Well, the twentieth century certainly wasn’t short on innovation—and it should come as no surprise that we’ve made a few decent attempts at flying cars over the years. Some were genius, others hilariously misguided, but they all add an extra little pinch of flavor to the legacy of our era. Here are ten amazing examples of flying cars from over the years.

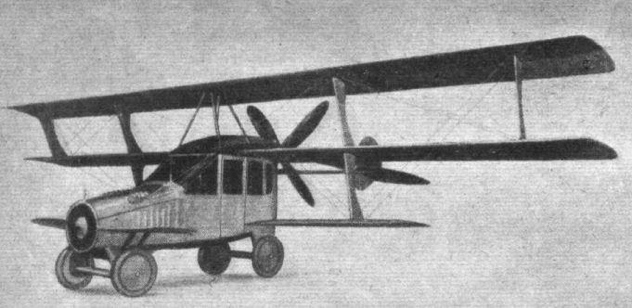

The Curtiss AutoPlane is pretty much the first glimpse the world got of a flying car, outside the pages of fiction. In 1917, an aviation engineer named Glenn Curtiss dissected one of his own airplane designs and slapped some of the pieces onto an aluminum Model T. The airplane it was based on was called the Curtiss Model L trainer, a triplane (three rows of wings) with a one-hundred-horsepower engine (which is about as powerful as a decent tractor). Like a car, the front two tires could be turned with a steering wheel inside the cabin, and it was propelled on the ground and in the air by a propeller attached to the back. Unfortunately, the “limousine of the air” never really flew—by all accounts, the most it could manage was a series of short hops before it was discontinued at the start of WWI.

This flying car is almost a legend, and besides this photo and a brief mention of the vehicle in a newspaper clipping from Andalusia, Alabama, it might as well have not existed at all. According to the story, the photo above is of Jess Dixon; it was supposedly taken sometime around 1940. Although it’s considered a flying car by aviation history buffs, the machine is actually closer to a “roadable helicopter,” due to the two overhead blades spinning in opposite directions. In other words, it’s a gyrocopter that can also roll. The Flying Auto was powered by a small forty-horsepower engine, and foot pedals controlled the tail vane on the back, allowing Mr. Dixon to turn in mid-air. It was also supposed to be able to reach speeds of up to one hundred miles per hour (160 kph), and was able to fly forwards, backwards, sideways, and hover. Not bad for a flying car that was never heard from again.

The Convair Model 116 Flying Car took flight for the first time in 1946, and looked like nothing more than a small airplane welded onto a car. And essentially, that’s exactly what it was. The wings, tail, and propeller could be detached from the (plastic) car, allowing it to be driven like a regular vehicle on the road. When it needed to go where no roads could take it, the plane attachment was fitted on. The 116 model only had one prototype, which itself managed a whopping sixty-six flights. A few years later, designer Ted Hall recreated the machine as the Convair Model 118, bumping the engine from a 130-horsepower model to a 190-horsepower beast that gave it more power in the air. Convair planned to build 160,000 for their first production run—but that never panned out, thanks to a tragedy which saw one of the prototypes crash in California. When the pilot took the car into the air, he had assumed that the fuel tank was full. But the ConvAirCar had two fuel gauges—one for the car’s engine and one for the plane’s—and while the car still had plenty of gas, the plane engine ran dry in mid-air. Such are the dangers of multi-tasking.

The Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 resulted from one of the first attempts by the US military to get involved in the flying car industry. Ideally, the VZ-7 was meant to be a type of flying jeep. Like a jeep, it allowed the pilot to maneuver through rough terrain on the ground—but with the not-insignificant bonus that it could also fly. It was developed by Curtiss-Wright, which, interestingly, formed through the merger of the Wright Company (the Wright Brothers) and Curtiss Aeroplane (Glenn Curtiss). Curtiss and the Wright Brothers had been fierce rivals during the early days of aviation. The VZ-7 was designed as a VTOL craft—Vertical Take-Off and Landing. It flew with the aid of four upright propellers, which were positioned behind the “cockpit,” more or less just an open-air seat. In order to maneuver, the pilot could change the speed of individual propellers, tilting the craft forwards, backwards, or to the side. Technical aspects aside, the entire thing was a death trap, since none of the propellers were covered—and in 1960, the army cancelled the project just two years after its commencement.

With the VZ-7 grounded forever, the army turned to a very different prototype: the Piasecki VZ-8 AirGeep. Bear in mind that helicopters had already become popular by this point; but it turned out that the military was interested in something smaller than helicopters, which could be successfully flown with less training. The AirGeep went through seven different versions before it was finally deemed “unfit for military use,” but they all kept the basic design: two large vertical propellers in the front and the back of the craft, with a seat in the middle for the pilot and either three or four wheels for ground use. While the first model was flat, later ones curved upwards at the front and back to form a flattened V-shape. The navy even tried to fit one model with floats, with the hope of using it at sea—but that idea was eventually abandoned, along with the rest of the program.

In 1971, the Advanced Vehicle Engineers company in California decided to design a flying car that was reminiscent of the ConvAirCar of the 1940s. They took a Ford Pinto, welded a Cessna Skymaster to the top, and essentially called it a day. The bizarre hybrid monster that resulted was dubbed the Ave Mizar. The car-half of the craft was fairly similar to any normal Ford Pinto on the street. The Pinto’s engine brought the plane up to speed for take off, at which point the plane’s propeller took over. Upon landing, the car’s brakes were responsible for slowing it down. Unfortunately, in 1973—just a year before the car was scheduled to begin mass production—the right wing of one prototype crumpled in mid-air. The car plummeted to the ground, taking any future it might have had with it.

As we broach the modern era, it’s surprising to see how far we still are from developing a practical flying car. Case in point: the Butterfly Super Sky Cycle, which doesn’t look much different to Jess Dixon’s fabled Flying Auto. Like the 1940s incarnation, the Super Sky Cycle is technically a road-able gyrocopter, with a single folding propeller and a swiveling tail to steer the craft in flight. The Super Sky Cycle was built in 2009 and is now (as of 2012) fully legal to drive, provided you have a motorcycle license and a pilot’s license. It even folds down to seven feet (2.1m), allowing it to fit into most garages. The gyrocopters are manufactured by Butterfly Aircraft LLC, and sold as kits that you assemble at home. It may not be what most people envision when they think of flying cars; regardless, they’re available to anyone with an spare $40,000.

In 2009, the Terrafugia Transition had its first successful test flight. Since then, it’s gone through a whirlwind of upgrades and remodels, resulting in several completely new designs and a second successful test flight in 2012. In any case, the Transition finally offers something that at least looks futuristic. It has the aerodynamic shape of a plane, with wings that fold in and then swivel into a vertical position while on the ground. It can reach up to seventy miles per hour (110 km/h) on the highway, and 115 miles per hour (185 km/h) in the air. One problem that the company faced in designing the Transition was that it was too heavy to comply with FAA regulations, due to all the extra parts needed to be safe on the road—such as bumpers and airbags, for instance. In 2010, the FAA decided to let the flying car slide through the regulations, which changes its classification and makes it easier to get the appropriate pilot’s license. Unfortunately, it still costs more than a Lamborghini.

Bringing some much needed style to the world of autogyros, the PAL-V One is a Dutch design, which makes some huge changes to the traditional format. For starters, it only has one engine; the power is automatically switched between the tires and the propeller, depending on whether or not it is making contact with the ground. What’s especially interesting about the PAL-V craft is that it’s only meant to fly below four thousand feet (1,200 m), which essentially means that you don’t have to file a flight plan to use it—a huge hurdle for flying cars in modern times. This could well lead to GPS-guided “digital corridors,” invisible highways in the sky that would allow airborne traffic to remain organized, like cars upon a regular highway.

The AirMule is more like an airborne ambulance than a car—but the idea is still the same. It’s being developed by the Israeli company Urban Aeronautics, and its main purpose would be assisting search and rescue missions. While it could feasibly reach the same speeds as a regular helicopter, it uses less than half the airspace, so it can also squeeze into areas that would be impossible for a helicopter. If you’ve been reading, you can probably tell that it looks a lot like the AirGeep designs the military tried to hatch in the 1970s. But it has one crucial difference: it’s flown remotely. That’s right, the AirMule is unmanned, which either means it’s going to be instrumental in saving lives, or—based on the way UAVs have been used in the past—taking them. Even so, it won’t necessarily be on autopilot—Urban Aero plans to use a remote pilot with flight controls and a bank of monitors to control the AirMule in real time—a little like the way we might control planes in a complex video game. Read More: Twitter Social Media HandleyNation