But perhaps their greatest achievements were in the area of mechanics. From the first computers to the first clock tower, the ancient Greeks built some truly amazing machines, some of which wouldn’t exist again for another 1,000 years. Some were practical, while others were simply for fun or to aid in scientific demonstrations. Let’s take a look at ten of the greatest examples of ancient Greek mechanical engineering.

10 The Antikythera Mechanism

The Antikythera Mechanism is an analog computer that was discovered in an ancient Greek shipwreck in 1901. Assembled sometime between 205 BC and 60 BC, it was designed to measure the movements of the heavens. It had a clock-like face with seven hands that tracked the movements of the planets and the Moon and also had mechanisms for tracking the phase of the Moon, the calendar, and the lunar and solar eclipses.[1] It turned our understanding of Greek engineering upside down when it was first properly identified in 2006, with its extremely precise and interlocking gear systems. It demonstrated that the ancient Greeks were capable of a level of precision engineering that was previously thought impossible. And it might not even be the oldest version of this machine—Cicero, the Roman writer, described Archimedes building a similar device in the third century BC. Unfortunately, only fragments of the device were recovered, so key features of it—such as how the device drove the planetary pointers, which no doubt must have been very complex, considering how the planets’ paths through the sky vary—are still not understood.

9 The Diolkos

The ancient Greek city of Corinth was a center of maritime trade in the ancient world, and it saw hundreds of vessels in its port at any one time. It was also close to the narrowest bit of land in the Greek peninsula, which would have saved ships days of travel if they could take a shortcut through it.[2] Hence the construction of the Diolkos sometime around the fifth century BC, a special kind of portage road that allowed ships to be hauled overland, avoiding the long trip around the Peloponnese. In the past, it used to be thought of as a way of transporting cargo ships quickly from the Aegean sea to the Ionian and vice versa, but it is now widely believed that cargo ships would have been too large to use the Diolkos, which would explain the construction of the Corinthian Canal in AD 67. Nonetheless, it probably played an important role as a cheap method of moving small ships and military vessels between the seas in a hurry and was probably used by wealthy Greeks with their own personal boats as a fast form of transport.

8 Philo’s Gimbal

The gimbal serves many purposes today—not least in the world of television, where its role in stabilizing handheld cameras keeps filming nice and smooth—but the very first gimbal was invented by Philo of Byzantium sometime around 200 BC, when he used it to make an inkwell that would never spill.[3] The ink was mounted in a container at the center of the device, surrounded by concentric circles that always held it upright, even when turned. The frame around the outside featured numerous holes to dip the pen into—so the writer could turn the inkwell over, or accidentally knock it, and still continue writing without spilling any ink. In later eras, the gimbal became absolutely crucial for navigation, holding a compass steady on a rocking ship so that the compass point always accurately pointed north.

7 The Kleroterion

The ancient Greek version of democracy may look primitive to our modern eyes, but they used a very innovative device to ensure that juries were always made up of people who couldn’t be bribed or otherwise influenced: a randomization machine.[4] A kleroterion was a kind of slot machine with some funnels, a crank, a hole, and 500 small slits. When a jury was assembled for a trial, each juror brought with them a form of ID—a thin piece of bronze or wood with their identifier on it, called a pinakion. These were all inserted into the slits. An officer tipped a handful of balls into the funnels at the top of the device—some black, some white. He then pulled the crank, causing one ball to come out. If the ball was black, the row of pinakia were removed, and those jurors wouldn’t serve that day. If the ball was white, those jurors were eligible for duty. The official pulled the crank for each row of pinakia until they’d all been accepted or rejected. There was no way to predict which ball would come out for which row, thereby ensuring that no one could have guessed before the trial who would be on the jury, preventing them from influencing their decisions.

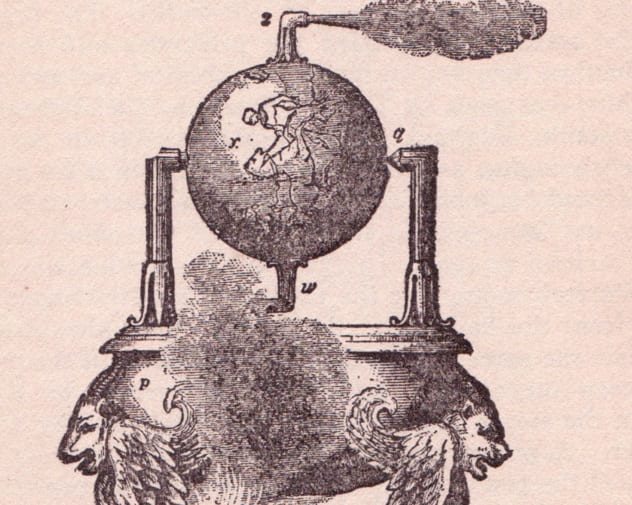

6 The Aeolipile

The aeolipile was, as far as we know, the world’s first steam engine—invented in the first century AD, roughly a millennium and a half before they became a common means of generating electricity. It was invented by Heron of Alexandria. However, it certainly wasn’t intended to be an engine, and Heron never saw it as such. Rather, he used it as a simple device to demonstrate some of the principles of pneumatics, no doubt to aid in lessons or to attract the attention of curious visitors. The engine itself was a hollow sphere mounted on two tubes it could rotate around. The tubes provided steam from a hot cauldron below the machine. As the steam filled the sphere, it escaped through another tube (sometimes two) that jutted out of the sphere. These tubes were angled sideways, so the force of the steam coming out caused the sphere to rotate.[5]

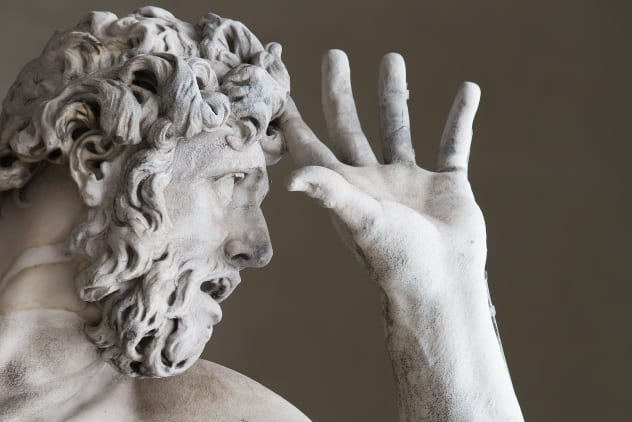

5 The Crane (And Archimedes’s Claw)

The Greeks invented the crane around the year 500 BC, a simple wooden hoist-and-pulley system that made erecting tall, sturdy buildings much more practical. (The technology was later improved by the Romans, who spread it across most of Europe.) However, the Greeks could easily build advanced cranes of their own, as is proven by Archimedes’s Claw. Archimedes’s Claw (depicted rather fancifully in the painting above) was a machine built in Syracuse by Archimedes sometime before the Roman siege of the city in 214 BC.[6] According to ancient accounts, the claw was a kind of crane that could either push or lift ships out of the sea, toppling them and causing them to sink. It was mounted close to the city’s sea walls, preventing Roman ships from coming close to the city. According to Plutarch, the claw terrified the besieging Romans, who began to feel like they were fighting against the gods, and many soldiers were frightened by the sight of any wooden frame above the city walls in case it was another one of Archimedes’s contraptions. They gave up any hope of taking the city by sea, resigning themselves to a long land-based siege.

4 The Tower Of The Winds

Built in roughly 50 BC, the Tower of the Winds in Athens is widely considered to be the world’s first meteorological station as well as the world’s first clock tower.[7] In ancient times, it was topped by a weather vane that indicated the direction of the wind. The tower has eight walls, each facing one of the compass points, and features a massive sundial which could be used to track the time of day. It had a water clock inside, which kept track of time overnight or on cloudy days. Its considerable height and its dominant position on the Roman Agora in the city both seem to suggest it was intended to function in much the same way as a clock tower would today, and the ancient Greeks themselves knew it as the Horologion: “Timepiece.” The building still stands today and is remarkably intact, mostly due to restoration work. It has inspired many architects over the course of history, and smaller replicas are scattered across Europe.

3 The Showers Of Pergamum

The ancient Greeks are famous today for their love of athletics, seen most prominently in the Olympics and their modern-day revival. What they are less known for, however, are the facilities ancient athletes sometimes enjoyed. A system of showers was excavated at a gymnasium (built in the early second century BC) in Pergamum, which was one of the greatest ancient Greek cities.[8] Now located in modern-day Turkey, it also hosted the greatest library outside of Alexandria, and its rulers consciously invested in the public works of their city to increase its prestige. As such, it is unlikely that these shower systems were common across the Greek world, but they certainly existed. The Pergamum showers had seven bathing units, into which water flowed through an overhead mains system onto the bathers. A shower system is also depicted on a vase from the fourth century BC, so by the time Pergamum’s showers were built, the ancient Greeks had been using showers for over a century. The image on the vase even depicts separate cubicles and rails for users to hang their belongings on.

2 Archimedes’s Screw

Archimedes is commonly considered to be the inventor of the Archimedes screw, a machine used even today for transporting water to a higher level with relatively little energy.[9] The ancient Greek version was powered by treading, where human workers or slaves would use their weight to power the machine—the crank-operated version was invented in medieval Germany. It is argued that Archimedes’s screw wasn’t the first such device to exist in the ancient world. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, built circa 600 BC, were said to have been watered by screws. However, the earliest source who says this is Strabo, writing almost 600 years later—and long after the invention of Archimedes’s screw, so he may have been using his knowledge of the technology around him to theorize how the Hanging Gardens might have worked. The site of the Gardens is still a mystery even today, so there is no way of knowing for sure. Even so, the machine didn’t become commonly used until Archimedes’s lifetime, when it started to be employed by the Greeks and, later, the Romans for irrigation or for draining ships.

1 Heron’s Fountain

Another device designed by Heron of Alexandria to demonstrate physics, Heron’s fountain used the principles of hydraulics and pneumatics to create a fountain that spurts water without power.[10] It is used even today in physics classrooms to aid teaching. Heron’s fountain is made of three components: an open bowl, an airtight water-filled container, and an airtight air-filled container, each stacked above the other. A pipe leads from the bottom of the bowl to the air container, another leads from the air container into the water container, and another leaves the water container and is positioned above the bowl. When water is poured into the bowl, it falls down the pipe into the air container. Pressure in the air container then pushes air into the water container, which pushes water up the pipe and back into the bowl, where it creates more pressure in the air container. While not physically practical, like Heron’s other devices it shows the incredible grasp the ancient Greeks had on physics over 1,000 years before the Renaissance and the scientific revolution. The device is not technically a perpetual motion machine, though it can run for a very long time if constructed to the right specifications. Resetting it is as simple as draining the water from the air container back into the water container.