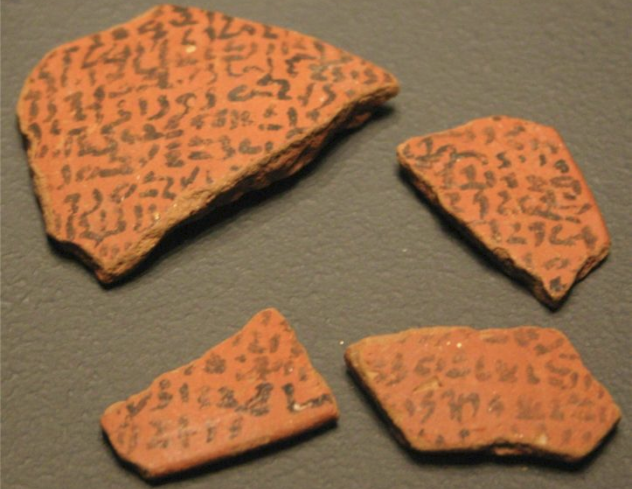

9 The Execration Texts

More than 1,000 examples of execration texts and rituals have been found in Egypt, most dating to the period of the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 BC). The earliest texts, found in Giza and dating to the rule of Pepi II (2250 BC), condemn anyone who would rebel against the rule of the divine king, naming “all people, all patricians, all commoners [ . . . ] who will rebel or who will plot by saying plots or by speaking anything evil against Upper Egypt or Lower Egypt forever.” There’s a lot of variation in specific content across the huge number of texts that have been found, but the basics are the same. Images or texts specifying the target of the curse are inscribed on the surface of pots or figurines that are then broken in the hopes of visiting the same fate on the names that had been written on their surface. In some cases, military opponents might be inscribed next to an image of a bound person, sometimes labeled with names, sometimes with designations, such as the “chief” of a tribe or family. Threats can be rather all-encompassing, like the one that pointed the finger at Pepi II’s naysayers, while others name specific individuals. The idea of the clay figurine as an enemy isn’t just one of convenience; it hearkens back to the creation myth of Khnum, who created the human race by building them on a potter’s wheel. The lump of clay was thought to be helpless in the hands of its creator, who had complete power over the final form of the figure and its fate. The so-called “rebellion formula” was found throughout centuries of execration texts. By the era of the Middle Kingdom, the texts were massive documents naming everyone from rulers and chieftains to messengers and servants. The broken pieces of the tablets, sometimes copied over and over by different scribes, have been found in tombs, interred in jugs, and sealed in more than one necropolis. Just where the magical power comes from, though, is still up for debate. Some scholars think that it wasn’t the writing of the names and the breaking of the clay that was thought to conjure the magic, but rather the rituals that the pieces were subjected to before they were entombed.

8 The Cursed Greengrocer

There are plenty of people you might think are worth the trouble of cursing. Military opponents, love rivals, that one sibling in every family that no one talks about . . . it’s a long list, but we’re pretty sure that the man who sells your fruits and vegetables probably isn’t anywhere on it. Around 1,700 years ago, however, there was a greengrocer living in Antioch who didn’t just get on someone’s bad side; he did something that made him the target of a rather long, Old Testament–style, fire and brimstone curse. Discovered in a former Roman city in southeastern Turkey, the tablet was translated by University of Washington scholars in an attempt to decode not just the curse itself, but why this seemingly unlikely curse was issued in the first place. The double-sided lead tablet starts out strong, calling for thunder and lightning to strike down the greengrocer, named Babylas. It’s a plea for all the power of Yahweh to be directed toward the apparently offensive man, for all the rage of a divine being who killed Egypt’s firstborns to turn toward Babylas. So what did the greengrocer do to earn himself such divine wrath? The name of the person behind the curse isn’t mentioned, but it’s likely that there was some kind of business rivalry going on that led to the man turning to curses to get rid of the competition. The name of the greengrocer, Babylas, might hold a clue, too. At the time, the Roman city was in the grip of a religious revolution, and at the same time the greengrocer was cursed, another man named Babylas was martyred for his Christian beliefs. The Bishop of Antioch was killed in the third century, making it possible that the greengrocer was targeted not for his business sense, but for his religion.

7 Cursing Venusta

While Babylas the greengrocer might have had one of the most unlikely professions for being the target of a curse, the curses leveled at a slave named Venusta are notable for their sheer quantity. In the early 1960s, an excavation of Morgantina in Sicily uncovered a group of 10 lead tablets that dated back to sometime in the second or first century BC. The tablets were nearly illegible, but more recent restoration efforts have allowed researchers to get an idea of what they mean. Four of them are curses that name a slave called Venusta. As it’s a fairly common name, there’s been some debate as to whether the curses were meant for different people or the same one, but it’s thought that her owner, who’s also named in a couple of the tablets, can be identified as the same person based on the spacing of missing letters and those that are still barely legible. We don’t know why Venusta was so disliked, but we do know that she must have done something pretty bad to be cursed like she was. The rest of the curse remains intact on the tablets, and it’s an appeal to the gods to take her to Hell. The messenger god Hermes is named, presumably to get his attention as an escort, along with Gaia and all the gods of the underworld; the writers are asking that she be taken off to the underworld with them. Once they were written, the tablets were probably subjected to some kind of ritual involving hair, herbs, or fire before being thrown into a pit or pool at the sanctuary of Morgantina. Watery pits were often seen as entrances to the underworld, and it was clearly hoped that the gods would get the message.

6 The Uley Curse Tablets

In the late 1970s, excavations on West Hill near Uley in Gloucestershire uncovered a treasure trove of artifacts from a ceremonial site that had existed from the end of the Iron Age through the Middle Ages. Buried there were a series of almost 100 rolled lead curse tablets, and they’re a priceless look into what was important in third-century life. One is a seven-line appeal to Mercury, asking that he “exact vengeance for the gloves which have been lost; that he take blood and health from the person who has stolen them.” Revenge against a thief is a common theme throughout the texts that have been translated, but this one’s notable for another reason: It’s the earliest and one of the only references to gloves in Roman Britain. Another condemns a thief to a pretty horrible existence until he returns some stolen merchandise to the temple of Mercury. Until that time, it was hoped that Mercury would intervene and make the thief unable to “urinate nor defecate nor speak nor sleep nor stay awake nor [have] well being or health.” While a lot of the thieves are as unknown as the petitioners, there are some examples of names being included in the curse tablets’ text. In one, a petitioner named Canacus claims that a man named Vitalinus and his son, Natalinus, have stolen one of his animals. He wants Mercury to take away their health until he gets his animal back. Another text shows how long we’ve been calling each other names—and proudly boasting of our own handles. That one, written over a stolen cloak, bears the name of the petitioner, Mintla Rufus. He’s hoping for “divine retribution” for the man or woman who stole the material that was going to be used for a cloak. While “Rufus” is a perfectly respectable name for a citizen of Roman Britain (and means “red”), “Mintla” is a little more unconventional word to see used as a name. It means “phallus.”

5 Pella Curse Tablet

The Pella curse tablet dates to sometime in the first half of the fourth century BC. As far as language scholars are concerned, its chief importance comes from the idea that it seems to confirm that both the Ancient Macedonian language and Greek were spoken in the city that would hold onto its fame as Alexander the Great’s capital. It’s thought to be one of the earliest surviving Macedonian texts, and it tells one side of a tragic love story. The writer of the curse clearly has a thing for Dionysophon, directing her curse toward “all other women, and widows and virgins, but especially Thetima.” It seems as though the wedding of Thetima and Dionysophon was imminent, and she’s going to extreme measures to see that it doesn’t happen. The curse continues, wishing Thetima into the care of Makron (the person with whom the scroll was buried) and all the demons that he’s presumably going to meet on his trip to the underworld. Any other woman who marries Dionysophon is going to be heading there as well, and only when the writer digs up the scrolls and reads them again will her beloved be permitted to marry—and only to her. The writer was clearly covering all her bases, as it says that if Thetima does marry Dionysophon, then “evil Thetima will perish evilly,” while good fortune finds the writer. We can presume that this one didn’t work, as it was uncovered in Pella in 1986. At around the same time the curse tablet was written, there were some major things happening in the city. It became the capital of the entire kingdom of Macedon, there was a major overhaul of the government and the military, and it was at the center of Macedonian art, science, and literature. In the middle of it all remained the problems of love and of the heart. The table is a fascinating look into everyday life, and it not only speaks volumes about language, but it’s a testament to the rather comforting thought that no matter what’s going on in the world, our personal problems are timeless.

4 The City Of David’s Curse Tablet

Jerusalem’s City of David has been occupied for a staggering 6,000 years. That’s a lot of history to excavate, and when the Israel Antiquities Authority was working at the site of a Roman mansion built in the late third century, they found a 1,700-year-old curse. The petitioner, a woman named Kyrilla, likely hired a magician to write the Greek text on the tablet, and she certainly wasn’t taking any chances. The curse appeals to gods of three different religions—the Babylonian Ereschigal, the Gnostic Abrasax, and the Greek Hecate, Persephone, Pluto, and Hermes. There are also some references to early Christian concepts, just in case they were listening, too. Her target was a man named Iennys, who scholars think was a member of the middle or upper class and the other half of a legal dispute that Kyrilla was involved in. It’s not clear what the dispute was over, but we’re betting it was something pretty juicy. Kyrilla’s magician wrote, “I strike and strike down and nail down the tongue, the eyes, the wrath, the ire, the anger, the procrastination, the opposition of Iennys,” and it’s likely that rituals involving hammering and nailing went along with the creation of the text. The idea of nails as a way to gain power over the target shows up in cultures around the world. The mansion in which the tablet was found was also filled with artifacts that spoke of the wealth of its occupants, from carved gemstones to intricate statues and figurines. It’s thought that the tablet was hidden in the second-floor room because it was likely where Iennys worked, putting him in close, unknowing contact with the curse. Strangely, historians have been able to pinpoint the date of the mansion’s destruction with unusual accuracy—May 18 or 19, 363. Those were the dates of several earthquakes that decimated the area, along with the offices and the building that Kyrilla plotted to hide her curse in.

3 The Bath Curse Tablets

Bath is famous for the hot springs that give the town its name, and it’s thought that there has been human activity at the site dating back more than 10,000 years. The city wasn’t founded until around 863 BC, when the waters supposedly cured Prince Bladud of his leprosy. Throughout the Roman occupation of England, the springs at Bath were a sacred place, and it was during the excavations from 1978 to 1983 that we learned most of what we know about the site. Sulis was the Celtic version of the Roman goddess of wisdom, and during the Roman era, the springs at Bath were an access point to the goddess. Lead tablets with prayers and pleas were thrown into the spring in the hopes that Sulis would hear and answer their pleas. Sometimes, those pleas were curses. It wasn’t until the baths were excavated in 1878–79 that offerings to Sulis were removed from the sludge. Along things like coins and gems, a pair of lead tablets were found. They remained untranslated—and the subject of rather fanciful theories—for some time. Finally, one of the tablets was translated as, “May the person who has stolen Vilbia from me become as liquid as water.” The curse was followed by 10 names, as the writer was giving the goddess a heads-up as to who the culprit might be. The names were of both males and females, and at first, it was thought to be a curse on a love rival. That, of course, makes no sense whatsoever, as anyone who had been paying even a little bit of attention would know who had stolen the writer’s girlfriend. It’s now thought that “Vilbia” is a mistake, and it was simply a reference to a stolen object. Roman Britain is the only place where curse tablets have ever been found because of theft, and for a long time, the Bath curse tablet was something of an oddity. In 1978, the springs were the site of a modern tragedy, a death from amoebic meningitis. That led to a complete excavation and cleanup of the site, which included tearing out the bath’s Victorian-era floor. Below that, archaeologists found the remains of a Roman roof with more than 12,000 coins, pieces of jewelry, and more than 100 curse tablets. The process of unrolling and cleaning the tablets was a painstaking one, and it ended up revealing a whole host of ancient offenses. Many might seem trivial today, but there’s no mistaking how important they once were. Take Docilianus, for example, who wrote the curse that read, “I curse him who has stolen my hooded cloak [ . . . ] that the goddess Sulis may afflict him with maximum death.”

2 Hekate’s Curses

In 2009, the Museo Archeologico Civico di Bologna found two Roman curse tablets that had been laying around, untranslated, since sometime in the 19th century. They’ve been dated to the end of the Roman era and are approximately 1,600 years old, but the museum had no idea where they were originally found. The translation, though, shows that there are at least a couple people who will live on in infamy. One is the only example of a curse directed at a Roman senator. His name was Fistus, and he served in the Senate at a time when its power had taken a definite downturn. He still would have been wealthy, but at this point in history, at least one person was no longer afraid of the consequences of the possible discovery of someone appealing to the gods to dissolve his limbs and crush him, a verb that shows up in the curse four times. The other tablet is a curse directed at a veterinarian with the unlikely name of Porcello, which means “pig.” It’s unclear whether it was a personal conflict or perhaps a professional one that led to Porcello being targeted by a curse tablet. Not only was it an appeal for him and his wife, Maurilla, to be destroyed, crushed, strangled, and killed, but there’s also an etching of a little mummified Porcello included on the tablet. Similar to the idea of rituals involving nails and spikes, the imagery was likely believed to give the curse even more power over its target. Both curses have another image inscribed on them—that of a woman with snakes for hair. It’s likely the image of Hekate, goddess of necromancy, the night, witchcraft, and magic, who kept two transformed women as her dog and polecat familiars.

1 The ‘Ancient’ Curse Of The Egyptian Mummy

As ancient curses go, it’s one of the most famous. After the 1920s excavation of his tomb, the mummy of King Tutankhamun was long said to be the source of a curse that left corpses in its wake, starting with the death of the dig’s sponsor. Lord Carnarvon died of a fever in Egypt, supposedly at the same moment that his dog died in England and around the same time that his pet bird met its maker courtesy of a snake. There were others, too, if the myth was to be believed, all dropping dead after their desecration of Tut’s tomb. There was no curse, of course, but the idea of King Tut cursing anyone who disturbs his body’s eternal slumber is the stuff of legend. Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat went looking for the source of the curse legend and found it in a pretty unlikely place—what he described as a sort of mummy striptease and stage show that was all the rage about 100 years before Howard Carter made his historic discovery. The show was all about unwrapping mummies on stage and before audiences, leading several authors to write some classic horror tales about the consequences of this admittedly weird trend. One of the most famous of these authors was Louisa May Alcott, better known for Little Women. Her “Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy’s Curse” told the story of an explorer who stole a gold box from the hands of a mummy before chucking her body in the fire. The box contained seeds from an unknown plant. Later, they translated a scroll that she had been buried with and learned that the mummy had been the body of a sorceress who’d cursed anyone who disturbed her body. The explorer and his betrothed decided to plant the seeds, and a white and scarlet flower bloomed . . . even as she grew sicker and sicker. Everyone connected to the seeds, the flower, and the mummy soon withered and died. Montserrat was certain that Alcott’s story was the source of the idea of the curses associated with mummies, but other Egyptologists aren’t sure. According to American University in Cairo Egyptologist Salima Ikram, some of the earliest mastabas in Egypt were inscribed with images of crocodiles, lions, and scorpions as a warning of the fate that awaited anyone who disturbed the remains. Read More: Twitter